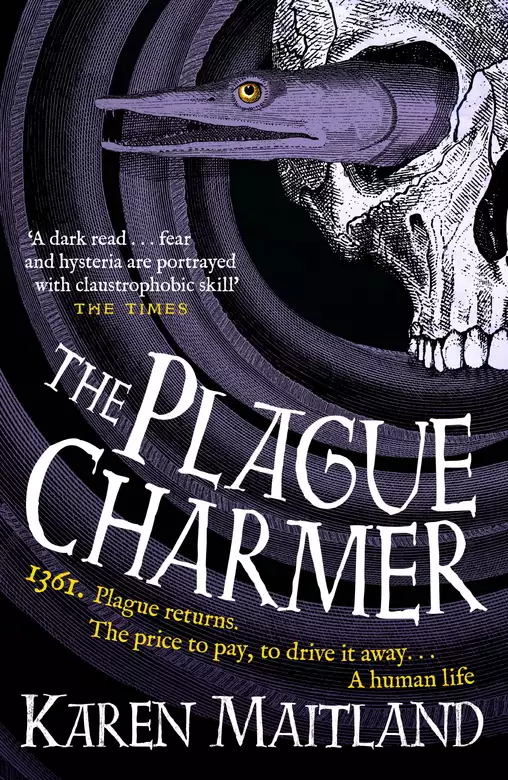

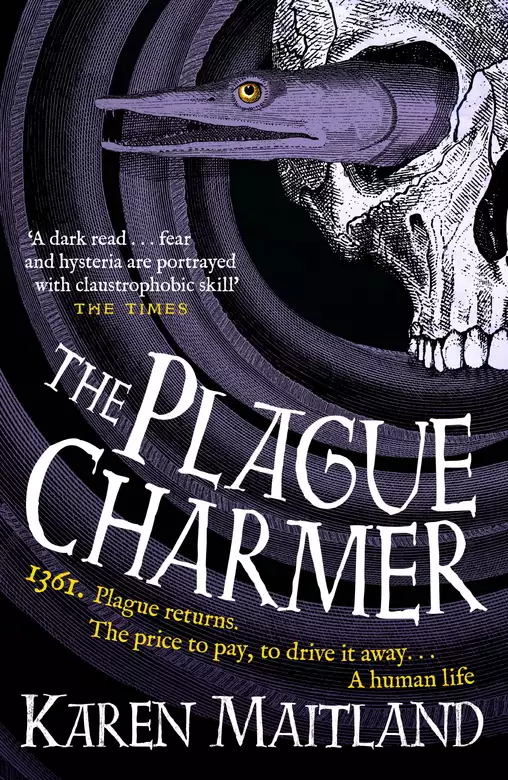

The Plague Charmer

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

The Plague Charmer, by Karen Maitland, author of the much-loved Company of Liars - her first novel of the plague - will chill and delight fans of Kate Mosse and C.J. Sansom in equal measure. 'A compelling blend of historical grit and supernatural twists' Daily Mail

Riddle me this: I have a price, but it cannot be paid in gold or silver.

1361. Porlock Weir, Exmoor. Thirteen years after the Great Pestilence, plague strikes England for the second time. Sara, a packhorse man's wife, remembers the horror all too well and fears for safety of her children.

Only a dark-haired stranger offers help, but at a price that no one will pay.

Fear gives way to hysteria in the village and, when the sickness spreads to her family, Sara finds herself locked away by neighbours she has trusted for years. And, as her husband - and then others - begin to die, the cost no longer seems so unthinkable.

The price that I ask, from one willing to pay... A human life.

Release date: October 20, 2016

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Plague Charmer

Karen Maitland

She appears without warning, standing in the mouth of the cave staring in at me. Tattered skirts and long strands of hair flap wildly in the sea wind, like the feathers of the dead gull washed up on the shore. Her face is in darkness. Her eyes glitter like a wild beast’s in the firelight. She stands there so long, so silently, that I think she may be the ghost of a drowned soul come to drag me down into the green waves below. I am not afraid. I would almost go willingly with her now. Almost, but not quite.

She crouches and from the depths of her cloak she pulls out a bundle, which she lays reverently on the rocky floor in front of my fire, an offering, as if I am a pagan god or Christian saint.

‘You will look after him? Keep him safe from them?’

The bundle stirs. A tiny fist clenches the air. The thing gives a faint mewing sound, like a cat demanding to be let in. I shuffle closer. The baby is naked, wrapped only in a goatskin. But not a cured skin: the inside is black with dried blood as if it has only just been ripped from the carcass, or perhaps it is stained with the woman’s birth blood. The infant looks to have been no longer in the world than the goat has been out of it.

‘Is the child sick?’ I ask her.

‘No . . . but he will be. They’ll make him sick . . . dead, like the others. I heard the owl. Owls know when death is coming.’ Her fingers pluck repeatedly at the rags of her skirt. She is crazed, poor creature, and little wonder.

‘Take it away. How do you expect me to care for it? What am I to feed it – mackerel?’ I drag myself backwards, deeper into the cave, making it plain I want nothing to do with the infant. ‘Even a grown man could freeze to death at night in this place – that’s if the sea doesn’t drown him first.’

‘But you’ll protect my baby. Creatures like you can keep us from evil spirits and make the sick well. I know it. I heard the stories. You’re a—’ She breaks off, as if even the name for creatures like me can conjure a power she dare not summon.

She’s wrong, though. A fraud is what I am, an imposter. They expect miracles of me, but they might as well stick bluebells up their arses and dance naked on the seashore for all the good it will do them. I am fool’s gold, though even now I do not admit it aloud.

The owls knew it was coming. The villagers knew it was coming. Even I knew it was coming. It was only a matter of time. But, you see, that’s exactly why it caught us unawares. It crept up on us and pulled our breeches down, cackling with laughter. Time is the tricksiest of all tricksters, and I should know. I was a jester by profession, but I never had the skills of Mistress Time. She can stretch herself into a shadow that reaches so far you think it’ll never come to an end or she can shrink to the shortest of mouse-tails.

You ask any man under sentence of execution, and I’ve seen a good many of those. I’ve mocked and pranced in front of them as they were hauled to the gallows. My lords and ladies have to be entertained while they wait for the main spectacle. Heaven forbid that time should drag for them. But for those piteous felons, desperately praying for more time, she races away from them. Yet the moment they fall to pleading for the pain and agony to be quickly over, Mistress Time wantonly slows to the pace of a hobbled horse. That is her way, the naughty harlot, to do exactly the opposite of whatever a man begs her to do.

The rumours of what was coming were brought by packhorse over the high moors, and ships that carried word to shore. It could not be ignored, should not have been ignored, but it was, even by me. Maybe we thought that there in that isolated village, with the steep hills protecting our backs and the raging sea as our ramparts in front, we were safe in an impregnable fortress. But when time lays siege to a castle, there is no fortress that she cannot take in the end.

I, above all, should have known the games Mistress Time plays. I was her creation or, rather, the creation of my master, who was in her pay. My master was proud of his handiwork, of me. You see, I am a nain, a dwarf. But I am not a natural dwarf, though you’d never guess to look at me. As my master constantly reminded me all the days I was growing up, or in my case not growing up, I am a sculpture, a carving, a work of art that took years of patient craftsmanship to perfect.

Not that I could ever disclose that to a living soul. My old master was paid a handsome purse for the purchase of a genuine dwarf, for they are valuable creatures. But it would’ve been my miserable carcass upon which my new lord would have vented his fury if he’d ever discovered he’d been cheated. You see, real dwarfs, natural-born dwarfs, are bringers of good luck. They protect the household from all kinds of evil and misfortune, like the relic of a saint or an amulet, only we dwarfs have more uses than simply to hang around on a wall. We can protect you from any sickness and cure any ailment. Just rub us on the affected part, like bear grease on to a bald pate, and see the miracle we can perform . . . which they can perform, but not me. I am a fake. I am the alchemist’s stone, which is nothing but a polished pebble, the finger of the holy saint, which is merely a dried chicken bone.

I watched my master create other dwarfs as he had made me and he was right: it requires rare talent and much time to create us little people. But I’ll tell you the secret, give it to you for nothing. Now that is a bargain you can’t refuse.

First you take a lusty infant – they must be strong to survive the moulding – and fit it with an iron frame over its baby head and face. One of the iron bars with hooks on either end goes in that little toothless mouth to stretch the lips into a permanent wide grin. Dwarfs are supposed to look cheerful, and it spares us the effort of having to fix our mouths into a grin in company. It wouldn’t do for that smile to slip, now, would it?

The other iron bars of the bridle flatten the baby’s button nose and squeeze its skull so that the forehead bulges with wisdom and intelligence. Next you must rub the infant spine daily with the fat of tiny creatures – shrews or dormice, bats or moles are thought to be most efficacious. Finally you strap the infant in its iron bridle into a snug, stout box, open at the front, of course, for you don’t want to suffocate your little homunculus – think of all that wasted time and money. Suckle it daily on the juices of dwarf elder, knotgrass and daisies mixed with milk from a dwarf goat. As the baby grows in its box, it will be compressed and deformed, squished and squashed ever tighter till it emerges from its mould, formed like a gingerbread manikin into the squat little dwarf that lords and ladies so desire.

My master was a kindly man, as he always reminded us whenever he beat us. It wrought his heart to hear the infants cry out with pain from the cramp and sores, and being so tender-hearted he could never bring himself to break their limbs to hasten the process, or dislocate their joints to make them bendy as acrobats. Dwarfs could be fashioned in a fraction of the time by such methods, he told me, though he never thought the results looked truly authentic. As a craftsman, he prided himself on the slow, careful moulding of the tender clay.

And when I was ready, fully baked so to speak, he sold me for a heavy purse to a sycophant who bought me as a gift for Sir Nigel Loring, the powerful envoy and confidant of Edward, the Black Prince, the hero of the battles of Crécy and Poitiers. As I was to discover, my new lord owned several manors, including Porlock, not that he ever spent much time at any of them, but my service for him proved to be the beginning of the journey, which, years later, was to end with me freezing my cods off in a damp sea cave only a few miles from that same manor at Porlock. As I say, Mistress Time plays some merry tricks.

I had been trained by my old master to be a jester – that is the job of the dwarf, to tumble and conjure, mock and mimic at feasts and festivals. But we do much more than that. We are also dispensers of punning wit that our lords fancy are words of profound truth, for we’re children with the faces of old men and out of the mouths of babes and sucklings, as the priests say.

Actually, I never minded that part so much. Those were the times I could make fools of the longshanks. All I had to do was turn a somersault, put on a droll face and declaim utter gibberish. The more nonsensical the words, the more attention they gave them.

‘I am the son of water, but when water touches me I die. Pray who am I, my lord?’

‘Let me think . . . I know this . . . Ice! The son of water is ice.’ Sir Nigel beams at the company triumphantly. His sycophantic guests applaud their host’s cleverness.

‘Aah, but the sun is a golden egg that none may eat, my lord. Beware the day water touches that sun for all will die.’ Now they nod as sagely as if I had just revealed a prophecy from St John himself.

You see, give them an easy one to make them think they’re clever, then you can babble complete drivel and get tossed a coin for it, because they would never admit before all the company that they cannot fathom the wisdom of a fool.

So innocently wise and so utterly truthful do the longshanks believe dwarfs to be that the fate of thrones and whole kingdoms is entrusted to the little people. Dwarfs are sent as gifts into the courts of rivals to act as spies. They’re entrusted to carry the secret documents of kings and traitors alike. They stand in plain view while their masters and attendants are searched, for who remembers to search the grinning child-fool? Dwarfs are sent out alone on battlegrounds, carrying the white flag with its offer of parley. They are trusted to approach even by the most wary, though we might wear the assassin’s knife: none can believe we could reach up to strike the victim’s heart.

But I never reached the battlefield, which would have granted me at least a little honour and glory. No, I was used as a bed-warmer to heat the feather mattress of Sir Nigel and Lady Margaret before they retired, so that they should not endure the shock of slipping naked between cold sheets. In winter, I was also foot-warmer to Lady Margaret’s mother when she was being carried in a litter between two horses. I crouched beneath the old woman’s skirts – her own lapdog, intended for the purpose, would not stop bounding from side to side across her lap, barking at every hound that was running alongside the riders.

When the old woman wanted to relieve herself on the journey, she’d rest her pisspot on my back. It was, as she said, a convenient height. But the indignity of that was nothing. After all, a jester loses his dignity so many times a day, he wouldn’t recognise it if he fell over it. No, the task I really hated was kiss-bearer.

It was the fashion then that when a woman wished to flirt with a man who was not her husband, she would seize a dwarf and smother him with wet kisses, then bid him deliver them to the object of her affections. The dwarf was supposed to climb upon the man’s knee and bestow on him the kisses he had received. Worse still, if the man was of a mind to return her advances, the longshanks would kiss the dwarf as many times as he desired to kiss the maiden or married woman and send the little person back to deliver them. As you can imagine, this mummery could continue for hours until the dwarf was as wet as if he’d been slobbered over by a pack of hounds.

That was not the worst of it. Sometimes this flirtation by proxy – or should I call it dwoxy? – went well beyond mere kissing. Every disgusting touch, each illicit fondling by both parties had to be endured by the dwarf, then re-enacted by him on the lover for whom it was intended. Inevitably the most enthusiastic players of this game were men and matrons of advancing years and foul breath. They trusted dwarfs, you see, for we always carried the truth. Poor fools, they never suspected that I was not a real dwarf. If one man in particular had known, he would never have entrusted me with the kiss that would shatter both my life and hers. It was a curse, not a kiss, I carried.

I turn around and the woman is gone, vanished as if a wave has licked her up out of the cave’s mouth and the sea has swallowed her. But the baby still lies where she left him, mewing resentfully and staring up at the roof of the cave where firelight and shadows dance out a thousand stories. I waddle over and scoop him up. I should toss him into the sea. It would be kinder. A few moments and it would be over. No pain, no fear, no agonising death that lasts too long and yet is far, far too short.

Instead, I find myself tearing my only spare shirt into strips to make swaddling bands. If you don’t bind those pliable limbs straight, the infant will grow bandy, not as bandy as me, of course, but if this baby must grow, let it be into a man, not a manikin. That much at least even a fake dwarf can manage.

I carry him to the cave entrance and stare out into the darkness. The waves foam white, rearing up and crashing down on to the pebble beach as if they mean to smash every stone to sand. Clouds race across the moon, like herds of animals fleeing some nameless predator. There is a storm coming, a storm greater even than the last one that brought so much destruction. I do not need the owls or even the gulls to tell me that. A storm was how it all began; maybe another will finish it. Finish it for us all.

The herring shoals are ruled by a royal herring, a fish which is of uncommon size. If this fish is harmed, the shoals will vanish and come no more to the shore.

‘The sea’s gone, Mam. Come and look!’ Little Hob’s shrill voice cut through the morning air, like the screech of a gull.

‘Tide’s always going out,’ I snapped. ‘Does it twice a day, boy, you know that.’

I’d no patience with his games that morning. The fire wouldn’t draw. It smouldered, sulky as a witch in irons, and the fish stew in the pot hanging above it was barely warm. There was no knowing when my husband would come down from the high moor with the packhorses, but when he did, he’d be ravenous and I’d have nothing to give him, save raw cod. Kneeling on the beaten-earth floor of our cottage, I thrust kindling sticks into the embers and tried to blow them into a blaze.

‘Haven’t you fetched the water yet, Hob?’ I called through the open door. ‘I told you to go at first light. And carry it carefully, mind. Don’t spill it.’

The spring near the cottage was usually gushing out of the hillside this time of year, but these past few weeks it had been just trickling down the rocks as if it was already late summer. My granddam told me that whenever the spring ran dry, it was because there was a great toad squatting in a cave deep inside the hill sucking up the water, and the only way to get it to move was to offer it gold. That toad would be sucking water for a long time afore it got any gold from me. I’d not a coin in the cottage, nor would I have till Elis came down from the moors.

‘Mam! Come and look now!’

My head was aching and Hob’s shriek went through it like a blade. Why do boys have to shout every word they utter, as if they’re yelling over a howling storm?

‘Sea’s really gone, Mam! I swear!’

‘Giss on!’ Luke, my eldest son, bellowed scornfully. ‘Last week you reckoned you’d seen a mermaid by the cliffs and it was nothing but a seal. Then you came running home, wailing like that old sour-face Matilda, saying a great brown bear chased you in the forest. Some bear! It was that mangy pedlar in his tattered old cloak, is all. Nug-head!’

‘You’re the nug-head for not coming to look,’ Hob taunted. ‘You’ll be sorry when everyone else has seen it and you’ve not.’

From the clatter of wood I guessed Luke had thrown down the load he was carrying. He flashed past the door, chasing after his brother.

‘Come back! There’s work to be done. If you don’t come here right now, I’ll send you both to Kitnor to live with the ghosts and witches.’

I don’t know why I wasted my breath. Once those two took off they’d only return when their bellies reminded them they were hungry. The one person Luke paid any heed to was his father, and not always then unless he saw Elis reach for the whip. I rocked back on my heels, rubbing my throbbing temples. The fire was at least stirring itself now, but if I didn’t put a log on the flames, it would soon die down again. Sighing, I heaved myself to my feet to fetch the wood Luke was supposed to be bringing in.

But as soon as I stepped outside, I knew something was wrong. It took a few moments before I could reason what was making me uneasy. Three hobbled mares stood in the small clearing just above me on the hillside, their bellies round as barrels, swollen with unborn foals. The morning was fine and sunny, yet they were not nibbling the tender spring grass. They were pressed hard against each other, their ears pricked, rolling their eyes and tossing their heads as if they could sense a wolf creeping towards them. I glanced fearfully at the dense mass of trees that rose up the steep hillside behind the cottage, but the horses were not looking towards the forest. They were turning their heads in every direction as if they couldn’t tell where danger threatened, only that they sensed it was coming.

Something else was wrong too. The bees! There was usually a steady trail of them flying between the flowers on the currant bushes and the skeps, but I couldn’t see a single one on the white flowers. My hand flew to my mouth. Blessed Virgin, surely we hadn’t lost them too! With our crops withering from lack of rain before they were even grown, we’d be sorely in need of all the honey the bees could make.

I ran towards the low stone wall in which the skeps were set to give them shelter from the sea wind. As I drew near I could hear a low, irritated humming coming from inside each one. I breathed deeply, muttering a prayer of thanks. They were alive, but why weren’t they flying? Something was amiss.

Our cottage sat in a dip, partway up the hill above the village, protected from the worst of the winter winds by a tree-covered rise in front and the broad back of the hill behind. I hurried down the stony track that led round the curve of the rise, until I reached the place where I could look down at the pebbly beach.

The sea had not vanished, as my son had sworn, but I could see at once what had so excited him. For the tide had ebbed out much further than usual, further than he had ever seen it in the seven years of his life. Even I’d seen it retreat as far only a few times, and then always on Lady Day or Michaelmas, when the incoming tides were at the highest, never at this season.

A small crowd of villagers was standing on the wooden jetty, but more swarmed over the mud flats. Out in the bay, far beyond the long stone walls of the fish weirs, I could just make out tiny figures, bending to gather something, perhaps stranded fish or crabs from the exposed seabed, though they were too far away for me to make out what they were collecting.

From their height and the way they moved, I could see that some of the villagers furthest out were just children. It was not safe for them to wander so far on that mud. Even the normal low tide exposed patches of quicksand beyond the fish weirs that could suck down a horse, and if the sea rolled back in along the channels, no one could outrun it, not in that ooze. What were their mothers thinking to let their young ones venture so far? A sudden chill gripped me. Hob! Luke! Where were they? I anxiously scanned the crowd on the jetty and the beach, but I couldn’t see any sign of them.

Picking up my skirts, I ran down the path, past the small stone cottages and the wooden smoke huts, towards the shore. As I ran, I stared wildly round at the groups of villagers, desperate to see the faces of Hob and Luke among them. I stumbled down on to the beach, wobbling on the broad pebbles, and picked my way over to where my sister-in-law, Aldith, stood, her baby son balanced on her hip, her little girl grasped tightly by the hand.

‘Aldith, you seen the chillern?’

Whenever Luke was missing or in mischief, I could always count on him being with her eldest son, Col.

‘Col’s with his father picking fish from the weir pool. He wanted to go far out in the bay with Luke and the other lads, but his father’s more sense than to let him. Couldn’t stop your Luke, though. He’s way out there.’ She turned to look at me, her eyes creased with anxiety. ‘If he were mine, Sara, I’d fetch him back straightway. When the tide goes out so far, she’ll surge back in like horses at the gallop and if your boy gets his feet stuck fast in that mud . . .’

Aldith didn’t need to finish her warning. Even strapping men could find themselves held tight in that ooze and drowned by the incoming tide.

‘Luke! Luke!’ I shouted. ‘Come back here at once!’

None of the figures in the far distance turned or made any move towards the shore. But if Luke had heard me, he’d ignore me anyway. He always did whatever he wanted and refused to think about the consequences, even a thrashing, till he had to face it. But this was far more serious than slipping away to go egging with his friends when he should have been hoeing the weeds.

Aldith gave me a sympathetic glance, still holding tight to her wriggling daughter. ‘He’d take notice if his father shouted for him.’

‘Elis took the widgebeasts over the moors yesterday. Could be sundown afore he returns, tomorrow even.’ I dragged off my shoes. ‘My Hob, is he out there too?’

Aldith jerked her head back towards the quayside. ‘Tried to follow Luke out, but Matilda grabbed him. Last I saw, she was telling him the devil would come for him in the night and drag him down to Hell if he didn’t repent his sins.’

That bitterweed, Matilda, would terrify the wits out of the boy with her spiteful sermons, but for once I was grateful to her. At least she’d keep Hob safely away from the sea. I hurried down to where the shingle beach gave way to wet, muddy sand, rocks and weed.

I glanced up. I could have sworn it was growing darker, though it was not yet noon, and the wind was rising, changing direction too. Was there a storm brewing? I searched the sky to see which way the gulls were flying. If they were heading inland, it would be a sure sign of bad weather. But there was not a single gull to be seen. On any other day the air above would be full of their screeching, but I realised I couldn’t hear the cry of any bird. I shivered, but not from the wind.

Holding my skirts above my knees, I ran down across the wet mud. Behind me, Aldith called something, but I couldn’t make out the words. I was too busy shouting for Luke. I picked my way round the outside of the thick stone walls of the nearest weir. The pebbles underfoot were slimed with bright-green weed and several times I had to grab for the wall to stop myself slipping.

The stones gave way to cold mud again, numbing the feet. It wasn’t until I felt the sharp salt sting and saw the scarlet blood running from beneath my instep that I realised I must have slashed it on a razor shell or a fragment of old iron stuck in the mud. At least I hadn’t trodden on a viperfish. Their poison made grown men weep in agony.

I squelched forward, shouting for Luke all the while, but I dared not lift my eyes to search for him as I picked my way between the sharp rocks.

Painful though it was, I tried to walk only on the patches of sharp stones or glistening swathes of bladder wrack, for though the smooth stretches of wet silt looked so soft and inviting, I knew they could conceal those viperfish or, worse still, might be quicksand from which there was no escape.

I paused and glanced up to get my bearings. Five boys were out ahead of me. I could see Luke now, furthest away from the others. There were shouts from the beach. I couldn’t catch the words, but some of the boys heard them and lifted their heads. Two began to wade back towards the shore. But Luke, oblivious to all, was crouching down and digging with his hands in the mud, trying to pull something free.

The sky was definitely growing darker, I was sure of that now, a strange half-light that leached the colour from land and sea, turning all to grey. I glanced up, expecting to see thick, black clouds, but there were only a few skeins of white on the horizon, no sign of any storm. Yet it was growing colder. The wind blew strange, whirling eddies across the pools of water trapped in the hollows of the rock and sand. The ripples were turning widdershins, against the sun. I knew it for an evil omen.

‘Hurry,’ I yelled at the nearest boys, waving my arms. ‘Get back to the shore now! Quickly!’

The boys looked alarmed, but they moved swiftly, or as swiftly as they could, weighed down by baskets of crabs, flapping fish and dripping slime-covered treasures, which might have been anything from broken swords to sea-sculpted driftwood.

Finally, Luke raised his head and stared at me, startled, as if he couldn’t understand what I was doing there.

‘Leave it, Luke. We must get back to the shore, there’s a storm coming.’

He squinted up at the wisps of white cloud in disbelief and waved a muddy hand at me. ‘I’ve almost got it, Mam, just have to dig a bit more.’

‘No, Luke, you have to come now.’

Why was it growing so dark? I glanced at the sky again. For a moment I thought a giant leech was crawling across the edge of the sun. Blinded by the dazzle, I rubbed my eyes and, squinting, tried to look up again. Blackness was oozing across the bright disc, obliterating the light as if the sun was slowly being swallowed by its own evil shadow.

‘Luke!’ I yelled, floundering towards him.

His head jerked up again and he suddenly seemed to notice that daylight had turned to twilight. As he straightened up, I saw that he was holding something covered with mud, but I didn’t stop to wonder what it was. My son waded towards me, his eyes wide with fear. I pulled him into my arms and hugged him fiercely, staring around. Luke clung to me. It was growing darker and colder with every panting breath we took.

‘What’s happening, Mam? The sun . . . is it gone?’

For one terrible moment, I didn’t know which way I was facing – towards the safety of the shore or the treacherous sea. Even on a moonless night the fishermen say they can still see Porlock Weir from the sea by the candles glimmering through the windows of the cottages and the fires in the yards glowing red. But it was noon and no lantern burned to guide our way back to the shore.

The sky, the earth, the sea had melted into one formless black mass. No birds cried above us. No animals called from the hill. The only sound was the desolate moan of the wind. It was as if we were ghosts wandering through the dark, icy caverns of the dead.

Then I heard a cry. I couldn’t make out the words, but knew it was human. I prayed it was coming from the shore. Grasping at the sound, as if at a rope thrown to guide me, I held Luke tight against me and urged him forward. We slipped on seaweed and grazed our legs on the shell-covered rocks. I heard Luke gasp at the pain, but I wouldn’t let him stop. Day had turned to night yet there was an eerie bone-white glow above us, like the ghosts of drowned sailors risen from the depths of the sea. I was afraid to look up, but I couldn’t help myself. The sun had turned as dark as a pool of tar. It hung as a black disc in the sky, with only a halo of a deathly cold flame snaking about it, like ice burning.

By then I scarcely knew if Luke was pulling me or I was dragging him. My legs were aching from the effort of trying to hurry through the cloying mud.

The voice drifted out towards us, pulling us to the shore. Domini venit crudelis . . . plenus et irae furorisque . . . peccatores eius conterendos de ea . . .

I could tell they were words now, though they made no sense to me, but I knew it for the same tongue as the priest used when he spoke the words of the Mass. But Father Cuthbert’s tone was dull and flat, like the beat of the flail when we threshed the corn in the barn. This was a woman’s voice, harsh and accusing as the skeins of greylag geese that cry, Winter, winter, as they fly. I glanced behind me, thinking to see a flock of angels screeching through the darkened sky, calling out that the Day of Judgment had come.

I thought I would trudge through that endless wasteland of mud and darkness for eternity. Then without warning my feet were scrabbling over shingle and I felt hands reaching out, tugging me up on to the track above the beach. I stood trembling, clutching Luke. I could feel him shivering and for the first time in many months he did not pull away from me.

A huddle of villagers silently faced the sea, only their clothes and hair moving in the wind. No one spoke. They just stared out into the strange twilight.

‘Behold, the day of the Lord is coming, a cruel day of wrath, and fury, to lay the land desolate, and to destroy the sinners. For the stars of Heaven shall not display their light: the sun shall be darkened in his rising . . .’ The woman’s voice rang out. ‘It is a warning. The prophecy of Isaiah has come to pass this very day. Fall to your knees and pray for forgiveness, pray that you may be spared!’

I could dimly make out a figur

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...