The thing I remember most

The thing I remember most--the thing I still have nightmares about--is when it was all but over.

I remember the roar of the wind as I stepped onto the terrace. It blew off the ocean in howling gusts that scraped over the cliff before slamming directly into me. Rocked onto my heels, I felt like I was being shoved by an invisible, immovable crowd back toward the mansion.

The last place I wanted to be.

With a grunt, I regained my footing and started to make my way across the terrace, which was slick from rainfall. It was pouring, the raindrops so cold that each one felt like a needle prick. Very quickly I found myself snapped out of the daze I’d been in. Suddenly alert, I began to notice things.

My nightgown, stained red.

My hands, warm and sticky with blood.

The knife, still in my grip.

It, too, had been bloody but was now quickly being cleaned by the cold rain.

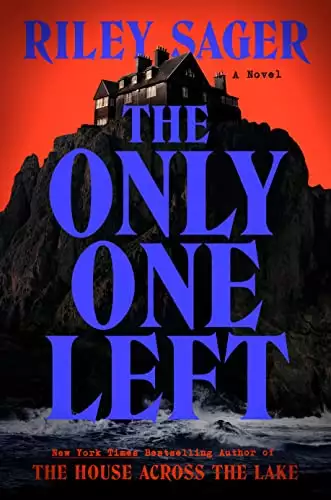

I kept pushing through the wind that pushed back, gasping at each sharp drop of rain. In front of me was the ocean, whipped into a frenzy by the storm, its waves smashing against the cliff base fifty feet below. Only the squat marble railing running the length of the terrace separated me from the dark chasm of the sea.

When I reached the railing, I made a crazed, strange, strangled sound. Half laugh, half sob.

The life I’d had mere hours ago was now gone forever.

As were my parents.

Yet at that moment, leaning against the terrace railing with the knife in my hand, the rough wind on my face, and the frigid rain pummeling my blood-soaked body, I only felt relief. I knew I would soon be free of everything.

I turned back toward the mansion. Every window in every room was lit. As ablaze as the candles that had graced my tiered birthday cake eight months earlier. It looked pretty lit up like that. Elegant. All that money glistening behind immaculate panes of glass.

But I knew that looks could be deceiving.

And that even prisons could appear lovely if lit the right way.

Inside, my sister screamed. Horrified cries that rose and fell like a siren. The kind of screams you hear when something absolutely terrible has happened.

Which it had.

I looked down at the knife, still clenched in my hand and now clean as a whistle. I knew I could use it again. One last slice. One final stab.

I couldn’t bring myself to do it. Instead, I tossed the knife over the railing and watched it disappear into the crashing waves far below.

As my sister continued to scream, I left the terrace and went to the garage to fetch some rope.

That’s my memory--and what I was dreaming about when I woke you. I got so scared because it felt like it was happening all over again.

But that’s not what you’re most curious about, is it?

You want to know if I’m as evil as everyone says I am.

The answer is no.

And yes.

ONE

The office is on Main Street, tucked between a beauty parlor and a storefront that, in hindsight, feels prophetic. When I was here for my initial job interview, it was a travel agency, with posters in the window suggesting freedom, escape, sunny skies. On my last visit, when I was told I was being suspended, it was vacant and dark. Now, six months later, it’s an aerobics studio, and I have no idea what that might portend.

Inside the office, Mr. Gurlain waits for me behind a desk at the far end of a space clearly meant for retail. Free of shelves, cash registers, and product displays, the place is too vast and empty for an office staffed by only one person. The sound of the door closing behind me echoes through the empty space, unnaturally loud.

“Kit, hello,” Mr. Gurlain says, sounding far friendlier than he did during my last visit. “So good to see you again.”

“Likewise,” I lie. I’ve never felt comfortable around Mr. Gurlain. Thin, tall, and just a bit hawkish, he could very well pass for a funeral home director. Fitting, seeing how that’s usually the next stop for most of those in the agency’s care.

Gurlain Home Health Aides specializes in long-term, live-in care—one of the only agencies in Maine to do so. The office walls bear posters of smiling nurses, even though, like me, most of the agency’s staff can’t legally claim the title of one.

“You’re a caregiver now,” Mr. Gurlain had told me during that fateful first visit. “You don’t nurse. You care.”

The current roster of caregivers is listed on a bulletin board behind Mr. Gurlain’s desk, showing who’s available and who’s currently with a patient. My name was once among them, always unavailable, always taking care of someone. I’d been proud of that. Whenever I was asked what I did for a living, I summoned my best Mr. Gurlain impression and replied, “I’m a caregiver.” It sounded noble. Worthy of admiration. People looked at me with more respect after I said it, making me think I’d at last found a purpose. Bright but no one’s idea of a good student, I’d eked my way through high school and, after graduation, struggled with what to do with my life.

“You’re good with people,” my mother said after I’d been fired from an office typing pool. “Maybe nursing is something you could do.”

But being a nurse required more schooling.

So I became the next best thing.

Until I did the wrong thing.

Now I’m here, feeling anxious, prickly, and tired. So very tired.

“How are you, Kit?” Mr. Gurlain says. “Relaxed and refreshed, I hope. There’s nothing better for the spirit than enjoying some time off.”

I honestly have no idea how to respond. Do I feel relaxed after being suspended without pay six months ago? Is it refreshing being forced to sleep in my childhood bedroom and tiptoe around my silent, seething father, whose disappointment colors our every interaction? Did I enjoy being investigated by the agency, the state’s Department of Health and Human Services, the police? The answer to all of it is no.

Rather than admit any of that to Mr. Gurlain, I simply say, “Yes.”

“Wonderful,” he replies. “Now all that unpleasantness is behind us, and it’s time for a fresh start.”

I bristle. Unpleasantness. As if it was all just a slight misunderstanding. The truth is that I’d spent twelve years with the agency. I took pride in my work. I was good at what I did. I cared. Yet the moment something went wrong, Mr. Gurlain instantly treated me like a criminal. Even though I’ve been cleared of any wrongdoing and allowed to work again, the whole ordeal has left me furious and bitter. Especially toward Mr. Gurlain.

It wasn’t my plan to return to the agency. But my search for new employment has been a total bust. I’ve filled out dozens of applications for jobs I didn’t want but was crushed anyway when I never got called in for an interview. Stocking shelves at a supermarket. Manning the cash register at a drugstore. Flipping burgers at that new McDonald’s with the playground out by the highway. Right now, Gurlain Home Health Aides is my only option. And even though I hate Mr. Gurlain, I hate being unemployed more.

“You have a new assignment for me?” I say, trying to make this as quick as possible.

“I do,” Mr. Gurlain says. “The patient suffered a series of strokes many years ago and requires constant care. She had a full-time nurse—a private one—who departed quite suddenly.”

“Constant care. That means—”

“That you would be required to live with her, yes.”

I nod to hide my surprise. I thought Mr. Gurlain would keep me close for my first assignment back, giving me one of those nine-to-five, spend-a-day-with-an-old-person jobs the agency sometimes offers at a discount to locals. But this sounds like a real assignment.

“Room and board will be provided, of course,” Mr. Gurlain continues. “But you’d be on call twenty-four hours a day. Any time off you need will have to be worked out between you and the patient. Are you interested?”

Of course I’m interested. But a hundred different questions keep me from instantly saying yes. I begin with a simple but important one.

“When would the job start?”

“Immediately. As for how long you’d be there, well, if your performance is satisfactory, I see no reason why you wouldn’t be kept on until you’re no longer needed.”

Until the patient dies, in other words. The cruel reality about being an at-home caregiver is that the job is always temporary.

“Where is it located?” I ask, hoping it’s in a far-flung area of the state. The further, the better.

“Outside of town,” Mr. Gurlain says, dashing those hopes. They’re revived a second later, when he adds, “On the Cliffs.”

The Cliffs. Only ridiculously rich people live there, ensconced in massive houses atop rocky bluffs that overlook the ocean. I sit with my hands clenched in my lap, fingernails digging into my palms. This is unexpected. A chance to instantly trade the dingy ranch home where I grew up for a house on the Cliffs? It all seems too good to be true. Which must be the case. No one quits a job like that unless there’s a problem.

“Why did the previous nurse leave?”

“I have no idea,” Mr. Gurlain says. “All I was told is that finding a suitable replacement has been a problem.”

“Is the patient . . .” I pause. I can’t say difficult, even though it’s the word I most want to use. “In need of specialized care?”

“I don’t think the trouble is her condition, as delicate as it might be,” Mr. Gurlain says. “The issue, quite frankly, is the patient’s reputation.”

I shift in my seat. “Who’s the patient?”

“Lenora Hope.”

I haven’t heard that name in years. At least a decade. Maybe two. Hearing it now makes me look up from my lap, surprised. More than surprised, actually. I’m flabbergasted. An emotion I’m not certain I’ve experienced before. Yet there it is, a sort of anxious shock fluttering behind my ribs like a bird trapped in a cage.

“The Lenora Hope?”

“Yes,” Mr. Gurlain says with a sniff, as if offended to be even slightly misunderstood.

“I had no idea she was still alive.”

When I was younger, I hadn’t even understood that Lenora Hope was real. I had assumed she was a myth created by kids to scare each other. The schoolyard rhyme, forgotten since childhood, worms its way back into my memory.

At seventeen, Lenora Hope

Hung her sister with a rope

Some of the older girls swore that if you turned out all the lights, stood in front of a mirror, and recited it, Lenora herself might appear in the glass. And if that happened, look out, because it meant your family was going to die next. I never believed it. I knew it was just a variation on Bloody Mary, which was completely made up, which meant Lenora Hope wasn’t real, either.

It wasn’t until I was in my teens that I learned the truth. Not only was Lenora Hope real, but she was local, living a privileged life in a mansion several miles outside of town.

Until one night, she snapped.

Stabbed her father with a knife

Took her mother’s happy life

“She is very much alive,” Mr. Gurlain says.

“God, she must be ancient.”

“She’s seventy-one.”

That seems impossible. I’d always assumed the murders occurred in a different century. An era of hoop skirts, gas lamps, horse-drawn carriages. But if Mr. Gurlain is correct, that means the Hope family massacre took place not too long ago, all things considered.

I do the math in my head, concluding that the killings were in 1929. Only fifty-four years ago. As the date clicks into place, so do the final lines of the rhyme.

“It wasn’t me,” Lenora said

But she’s the only one not dead

Which is apparently still the case. The infamous Lenora Hope is alive, not so well, and in need of care. My care, if I want the assignment. Which I don’t.

“There’s nothing else available? No other new patients?”

“I’m afraid not,” Mr. Gurlain says.

“And none of the other caregivers are available?”

“They’re all booked.” Mr. Gurlain steeples his fingers. “Do you have a problem with the assignment?”

Yes, I have a problem. Several of them, starting with the fact that Mr. Gurlain obviously still thinks I’m guilty but, without further evidence, has no legal grounds to fire me. Since the suspension didn’t drive me away, he’s trying to do it by assigning me to care for the town’s very own Lizzie Borden.

“It’s just, I’m not—” I fumble for the right words. “Considering what she’s done, I don’t think I’d feel comfortable taking care of someone like Lenora Hope.”

“She was never convicted of any crime,” Mr. Gurlain says. “Since she was never proven guilty, then we have no choice but to believe she’s innocent. I thought you of all people would appreciate that.”

Music starts up in the aerobics studio next door, muffled behind the shared wall. “Physical” by Olivia Newton-John. Not about aerobics, although I bet those housewives working out in ripped sweatshirts and leg warmers don’t care. They’re simply content to be wasting money fighting off middle-age pudge. A luxury I can’t afford.

“You know how this works, Kit,” Mr. Gurlain says. “I make the assignments, the caregivers follow them. If you’re uncomfortable with that, then I suggest we part ways permanently.”

I would love to do just that. I also know I need a job. Any job.

I need to start building back my savings, which has dwindled to almost nothing.

Most of all, I need to get away from my father, who’s barely spoken to me in six months. I remember with a clarity so sharp it could break skin the last full sentence he directed my way. He was at the kitchen table, reading the morning paper, his breakfast untouched. He slapped the newspaper down and pointed to the headline on the front page.

A floating feeling overcame me as I stared at it. Like this was happening not to me but to someone playing me in a bad TV movie. The article included my yearbook photo. It wasn’t good, as photos go. Me trying to muster a smile in front of that blue backdrop set up in the high school gymnasium that appeared muddy and gray when rendered in dots of ink. In the picture, my feathered hair looked exactly the same as it did that morning. Numbed by shock, my first thought was that I needed to update my hairstyle.

“What they’re saying’s not true, Kit-Kat,” my father said, as if trying to make me feel better.

But his words didn’t match his devastated expression. I knew he’d said it not for my sake, but for his. He was trying to convince himself it wasn’t true.

My father threw the newspaper into the trash and left the kitchen without another word. He hasn’t said much to me since then. Now I think about that long, fraught, suffocating silence and say, “I’ll do it. I’ll take the assignment.”

I tell myself it won’t be that bad. The job is only temporary. A few months, tops. Just until I have enough money saved up to move somewhere new. Somewhere better. Somewhere far away from here.

“Wonderful,” Mr. Gurlain says without a hint of enthusiasm. “You’ll need to report for duty as soon as possible.”

I’m given directions to Lenora Hope’s house, a phone number to call if I have trouble finding it, and a nod from Mr. Gurlain, signaling the matter is settled. As I leave, I sneak a glance at the bulletin board behind his desk. Currently, three caregivers are without assignments. So there are others available. The reason Mr. Gurlain lied about that isn’t lost on me.

I’m still being punished for breaking protocol and tarnishing the agency’s sterling reputation.

But as I push out the door into the biting air of October in Maine, I think of another reason I was given this assignment. One more chilling than the weather.

Mr. Gurlain chose me because Lenora Hope is the one patient nobody—not even the police—will mind if I kill.