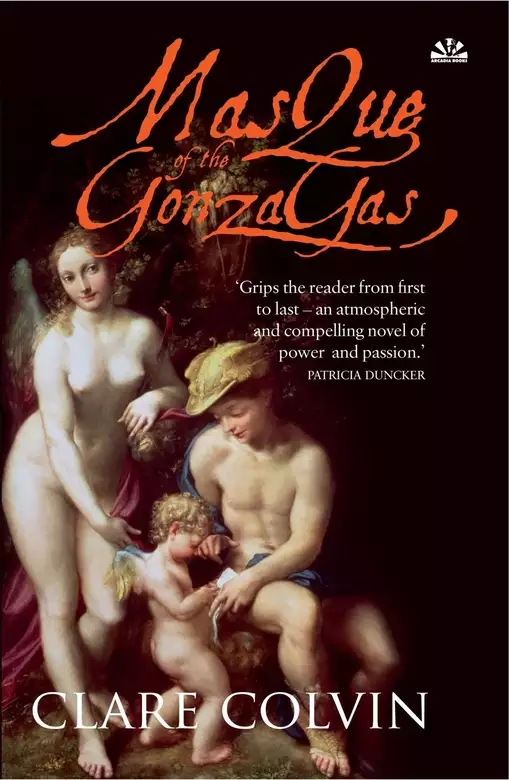

The Masque of Gonzagas

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

The baroque era at the beginning of the 17th century: change and upheaval are undermining the certainties of the Renaissance. In northern Italy, amid political and religious dissent, Vincenzo Gonzaga, 4th Duke of Mantua, devotes himself to the pursuit of excellence and pleasure. He gathers to his court the finest painters and musicians. His composer, Claudio Monteverdi, creates his first opera, La Favola d'Orfeo. Clare Colvin's novel follows the Renaissance dream of Arcadia to its horrific destruction, drawing on letters and documents of the time to resolve one of history's most fascinating riddles. What was the reason for the ambivalent relationship between the Duke and his court composer? Why did the Gonzagas destroy themselves, bringing chaos to Italy? And what role did the seductive Isabella of Novellara play in their downfall?

Release date: January 2, 2007

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Masque of Gonzagas

Clare Colvin

How could we live without mirrors? They are the windows through which we see ourselves. Look at you now, glancing into them as you pass by. And there is another to look at, and another. This is the Hall of Mirrors, reflecting your two images, how you are, how you would like to be. Glance at the mirror knowingly, and you see how you would like to be. Catch yourself unwittingly and there’s a stranger.

Do you like our Hall of Mirrors? You’re looking up at the ceiling, at the four horses and the charioteer. I watch you cross over to the other side of the room, and you see the horses galloping in the opposite direction. An optical illusion, like so many of our frescoes. We play with dimensions.

All you can see in the room is emptiness and yourself reflected in the mirrors. Can you not hear, if only faintly, music through the shroud of time? Can you not hear the people? Do you not feel the attention, the hush in the air? They are no longer glancing at the mirrors and at each other, but intent on the musicians and on the thin figure in black who directs. I have seen his back curved over his viol many times, I am more interested in watching the faces of those who watch him, so I stand at the side, my eyes on the mirror reflecting the audience.

I am watching the Duke. Have you noticed his eyes, how pale and visionary they are in the portraits? That is how they look now, absorbed in the music of our magician. I have seen his different expressions over the years, the wild humour, the speaking fire as he looks at a woman, the canny glint as he juggles one debt against another, the icy hardness of a murderer. A many-faceted man, our Duke Vincenzo: mean and generous, profligate and careful, kind and cruel. And vain, gloriously vain, but why not? If you were born to that splendour, wouldn’t you be?

Look at the Duchess Eleonora beside him. The serenity of her face, tempered by twenty-seven years married to the greatest libertine of our day. Not a cold man, you understand, but one so overwhelmed by the bounty of love inside him that he cannot help but bestow it on others. She is pale from a grippe. It is January in this year of 1611 and the winds blow over the Mantuan marshes even to the cloistered corners of the palace. She is in her middle years, there have been five children, and she has had year after year of this harsh climate, the burning summers, the iron winters, the marsh fevers that come with the rain. We are close to the earth here. Despite our gilding, our trompe l’œil and our mirrors, we are ruled by the seasons.

Eleonora is unwell. Isabella is in black. She buried Don Ferrante four years ago, but black suits her. I see her glance at the Duke, and their eyes meet for a moment, then she looks at the mirror and catches my eye, as I knew she would. There is no one as guileless and knowing as our Isabella. She wept inconsolably when Ferrante died and then was happier than she had been for years: who can blame her? Out of her isolation and back at court.

Tonight Vincenzo has only eyes and ears for the music, and for his new singer, the incomparable Adriana. She is considered the greatest, the most dramatic, the most beautiful of our day. As soon as Vincenzo heard of her, he wanted her. It was a matter of principle. Mantua must have the best art, the best music. We will show the Medici, we will show the Emperor himself. Our walls where they are not mirrored, glow with the works of Titian and Rubens. Our Director of Music is the best in Italy, the divine Claudio. Duke Vincenzo knew as soon as he saw him over twenty years ago in Cremona, a young violist, and then again at Florence. No one can resist the Duke when he claims possession, not even Adriana, despite her protestations of honour. Have you seen her villa? Have you seen her carriages, her jewels? Are you aware of how much the court treasurer is paying her? Twenty times the salary of our Director of Music. No wonder Monteverdi looks pained. When he is not at his music, the only thought that runs through his mind is how are we going to live? He is thin because he is driven, and because there is hardly enough to eat in his house. His poor children.

But listen to Adriana, how her voice soars and laments, and we weep with her. The wonder of so much emotion engendered – the two of them, the melancholy, driven man, and the woman who lives for gifts, Adriana Cupidity Basile, look at the effect they have had on the audience, with his music and her voice. The Duke has tears in his eyes, they have become blue lakes, overbrimming onto his reddened cheeks. He has a lot to weep about, of course, and at times like this he is free to do so. At other times he keeps the demons at bay with his perpetual motion, his frantic travelling, his insatiable buying of treasures and of people. When will he ever find peace? That must be what Eleonora asks herself, though by now she doesn’t expect an answer.

I know as much about the Duke as anyone. I stay in the shadows now, but he is aware of me. He may have forgotten the time, years long ago, when we talked until dawn. The philosophy of Plato, the writing of Ficino, Mirandola, Giordano Bruno, the cabbala, the alchemy of elements and much else. Keeping the spirit of enquiry alive in a world that was becoming enclosed by dogma. The Inquisitor finally arrived at Mantua – the slanderer, we called him. The books at the palace that he would have burned had he access to them.

I remember Vincenzo reading to me from Bruno: ‘Unless you make yourself equal to God, you cannot understand God, for the like is not intelligible save to the like. Believe that nothing is impossible for you, think yourself immortal and capable of understanding all arts, all sciences, the nature of every living being. Mount higher than the highest height, descend lower than the lowest depth. Draw into yourself all sensations of everything created, on earth, in the sea, in the sky, in the womb, beyond death. If you embrace in your thought all things at once, times, places, substances, then you may understand God.’

Vincenzo has lived this philosophy. He has risen higher, descended lower than any of us. Yet he still does not understand God, for he has not found peace. And he is jealous of Monteverdi, he can hear through his music that Claudio is in communication with God, with the gods. As I am jealous of Vincenzo, not as he is now but as he was then: a young god of love, handsome, tall, his fair hair, as always, unruly, his eyes alight with life, a healthy mountain complexion from his Austrian mother. And I, like his father, stunted by the marshes, twisted by the wind, a thorn tree next to the ash. Everyone knows I am jealous, it is part of my nature, but no one knows Vincenzo’s envy of the divine gift. Does he himself know? Look at the labyrinth ceiling for his answer, the words that are carved, twisting and turning through the maze. Forse che si, forse che no. Maybe yes, maybe no. What kind of a man chooses such a motto?

Step through the mirror and I will show you the pictures.

Here is a loggia overlooking a lake, a young man sitting on the parapet, one foot resting on it, displaying what he knows is a fine calf in repose. His shirt is open at the neck, his jerkin loosely fastened. He is dressed for a morning’s hunting, but he had risen late and there had been one delay after another. Secretaries flapping documents at him, messages from the Treasury. And so on, etcetera, und so weiter.

It is a soft spring morning, and Vincenzo is restless. There are too many people at his heels and ever more demands on his time. It is calming to look out over the waters of the lakes surrounding Mantua, their far shores fringed by willows that ripple from green to silver in the breeze. His hair is similarly ruffled by the wind, fair and resilient to the comb.

‘Look at the old grandfathers along the bank, they’re out in force today,’ he says. ‘Pike tonight for everyone.’

There, leaning against the next arch of the loggia, I can see the young man who was myself, Ottavio. He is wearing a grey cloak carefully draped at the back, obscuring his body. He is around twenty years old, his hair dark, his eyes with a darting sideways glance, as if trying to catch what is happening out of his sight. He is holding a letter in his outstretched hand, which the Duke ignores. Eventually he flicks it to attract his attention.

‘She wants all her letters returned. Every one of them. She has listed the dates.’

Vincenzo sighs. ‘That it comes to this. All that passion spent and now we have to make an inventory of her love letters. Why did she write so many? I don’t know where they are. In this drawer or that. The hound Magnus ate one of them, I remember. I gave it to him to sniff the perfume, and he dripped saliva all over it, so I let him keep it.’

‘She is very insistent, and more than a little anxious.’

Vincenzo’s voice had risen a note, as it did when he felt put upon. ‘What does she think I am going to do with her damned letters? Send them to her husband? Hand them out in the piazza? I’ve a mind to, the lack of trust she shows in me, Ottavio. No one could have been more careful with her secrets than I.’

Ottavio smiles, remembering the passages the Duke had read aloud. He says, ‘Nevertheless, she is insistent. We will have to return those we can find.’

‘Ottavio, will you do that for me? I can’t bear the thought of looking through the letters, of people asking me what I am searching for. Do it in the afternoon when no one is in the office. You know where the keys are.’

‘Tidying up after His Highness.’

‘And you do it so well.’ Vincenzo directs his warmest smile, his eyes shining with the love of humanity. No man or woman could resist the charm. Ottavio folds the letter and slides it into his sleeve.

Vincenzo leans over the parapet to watch the fishermen. One of them has waded into the lake and is waiting to grasp at a gliding shape. He picks up a pebble from under the lemon tree and spins it so that it lands near the man with a splash like a rising trout. The fisherman lunges at the ripples; his dog, which had seen the missile, leaps into the lake barking. The man curses the dog. The other fishermen shout at him. Vincenzo laughs.

‘Such a small thing, and look at the trouble it causes.’

He glances at the entrance to the loggia, and the warmth fades from his face. A girl is standing on the topmost step, her hair loose on her shoulders, the stiff bodice of her dress giving her the appearance of a marionette; her age, around fourteen years. She is poised as though for flight, but at the same time riveted with curiosity. She stares at the Duke as if at a magnificent, mythological beast.

‘Who is that?’ Vincenzo’s face, unusually for him, betrays anxiety.

‘She is from Novellara. A second cousin, related on my mother’s side. You met her mother, Donna Vittoria, yesterday. They are guests of the Duchess.’

‘For a moment…’ says Vincenzo, and paused. His unspoken thought is clear to Ottavio. For a moment he had remembered Margherita Farnese, his first wife, callously chosen in a game of politics by Vincenzo’s father when she was too young, no more than a child; too frightened of love, and now condemned to a convent, the loss of her future the subject of rancour between the houses of Mantua and Parma.

The girl is looking at Vincenzo with open curiosity. He holds out a welcoming arm. ‘La bella ragazza. Che bella! Have you come to look at me, or at the view?’

Giggling bursts out from her two friends on the steps behind her. She raises a hand to her mouth, her eyes looking with adult awareness at the man before her. As he stands up, she retreats and all three girls run down the stairs in a flurry of skirts and giggles.

‘Already an eye for men,’ says Vincenzo. ‘What is her name?’

‘Isabella. From Novellara.’

‘One fine day…’ as he looks out over the water, and then, ‘Now Ottavio, what are you going to do for me?’

‘I am going to find all of the Signora’s letters, apart from those the dog has eaten, and return them to her.’

‘Tie them with a golden ribbon and pearls, so it seems we are returning something precious, rather than being thankfully rid of them.’

So that is our Duke for you, Vincenzo Gonzaga, young and careless, in both senses of the word. An extraordinary vitality runs in his veins. That, more than his fine figure, more than his considerable wealth, is what attracts all to him. He seems alight with life, and those around him feel more alive. And the almost innocent joy he gets from the riches his father left him is quite touching. I can see his face now as he emerged from his first visit to the strong-rooms, and described the millions of gold scudi, the jewels, the title deeds, the files of credit notes, carefully hoarded by the miserly Duke Guglielmo. Who was no longer there to place a restraining hand on his son. Our Duke pounced on the gold like a hound among truffles.

There is, though, a sort of divine discontent in the way he uses his wealth. It is not enough to spend, he needs to create with it as well: to create beautiful things, awe-inspiring events, to create wonder. He was an adolescent when he first visited the d’Este court at Ferrara and heard the concerte delle donne. He breathed in the beauty of their voices and the music, and as soon as he was Duke, with access to the treasury, he set about acquiring musicians and singers from Ferrara, from Venice and from Florence, in competition with his wife’s uncle, the Grand Duke Ferdinando.

Eleonora de’ Medici is no fool, she knows that it is not just for art he has brought to Mantua the finest singers, and a permanent company of actors. People laugh about the Duke’s musical harem, and once in a while a girl with a fine voice returns home and is never heard of again. It gives us something to gossip about.

Do you detect a note of jealousy? I have a tainted vein of the blood that runs through the family’s branches, emerging now and then in twisted bodies, stunted limbs. You can hardly see, I drape my cloak so expertly it looks little more than a stoop. Unlike Vincenzo’s father, who was a veritable hunchback. Duke Guglielmo il Gobbo. We are men of the marshland; our strength is in our survival, you should not expect beauty as well.

Let us move to the next picture, from the profane to the sacred. You are in a cathedral, see the soaring columns, like avenues of stone trees, their branches ending in a filigree supporting the painted roof. Hear the purity of the voices praising Our Lady of the Heavens. Do you see the young man there on the left, in his musician’s black robes, his face intent on the music, enraptured yet aware as he sings? Afterwards he will point out to his fellows in the choir where it was half a note too long. Not the best way to make himself loved, but even then he would sacrifice everything to the perfection of his music. Thin, with large dark eyes, a high forehead, a sensitive mouth. Claudio, son of the doctor Baldassare Monteverdi in Cremona, one book of madrigals already published in Venice, another about to come out in Milan. Just twenty-two and on a voyage of discovery. There are two qualities he has in common with the Duke: a consuming love of music and the same divine discontent. It is not enough for him to create music, he wants to claim the soul with it, his own, his listeners’. It is only a matter of time before the two will meet. The year is 1589. Grand Duke Ferdinando of Tuscany has cast off his Cardinal’s robes, taken his late brother’s title, and allied himself with France in his marriage to Christine of Lorraine. Neither the Habsburg Emperor nor His Most Catholic Majesty of Spain are happy to see French influence in Italy, but the Grand Duke is an astute and determined man. Claudio is aware of the politics but his interest in the wedding is to do with the musical intermedii for the comedy, La Pellegrina. From Cremona, he travels south with his fellow musicians to Florence. From Mantua Duke Vincenzo’s 600-strong retinue sets forth for the same destination.

Weddings were good for business and no city was ever more eager for business than Florence. They accepted the overcrowding, the difficulty of getting food, all supplies having been requisitioned by the Grand Duke, because in the end they would be the richer for it. No one richer than the Grand Duke whose lavish celebrations would be compensated for by the dowry of his bride. The Florentines could even tolerate the overwhelming number of Mantuans on the loose, talking in their loud, harsh dialect, walking four abreast in the street, jostling each other and anyone in their way, not out of ill will but simply because they are used to the wide open spaces around their own city and feel enclosed by hills.

The Mantuan retinue numbered 200 men at arms as well as the entire court and its attached entertainers, including a coachload of dwarfs who were getting under everyone’s feet. The splendour of their trappings and costumes were a statement of vanity, designed to impress the French and the Florentines. Grand Duke Ferdinando trusted that the scale of his entertainments would redress the balance. He had borrowed Duke Vincenzo’s favourite singers, the Pellizari sisters, but the composers and writers were Florentine, and the designer the great Buontalenti, the Medici architect.

Circling each other, separated by rank and society, the Duke and the musician from Cremona saw the same event from their different perspectives. Claudio, in quick glances, took in the audience of nobility, their embroidered silks, stiff ruffs and swathes of pearls. On stage, the feathered headdresses, jewels and silks of the gods and muses, and the scenery, painted with as much care as if it would be there forever. Peri, the composer, costumed as Arion the poet with papier mâché harp, sang his own composition, then escaped from forty men dressed as sailors by flinging himself into the waving ribbons of the sea, causing mirth in the orchestra at the idea of ‘Lo Zazzerino’ with forty sailors after him. He should be so fortunate, muttered the musicians. And so it went on, the posing on stage, the preening in the audience, over the course of seven hours.

No one had finer feathers than the Duke of Mantua, but the showiness disguised a well-informed mind. He had noticed in all the extravaganza the young Monteverdi, he had taken soundings, he had already seen the first book of madrigals. He had an eye for promise of every sort, and knew better than to wait until it is sought-after and therefore more expensive. A week later a letter bearing the Gonzaga crest arrived at Dr Baldassare’s house in Cremona.

The new musician follows the others through a confusion of corridors, up the stone staircase, through the Room of the Zodiac, through the Room of the Falcons and the Room of the Satyrs to the Hall of the Rivers. On its walls are painted the six rivers that run through the Mantuan land, on the ceiling flights of birds, at one end a stone grotto and above it the four black spreadeagles and cross of the Gonzaga coat of arms. The musicians arrange their stands and instruments before the rows of chairs and wait for their audience. Friday night is concert night at the palace of Mantua. Every week there are new compositions as a diversion for the Duke.

You can trace the most influential in the court through looking at the first two rows. Among them is always to be found Giaches de Wert, the old Director of Music, whose shared past with the Duke during their time in Ferrara gives him a power beyond his position. He will talk to the Duke during performances, pointing out particular qualities in the music. He watches the new violist, for he already knows his compositions. He notes that the man from Cremona is used to freer air than that of Mantua’s court. As the audience applaud at the end, the Duke, his face shining above his starched ruff with enthusiasm and the heat of the evening, turns to de Wert.

‘Mantua will be the centre of the new music. We are leading the way, ahead of Florence. Why do you not play nowadays, Ottavio?’ the question being addressed to the young courtier next to de Wert, Ottavio; always in the right place.

‘Because, as Your Highness has brought in so many excellent musicians from Venice, Florence, and Ferrara, there is hardly space for a poor amateur.’

You have to use courtier’s language like that when there are others present.

‘What a load of balls you talk, Ottavio,’ says Vincenzo. ‘You play as well as anyone here,’ and then to de Wert, ‘Tell the new musician to compose a piece for Don Ottavio. I should like to see him play it next week.’

Monteverdi bows to the request, though his air is less of being honoured by a commission than of being doubtful about the musician. Anyone else would have accepted with a show of gratitude, and then cobbled together offcuts of other compositions to satisfy what had been a passing whim. Not Signor Claudio. He arrives at rehearsals pale from having worked through the night. We rehearse the new work for viols. And Monteverdi talks the special language of musicians when words give way to the sounds and the beat. ‘Now at that point it should be ta-ta te tah, semi-quaver, allegro.’ No wonder musicians stay together. No one else can understand a word that they say. Isabella arrives with her mother to watch the rehearsals for amusement, and with a little envy.

‘I could sing for the Duke,’ she says. ‘I have a good voice. You have heard it, Ottavio.’

As I had, the summer before at Novellara. In the garden of their villa, the fields around shimmering in the golden evening light, playing the lute while Isabella sang in a high, pure voice. Like an angel, her mother had said.

Her mother says now, ‘You will certainly not sing for the Duke. He might mistake you for one of the harem.’

Lucia Pellizari looks angrily at her and snaps, ‘Quiet during the rehearsals.’

Isabella smiles. She is interested in everything, even a display of temper. It is a hot day. The musicians have their collars unlaced. Lucia Pellizari fans herself with a painted fan shaped like a viol. She takes the pearls from her neck and places them on the clavichord’s lid. They are a present from the Duke. Sweat is trickling down Monteverdi’s face as he marks time from his place at the viols. It is a sign of the marsh fever.

‘From that phrase again,’ he says. ‘From the ta-ta te tah, and…’

We begin again and the music takes shape. It speaks to the heart in a way I had not heard before, like wings of angels in my chest, beating against the rib cage. I see Monteverdi’s eyes watching me as an instrument of his music, and we seem to be linked as one, myself as his viol. As the movement draws to a close, I look at our audience and see Isabella, her eyes intent on me. And I realize that something still lives under the heart of ice I had assumed with my shape. ‘You’re like the salamander,’ Vincenzo once said, ‘you lack the warmth that I have.’ But the music told me that somewhere within was the gift we are born with. ‘Why, Ottavio,’ says Isabella afterwards, touching my sleeve, ‘you looked quite beautiful when you played.’

And so it was the music that first made it seem that all things were possible. That the ugly should be beautiful, the unloved should be loved. Music, the builder of ho. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...