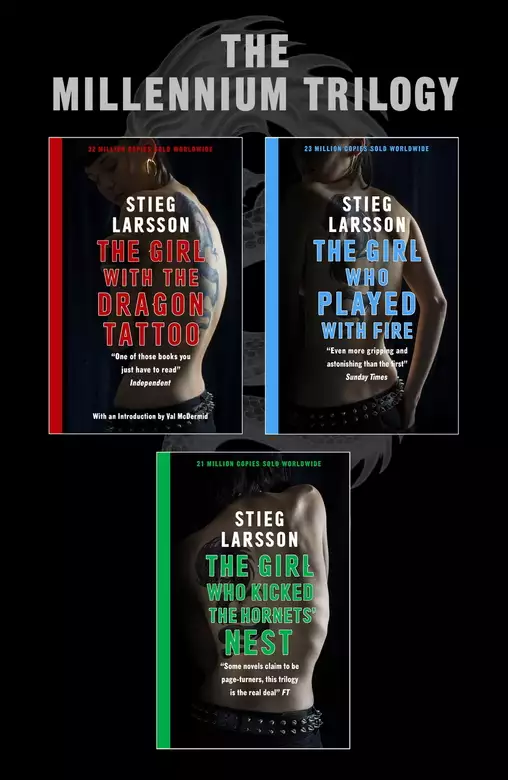

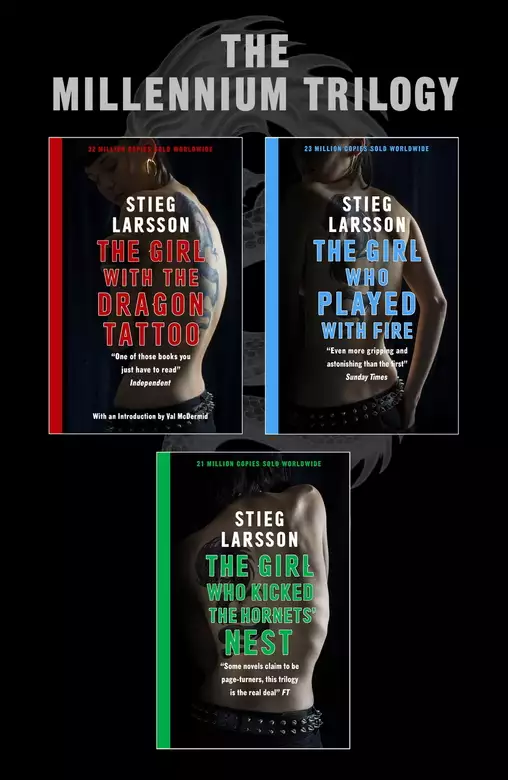

The Millennium Trilogy

- eBook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Discover the books that changed the way the world reads crime - Stieg Larsson's phenomenal global blockbuster, the Millennium Trilogy

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo: Forty years ago, Harriet Vanger disappeared from a family gathering on the island owned by the powerful Vanger clan. Her uncle employs disgraced journalist Mikael Blomkvist and tattooed hacker Lisbeth Salander to investigate. When the pair link Harriet's disappearance to a number of grotesque murders, they begin to unravel a dark family history...

The Girl Who Played With Fire: Lisbeth Salander is now a wanted woman, on the run from the police. Mikael Blomkvist, editor-in-chief of Millennium magazine, is trying to prove her innocence. Yet Salander is more avenging angel than helpless victim. She may be an expert at staying out of sight - but she has ways of tracking down her most elusive enemies.

The Girl Who Kicked the Hornets' Nest: Salander is plotting her final revenge - against the man who tried to kill her, and against the government institutions that very nearly destroyed her life. With the help of journalist Mikael Blomkvist and his researchers at Millennium magazine, Salander is ready to fight to the end.

Stieg Larsson's phenomenal trilogy is continued in The Girl in the Spider's Web and The Girl Who Takes an Eye for an Eye by David Lagercrantz.

Release date: March 23, 2016

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 1888

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Millennium Trilogy

Stieg Larsson

A Friday in

November

It happened every year, was almost a

ritual. And this was his eighty-second birthday. When, as usual, the flower was

delivered, he took off the wrapping paper and then picked up the telephone to call

Detective Superintendent Morell who, when he retired, had moved to Lake Siljan in

Dalarna. They were not only the same age, they had been born on the same day – which

was something of an irony under the circumstances. The old policeman was sitting

with his coffee, waiting, expecting the call.

“It arrived.”

“What is it this year?”

“I don’t know what kind it is. I’ll have to get someone

to tell me what it is. It’s white.”

“No letter, I suppose.”

“Just the flower. The frame is the same kind as last

year. One of those do-it-yourself ones.”

“Postmark?”

“Stockholm.”

“Handwriting?”

“Same as always, all in capitals. Upright, neat

lettering.”

With that, the subject was exhausted, and not another

word was exchanged for almost a minute. The retired policeman leaned back in his

kitchen chair and drew on his pipe. He knew he was no longer expected to come up

with a pithy comment or any sharp question which would shed a new light on the case.

Those days had long since passed, and the exchange between the two men seemed like a

ritual attaching to a mystery which no-one else in the whole world had the least

interest in unravelling.

The Latin name was Leptospermum (Myrtaceae) rubinette. It was a plant

about ten centimetres high with small, heather-like foliage and a white flower with

five petals about two centimetres across.

The plant was native to the Australian bush and uplands,

where it was to be found among tussocks of grass. There it was called Desert Snow.

Someone at the botanical gardens in Uppsala would later confirm that it was a plant

seldom cultivated in Sweden. The botanist wrote in her report that it was related to

the tea tree and that it was sometimes

confused with its more common cousin Leptospermum

scoparium, which grew in abundance in New Zealand. What distinguished

them, she pointed out, was that rubinette

had a small number of microscopic pink dots at the tips of the petals, giving the

flower a faint pinkish tinge.

Rubinette was altogether an

unpretentious flower. It had no known medicinal properties, and it could not induce

hallucinatory experiences. It was neither edible, nor had a use in the manufacture

of plant dyes. On the other hand, the aboriginal people of Australia regarded as

sacred the region and the flora around Ayers Rock.

The botanist said that she had never herself seen one

before, but after consulting her colleagues she was to report that attempts had been

made to introduce the plant at a nursery in Göteborg, and that it might, of course,

be cultivated by amateur botanists. It was difficult to grow in Sweden because it

thrived in a dry climate and had to remain indoors half of the year. It would not

thrive in calcareous soil and it had to be watered from below. It needed

pampering.

The fact of its being so rare a flower

ought to have made it easier to trace the source of this particular specimen, but in

practice it was an impossible task. There was no registry to look it up in, no

licences to explore. Anywhere from a handful to a few hundred enthusiasts could have

had access to seeds or plants. And those could have changed hands between friends or

been bought by mail order from anywhere in Europe, anywhere in the Antipodes.

But it was only one in the series of mystifying flowers

that each year arrived by post on the first day of November. They were always

beautiful and for the most part rare flowers, always pressed, mounted on watercolour

paper in a simple frame measuring fifteen by twenty-eight centimetres.

The strange story of the flowers had never

been reported in the press; only a very few people knew of it. Thirty years ago the

regular arrival of the flower was the object of much scrutiny – at the National

Forensic Laboratory, among fingerprint experts, graphologists, criminal

investigators, and one or two relatives and friends of the recipient. Now the actors

in the drama were but three: the elderly birthday boy, the retired police detective,

and the person who had posted the flower. The first two at least had reached such an

age that the group of interested parties would soon be further

diminished.

The policeman was a hardened veteran. He would never

forget his first case, in which he had had to take into custody a violent and

appallingly drunk worker at an electrical sub-station before he caused others harm.

During his career he had brought in poachers, wife beaters, con men, car thieves,

and drunk drivers. He had dealt with burglars, drug dealers, rapists, and one

deranged bomber. He had been involved in nine murder or manslaughter cases. In five

of these the murderer had called the police himself and, full of remorse, confessed

to having killed his wife or brother or some other relative. Two others were solved

within a few days. Another required the assistance of the National Criminal Police

and took two years.

The ninth case was solved to the police’s satisfaction:

which is to say that they knew who the murderer was, but because the evidence was so

insubstantial the public prosecutor decided not to proceed with the case. To the

detective superintendent’s dismay, the statute of limitations eventually put an end

to the matter. But all in all he could look back on an impressive career.

He was anything but pleased.

For the detective, the “Case of the Pressed Flowers” had

been nagging at him for years – his last, unsolved and frustrating case. The

situation was doubly absurd because after spending literally thousands of hours

brooding, on duty and off, he could not say beyond doubt that a crime had indeed

been committed.

The two men knew that whoever had mounted the flowers

would have worn gloves, that there would be no fingerprints on the frame or the

glass. The frame could have been bought in camera shops or stationery stores the

world over. There was, quite simply, no lead to follow. Most often the parcel was

posted in Stockholm, but three times from London, twice from Paris, twice from

Copenhagen, once from Madrid, once from Bonn, and once from Pensacola, Florida. The

detective superintendent had had to look it up in an atlas.

After putting down the telephone the

eighty-two-year-old birthday boy sat for a long time looking at the pretty but

meaningless flower whose name he did not yet know. Then he looked up to the wall

above his desk. There hung forty-three pressed flowers in their frames. Four rows of

ten, and one at the bottom with four. In the top row one was missing from the ninth

slot. Desert Snow would be number forty-four.

Without warning he began to weep. He surprised himself

with this sudden burst of emotion after almost forty years.

CHAPTER 1

Friday, 20.xii

The trial was irretrievably over; everything that could be said had been said,

but he had never doubted that he would lose. The written verdict was handed

down at 10.00 on Friday morning, and all that remained was a summing-up from

the reporters waiting in the corridor outside the district court.

Carl Mikael Blomkvist saw them through the doorway and slowed his step. He had no

wish to discuss the verdict, but questions were unavoidable, and he – of all

people – knew that they had to be asked and answered. This is how it is

to be a criminal, he thought. On the other side of the

microphone. He straightened up and tried to smile. The

reporters gave him friendly, almost embarrassed greetings.

“Let’s see… Aftonbladet, Expressen, T.T. wire service,

T.V.4, and… where are you from?… ah yes, Dagens Nyheter.

I must be a celebrity,” Blomkvist said.

“Give us a sound bite, Kalle Blomkvist.” It was a reporter from one of

the evening papers.

Blomkvist, hearing the nickname, forced himself as always not to roll his eyes.

Once, when he was twenty-three and had just started his first summer job as

a journalist, Blomkvist had chanced upon a gang which had pulled off five

bank robberies over the past two years. There was no doubt that it was the

same gang in every instance. Their trademark was to hold up two banks at a

time with military precision. They wore masks from Disney World, so

inevitably police logic dubbed them the Donald Duck Gang. The newspapers

renamed them the Bear Gang, which sounded more sinister, more appropriate to

the fact that on two occasions they had recklessly fired warning shots and

threatened curious passers-by.

Their sixth outing was at one bank in Östergötland at the height of the holiday

season. A reporter from the local radio station happened to be in the bank

at the time. As soon as the robbers were gone he went to a public telephone

and dictated his story for live broadcast.

Blomkvist was spending several days with a girlfriend at her parents’ summer

cabin near Katrineholm. Exactly why he made the connection he could not

explain, even to the police, but as he was listening to the news report he

remembered a group of four men in a summer cabin a few hundred metres down

the road. He had seen them playing badminton out in the yard: four blond,

athletic types in shorts with their shirts off. They were obviously

bodybuilders, and there had been something about them that had made him look

twice – maybe it was because the game was being played in blazing sunshine

with what he recognised as intensely focused energy.

There had been no good reason to suspect them of being the bank robbers, but

nevertheless he had gone to a hill overlooking their cabin. It seemed empty.

It was about forty minutes before a Volvo drove up and parked in the yard.

The young men got out, in a hurry, and were each carrying a sports bag, so

they might have been doing nothing more than coming back from a swim. But

one of them returned to the car and took out from the boot something which

he hurriedly covered with his jacket. Even from Blomkvist’s relatively

distant observation post he could tell that it was a good old AK4, the rifle

that had been his constant companion for the year of his military service.

He called the police and that was the start of a three-day siege of the cabin,

blanket coverage by the media, with Blomkvist in a front-row seat and

collecting a gratifyingly large fee from an evening paper. The police set up

their headquarters in a caravan in the garden of the cabin where Blomkvist

was staying.

The fall of the Bear Gang gave him the star billing that launched him as a young

journalist. The down side of his celebrity was that the other evening

newspaper could not resist using the headline “Kalle Blomkvist solves

the case”. The tongue-in-cheek story was written by an older

female columnist and contained references to the young detective in Astrid

Lindgren’s books for children. To make matters worse, the paper had run the

story with a grainy photograph of Blomkvist with his mouth half open even as

he raised an index finger to point.

It made no difference that Blomkvist had never in his life used the name Carl.

From that moment on, to his dismay, he was nicknamed Kalle Blomkvist by his

peers – an epithet employed with taunting provocation, not unfriendly but

not really friendly either. In spite of his respect for Astrid Lindgren –

whose books he loved – he detested the nickname. It took him several years

and far weightier journalistic successes before the nickname began to fade,

but he still cringed if ever the name was used in his hearing.

Right now he achieved a placid smile and said to the reporter from the evening

paper:

“Oh come on, think of something yourself. You usually do.”

His tone was not unpleasant. They all knew each other, more or less, and

Blomkvist’s most vicious critics had not come that morning. One of the

journalists there had at one time worked with him. And at a party some years

ago he had nearly succeeded in picking up one of the reporters – the woman

from She on T.V.4.

“You took a real hit in there today,” said the one from Dagens Nyheter,

clearly a young part-timer. “How does it feel?”

Despite the seriousness of the situation, neither Blomkvist nor the older

journalists could help smiling. He exchanged glances with T.V.4. How

does it feel? The half-witted sports reporter shoves his

microphone in the face of the Breathless Athlete on the finishing line.

“I can only regret that the court did not come to a different conclusion,” he

said a bit stuffily.

“Three months in gaol and 150,000 kronor damages. That’s pretty severe,” said

She from T.V.4.

“I’ll survive.”

“Are you going to apologise to Wennerström? Shake his hand?”

“I think not.”

“So you still would say that he’s a crook?” Dagens Nyheter.

The court had just ruled that Blomkvist had libelled and defamed the financier

Hans-Erik Wennerström. The trial was over and he had no plans to appeal. So

what would happen if he repeated his claim on the courthouse steps?

Blomkvist decided that he did not want to find out.

“I thought I had good reason to publish the information that was in my

possession. The court has ruled otherwise, and I must accept that the

judicial process has taken its course. Those of us on the editorial staff

will have to discuss the judgment before we decide what we’re going to do. I

have no more to add.”

“But how did you come to forget that journalists actually have to back up their

assertions?” She from T.V.4. Her expression was neutral, but

Blomkvist thought he saw a hint of disappointed repudiation in her eyes.

The reporters on site, apart from the boy from Dagens Nyheter, were all

veterans in the business. For them the answer to that question was beyond

the conceivable. “I have nothing to add,” he repeated, but when the others

had accepted this T.V.4 stood him against the doors to the courthouse and

asked her questions in front of the camera. She was kinder than he deserved,

and there were enough clear answers to satisfy all the reporters still

standing behind her. The story would be in the headlines but he reminded

himself that they were not dealing with the media event of the year here.

The reporters had what they needed and headed back to their respective

newsrooms.

He considered walking, but it was a blustery December day and he was already cold

after the interview. As he walked down the courtroom steps, he saw William

Borg getting out of his car. He must have been sitting there during the

interview. Their eyes met, and then Borg smiled.

“It was worth coming down here just to see you with that paper in your hand.”

Blomkvist said nothing. Borg and Blomkvist had known each other for fifteen

years. They had worked together as cub reporters for the financial section

of a morning paper. Maybe it was a question of chemistry, but the foundation

had been laid there for a lifelong enmity. In Blomkvist’s eyes, Borg had

been a third-rate reporter and a troublesome person who annoyed everyone

around him with crass jokes and made disparaging remarks about the more

experienced, older reporters. He seemed to dislike the older female

reporters in particular. They had their first quarrel, then others, and anon

the antagonism turned personal.

Over the years, they had run into each other regularly, but it was not until the

late ’90s that they became serious enemies. Blomkvist had published a book

about financial journalism and quoted extensively a number of idiotic

articles written by Borg. Borg came across as a pompous ass who got many of

his facts upside down and wrote homages to dot-com companies that were on

the brink of going under. When thereafter they met by chance in a bar in

Söder they had all but come to blows. Borg left journalism, and now he

worked in P.R. – for a considerably higher salary – at a firm that, to make

things worse, was part of industrialist Hans-Erik Wennerström’s sphere of

influence.

They looked at each other for a long moment before Blomkvist turned on his heel

and walked away. It was typical of Borg to drive to the courthouse simply to

sit there and laugh at him.

The number 40 bus braked to a stop in front of Borg’s car and Blomkvist hopped on

to make his escape. He got off at Fridhemsplan, undecided what to do. He was

still holding the judgment document in his hand. Finally he walked over to

Kafé Anna, next to the garage entrance leading underneath the police

station.

Half a minute after he had ordered a caffè latte and a sandwich, the lunchtime

news came on the radio. The story followed that of a suicide bombing in

Jerusalem and the news that the government had appointed a commission to

investigate the alleged formation of a new cartel within the construction

industry.

Journalist Mikael Blomkvist of the magazine Millennium was sentenced

this morning to ninety days in gaol for aggravated libel of industrialist

Hans-Erik Wennerström. In an article earlier this year that drew attention

to the so-called Minos affair, Blomkvist claimed that Wennerström had used

state funds intended for industrial investment in Poland for arms deals.

Blomkvist was also sentenced to pay 150,000 kronor in damages. In a

statement, Wennerström’s lawyer Bertil Camnermarker said that his client was

satisfied with the judgment. It was an exceptionally outrageous case of

libel, he said.

The judgment was twenty-six pages long. It set out the reasons for finding

Blomkvist guilty on fifteen counts of aggravated libel of the businessman

Hans-Erik Wennerström. So each count cost him 10,000 kronor and six days in

gaol. And then there were the court costs and his own lawyer’s fee. He could

not bring himself to think about all the expenses, but he calculated too

that it might have been worse; the court had acquitted him on seven other

counts.

As he read the judgment, he felt a growing heaviness and discomfort in his

stomach. This surprised him. As the trial began he knew that it would take a

miracle for him to escape conviction, and he had become reconciled to the

outcome. He sat through the two days of the trial surprisingly calm, and for

eleven more days he waited, without feeling anything in particular, for the

court to finish deliberating and to come up with the document he now held in

his hand. It was only now that a physical unease washed over him.

When he took a bite of his sandwich, the bread seemed to swell up in his mouth.

He could hardly swallow it and pushed his plate aside.

This was the first time that Blomkvist had faced any charge. The judgment was a

trifle, relatively speaking. A lightweight crime. Not armed robbery, murder

or rape after all. From a financial point of view, however, it was serious –

Millennium was not a flagship of the media world with

unlimited resources, the magazine barely broke even – but the judgment did

not spell catastrophe. The problem was that Blomkvist was one of

Millennium’s part-owners, and at the same time, idiotically

enough, he was both a writer and the magazine’s publisher. The damages of

150,000 kronor he would pay himself, although that would just about wipe out

his savings. The magazine would take care of the court costs. With prudent

budgeting it would work out.

He pondered the wisdom of selling his apartment, though it would break his heart.

At the end of the go-go ’80s, during a period when he had a steady job and a

pretty good salary, he had looked around for a permanent place to live. He

ran from one apartment showing to another before he stumbled on an attic

flat of seventy square metres right at the end of Bellmansgatan. The

previous owner was in the middle of making it liveable but suddenly got a

job at a dot-com company abroad, and Blomkvist was able to buy it

inexpensively.

He rejected the original interior designer’s sketches and finished the work

himself. He put money into fixing up the bathroom and the kitchen area, but

instead of putting in a parquet floor and interior walls to make it into the

planned two-room apartment, he sanded the floorboards, whitewashed the rough

walls and hid the worst patches behind two watercolours by Emanuel

Bernstone. The result was an open living space, with the bedroom area behind

a bookshelf, and the dining area and the living room next to the small

kitchen behind a counter. The apartment had two dormer windows and a gable

window with a view of the rooftops towards Gamla Stan, Stockholm’s oldest

section, and the water of Riddarfjärden. He had a glimpse of water by the

Slussen locks and a view of City Hall. Today he would never be able to

afford such an apartment, and he badly wanted to hold on to it.

But that he might lose the apartment was nothing beside the fact that

professionally he had received a real smack in the nose. It would take a

long time to repair the damage – if indeed it could ever be repaired.

It was a matter of trust. For the foreseeable future, editors would hesitate to

publish a story under his byline. He still had plenty of friends in the

business who would accept that he had fallen victim to bad luck and unusual

circumstances, but he was never again going to be able to make the slightest

mistake.

What hurt most was the humiliation. He had held all the trumps and yet he had

lost to a semi-gangster in an Armani suit. A despicable stock-market

speculator. A yuppie with a celebrity lawyer who sneered his way through the

whole trial.

How in God’s name had things gone so wrong?

The Wennerström affair had started out with such promise in the cockpit of an

eleven-metre Mälar-30 on Midsummer Eve a year and a half earlier. It began

by chance, all because a former journalist colleague, now a P.R. flunky at

the county council, wanted to impress his new girlfriend. He had rashly

hired a Scampi for a few days of romantic sailing in the Stockholm

archipelago. The girlfriend, just arrived from Hallstahammar to study in

Stockholm, had agreed to the outing after putting up token resistance, but

only if her sister and her sister’s boyfriend could come too. None of the

trio from Hallstahammar had any sailing experience, and unfortunately

Blomkvist’s old colleague had more enthusiasm than experience. Three days

before they set off he had called in desperation and persuaded him to come

as a fifth crew member, one who knew how to navigate.

Blomkvist had not thought much of the proposal, but he came round when promised a

few days of relaxation in the archipelago with good food and pleasant

company. These promises came to naught, and the expedition turned into more

of a disaster than he could have imagined. They had sailed the beautiful but

not very dramatic route from Bullandö up through Furusund Strait at barely

nine knots, but the new girlfriend was instantly seasick. Her sister started

arguing with her boyfriend, and none of them showed the slightest interest

in learning the least little thing about sailing. It quickly became clear

that Blomkvist was expected to take charge of the boat while the others gave

him well-intentioned but basically meaningless advice. After the first night

in a bay on Ängsö he was ready to dock the boat at Furusund and take the bus

home. Only their desperate appeals persuaded him to stay.

At noon the next day, early enough that there were still a few spaces available,

they tied up at the visitors’ wharf on the picturesque island of Arholma.

They had thrown some lunch together and had just finished when Blomkvist

noticed a yellow fibreglass M-30 gliding into the bay using only its

mainsail. The boat made a graceful tack while the helmsman looked for a spot

at the wharf. Blomkvist too

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...