- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

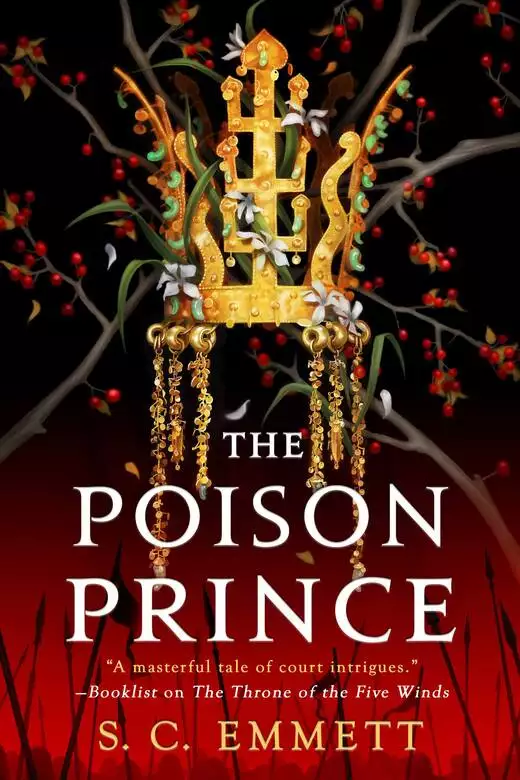

Synopsis

The lady-in-waiting to the princess of a conquered kingdom must navigate a treacherous imperial court, in the second book in a medieval East Asia-inspired epic fantasy trilogy. The crown princess has been assassinated, reigniting tensions between her native Khir and the great Zhaon empire. Now her lady-in-waiting, Komor Yala, is alone in a foreign court, a pawn for imperial schemes. To survive and avenge her princess, Yala will have to rely on unlikely allies -- the sly Third Prince and the war-hardened general who sacked her homeland. But as the Emperor lies upon his deathbed, the palace is more dangerous than ever before -- for there are six princes, and only one throne. Hostage of Empire The Throne of the Five Winds The Poison Prince

Release date: November 24, 2020

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 560

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Poison Prince

S.C. Emmett

The traditional crumbling mausoleum of historical petty princes and ambitious, likewise historical warlords was to the north of the city’s simmering, its borders hard pressed by ramshackle temporary dwellings spreading in that direction. The Emperor Garan Tamuron, however, had decreed a new, more auspicious site for the Garan dynasty just outside the walls facing the setting sun. His long-dead first wife’s urn was sealed in a restrained, costly tomb-wall, and any in Zhaon could have reasonably expected that another imperial wife or concubine would follow— or, in the worst case, the Emperor himself.

Instead, it was Garan Ashan Mahara, daughter of the Great Rider of Khir and new bride to the Crown Prince of Zhaon, whose restrained and beautifully carved eggstone urn was immured next to the Emperor’s memorialized spear-wife, and the interment had proceeded with almost unseemly haste but great pomp, honor, and expense.

It was considered wise to show a princess’s shade, as well as her home country, a certain respect.

Thunder lingered over distant hills as a slight woman in pale, well-stitched mourning robes of unbleached silk put her palms together and bowed thrice. A small broom to sweep the tomb’s narrow, sealed entrance and the dimensions of a Khir pailai was set aside in its proper alcove; the carved stone showing the name and titles of a new addition to the ranks of the honorable dead was marked first in Zhaon characters, then in Khir. Each symbol had the painfully sharp edges of fresh, grieving chisel-marks.

The mourner’s black hair held blue highlights and a single hairpin thrust into carefully coiled braids, the stick crowned with an irregular pebble wrapped with crimson silk thread. Neither ribbon nor string dangled small semiprecious beads or any other tiny bright adornment fetchingly from that pebble, for Khir-style mourning did not admit any excess.

At least, not in that particular direction.

Komor Yala’s chin dropped; her breath touched her folded hands. The hem of her pale silk overdress fluttered, fingered by a hot, unsteady breeze. It was almost the long dry time of summer, but still, in the afternoons, the storms menaced. The lightning was more often than not utterly dry as well, leaping from cloud to cloud instead of deigning to strike burgeoning earth. At least the harvest would be fine, or so the peasants remarked— softly, cautiously, in case Heaven overheard and took offense.

A bareheaded man in very fine leather half-armor waited at a respectful distance, his helm tucked at a precise angle under his left arm and a dragon-carved swordhilt peering balefully over his shoulder. He stayed motionless and patient, yet leashed tension vibrated in his broad shoulders and occasionally creaked in his boots when his weight shifted.

For all that, Zakkar Kai did not speak, and if it irked him to wait for a woman’s prayers he made no sign. The head general of Zhaon’s mighty armies had arrived straight from morning drill performed on wide white Palace paving-stones to accompany Crown Princess Mahara’s lone Khir lady-in-waiting outside the city walls, and his red-black topknot was slightly disarranged from both helm and exertion.

Finally, it could be put off no longer. Komor Yala finished her prayers, her lips moving slightly, and brushed at her damp cheeks. She had swept the pailai clean before Mahara’s wall, and gave another trio of bows. Her clear grey eyes, feverishly aglitter, held dark sleepless smudges underneath, and her cheekbones stood out in stark curves.

The Zhaon would say grief is eating her food; a Khir proverb ran a slight woman carries poverty instead of sons.

She backed from the tomb’s august presence, pausing to bow again; when she turned, she found Zakkar Kai regarding her thoughtfully, deep-set eyes gleaming and his mouth relaxed. He offered his armored right arm, still silent.

The absence of sweetened platitudes was one more thing to admire in the man. Her brother would have liked a fellow who could refrain from polluting a serious visit with idle chatter; a slow smolder of hidden unforgiving fire, that had been Komori Baiyan.

But her damoi was struck down at Three Rivers, where so many other noble Khir sons had fallen. Yala could not decide if he had likely faced Zakkar Kai upon that bloody field, or not. She also could not decide how to feel about either prospect. It was not likely Kai would speak of battle with a foreign court lady, even if he had noticed a particular Khir rider during the screaming morass of battle.

Yala placed her fingers in the crook of his right elbow; the general matched his steps to hers. Finally, he spoke, but only the same mannerly phrase he used every other time he accompanied her upon this errand. “Shall we halt for tea upon our return voyage, Lady Yala?”

“I am hardly dressed for it,” she murmured, as she did every time. Near the entrance to this white stone courtyard, in the shade of a long-armed fringeleaf tree with its powdery scented blossoms, her kaburei Anh leaned against the wall like a sleeping horse, leather-wrapped braids dangling past her round shoulders. “And your duties must be calling you, General.”

“They may call.” He never left his helm with his horse, as if he expected ambush even here; or perhaps it was merely a soldier’s habit to carry gear. “I am the one who decides the answer.”

A man could afford such small intransigence. Yala’s temples ached. She made this trip daily; it was not yet a full moon-cycle since her princess’s last ride. Yala herself had attended her princess’s dressing upon that last day, grateful to be free of the dungeons.

Had she still been imprisoned, or had she not avoided the shame of a flogging, would Mahara still be alive?

“And I am not dressed for such a visit,” Kai continued, levelly. “We make a strange pair.” He halted inside the fringeleaf’s shade as Anh yawned into alertness.

“Very.” Yala’s throat ached. The tears rose at inopportune moments, and she wondered why she had not wept for Bai so. The grief of her brother’s passage to the Great Fields was still a steady, silent, secret ache, but Mahara…oh, the sharp, piercing agony was approaching again, a silent house-feline stalking small vermin. Yala forced herself to breathe slowly, to keep her pace to a decorous glide, to keep her unsteady limbs in their proper attitudes.

“There is a cold-flask tied to my saddle,” Kai said almost sharply, his intonation proper for commanding a kaburei. “Our lady grows pale.”

“I am well enough,” Yala began, but Anh bowed and hurried off down the long colonnade. It would take her time to reach the horses, but her mistress and the general would still be in sight.

Zakkar Kai was careful of Yala’s reputation, though it mattered little now. With her princess reduced to ash and fragments of bone by a pyre’s breath, what did matter?

Nothing much. Except perhaps the small idea growing in Yala’s liver, a painful, pricking consciousness that her duty to Ashan Mahara was hardly done.

Zhaon’s great general fixed his gaze forward as if upon parade and set off for the horses, which meant Yala accompanied him at the mannerly pace of nobles retreating before the august dead. They walked silently through bars of sunlight and shade; Yala kept herself occupied with counting the columns, the numbers pushing away a black cloud seeking to fill her skull. When her escort halted between one step and the next, half-turning to face her with a sharp military click of his riding boots, she did not look at him, studying instead the closest carven pillar.

So much room, so much stone dragged step by step from so many quarries, so many carven edges; Zhaon was a country of wastage and luxury, even with their dead.

Kai’s gaze was a weight upon her profile. “Yala.”

“Kai.” Her hand dropped to her side, hung uselessly. What now? Was he about to observe that he could not after all accompany her here every morning? He had been silent well past the point of politeness, today.

“I must eventually ride to the North.” His jaw tightened; the breeze played with his topknot, teasing at strands pulled free by the morn’s activity. “The Emperor…”

No more need be said. “Of course,” she replied, colorlessly. Khir, hearing the news of a princess’s death, had reoccupied the border crossings and bridges; no wains of tribute had reached Zhaon from its conquered northern neighbor, and merchants both small and large were uneasy. The entire court of Zhaon was alive with rumor, from the lowest kaburei to the princes themselves; even the Emperor must hear the mutters upon his padded bench of a throne high above the common streets. “He is your lord.”

Obedience was due no matter how the heart ached, in both Khir and Zhaon.

“He is also my friend, and he is dying.” Kai did not glance over his shoulder to gauge who might be in earshot, but here among empty apartments meant for shades and incense, who would gossip?

“Yes.” There was no use in dissembling; the entire palace knew the Emperor’s nameless malady was fatal. The rai gave up its fruit for eating and next year’s crop, children died of fever or misadventure before their naming-days, men rode to war and women retreated to childbed; every street was paved with thousands of smaller deaths— insects, birds, beasts of burden, and cherished or useful pets.

Death had its bony fists wrapped about the world’s throat, and its grasp was final.

“I may speak to him before I leave, should I find opportunity.” Kai’s gaze, usually a jewelwing’s weightless brush, was unwonted heavy today. “But not unless you tell me plainly whether or not I may hope.”

What was there to hope for, with Mahara gone and unavenged to boot? Yala blinked, her gaze swinging in his direction. His features came into focus, swimming through the heavy water in her eyes. A single traitorous drop slipped free, tracing a cool phantom finger down her cheek.

She studied him afresh— long nose, deep eyes, the usual hint of a sardonic smile absent from full, almost cruel lips, mussed topknot. His half-armor was in the Zhaon style, meant to provide both freedom of movement and some small insurance against bolts or sharpened edges; it was stiffened leather and waxed cords, buckles and straps, any lack of ornamentation belied by the quality of the materials. The heat-haze of a male used to healthy exertion tinged with a breath of leather enfolded her without touching the chill streamlets coursing through her bones.

She had suspected he might require some manner of answer today. “Should I ask you to be plainer in turn?”

“I’ve been exceedingly plain.” A faint ghost of a smile touched one corner of his mouth, but he continued in a rush, cavalry with leveled weapons sweeping all before it. “I can offer you protection. I have estates; they are modest, but I could well and easily acquire more.” The wad of pounded rai in his throat, meant to keep a man from choking on truth or its cousin— what he must say to survive— bobbed as he swallowed. “And…there is much affection, Yala, upon my side. Even if I am loathsome to a Khir lady.”

Was that what held him back? She could not ask so plainly, even if he was paying her the high honor of directness. “Loathsome is not the term I would use, General Zakkar. Even if my Zhaon is somewhat halting.”

“Your Zhaon is very musical, my lady.” The compliment was accompanied by a slight grimace, as if he expected her to bridle at it. Faint amusement lit his dark gaze for a moment before vanishing into somberness. “Dare I ask what term you would?”

“Kind.” She thought for a moment; the complexity of her feelings demanded a balancing of one quality against another. “And deadly, when you see the need.”

After all, who had killed the first assassin she had seen in Zhaon? This man, and no other. It was perhaps unfair to wonder whether he might be induced to move against a later attacker, one who had so far escaped justice.

“Another strange pairing.” He did not look away, no surrender accepted or considered. “Yala, will you marry me?”

Finally, he had said it. She could now answer I am still in mourning, and be done. She could turn her shoulder and deliver the cut with the calm chill of a noblewoman well used to clothing a sharp edge in pretty syllables.

Instead, she watched his eyes, muddy like a half-Khir’s. Within a single generation of admixture the gaze lost its directness; some held that the pale grey of nobility ran through the great houses because the Blood Years had forced them to marry their own more than was quite wise. Zakkar Kai’s face was not sharp enough to be even quarter-Khir; he did not have mountain bones. Gossip spoke of some barbarian in his vanished bloodline, a common brat-foundling taken up by a warlord who became Emperor of this terrible, choking, luxurious land.

Barbarian or not, he was mighty among his fellows and measured in courtesy. His careful generalship— standing fast to bleed his enemy, breaking away to replenish his army and tire his foe with chasing— had broken the back of Khir’s resistance, and the victory at Three Rivers had brought her princess to perfumed, hot-cloying Zhaon as matrimonial sacrifice.

That Crown Prince Garan Takyeo had been kind to his foreign bride was beside the point. This country had swallowed Mahara and her lady-in-waiting whole, and now Yala, bereft, was a pebble in the conqueror’s guts.

Another traitorous tear struggled free and followed its elder sister’s path down her cheek. As Yala should have followed Mahara, had she not been gainsaid at the pyre.

Leather made a soft noise as Kai’s callused fingertips brushed the droplet away. It was the first time a man other than her own brother had touched her thus, and Komor Yala almost swayed.

His was the hand wielding that antique dragon-hilted sword, cutting down many of Khir’s finest sons. It was the same hand sending the sword’s point through an assassin in a darkened dry-garden upon a wedding-night, defending Yala. That he had thought her the new Crown Princess was irrelevant; it was also Zakkar Kai who had brought her back to the palace complex after tracking a clutch of conspiratorial kidnappers who had definitely mistaken Yala for her princess.

How could she possibly put each event onto scales and find their measure? She was no merchant daughter, bred for and used to weighing.

“If I were free to answer,” she said slowly, “I would marry you, Zakkar Kai.” There was little point in dissembling. He was not the worst fate for a Khir noblewoman trapped in a southron court, and she— oh, it was useless to deny it, she rather…liked him. The more he showed of the man behind his sword, the more she found him interesting and honorable, until she could not be sure her estimation of his actions was from their merit or her own feelings.

A high flush stood along his cheekbones, perhaps from morning drill or the heat. Surely it could not be a surfeit of affection for a foreign lady-in-waiting. “But you are not?”

“I must write to my father.” Was that why she continued to deflect a general’s interest? How could she even begin to brush the characters that would explain this? It was craven and ignoble to think that as Zakkar Kai’s foreign-born wife she would not have to face her father’s disappointment at both her failure and her weakness.

“Of course.” He nodded, a short decisive movement of a man well suited to command. “I will not speak to the Emperor until you have word.” His throat worked again, and he did not take his rough fingertips from her face. A strange heat, not at all like Zhaon’s sticky, hideously close summer, spilled from that touch down her aching neck, and somehow eased the terrible hole in her chest. “I will wait as long as I must.”

It was the warrior’s reply to the Moon Maiden. A smile crept to her lips, horrifying her. How could she feel even the barest desire to laugh or seek comfort, here in the house of the dead? “You are quite partial to Zhe Har, scholar-general.”

“Only some few of his works.” Kai still did not move, leaning over her to provide welcome shade, the rest of the world made hazy and insignificant by the mere fact of his presence.

Why had he not been born Khir? Of course, he would be dead at Three Rivers, or Komori Dasho might— as he had told his daughter once— have refused any suit for her hand. It did no good to wish for the past to change, or to ask uncaring Heaven for any comfort. A single noblewoman’s grieving was less than a speck of dust under the grinding of great cart-wheels as the world went upon its way.

He leaned forward still farther, and Yala felt a faint, dozing alarm.

But Zakkar Kai, the terror of Zhaon’s enemies, stern in war and moderate in counsel, merely pressed his lips to her damp forehead before straightening and stepping back, leaving her oddly bereft. “Come.” He offered his arm again. “We must see you home, my lady.”

Home. If her father sent word quickly enough, she could plead filial duty and escape northward. No doubt Crown Prince Takyeo would provide an escort to at least the border. She could be in Hai Komori’s dark, severe, familiar halls by the middle harvest, facing her lord father’s displeasure without the shield of distance, paper, or ink.

Komori Dasho would never be so ill-bred as to directly refer to her shame, but his silent disappointment would be that much harder to bear.

Yala bowed her head and once more took Zakkar Kai’s arm. Her skull was full of a rushing, whirling noise but she held grimly to her task, placing one foot before the other on bruising, sun-scorched stone.

She had been sent to protect her beautiful princess, and failed. All else was inconsequential. The world was a cruel summer-glaring dream, and she was lost within it.

The Jonwa, home to Zhaon’s Crown Prince and hung with the pale paper bubbles of mourning-lanterns, was not much cooler than outside despite its stone floors and high ceilings. The massive sculpture of paired snow-pards in the entrance hall glowed, mellow speckled stone rubbed to satin in a pool of sunlight robbed of heat by a succession of several mirrors. The pards’ flanks cast a somber reflection upon polished wooden flooring, but the statue’s twin heads, facing each other in eternal deadlock, were both shrouded with unbleached linen.

Crown Prince Garan Takyeo, the first in succession to rule mighty Zhaon, sat at his study’s great ironwood desk, staring blankly at an open book upon the ruthlessly organized surface. It was Cao Lung’s Green Book, holding much upon the subject of mourning, but its block-pressed characters would not stay in their orderly falling-rain lines, wandering as the reader’s attention did.

He had been staring at this particular page for some while.

There was a feline scratching at the door-post, and Third Prince Garan Takshin, in a Shan lord’s head-to-toe black except for the pale slash of a knotted mourning-band upon his left arm, stepped through. “It won’t change into an eggbird, no matter how long you look at it,” he said by way of greeting, his scars— one vanishing under his red-black hair, another pleating his top lip into a sneer despite any attempt at pleasantry or even ease— flushed with morning sunshine. He had no doubt been at morning drill, and though the rest of him was freshly bathed his topknot was slightly rumpled.

“At least we would have the eggs if it did.” Takyeo tried a smile, rubbing at his freshly clipped and oiled mustache and smallbeard. Perched upon this backless chair with his wounded leg stretched straight and wrapped in odorous, herb-smeared bandages, attaining a pleasant expression was a more difficult operation than he could quite believe. “And a bright good morning to you, too. Have you eaten?”

“At dawn. Which is why I came; it is well-nigh lunchtime, and none of your servants will brave this room to scold you into keeping your strength.” Takshin’s dark, leather-soled house-slippers whispered as he padded to the shelves of annals, treatises, and other spine-bound or rolled items necessary for a prince’s intellectual exercise. He affected to study a shelf with much interest; the gold hoop in his ear gave a single savage glitter. “I am hungry too, so bestir yourself, old man.”

A thin thread of amusement broke the shell of blank inattention Takyeo had spent the morning in. It was a relief. “You are like an old woman. Come and eat, come and eat.”

“We must look after your health.” Takshin imitated an elderly maiden-auntie’s quaver, accompanying it with a rude gesture often seen in the sinks of the Theater District or Zhaon-An’s teeming slums. Usually, it was deployed when a brothel-keeper had not been paid her portion, or a gambling criminal wished to denounce dice for working against him without quite accusing his opponent’s hand of sleight.

The juxtaposition wrung a weary laugh from Takyeo, who began arranging his robe and his leg for the task of rising. Zakkar Kai’s pet physician swore the wound would heal true, but not if the Crown Prince placed undue strain upon sliced, violated muscle and bruised bone.

It was to Honorable Physician Kihon Jiao that Takyeo owed his ability to stand at all. The arrow that had almost crushed his femur was a heavy, barbarous affair of northern make, but many in outlying Zhaon provinces menaced by horseback bandits also used such things. The assassin’s hiding place— a bramble-choked hedgerow just outside Zhaon-An on a road much used for pleasure-jaunts by prince and noble alike— held no clues, nothing more than a blurred shape in long summer-juicy grass where the man had taken his ease and a leaf-covered pile of droppings showing that he had frequented the spot, an adder lying in wait.

“Shall I steady your cane?” Takshin continued, solicitously enough to be sarcastic, and Takyeo waved an irritated hand.

“Stop fussing, or I shall tell the physician you have a cough.” His hand felt strange without the greenstone hurei denoting princely status, returned to its owner by Zakkar Kai with a lack of comment and tucked carefully in the sleeve-pocket of whatever robe Takyeo wore. Even after dropping the ring upon the floor of the throne room and stalking away, Takyeo could not quite slip the traces of responsibility.

Gossip said the Crown Prince had flung the heavy greenstone band with its deep sharp seal-carving at his lordly father; gossip was wrong, and yet for once in his life Garan Takyeo wished it was not.

“He won’t believe it; I am generally held to be too sour to take ill in summer.” Takshin turned his back upon the study, staring at the shelves again. “He sent another letter this morning, Ah-Yeo.” The childhood nickname, born of lisping younger siblings’ half-swallowed attempts to honorably name their elder, brushed along paper and leather spines, touched the carved ends of neatly stacked scrollcases of segmented babu.

“Mh.” Takyeo left the Green Book where it lay. After lunch, he would try again. It was merely a question of will, was it not? Like everything else. “Of course it was not a Red Letter.” Those imperial missives, with their giant scarlet cartouches, could not be turned away. The Crown Prince’s orders to his steward Keh were very specific— nothing from the Emperor but a Red Letter could be brought into Takyeo’s presence.

Inside the Jonwa, he was the ruler— at least until his father ordered succession differently. There was no point in even hoping for such a change, since it would not alter the underlying battlefield.

Nothing would.

“Of course.” Takshin ran a callused fingertip, scraped from near daily, always punishing practice with weighted wooden sword and blunted knife, along a shelf of classics, his head cocked slightly. “He expects you to submit, regardless.”

“He does.” Takyeo had submitted all his life. Be princely, their father always said. You are my heir, and must behave as such.

It was unexpectedly easy to refuse. Or, if not quite refuse, then to drag his half-lame heels and parry the expectations hung upon him from the cradle. Sometimes Takyeo wondered what his long-dead mother would say of all this, but the painting of her in the ever-lit shrine Garan Tamuron attended daily— as well as the portrait enclosed in his eldest son’s own household shrine— merely smiled emptily.

The age of miracles, of painted mothers finding their voices to chide husbands and errant descendants, was long over, if it had ever existed outside of tales told to gullible children. No intercession could be expected, especially when Garan Tamuron, Emperor of Zhaon and Heaven-blessed father of many sons, had decided upon a certain course.

Takyeo paid his respects to his mother’s portrait in the Jonwa’s shrine daily too, like any good son. Since the wedding, his foreign wife had too. She has a kind face, his wife had said of his long-dead, barely remembered mother, and added her own shy smile.

An entire morning spent seeking to avoid thinking upon his grief was wasted now, and the strange buzzing inside his bones mounted another notch. He was no closer to discovering the source of that maddening, unsteady feeling. There was nothing about it in any of the medical treatises he had read in the course of a princely education, and he did not think Kihon Jiao would consider it a symptom.

Takshin half-turned, not quite glancing aside to regard his eldest brother. It was an unexpected mercy; either of them could say what they wished, not having to scrutinize the other’s face for a reaction. “I am glad you will not,” he said, finally, in a level tone stripped of his usual sharp sarcasm. “’Tis high time he learned what it is to be balked, and by you, no less.”

“It is not disobedience.” Takyeo found his leg was not overly stiff; the silver-headed cane propped against his desk took his weight admirably. “Merely disinterest.”

“So I have pointed out, but I do not think he takes it as comfort.” Takshin’s smile was not gentle at all. He had been a prickly but soft-hearted child before his first trip to Shan, prone to flinging himself into battle to right every perceived wrong. Now he made no move to aid his eldest brother, a welcome change from everyone else’s flitting and fussing.

Takyeo suspected any attempt to thank his younger sibling for such forbearance would be met with either indifference or a snarl, so he made none. “He probably suspects you enjoy my recalcitrance.”

“He suspects correctly. I only wonder it took you this long.” But speaking of their august father was not Takshin’s sole purpose, and nor was baiting his brother to lunch, the gleam in his eye said. “Your housekeeper is beside herself. You have given some orders she does not think are quite wise.”

Lady Kue was not given to gossip, but she could hardly keep such preliminary arrangements from the notice of another member of the household. Takyeo took a tentative step, found his balance and leg both held, and wondered how long the mercy would last. “I doubt she says as much.”

“You are correct. Still, there is a proverb in Shan about a master’s foolish wishes, and I would wager she is muttering it today.” Takshin’s chin almost touched his shoulder, keeping his brother in peripheral vision. Still, he did not turn, his broad back exposed. It was, like all his poses, only partly disdain, and wholly a message. And now Takshin, choosing his own course as usual, arrived at the heart of his business with his eldest brother. “Do you truly intend to withdraw to the countryside?”

Perhaps he was the only one who could— or would— ask in such a manner. Even Kai did not mention the rumors, though he was patently aware and had probably guessed Takyeo’s departure date as well, though such information lingered only in the secret cavern of the Crown Prince’s head-meat as of yet. “My household has undergone some changes of late, Taktak.” Takyeo made certain his robe fell in its usual folds. Pale silk, both bleached and unbleached, strict mourning, though he could have chosen regular cloth and an armband three days after the pyre. A wife was not a parent, and yet he wished to mark the fact of her absence even more profoundly. “Surely you have noticed.”

“Very well, we shall retreat to a country villa to lick our wounds.” Takshin took no offense. His slight, ironclad smile stayed just the same, not stretching or diminishing by any fraction. “I’m certain Lady Yala could use a change of scenery as well.”

“No doubt.” Takyeo was equally certain that consideration weighed heavily in his brother’s scales. It was not quite clear whether Takshin was simply fond of the Khir lady-in-waiting, or if he harbored other designs. If it was the latter, it would be the first time he’d evinced any real interest in a court lady, and it was just like Takshin to choose a foreign one. “I have not asked her plans or preferences. When her mourning is done, perhaps we shall find an accommodation for her.”

It was, after all, the least a Crown Prince could do. His wife would have wished her friend safely placed.

“Perhaps.” Takshin did not rise to the bait, unwilling as always to show his true feelings— and have them used against him. But he did turn to face his eldest brother fully, and that was an encouraging sign. “Well, are you ready to hobble to table, Eldes

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...