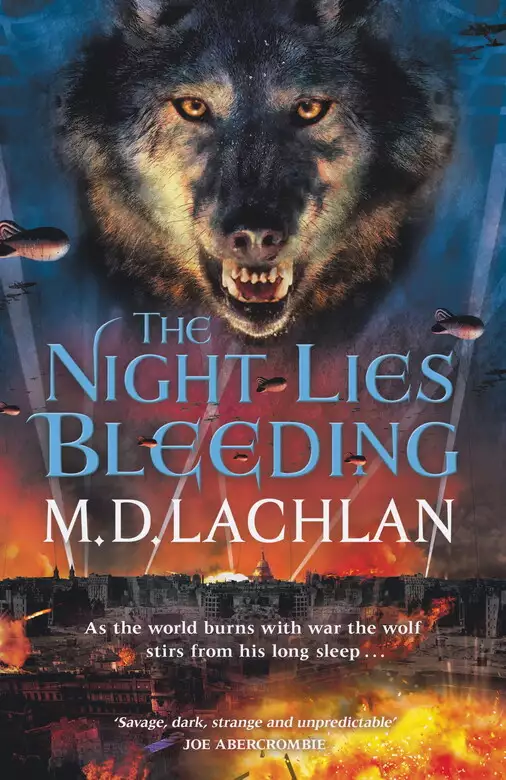

The Night Lies Bleeding

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

The world is at war again. London is suffering from the German Blitz. For one immortal werewolf, the war means little. He knows he will soon have to give up his identity once more, begin a new life. Before the wolf emerges. But a chance conversation leads him to the scene of a gruesome murder, and the realisation that another war is being fought. The runes want to be together, and the when they are the wolf's story will end. And in Germany, one weak-willed doctor finds himself caught up in the Third Reich's fascination with the occult and the Norse myths. They believe that the runes will bring them power, and wish to abuse them for their own ends. And if they succeed, Ragnarok will come.

Release date: February 22, 2018

Publisher: Gollancz

Print pages: 477

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Night Lies Bleeding

M.D. Lachlan

The full moon had always brought him peace before. But as Endamon Craw looked out from his rooftop over lightless London, he thought it more like some grisly lantern searching out the corners and nooks of the city so that Death might see clearly to take his pick.

In the distance a low voice seemed to murmur beyond the clouds, as if some mumbling giant was trying to say its names in words more familiar to Craw than the English he had been speaking for two centuries: Heinkel, Dornier, Junkers. Death was coming in on motors and wings, under the bomber’s moon.

Craw had watched London’s light change for decades, from the weak glow of the first gas lamps, to the burning incandescence of the arc light, to the softer silver that had lain over the city in the years before the war. Now the city was flat black, under an old dark, with the moon shimmering off the rooftops as if off the surface of a lake. He felt an ache in his guts. Humanity at its old game – destruction. He held up his hand.

‘Stop,’ he said. ‘Turn back. Be brave for love, not hate.’

But he was not a magician and the rumble of engines grew louder.

‘Will there be anything else, sir?’

At his shoulder was an old man in tails, holding a tray upon which was balanced a shaking bottle. Although Craw strived to keep a modern home, he still couldn’t imagine life without the help. He was still a feudalist at heart.

‘More whisky,’ he said.

The old man took Craw’s glass, placed it on the tray, and poured it out with an unsteady hand. It wasn’t age that caused him to tremble, but fear.

‘I would go to my wife, sir,’ said the man. ‘She’s in the shelter and …’

Craw started, like someone remembering that they’d left their umbrella on the train.

‘My dear Jacques, I’m so sorry,’ he said. ‘I forget … Go to her, and take the rest of the whisky. A man needs to get his courage from somewhere on a night like tonight.’

‘It’s the last of it, sir,’ said the butler.

Craw waved his hand, his familiar gesture of dismissal, and smiled.

‘We all must suffer at times like these.’

The old man withdrew and left Craw looking out down Crooms Hill towards the Thames, thinking of his own love, Adisla, so long gone. Was she being reborn tonight, on the other side of the world, or was she about to die beneath the bombs, calling for him an inch out of earshot? He remembered her, by the fjord on a hillside, the sun making a halo of her hair. And then? Just a jumble of images down the centuries, without order or sense, whose meaning flashed fleetingly in his mind before falling away to nothing. He loved her, felt that love as powerful as a tidal rip pulling him towards her down the centuries. But the meaning of that love, the detail, came to him only in fugitive glimpses.

A thousand years of transformations, of the wolf rising and falling inside him. His mind was like a sword, broken to pieces, melted down and recast. Still a sword, yes, but the same one that had been broken? He recalled a long time underground, a prison of darkness where the wolf had set him free, the reek of the prisoners, the fear of those who had tried to oppose him. Why he had been there, what he had been doing, was a mystery to him. He knew languages he had no memory of ever speaking, recalled a line of verse or conversation from five hundred years ago but could not say who had spoken it, or to whom he had been speaking. Tiny details from a millennium before came back to him – the moon through the roof of a shattered church, the turf saddle of a Viking horse. But the plot of his life was lost. Only she remained – Adisla – his need of her a lighthouse to his thoughts. If ever that went, he thought, then he would be no more than a beast – purposeless, watching the sun rise and fall, kingdoms come and go, without feeling or comprehension.

Death had followed him, he recalled that – the terrified faces, the flailing arms, the spears jabbing uselessly at him, the swords bouncing from his skin. How many had he killed looking for her? He swallowed another gulp of the whisky, taking the drinker’s gamble – heads it makes me forget, tails it makes me remember.

The sirens sang out their lament and searchlights lit the night, hunting the enemy, little moons circling their parent. In minutes came the flares. The pathfinding aircraft were on their mark. Huge burning candles dropped over London on parachutes, beautiful in their way, like angels descending, whiting out the parts of the city that the moon had missed. They turned the river into a shining avenue to guide the bombers home.

The anti-aircraft fire began, the Bofors guns’ dull hammering like an insistent visitor who wouldn’t go away, the flak bursting in the sky. Incendiaries rained down, phosphorous white blooming into lilies of flame as they settled around the river.

Then came the main body of the raid, the dark mass of bombers becoming visible in the silver light, crossing the moon as witches do in children’s tales.

The first bombs proper fell, a few cowardly crews dropping early over Shooters Hill and Thamesmead and Erith, before they hit the thickest of the ack-ack defending the docks. The distant crump, crump, crump was like a giant treading over snow, plumes of fire dogging his steps as he approached.

On the whole, though, the Germans held their nerve until they reached their target. Craw knew them for brave men, warriors from a long line of warriors. Down the centuries he had fought alongside them and fought against them. They had always impressed him.

The city under flame was a beautiful thing, greens, reds, oranges and blues blooming from the soil of the dark like a summer garden. Craw’s finger drew out a shape in the air, like the head of an arrow, an absent-minded gesture, sketching out the Kenaz rune, the Viking sign of rebirth by fire that he’d learned at the court of King Forkbeard of the Rygir, whose ward he had been over a thousand years before. He shivered. Change was on the wind.

Now the enemy was above him. He felt strange pressures in his nose and ears as the bombs pushed hot walls of air towards him and artificial vortexes rushed into the vacuums of the fires.

Craw spoke to Death.

‘Come on,’ he said, in the old language, ‘here I am. Can’t you hear me? Can’t you see me? It’s me, your servant.’

But Death didn’t want him. He wanted the Davis family sheltering under the stairs at Number 16: Dr Davis, who had just looked in to check on his family, Mrs Davis, all the children, and Pluto the dog. He wanted the newly wed Mrs Andrews at Number 4 with her funny stories and engaging smile, and he wanted old Mr Parsons at Number 23, the one who’d killed the girl and said she’d run away, the one who deserved it most, next to Endamon Craw himself.

‘Help them,’ he said, though he didn’t know who to. The old Gods of his fathers would delight to see such destruction. Christ? Surely a god of compassion could not look down on this and do nothing. Those who say the gods are creatures of love have a lot of evidence to ignore, he thought.

He watched the last drops of his whisky evaporate in the burning night and, on an impulse, dropped his glass over the edge of the roof. It caught the firelight as it fell towards the earth, a little Lucifer ejected from his heaven.

He felt giddy as he watched it fall and smash. Despite the heat of the flames he was cold; prickles ran down the back of his neck. His transformations had never been easy on him. He could recall very little of them but he remembered their beginnings at least, that restless, almost adolescent mental itch where he simply did not know what to do with himself. He didn’t want to stand up, he didn’t want to sit down; he didn’t want stay in, but he didn’t want to go out; he was hungry, but for nothing that the larder could provide.

From what he remembered of the previous times, things had begun slowly – a subtle shift in his perception, flavours and smells becoming more intense, concentration more difficult. On this occasion there had been a definite starting point.

It had been midnight and he had been in his study. The tranquil light of the Anglepoise lamp, the sparkling amber of the brandy decanter, a handmade Egyptian cigarette by Lewis of St James’s and a copy of St Thomas Aquinas’ Quaestiones disputatae de malo were his only company.

And then he had felt it – the cut. It ripped into him as if it would split him in two. It was a familiar agony, that of a sword blow. Craw had been wounded before, but always he had seen his opponent. Here, it was as if some invisible attacker had struck him as he sat in his armchair, jolting his book and his brandy to the floor, leaving him bent double and gasping for breath. The pain shot straight to the centre of his chest and he would have feared it was a heart attack, had he thought himself susceptible to such things.

Twenty minutes later, he pulled himself to his feet, all discomfort gone. He had become aware of a noise, an odd rhythmless drumming from downstairs and he had gone to investigate. A light had been left on in the scullery and a moth was beating itself against the Bakelite lampshade. Craw had sat down on a bench and pondered the implications of that. He had heard it from three floors away.

The wolf, he thought, was rising in him. It could be in a year, it could be in ten years, but it was coming, as sure as the tears of Mr Andrews as he tried to dig his wife from the wreckage of their home, as sure as Mr Andrews himself would one day die.

Craw had known the feeling many times before – the fates wanted their wolf. He looked out into the night, beyond the flames, beyond the city, into the encircling dark. Somewhere out there, he sensed, was the reason why.

2 The Gone

Daylight, and Craw sensed visitors. From Crooms Hill, London lay out before him in the sun like a continent. Even after twenty lifetimes, the sheer size of the city could still take his breath away.

Out of the window of his top floor study he could see the damage of the night before, the houses opened up into ramshackle theatre sets. Some fires were still burning, the smoke rising in the cold October air and giving the impression of something just minted, rather than destroyed.

The trams had survived the attack and were gliding through the streets like buildings on skates, as if looking for gaps to fill. There were enough of those and yet, no matter how battered and broken, life went on.

Every time you looked out after a raid it seemed things should be more destroyed than they were. But the trams moved, the shops were open. Normality was robust, it appeared, and yet you knew things were changing beyond retrieving. The grocer’s was next to the bank, which was next to a hole, which was next to the butcher’s, which was next to another hole. Each raid would leave more holes, but how many holes were needed before it would no longer be a street but just one big hole? How many bites can a moth take from a coat before it ceases to be a coat?

In a way Craw found the damage exhilarating.

The bombs imposed their own order on the city, cutting their own avenues and squares according to their type and number. A stick of incendiaries might unite Number 59 Eton Avenue with Number 68 Fellows Road, down to Number 38 Wadham Gardens and Number 3 Elsworthy Road, burning a path through the city which to Craw almost seemed polite. ‘You preferred the road running this way, but have you considered what it would look like going north?’ said the firebombs, marking the new path with the charred stumps of timbers running through the houses like a dragon’s back.

Then there were the butterfly bombs that shredded your flesh if they caught you in the open but did little damage to buildings, just breaking windows and blasting away plaster, as if the shops and houses had come down with chickenpox. The landmines were less subtle, floating down sweetly on their parachutes before tearing out a chunk of nine or ten homes and leaving a gap like a palazzo in Hell. After every raid the morning light changed as, shorn of a tower here, a gasometer there, spaces where there had been walls, the city awoke to new horizons. But the cost, the human cost. So many precious things burnt and shredded, loves, desires gone, the music of the soul stilled.

The morning confirmed his fears. The wolf was awake inside him, for certain. The world seemed brighter to the wolf, its colours more intense like in a film. Not exactly Technicolor, more like the first Kinemacolor films he’d seen, when the reds and greens had danced around their subjects in peculiar auras, as if God was a child who had selected the brightest colours but not quite got the hang of keeping them inside the borders of the shapes they were meant to fill.

Then there were the smells: aromas, scents, stinks and fumes rising up from the streets in a palette of odours both grisly and enticing. The wider sensations of his wolf mind swept over him like the feeling of relief like when you suddenly remember that name that was on the tip of your tongue. It was as if a piece of lost knowledge had returned to him, and as if he was more fundamentally himself than he had been without it. There was rain coming from the west, from beyond the blue sky. Then there was cordite, the mould of building dust, a hundred shades of burning, from curtains, to skin and hair, to the morning toast of the still-surviving houses. There was a burst sewer that any human would have found repulsive, but which the werewolf found pungent and intriguing. He was coming alive to a city of smears and secretions: his own sweat on the glass top of his desk; the sour mothballs and cheap tobacco that trailed after his butler; the pigeon droppings on the balcony; vinegar on the window panes; mould in the wood of the windows; road grime and dust. The world seemed gloriously stained.

He could not allow himself to enjoy the sensations too much and he lit a cigarette, banishing the overwhelming biology of the streets from his nostrils.

Smell is the sense that is most linked to memory. Even the dull nostrils of humans are gateways to the past, to kisses we had forgotten, angers we had thought quenched. Wet newspaper can recall the delivery job held as a child, a bonbon can put us outside a shop, reaching up to our mother.

Under the city’s odorous assault the werewolf’s memories seemed to engulf him in a way he found frustrating and disturbing. Yes, the cordite recalled the Great War, yes, the building dust took him back to Constantinople’s walls as they crumbled under the cannons, but there were other connections that were more troubling. Why did that smell of burning recall his childhood, a blonde girl on a hillside? Why did it make him think of her, and of love?

It is not just the physical creature that is torn and rearranged when a werewolf changes. The mind warps too, like a piece of metal bent in the hand that you can never quite put straight again. The smells were roads that led to the past but, for Endamon Craw, some were impassable, overgrown, ruptured and cratered. He could look down them but could not see them to their ends. Parts of himself, he knew, had been torn away by what lived inside him. At this distance of years, did he remember? Or did he remember what he had remembered, that memory itself a memory of a memory of a memory of a memory – his past coming down to him in a series of Chinese whispers whose final message might or might not reflect the original one spoken.

A wolf smells nothing as keenly as fear. London seemed to hang in an acid fog of terror left over from the night before. The sweat lying on corpses, the spilled guts, the vomit and the piss were not blown away by the relief of morning. The cortisol and adrenaline hormones that had pumped from the glands of the population under the bombs smelled sweet and appetising. He drew the sharp smoke of his cigarette onto the back of his throat. Cigarette smoke, Craw thought, was unique in the world of smells, in that it sent the mind to the future – the next cigarette – rather than into the past, that garden of snares.

The bell rang downstairs. A Detective Constable Briggs and a Detective Inspector Balby were coming to see him on urgent and confidential business. He’d received their telegram the day before. Telegram was the only way to communicate with Craw. He had put a telephone into his home just as soon as they were available. It had, however, represented the most enormous threat to his repose, ringing at all sorts of unexpected moments. The final straw had been when it had gone off during dinner. His commitment to the modern age was insistent, but there were limits as to what a gentleman could bear. He had sent it back before it could cause any more chaos.

Two men were led in, one small and powerfully built, around fifty, with a thick neck and shaved head. He had the demeanour of a man who could be smacked over the head with a spade without it disturbing his breakfast. This was Inspector Balby. The other was tall and slim, with a look to him more like an academic than a policeman. This was Constable Briggs, thirty-five years old – the thug. On him, Craw could smell blood.

The butler made the introductions and the men shook hands. Craw could never quite overcome his distaste for this – the encroaching meritocracy, greeting these men as equals. In a sane world they would bow, not touch him. One of the appeals of the house on Crooms Hill was that its Victorian plumbing provided different water mains for the servants and the masters. To him, drinking water from the same source as the help was the thin end of the wedge. Still, he knew that his distaste would pass as all his opinions passed or, rather, came in and out like the tide. He willed himself to like the informality and forget who he had been. Welcoming the future – delighting in it, even – was a condition of his sanity. Everyone, he reminded himself, is constructed. It’s up to you if you have a hand in the building.

‘You look well, sir,’ said Briggs. It was not a compliment. Any man of Craw’s age should have been sporting the swollen face of a firefighter after the previous night.

Craw smiled. ‘Thank you, Constable.’

Even if Craw had wanted to fight the fires, he was forbidden to. His job, which he had not wanted but had been given, was as master curator for the London museums and antiquities. He was chosen not for his knowledge of the past but for his eye to the future. He decided what could be moved to safety – where it was moved to and how it was stored – and what would have to wait a while under the bombs. His was the task of deciding what was history and what was ashes. The government deemed him too important to lose, and so he was mandated to spend his evenings in a Whitehall shelter, something he contrived to avoid.

He wouldn’t have gone on fire-watch even if he’d been free to do so. It would have been as demeaning to him to man a hose as to cower in a hole. Craw did not like war but, when he did participate, he preferred to do so directly. His family motto, given to him by King Charles I of Sicily in 1274, expressed it neatly: Iugulum – The Throat. It had inspired Craw’s modern name.

Craw’s study would have led a casual observer to deduce that the room belonged to some interior designer or avant-garde artist. Balby, however, was perhaps the least casual observer Craw had encountered in five centuries. Watchful by inclination, the inspector had trained any remaining sniff of lackadaisical attention from himself in thirty years of diligent police work. His title was Inspector, but it could have also described his personality.

He had been in many rooms in the course of his career, but he had never been in one like this. It was very large for a living space, and had clearly had several walls removed to make it that way. There was so little in it, too. Balby had expected strange native heads, weapons, photographs of expeditions, and all manner of native tat from an anthropologist. This place was virtually bare and everything that was in it was as new as in a showroom.

Balby had never seen such a room of chrome and leather. There was a desk with a glass top which struck him as dangerous, a cube of an armchair that looked very uncomfortable, and bookcases that seemed very ill-designed for holding books. They were no more than strips of pale wood. There were no curves or comforts, or even carpet on the polished wooden floor, just a plain-as-porridge rug.

He thought of his own wife, Lily, who had been taken in the 1919 influenza. ‘Frill it up, Jack!’ she would have said. And he would have done, because he liked to please her.

He also noted, because not much missed him, that there was only one representation of a living human being in the room – a stark black and white photograph of Craw himself looking out from a sleek silver frame on top of the desk. Beyond that there was not so much as a snap of a wife, a lover, a favourite nephew or a pet.

Besides what Balby considered the hugely egocentric photograph, the room’s only other adornments were three large pictures. The one above the brushed steel fireplace was no more than a collection of smudges and lines that he thought a child could have done. The other was a large reproduced advertisement, of all things, for the record-breaking Coronation Scot steam train which ran between London and Glasgow. Why anyone would want an advert on their wall was beyond Balby; there were enough of them outside, weren’t there?

Only one painting struck a jarring note. It was on the wall with the tall window in it. It was an old thing for such a modern room, a collection of three boards with a background of Byzantine gold. The painting itself was done in some sort of powdery oils. Balby knew nothing about art, but he looked on the strange, flattened but not flat, faces, the ornate halos, the rich golds and reds, and he had a feeling that the painting must be both very old and also foreign. On the centre board a young woman with blonde plaits sat holding a child at a strange angle, a small figure of a man at each shoulder. Two boards served as wings, each with two larger figures of men. The woman’s face, he thought, was extraordinary – evaluating, cold almost, but expressing a yearning and a restlessness that made you think that any second she might get up and run away.

‘Taddeo Gaddi, Madonna and Child Enthroned with Angels and Saints,’ said Craw.

There she was – Adisla, looking down at him from the wall. He’d found her through the visions of an Arab hermit in the Rub al Khali desert, the Empty Quarter. The man was a descendant, it was said, of the mystical tribe of Ad, hated by God, they of the lost city of Iram of the Pillars. Forty years of meditation in the sands, under the heat of the sun and the cold of the stars, living off scorpions, rats and the bitter desert flowers, sucking the water from the rocks of fugitive springs, had retuned the hermit’s mind to the frequency his ancestors had known. He recognised Craw for what he was – one of the cursed. That meant he could connect with him. The man had touched him and said ‘sleep’. Craw had awoken in the morning knowing exactly where he had to go to find his love.

He’d raced from the towering sands, down the camel trail that the frankincense merchants had abandoned a thousand years before when the dunes had turned from hills into mountains, through Persia and Turkey where, at Antalya, he had taken a Venetian glass galley to Italy, buying his place with a seat at the oars, then on over the Apennines, running with the wolf packs through the forests, and down into Florence itself, to the church of Santo Stefano that he had seen in the visions the hermit had lent him. And there she was, staring out at him from the altarpiece, a hundred and fifty years dead. He had taken it with him, encountering some difficulty with the priests. There had been blood.

‘The lady is extraordinary, don’t you think?’ said Craw.

He remembered so little of her; only snatches of conversations – those, and the dull ache of his bond of love. How many times had she been reborn? How many times had he failed to find her over how many human lives?

Balby snorted. To a man of his persuasion, saints and Madonnas were idols, plain and simple.

The painting aside, the spare and tidy space of Craw’s rooms appeared to the policeman like something from a silly story in the newspaper – life as it will be lived in the year 2000 – and it all looked as if it had been put up ten minutes before they walked in.

It would normally have made Balby suspect Craw of being a poseur or a dandy, or even a homosexual. Craw, however, looked like a serious man. He was on the short side of average, dark and pale and sharply suited, more like an architect than an academic. Balby had noted the signet ring when they shook hands. He found its wolf’s head motif a little, well, suspicious.

‘A very interesting room, sir,’ said Briggs, as if ‘interesting’ was a quality of dubious legality.

The policeman perched himself uncertainly on the sofa. It seemed too deep for him to sit on it properly.

‘Yes, officer,’ said Craw, ‘it’s the Bauhaus style – do you know it?’

‘Sounds German to me,’ said Briggs.

‘How insightful of you, it is German. From the design school at Dessau.’ The policemen exchanged a look. ‘If you’re interested I could put you in contact with a dealer.’

‘I shan’t be wanting any Nazi furniture, sir,’ said Briggs. He too had seen the ring.

‘Well then, this would be ideal for you. The Nazis shut the school down. Degenerate art, you see.’

‘I thought you said it was German,’ said Briggs.

‘Not all Germans are Nazis,’ said Craw.

‘And not all Englishmen aren’t,’ said Briggs, who tended to view conversations as a sort of toned-down fight.

Craw smiled. ‘Shall we get to business, gentlemen? Please, Inspector Balby, sit down. This is 1940 and manners are no longer the thing.’ His eyes flicked towards the seated Briggs.

Craw was mildly annoyed at the implication he was a Nazi. Nothing so low born, he. The upstart Hitler had been a corporal, a dirty, sweating, toiling corporal. How could the proud princes of the Rhine, who traced their right back beyond Charlemagne, allow themselves to be ruled by such a creature? At least Britain was led by a man of the blood.

‘Professor Craw,’ began Balby, ‘we have reason to believe …’

(My God, Craw thought, they really say ‘we have reason to believe’.)

‘… you may be able to help us. You are an anfro— An anthara—’

Balby was an intelligent man but not a learned one. His brain ran to practical pursuits. He left the long words to the coroners and the judges. Craw did not try to help him with the word.

‘Antharapologist,’ he finished.

Craw lowered his eyelids in assent.

‘Specialising in …’ Balby paused over the next words too, not because they were unfamiliar, but because he disapproved of the ideas that they raised.

‘Systems of belief,’ said Craw. ‘When I’m allowed the time to get on with my proper work.’

‘Heathen systems of belief,’ said Balby.

‘All systems.’

‘I hope not Christianity, sir.’ There was one subject capable of cracking Balby’s professional demeanour – that of the living Christ.

‘That too,’ said Craw.

Balby rocked his shaved head from side to side, like the boxer he had once been loosening up for a bout.

‘Christianity is not a system of belief, sir, it is the word of God.’

Craw had no wish to enter a debate with a believer because, as he had found down the centuries, you cannot debate with a believer. Believers believe, they don’t question. If you want a debate you had to pick a debater, people of very different mindsets. A change of subject might be appropriate, he thought.

‘Perhaps, Inspector, you and the constable would like a drink after your long journey. Shall I ring for my man? I’m afraid all we have is advocaat. The last of the whisky went last night, and it may be a day or two before we can get any more.’

‘My church doesn’t allow alcohol, sir,’ said Balby.

‘I find nothing against it in the Bible,’ said Craw.

‘I don’t know which Bible you’re reading,’ said Briggs, with a short laugh. He had never read it himself, though he tried – unsuccessfully – to kid his boss that he had.

‘Well, I prefer it in the French, the vulgate. The language sings, don’t you find? So much more so than the vetus Latina.’

He instantly regretted his flippancy. When you’ve lived so long you learn many different ways of being. You can try them on like clothes and discard them like last season’s fashion. This is not to fight boredom, it is to remain sane. If you simply are what you are then you get left behind, become a relic.

The aloofness of the English upper classes of the 1920s and 1930s, their refusal to treat anything seriously, the lightness of the jeunesse dorée, had appealed to Craw, but sometimes he became carried away. He didn’t want to belittle people; to him they were already little. Mortals exuded a strange sort of sadness, even in the fullness of their youth. Like cut flowers, he thought, they were beautiful and must die. He had no wish to add to their woes in the brief moment of their lives.

‘Alcohol is the drink of the devil, sir,’ said Balby.

Craw smiled. ‘In the case of advocaat we are in agreement, Inspector. It’s not a drink, it’s an assault on a perfectly good brandy. You should prosecute.’

‘I don’t prosecute, sir,

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...