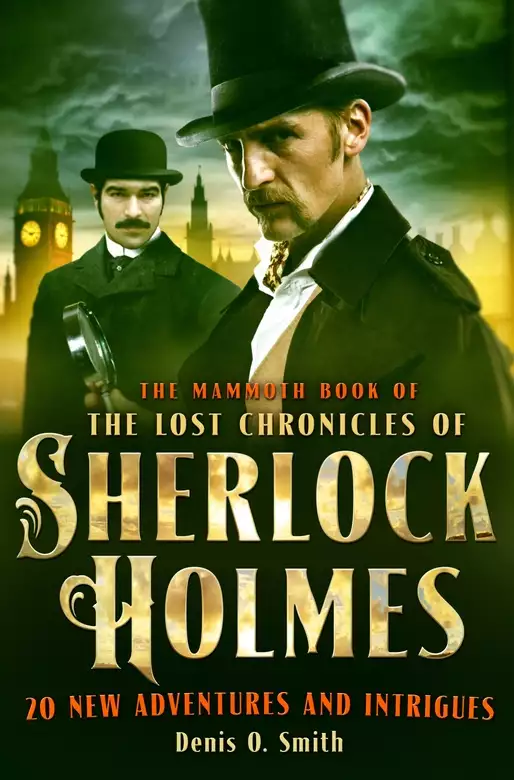

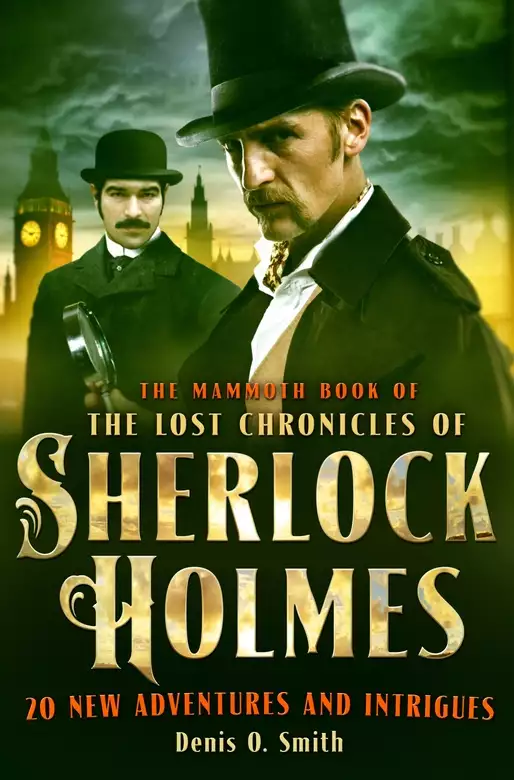

The Mammoth Book of The Lost Chronicles of Sherlock Holmes

- eBook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

These are stories of the sort loved by true fans of the greatest of all detectives, in which a client tells Holmes a strange tale, drawing him into a baffling mystery. Whether in fogbound London or deep in the English countryside, these action-packed stories, set during the 1880s and early 1890s, before Holmes’s disappearance at the Reichenbach Falls, faithfully recreate the atmosphere of Conan Doyle’s early Holmes stories.

This wonderful anthology brings together the best work of Denis O. Smith, much admired for his new Sherlock Holmes stories, including ‘A Hair’s Breadth’, ‘The Adventure of the Smiling Face’ and ‘An Incident in Society’. Ten of these stories have never previously been published in book form.

Release date: May 17, 2012

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 512

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mammoth Book of The Lost Chronicles of Sherlock Holmes

Denis O. Smith

Readers will no doubt recall that Buckler’s Fold in Hampshire was the country estate of Sir George Kirkman, a man who had amassed great wealth from his interests in metalworking, mining and railway engineering. Beginning in a modest way, as the owner of a small chain-link forge in Birmingham, he had risen rapidly, both in wealth and eminence, until a fair slice of British industry lay under his command and he had received a knighthood for his achievements.

At the time of the tragedy that was to bring the name of Buckler’s Fold to national prominence, Sir George had held the estate for some eight years. It was his custom, during the summer months of the year, to invite notable people of the day to spend the weekend there. It was said that he prided himself upon the happy blend of the celebrated who gathered at his dinner table upon these occasions, and it was certainly true that many of those renowned at the time in the worlds of arts, letters and public life had made at least one visit to Buckler’s Fold. Indeed, it was said in some circles that one could not truly be said to be established in one’s chosen field until one had received an invitation to one of Sir George Kirkman’s weekend parties.

One unusual feature of such gatherings was an archery contest for the gentlemen, which, by custom, took place on Sunday, upon the lower lawn behind the house. Sir George had in recent years developed an interest in the sport, at which he had achieved a certain proficiency, and was keen to introduce others to what he termed “the world of toxophily”.

In the early part of May, 1884, the renowned African explorer, E. Woodforde Soames, had returned to England and become at once the most sought-after guest in London. He and his companion in adventure, Captain James Blake, had spent the previous six months exploring the upper reaches of the Zambezi River, and had several times come within an inch of their lives. Many stories of their adventures circulated at the time: of how their boat had sunk beneath them in a crocodile-infested river, of how a month’s provisions had been washed away in a matter of minutes, and of how Captain Blake had saved Woodforde Soames from a giant python at Zumbo. News of the hair-raising entertainment provided by these stories soon reached the ear of Sir George Kirkman, and as he himself had played a part in organizing the finance for their expedition and, it was said, looked for some return for the time and effort he had invested, an invitation to the two men to spend the weekend at Buckler’s Fold was duly dispatched. Among the other guests that weekend, as I learned from Friday’s Morning Post, was the rising young artist Mr Neville Whiting, whose engagement to the daughter of the Commander of the Solent Squadron had recently been announced. At the time I read it, his name meant nothing to me, and I could not have imagined then how soon the name would be upon everyone’s lips, nor what a significant part in his destiny would be played by my friend Sherlock Holmes.

The newspapers of Monday morning occasionally included a brief mention of the weekend’s events at Buckler’s Fold, and when the name caught my eye on that particular morning, I glanced idly at the accompanying report. In a moment, however, I had cried out in surprise.

Holmes turned from the window, where he was smoking his after-breakfast pipe and staring moodily into the sunny street below, and raised his eyebrow questioningly.

“‘A tragic accident has occurred’,” I read aloud, “‘at Buckler’s Fold, country home of Sir George Kirkman, in which one of his guests has been struck by an arrow and killed. An archery competition is a regular feature of parties at Buckler’s Fold, and it is thought that the victim was struck by a stray shaft from this event while walking nearby. No further information is available at present.’”

“The longbow is a dangerous toy,” remarked my companion. “Hazlitt declares in one of his essays that the bow has now ceased for ever to be a weapon of offence; but if so, it is a singular thing how frequently people still manage to inflict injury and death upon one another with it.” With a shake of the head, he returned to his contemplation of the street below.

Holmes had been professionally engaged almost continuously throughout the preceding weeks, but upon that particular morning was free from any immediate calls upon his time. It was a pleasant spring day, and after some effort I managed to prevail upon him to take a stroll with me in the fresh air. Up to St John’s Wood Church we walked, and across the northern part of Regent’s Park to the zoo. It was a cheery sight, after the long cold months of the early spring, to see the blossom upon the trees and the spring flowers tossing their heads in such gay profusion in the park. As ever on such occasions, my friend’s keen powers of observation ensured that even the tiniest detail of our surroundings seemed possessed of interest.

We were walking slowly home through the sunshine, our conversation as meandering as our stroll, when we passed a newspaper stand near Baker Street station. The early editions of the evening papers were on sale and, with great surprise, I read the following in large letters upon a placard: “Arrow Murder – Latest”.

“Murder?” I cried.

“It can only refer to the death at Buckler’s Fold,” remarked Holmes, a note of heightened interest in his voice. Quickly he took up a copy of every paper available. “Listen to this, Watson,” said he, reading from the first of his bundle as we walked along. “‘The death of E. Woodforde Soames, shot in the back with an arrow at Buckler’s Fold in Hampshire yesterday, and at first reported to be an accident, is now considered to be murder. The Hampshire Constabulary were notified soon after the death was discovered. Considering the circumstances to be of a suspicious nature, they at once requested a senior detective inspector from Scotland Yard. Arriving at Buckler’s Fold at six o’clock, he had completed his preliminary investigation by seven, and proceeded to arrest one of the guests, Mr Neville Whiting, who was heard to protest his innocence in the strongest terms.’ They must have considered it a very straightforward matter, if they were able to make an arrest so quickly,” Holmes remarked as we walked down Baker Street, “although why anyone should wish to murder Woodforde Soames, probably the most popular man in England at the moment, must be regarded as something of a puzzle!”

When we reached the house, we were informed that a young lady, a Miss Audrey Greville, had called for Sherlock Holmes, and was awaiting his return. As we entered our little sitting room, a pretty, dark-haired young woman of about two-and-twenty stood up from the chair by the hearth, an expression of great agitation upon her pale features.

“Mr Holmes?” said she, looking from one to the other of us.

“Miss Greville,” returned my friend, bowing. “Pray be seated. You are, I take it, the fiancée of Mr Neville Whiting, and have come here directly from Buckler’s Fold.”

“Yes,” said she, her eyes opening wide in surprise. “Did someone tell you I was coming?”

Holmes shook his head. “You are clearly in some distress, and on the table by your gloves I see a copy of the Pall Mall Gazette, which is open at an account of the Buckler’s Fold trage dy. Next to it is the return half of a railway ticket issued by the London and South Western, and upon your third finger is an attractive and new engagement ring. Now, what is the latest news of the matter, and how may we help you?”

“Neville – Mr Whiting – has been arrested,” said she, and bit her lip hard as she began to sob. I passed her a handkerchief and she dabbed her eyes. “Forgive me,” she continued after a moment, “but it has been such a great shock.”

“That is hardly surprising,” said Holmes in an encouraging tone. “What is the evidence against Mr Whiting?”

“We had had a quarrel, earlier in the day,” the young lady replied. “He accused me of flirting with other gentlemen.”

“With Woodforde Soames?”

“Yes.”

“And were you?”

She bit her lip again. “He seemed such a grand figure,” said she at length, “and has had such exciting adventures. Perhaps I was paying him an excessive amount of attention, but if I was, it was no more than that. Neville became so jealous and unreasonable. He said that Soames’s opinion of himself was big enough already, without my making it even bigger.”

“What happened later?”

“The archery contest took place early in the afternoon. I had persuaded Neville to take part, although he said he was not interested and had never fired a longbow in his life. It was foolish of me.”

“He was not very successful?”

“He did not hit the target once. I did not think it would concern him, considering that he had said he was not interested, but perhaps I was wrong. There were seven or eight gentlemen taking part, and although one or two of the others did scarcely any better than Neville, that appeared to afford him little consolation. I think he felt humiliated. Mr Woodforde Soames was the eventual winner and, I must admit, I found myself cheering as he shot his last arrows. I looked round for Neville then, but found that he had already left the lawn. I asked if anyone had seen him, and was informed that he had gone off into the nearby woods and taken his bow and quiver with him.”

“When did you next see him?”

“About an hour and a half later. My mother and I were taking tea on the terrace when he returned. He appeared in a better humour and apologized for his earlier temper. I asked him where he had been and he said he had taken a long walk through the orchards and the woods and loosed off a few practice arrows at the trees there.”

“Was Woodforde Soames present when Mr Whiting returned?”

Miss Greville shook her head. “No,” said she. “He had gone for a walk shortly after the archery contest ended, as had several of the others. All had returned within an hour or two, except Mr Soames. Then one of Sir George Kirkman’s servants ran onto the terrace, his face as white as a sheet, and whispered something to Sir George, who then stood up and announced that one of his gamekeepers had found Mr Woodforde Soames dead in the woods. It appeared, he said, that he had been struck by an arrow. I don’t think that anyone there could believe it. Mr Soames had had an air of indestructibility about him and had, moreover, just returned unscathed from six months in the most dangerous parts of the world. That he should shortly thereafter lose his life in a wood in Hampshire seemed simply too fantastic to be true.”

“Much of life seems too fantastic to be true,” remarked Holmes drily. “What action was taken?”

“Sir George sent one of his men to notify the local police authorities. They later sent for a detective from London, who arrived early in the evening and interviewed everyone there. In little over an hour he had arrested Neville.”

“On what grounds?”

“The quarrel we had had earlier in the day had been witnessed by several people, who had overheard Neville’s wild remarks concerning Mr Woodforde Soames.”

“That is all?” said Holmes in surprise.

The young lady shook her head but did not reply immediately. “No,” said she at length. “The arrow that killed Mr Soames was one of Neville’s.”

“How was that established?”

“The shafts of the arrows were stained in a variety of colours, and each man taking part in the archery contest was given a quiver containing a dozen arrows of the same colour. Neville’s were crimson, and it was a crimson arrow that killed Mr Woodforde Soames. But, Mr Holmes,” our visitor cried in an impassioned voice, “Neville could not have done it! It is simply inconceivable! No one who knows his gentle character could believe it for an instant!”

Holmes considered the matter for a while in silence. “What is the name of the detective inspector from London?” he asked at length.

“Mr Lestrade,” replied Miss Greville.

“Ha! So Lestrade is on the trail! Is he still at Buckler’s Fold?”

“Yes. He stayed in the area last night, and returned to the house this morning to take further statements from everyone. When it came to my turn to be interviewed, I asked him if there was any possibility that his conclusions might be mistaken. He shook his head briskly and declared that the circumstances admitted of no doubt whatever.

“But is it possible, in such a case,” I persisted, “to seek a second opinion, as in medical matters, where one’s general practitioner can call upon a consultant?”

“‘There is Mr Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street,’ said he after a moment, in a dubious tone. ‘No doubt he would provide you with a second opinion, but I very much fear that it would differ little from mine. Still, I understand your relation to the accused and appreciate that you would wish to clutch at any straw.’”

“Why, the impudent scoundrel!” cried Holmes, rising to his feet. “I certainly shall give you a second opinion, Miss Greville. Would you care to accompany us, Watson?”

“Most certainly.”

“Then get your hat, my boy! We leave for Hampshire at once!”

In thirty minutes we were in a fast train bound for the south coast, and two hours later, having changed at Basingstoke, we alighted at a small wayside halt, deep in the Hampshire countryside. I have remarked before on the singular ability of Sherlock Holmes to drive from his mind those things he did not for the moment wish to consider, and our journey that day provided a particularly striking illustration of this, for having spent the first part of the journey silently engrossed in his bundle of newspapers, he had then cast them aside, and passed the remainder of the time in cheery and incongruous conversation with Miss Greville, for all the world as if he were bound for a carefree day at the coast. As we boarded the station fly, however, and set off upon the final part of our journey, a tension returned to his sharp, hawk-like features, and there was an air of concentration in his manner, like that of a hound keen to be upon the scent.

We had wired ahead from Waterloo, and upon our arrival at the house, as Miss Greville hurried off to find her mother, we were shown into a small study, where Inspector Lestrade was sitting at a desk, writing.

“Mr Holmes!” cried the policeman, turning as we entered. “I was surprised to receive your telegram – I had not expected to see you down here so quickly!”

“I felt obliged to match the speed with which you moved to an arrest,” returned Holmes. “You are confident you have the right man?”

“There is no doubt of it.”

“Then you will not mind if we conduct our own investigation of the matter.”

“Not at all. Indeed, I will show you where the crime occurred, although, in truth, there is little enough to be seen there.”

He led us along a corridor and out at a door which gave onto a paved terrace at the rear of the house. Several people were sitting there, taking tea. A large, clean-shaven, portly man stood up from a table as we passed, the rolls of fat about his jaw and throat wobbling as he did so.

“Who are these men, Inspector?” he demanded of Lestrade.

“Mr Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson, Sir George,” the policeman replied. “Miss Greville has engaged them to look into the matter on her behalf.”

“You are wasting your time,” Sir George Kirkman remarked in a blunt tone.

“A few hours spent in the pleasant Hampshire countryside is never a waste of time,” Holmes responded placidly.

Sir George Kirkman snorted. “Still,” he continued, “if the young lady insists, there is nothing to be done about it. And I suppose you would not wish to turn down an easy fee, if times are slack.”

I saw a spark of anger spring up in Holmes’s eye. “You must speak for yourself, Sir George,” said he at length, “and I will answer for my own work. Come along, Lestrade, there are clouds in the sky, and I should not wish to be hampered by rain!”

“I’ll come with you,” said Kirkman. “It will be interesting to watch an expert at work.”

We descended a steep flight of steps from the terrace to the lawn. There, Lestrade indicated a door immediately to the side of the steps, which gave access to a storeroom built under the terrace itself.

“The archery equipment is kept in here,” said he, opening the door.

Inside, hanging up behind gardening tools and similar implements, were a dozen or more longbows and quivers.

Holmes took down one of the quivers and extracted an arrow. The shaft was stained dark green. For a moment he turned it over in his hands.

“The murder weapon was crimson, I understand,” said he at length to Lestrade.

“That’s right. From the quiver that Whiting had been using.”

“It hardly proves that Whiting fired the shot,” remarked Holmes. “Surely anyone could have used one of the crimson arrows?”

Lestrade shook his head. “Each of the quivers contains twelve arrows of a single colour, and all the quivers are different – blue, green, crimson, purple and so on. Whiting took his bow and quiver off with him into the woods – to practise, he said – and did not return until much later, so it would have been impossible for anyone else to have used his arrows.”

“I understand, however,” said Holmes, “that Whiting left early, before the competition was finished.”

“That is so,” said Lestrade, “but I cannot see that that makes any difference to the matter.”

“Only this,” said Holmes, “that if the competition was still in progress when he left, it would not have been possible for Whiting to retrieve the last arrows he shot, which I understand all missed the target, and would thus be lying on the ground. Once the contest was over, and the competitors had dispersed, anyone might have picked those arrows up from the ground and used them.”

“It sounds a bit unlikely,” said Sir George Kirkman. “Of course, I realize that in murder cases, those acting for the defence must always do their best to contrive an alternative explanation, however far-fetched, to try to cast doubt on their client’s guilt.”

“Unless it can be proved that the arrow which killed Woodforde Soames came from those still in the quiver, rather than those on the ground,” continued Holmes, ignoring the interruption, “then the colour of the arrow shaft is, it seems to me, of no significance whatever. Where did Whiting leave his bow and quiver when he returned from his walk?”

“He dropped them on the ground near the targets,” said Lestrade, “on the archery field, where all the other equipment had been left at the end of the contest.”

“Were they still there when you arrived?”

“No. All the equipment had been collected up by Sir George’s servants and put away in this storeroom. I did ask them if they had observed anything unusual about the equipment – if any of it had been left in an odd place, for instance – but they said not. Some of the arrows had been lying on the ground, they said, and some had been in the quivers, but they could not remember any details.”

“In other words,” said Holmes, “no one can say with any confidence where the fatal arrow came from, nor which bow fired it. It seems to me, then, Lestrade, that most of your case against Neville Whiting collapses. Did anyone other than Whiting leave the archery field before the end of the competition?”

Lestrade shook his head. “Everyone else stayed until the end. Sir George presented a little trophy to Woodforde Soames, who had won, and then they all drifted away, some to the house and some to take a walk over the estate.”

Holmes nodded. “Has anyone left today?”

“Two Members of Parliament were obliged to return to London this morning.”

“But everyone else who was present over the weekend is still here?”

“All except Sir George’s secretary, Hepplethwaite,” Lestrade returned. “He left yesterday afternoon to visit a sick relative.”

“Have you verified the matter?” Holmes queried.

“I did not think it necessary,” Lestrade returned in surprise.

“No? Surely it is something of an odd coincidence that this man Hepplethwaite should leave the house at the same time as Woodforde Soames is killed. I should certainly have felt obliged to satisfy myself as to the truth of the matter.”

“No doubt,” responded Lestrade in a tone of irritation, “and no doubt I would have done so, too, had there been the slightest possibility that Hepplethwaite had been involved in the crime in any way. But he left the house only a few minutes after the archery competition finished, at which time Woodforde Soames was still very much alive, for he sat over a cup of tea on the terrace for some five or ten minutes at about that time, talking to various people – including Miss Greville and her mother, as it happens – before going off for his walk. That’s right, isn’t it, Sir George?”

“Absolutely,” responded Kirkman. “I had just returned to my study, shortly after presenting the archery trophy, and Woodforde Soames and the others were taking tea, as you say, when Hepplethwaite entered with a telegram he had received. It informed him that his father was ill. He asked if he might leave at once, and I agreed to the request. As far as I am aware, he left the house a few minutes later.”

“I see,” said Holmes. “Well, well. Let us now inspect the spot where Soames met his death.”

Lestrade led us across the lawn and down another flight of stone steps to a lower lawn, surrounded on three sides by trees. Along the far side, a number of wooden chairs and benches were set out. It was evidently upon this lower lawn that the archery contest had taken place, for at the left-hand end stood two large targets. Behind them, a long canvas sheet had been hung from the trees to catch any arrows that missed the targets.

We crossed the lawn at an angle, and followed Lestrade through a gap in the trees, immediately to the right of the canvas sheeting, from where a narrow path curved away into the woods. After a short distance this path was joined by another, and we followed it to the left, crossing several other smaller paths, until we came presently to a wider, well-used path which ran at right-angles to our own. Lestrade turned right onto this path and we followed its winding course for some twenty or thirty yards. The trees in this part of the wood grew very close together, and there was an air of shaded gloom about the place. Coming at last round a sharp turn to the left, we arrived at a place where the path stretched dead straight for some twenty yards ahead of us. Lestrade stopped before a small cairn of pebbles which had been placed in the middle of the path.

“I have marked the spot,” said he. “These paths wind about so much that one could easily become confused as to where one was in the wood.”

“Very good,” said Holmes in approval. Then he squatted down upon the ground and proceeded to examine with great care every square inch of the path for fifteen feet in either direction. Presently he rose to his feet, a look of dissatisfaction upon his face.

“Found what you were looking for?” asked Kirkman in an undisguised tone of mockery.

“The ground is very hard, so it is unlikely that there would be much to be seen in any case,” replied Holmes in a placid tone, “but so many feet have passed this way in the last twenty-four hours that the little there may have been has been quite obliterated.” He looked about him, peering into the dense undergrowth on either side, then walked up and down the path several times. “Soames was found face-down, stretched lengthways on the path, I take it,” he remarked at last to Inspector Lestrade.

“That’s correct, Mr Holmes,” the policeman replied. “He had been shot in the back, as you’re no doubt aware, an inch or two left of centre. The local doctor who examined the body said that the arrow had penetrated quite deeply, and he thought that death would probably have occurred within a few seconds.”

He broke off as there came the sound of footsteps behind us. I turned as a stocky, middle-sized man appeared round the bend in the path. His sunburnt face was clean-shaven, save for a small dark moustache, and there was a military precision in his manner as he stepped forward briskly and introduced himself as Captain Blake, the former companion in adventure of Woodforde Soames. He had, he said, just heard of our arrival, and asked, as we shook hands, if he might accompany us in our investigation.

“By all means,” said Holmes. “In which direction was Soames facing when he was found?” he continued, addressing Lestrade.

“With his feet pointing back the way we have come, and his head towards the straight section of the path in front of us,” Lestrade replied. “The path we are now on begins near the kitchen gardens, by the side of the house. It is evident, therefore, that he was coming from the house, or somewhere near it, and heading deeper into the woods.”

Holmes stood a moment in silence, then he shook his head.

“I disagree,” said he at length, in a considered tone.

“Why so?” asked Lestrade in surprise.

“The disposition of the body is, in this case, of less consequence than the disposition of the path,” said Holmes.

“What on earth are you talking about?” demanded Kirkman.

“I think that when struck, Soames must have turned before he fell,” Holmes continued. “The force of the blow, just below the left shoulder blade, would probably have been sufficient by itself to spin him round. But he may also have tried to turn as he fell, to see who it was that was attacking him.”

Sir George snorted dismissively, but Lestrade considered the suggestion for a moment. “It is certainly possible,” he conceded at length. “But what makes you think so, Mr Holmes?”

“See how thickly the trees are growing just here, and how dense and tall the undergrowth is. It is scarcely conceivable that anyone could have forced a passage through that, or could have had a clear sight of Woodforde Soames if he had done so. Therefore, whoever fired the shot must have been standing upon the path at the time.”

“That seems certain,” said Captain Blake, nodding his head in agreement.

“Now, behind us, in the direction of the house,” Holmes continued, “the path is very winding, whereas ahead of us, away from the house, it is fairly straight for some considerable distance. Whoever fired the shot must have had a clear view of Woodforde Soames’s back. From the direction of the house that is impossible. Immediately before this spot there is a right-angled bend in the path, and before that there are more twists and turns. From the other direction, however, the archer would have had a clear and uninterrupted view. Therefore, Woodforde Soames was shot when returning to the house from somewhere ahead of us. Where does this path lead to?”

“I do not know,” Lestrade admitted. “I saw no reason to explore the path further, as I didn’t believe that the murdered man had been any further along it than the spot we’re now standing on.”

“Does this path go anywhere in particular, Sir George?” queried Holmes.

“Not really,” Kirkman replied. “It meanders on for a mile or so, and comes out by the water-meadows near the river.”

“I understood that this was the way to the folly,” Captain Blake interjected.

“Oh, that old thing!” said Kirkman in a dismissive tone. “It is meant to look like a Roman ruin, so they tell me, but it looks just like a pile of old bricks to me.”

“Let us follow the path a little distance, anyway,” said Holmes, “and see if we can turn up anything of interest.”

“Oh, this is a complete waste of time!” cried Kirkman in an impatient voice. “I shall leave you to it,” he continued, turning on his heel and walking rapidly back towards the house as we followed Holmes further along the path.

At the end of the long straight section, the path again turned sharply to the left, and there, just a few yards further on, on the right-hand side of the path, was the mouldering, ivy-covered ruin to which Kirkman had referred. It appeared little greater in size than a small shed, but it was so smothered in creepers and brambles that its shape was difficult to discern. It was clear, however, that there was a wide arched doorway at the front, and a dark, sepulchral chamber within.

Holmes frowned as we approached this singular structure.

“Halloa!” said he. “Someone has been in here very recently!”

“How can you tell?” asked Blake.

“The cobwebs across the doorway have been recently broken. Let us have a look inside.”

He pushed aside the trailing fronds of ivy, which hung like a curtain across the entrance, and made his way into the gloom within. Captain Blake held the ivy aside, and

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...