- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

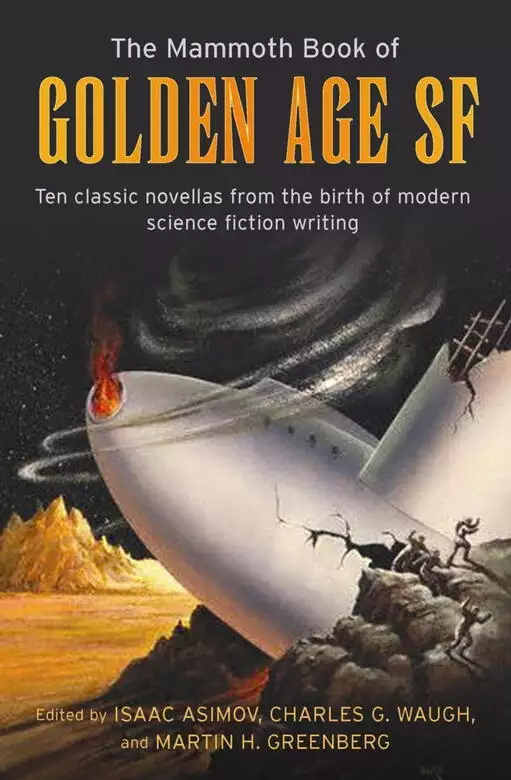

Ten classic stories from the birth of modern science fiction writing The Golden Age of Science Fiction, from the early 1940s through the 1950s, saw an explosion of talent in SF writing including authors such as Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, and Arthur C. Clarke. Their writing helped science fiction gained wide public attention, and left a lasting impression upon society. The same writers formed the mould for the next three decades of science fiction, and much of their writing remains as fresh today as it was then. Collected in one giant volume, here is the very best of the golden era. The stories include: A.E. van Vogt, 'The Weapons Shop' Isaac Asimov, 'The Big and the Little' Lester del Rey, 'Nerves' Fredric Brown, 'Daymare' Theodore Sturgeon, 'Killdozer!' C.L. Moore, 'No Woman Born' A. Bertram Chandler, 'Giant Killer'

Release date: March 1, 2012

Publisher: Robinson

Print pages: 548

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mammoth Book of Golden Age

Isaac Asimov

In the first book of the series, which dealt with classic science fiction (s.f.) novellas of the 1930s, I said that the 1930s was the decade in which science fiction found its voice. Toward the end of that decade, the voice began to resemble, more and more, that of John Wood Campbell, Jr., and in the 1940s, J.W.C. dominated the field to the point where to many he seemed all of science fiction.

It was a phenomenon that had never happened before and can never be repeated. Before the 1940s, science fiction was so small a field that, in a way, there was nothing to dominate. Hugo Gerns-back had been important in the 1920s, but he was alone. F. Orlin Tremaine had been important in the 1930s, but he did not drown out the other voices completely.

Campbell, however, towered. He had a charismatic personality that utterly dominated everyone he met. He overflowed with energy and he had his way with science fiction. He found it pulp and he turned into something that was his heart’s desire. He then made it the heart’s desire of the reader.

To put it another way, he found science fiction a side-issue written by eager fans with only the beginnings of ability, or by general pulp writers who substituted spaceships for horses, or disintegration rays for revolvers, and then wrote their usual stuff. Campbell put science fiction center stage and made it a field that could be written successfully only by science fiction writers who had learned their craft.

To put it still another way, he found science fiction a trifling thing that could only supply writers with occasional pin-money and he labored to make of it something at which science fiction writers could make a living. He could not, in the 1940s, drag the field upward to the point of making writers rich, but he laid the foundations for the coming of that time in later decades.

It is impossible for anyone ever to repeat the feat of John W. Campbell, Jr. For one thing you cannot lay the foundations for quality science fiction a second time. The foundation is there for all time and it was laid by Campbell. For another thing, the field has grown to such a pitch (thanks to Campbell) that it is too large ever to be dominated by one man. Even Campbell, larger than life though he was, if he were miraculously brought back into existence, could not dominate the field today.

So who was John Campbell? He was born in Newark, New Jersey on June 8, 1910. I have never found out much about his childhood, except that I received the impression that it was a very unhappy one. He attended M.I.T. between 1928 and 1931, but never finished his schooling there. The story I heard was that he couldn’t pass German. He transferred to Duke University.

This double experience at college was reflected in his later work. At M.I.T. he picked up his interest in science. At Duke, where R.B. Rhine was conducting his dubious experiments on extra-sensory perception, he picked up his interest in the scientific fringe. In the 1940s, science dominated Campbell’s mind, and in the 1950s the scientific fringe did. He went from M.I.T. to Duke in science fiction as well as in his college training. In this volume, however, we are concerned with his earlier phase.

He sold his first science fiction story while he was still a teenager (not unusual among the true devotees) but he was too inexperienced to keep a carbon and T. O’Conor Sloane of Amazing Stories lost the manuscript (which was unusual). It was Campbell’s second sale, then, that marked his first actual appearance. This was “When the Atoms Failed” in the January 1930, Amazing. He was still only nineteen at the time.

In those days, the greatest name among the science fiction writers was E.E. Smith, Ph.D., who had climbed to fame with his “The Skylark of Space”, a three-part serial that appeared in the August, September, and October 1928 issues of Amazing. “The Skylark of Space” featured interstellar travel and dealt with megaforces and megadistances. It was an example of what came to be called “super-science stories” and Smith made it his specialty. Naturally, others followed the trend, and Campbell did so from the start. He quickly became second only to Smith in the super-science field.

There was a difference, though Smith could not change. He remained super-science to the end. Campbell could change and did. He wanted to write science fiction less in scale and more in introspection, less with ravening forces and more with puzzling mind.

He even changed his name for the purpose, writing a series of stories as Don A. Stuart. (His first wife’s maiden name was Dona Stuart.) The first Stuart story was “Twilight” which appeared in the November 1934, Astounding Stories, a sad, haunting tale of the end of humanity. It proved an enormous hit, and instantly began the change of making science fiction smaller in scope and deeper in thought.

He wrote Stuart stories predominantly, thereafter, until he published his towering masterpiece “Who Goes There?” which appeared in the August 1938, Astounding, and which was reprinted in the first book of this series.

By October 1937, however, he had been appointed to an editorial position at Astounding and, within a few months, he was in full charge. His first significant action was to change the name of the magazine, a change which reflected his thinking. He wanted to get rid of words like “amazing”, “astounding”, and “wonder”, which stressed the shock-value and superficiality of science fiction. He wanted to call the magazine simply Science Fiction, thus merely defining its scope but allowing him to fiddle with the details at will.

Unfortunately, he was too late. Columbia Publications had already registered that name, and a magazine so-named (not at all successful) eventually appeared in the spring of 1939. Campbell was therefore forced to make only a partial change. With its March 1938 issue Astounding Stories became Astounding Science Fiction.

As editor, Campbell was a phenomenon even greater than he had been as a writer. He held open house and anyone who might conceivably help him achieve his aims was welcome. When, on June 21, 1938, a frightened eighteen-year-old, named Isaac Asimov, appeared with his first story at Street & Smith Publications, Inc. (which published Astounding), he was invited into Campbell’s office, and Campbell spoke to him for an hour and a half.

I say “spoke to him” not “spoke with him”, for Campbell’s idea of a conversation was to launch into a long monolog. Oddly enough, though, he was no bore. He was an inexhaustible fount of odd and exciting viewpoints, novel thoughts, and endless story ideas.

He had an unfailing eye for potential. He rejected my first story at once. He had said he would read it right off and had kept his word (very unusual in an editor) so that it was mailed back to me the very next day. However, he saw something in it, or in me, or both (Heaven only knows what it could have been at that stage) and encouraged me to continue writing. I could see him whenever I came in and he was unfailingly courteous and encouraging, even as he continued to reject my stories, until I had learned enough about writing (from actual experience at it and from listening to him) to begin selling.

I was not the only one. He talked to dozens of writers and slowly taught them that science fiction was not about adventure primarily, but about science. It was not about rescuing damsels in distress, but it was about solving problems. It was not about mad scientists, but about hard working thinkers. It was not by writers who had a facile hand with a cliché, but it was by writers who understood science and engineering and how those things worked and by whom they were conducted. In short, he found magazine science fiction childish, and he made it adult.

The wonder is that he was successful in doing so. It is hard not to view the world with cynical eyes and, to the cynic, improving the quality of an object and reducing its sensationalism, is the quickest road to bankruptcy one can imagine. Somehow, Campbell managed. As Astounding improved in quality, it also improved in general acceptance and in profitability.

The true test came in 1948. Pulp fiction had been fighting a losing battle during the 1940s. World War II had created a paper shortage and a combination of the draft and of war-work had reduced the number of writers. (Campbell’s other magazines, the wonderful Unknown, succumbed to this.) In addition, comic magazines had come into being, had proliferated unimaginably, and had begun to draw off younger readers delaying and, sometimes, totally aborting their eventual reading of pulp fiction.

In 1948, Street & Smith, which had been the most prominent and successful of all the pulp fiction publishers gave up and put an end to all their pulp magazines – all but one. Astounding Science Fiction, and only Astounding Science Fiction, continued. It was John Campbell who had made that possible. Had he not been there for ten years, improving Astounding and making it the phenomenon it was, the magazine might have ceased publication at that time and magazine science fiction might have been dead.

Who were the authors with whom Campbell worked? Some had already published stories in the pre-Campbell era, and Campbell could work with them, either because they were already thinking along Campbellesque lines or because they could do so once they were shown what it was that Campbell wanted. Outstanding among these were Jack Williamson, Clifford D. Simak and L. Sprague de Camp.

For the most part, though, Campbell found new writers. The July 1939, issue was the first issue that was truly marked by Campbell’s thinking and Campbell’s new authors, and it is usually considered as the first issue of “the Golden Age of science fiction”.

As its lead novelette, the issue had “Black Destroyer”, the first science fiction story written by A.E. van Vogt. It also contained “Trends” by Isaac Asimov, “Greater Than Gods” by C.L. Moore, and “The Moth” by Ross Rocklynne. All four of these authors have novellas in this collection. Van Vogt and Asimov are perfect examples of what are still referred to as “Campbell authors”. Moore and Rocklynne had published before, but Rocklynne became a Campbell author too.

In the very next issue, August 1939, there was a first story, “Life-Line”, by a new Campbell author named Robert A. Heinlein. He and van Vogt were the mainstays of Astounding for several years and were the science fiction “superstars” of the time. Indeed, Heinlein remained a superstar and the pre-eminent science fiction writer until his death a half-century later in 1988. We would certainly have included any of several Heinlein novellas in this book were it not for difficulties over permissions.

Another particularly great Campbell author who does not appear in this collection is Arthur C. Clarke, whose first science fiction story was “Loophole” which appeared in the April 1946, Astounding. Unfortunately, his 1940s output was almost entirely in the short story length.

In the September 1939, issue came “Ether Breather”, the first science fiction story of a new Campbell author named Theodore Sturgeon.

Among the earliest of the Campbell authors was Lester del Rey, whose first story, “The Faithful” appeared in the April 1938 Astounding. T.L. Sherred and A. Bertram Chandler were Campbell authors who first appeared later in the 1940s.

It is a true measure of the dominance of Campbell in the 1940s, that, of the ten stories in this collection, eight are from Astounding. The other two, by van Vogt (who is certainly a Campbell author just the same) and Fredric Brown, are from Thrilling Wonder Stories.

It is only fair to remember that not all great science fiction writers could write for Campbell. Some simply did not have, or did not want, the Campbell touch, and went their own way. Fredric Brown was one of these. Another – and perhaps the greatest of all science fiction writers who couldn’t or wouldn’t be a Campbell author – was Ray Bradbury.

In this collections of stories you will find yourself once again in the Golden Age of science fiction and the great days of John W. Campbell, Jr.

Asteroid No. 1007 came spinning relentlessly up.

Lieutenant Tony Crow’s eyes bulged. He released the choked U-bar frantically, and pounded on the auxiliary underjet controls. Up went the nose of the ship, and stars, weirdly splashed across the heavens, showed briefly.

Then the ship fell, hurling itself against the base of the mountain. Tony was thrown from the control chair. He smacked against the wall, grinning twistedly. He pushed against it with a heavily shod foot as the ship teetered over, rolled a bit, and then was still – still, save for the hiss of escaping air.

He dived for a locker, broke out a pressure suit, perspiration pearling his forehead. He was into the suit, buckling the helmet down, before the last of the air escaped. He stood there, pained dismay in his eyes. His roving glance rested on the wall calendar.

“Happy December!” he snarled.

Then he remembered. Johnny Braker was out there, with his two fellow outlaws. By now, they’d be running this way. All the more reason why Tony should capture them now. He’d need their ship.

He acted quickly, buckling on his helmet, working over the air lock. He expelled his breath in relief as it opened. Nerves humming, he went through, came to his feet, enclosed by the bleak soundlessness of a twenty-mile planetoid more than a hundred million miles removed from Earth.

To his left the mountain rose sharply. Good. Tony had wanted to put the ship down there anyway. He took one reluctant look at the ship. His face fell mournfully. The stern section was caved in and twisted so much it looked ridiculous. Well, that was that.

He quickly drew his Hampton and moved soundlessly around the mountain’s shoulder. He fell into a crouch as he saw the gleam of the outlaw ship, three hundred yards distant across a plain, hovering in the shadow thrown by an over-hanging ledge.

Then he saw the three figures leaping towards him across the plain. His Hampton came viciously up. There was a puff of rock to the front left of the little group. They froze.

Tony left his place of concealment, snapping his headset on.

“Stay where you are!” he bawled.

The reaction was unexpected. Braker’s voice came blasting back.

“The hell you say!”

A tiny crater came miraculously into being to Tony’s left. He swore, jumped behind his protection, came out a second later to send another projectile winging its way. One of the figures pitched forward, to move no more, the balloon rotundity of its suit suddenly lost. The other two turned tail, only to halt and hole up behind a boulder gracing the middle of the plain. They proceeded to pepper Tony’s retreat.

Tony shrank back against the mountainside, exasperated beyond measure. His glance, roving around, came to rest on a cave, a fault in the mountain that tapered out a hundred feet up.

He stared at the floor of the cave unbelievingly.

“I’ll be double-damned,” he muttered.

What he saw was a human skeleton.

He paled. His stomach suddenly heaved. Outrageous, haunting thoughts flicked through his consciousness. The skeleton was – horror!

And it had existed in the dim, unutterably distant past, before the asteroids, before the human race had come into existence!

The thoughts were gone, abruptly. Consciousness shuddered back. For a while, his face pasty white, his fingers trembling, he thought he was going to be sick. But he wasn’t. He stood there, staring. Memories! If he knew where they came from—His very mind revolted suddenly from probing deeper into a mystery that tore at the very roots of his sanity!

“It existed before the human race,” he whispered. “Then where did the skeleton come from?”

His lips curled. Illusion! Conquering his maddening revulsion, he approached the skeleton, knelt near it. It lay inside the cave. Colorless starlight did not allow him to see it as well as he might. Yet, he saw the gleam of gold on the long, tapering finger. Old yellow gold, untarnished by atmosphere; and inset with an emerald, with a flaw, a distinctive, ovular air bubble, showing through its murky transparency.

He moved backward, away from it, face set stubbornly. “Illusion,” he repeated

Chips of rock, flaked off the mountainside by the exploding bullets of a Hampton, completed the transformation. He risked stepping out, fired.

The shot struck the boulder, split it down the middle. The two halves parted. The outlaws ran, firing back to cover their hasty retreat. Tony waited until the fire lessened, then stepped out and sent a shot over their heads.

Sudden dismay showed in his eyes. The ledge overhanging the outlaw ship cracked – where the bullet had struck it.

“What the hell—” came Braker’s gasp. The two outlaws stopped stock-still.

The ledge came down, its ponderousness doubled by the absence of sound. Tony stumbled panting across the plain as the scene turned into a churning hell. The ship crumbled like clay. Another section of the ledge descended to bury the ship inextricably under a small mountain.

Tony Crow swore blisteringly. But ship or no ship, he still had a job to do. When the outlaws finally turned, they were looking into the menacing barrel of his Hampton.

“Get’em up,” he said impassively.

With studied insolence, Harry Jawbone Yates, the smaller of the two, raised his hands. A contemptuous sneer merely played over Braker’s unshaved face and went upward to his smoky eyes.

“Why should I put my hands up? We’re all pals, now – theoretically.” His natural hate for any form of the law showed in his eyes. “You sure pulled a prize play, copper. Chase us clear across space, and end up getting us in a jam it’s a hundred-to-one shot we’ll get out of.”

Tony held them transfixed with the Hampton, knowing what Braker meant. No ship would have reason to stop off on the twenty-mile mote in the sky that was Asteroid 1007.

He sighed, made a gesture. “Hamptons over here, boys. And be careful.” The weapons arced groundward. “Sorry. I was intending to use your ship to take us back. I won’t make another error like that one, though. Giving up this early in the game, for instance. Come here, Jawbone.”

Yates shrugged. He was blond, had pale, wide-set eyes. By nature, he was conscienceless. A broken jawbone, protruding at a sharp angle from his jawline, gave him his nickname.

He held out his wrists. “Put ’em on.” His voice was an effortless affair which did not go as low as it could; rather womanish, therefore. Braker was different. Strength, nerve, and audacity showed in every line of his heavy, compact body. If there was one thing that characterized him it was his violent desire to live. These were men with elastic codes of ethics. A few of their more unscrupulous activities had caught up with them.

Tony put cuffs over Yates’ wrist.

“Now you, Braker.”

“Damned if I do,” said Braker.

“Damned if you don’t,” said Tony. He waggled the Hampton, his normally genial eyes hardening slightly. “I mean it, Braker,” he said slowly.

Braker sneered and tossed his head. Then, as if resistance was below his present mood, he submitted.

He watched the cuffs click silently. “There isn’t a hundred-to-one chance, anyway,” he growled.

Tony jerked slightly, his eyes turned skyward. He chuckled.

“Well, what’s so funny?” Braker demanded.

“What you just said.” Tony pointed. “The hundred-to-one shot – there she is!”

Braker turned.

“Yeah,” he said. “Yeah. Damnation!”

A ship, glowing faintly in the starlight, hung above an escarpment that dropped to the valley floor. It had no visible support, and, indeed, there was no trace of the usual jets.

“Well, that’s an item!” Yates muttered.

“It is at that,” Tony agreed.

The ship moved. Rather, it simply disappeared, and next showed up a hundred feet away on the valley floor. A valve in the side of the cylindrical affair opened and a figure dropped out, stood looking at them.

A metallic voice said, “Are you the inhabitants or just people?”

The voice was agreeably flippant, and more agreeably feminine. Tony’s senses quickened.

“We’re people,” he explained. “See?” He flapped his arms like wings. He grinned. “However, before you showed up, we had made up our minds to be – inhabitants.”

“Oh. Stranded.” The voice was slightly chilly. “Well, that’s too bad. Come on inside. We’ll talk the whole thing over. Say, are those handcuffs?”

“Right.”

“Hm-m-m. Two outlaws – and a copper. Well, come on inside and meet the rest of us.”

An hour later, Tony, agreeably relaxed in a small lounge, was smoking his third cigarette, pressure suit off. Across the room was Braker and Yates. The girl, whose name, it developed, was Laurette, leaned against the door jamb, clad in jodhpurs and white silk blouse. She was blond and had clear deep-blue eyes. Her lips were pursed a little and she looked angry. Tony couldn’t keep his eyes off her.

Another man stood beside her. He was dark in complexion and looked as if he had a short temper. He was snapping the fingernails of two hands in a manner that showed characteristic impatience and nervousness. His name was Erle Masters.

An older man came into the room, fitting glasses over his eyes. He took a quick look around the room. Tony came to his feet.

Laurette said tonelessly, “Lieutenant, this is my father. Daddy, Lieutenant Tony Crow of the IPF. Those two are the outlaws I was telling you about.”

“Outlaws, eh? said Professor Overland. His voice seemed deep enough to count the separate vibrations. He rubbed at a stubbled jaw. “Well, that’s too bad. Just when we had the DeTosque strata 1007 fitting onto 70. And there were ample signs to show a definite dovetailing of apex 1007 into Morrell’s fourth crater on Ceres, which would have put 1007 near the surface, if not on it. If we could have followed those up without an interruption—”

“Don’t let this interrupt you,” Masters broke in. His nails clicked. “We’ll let these three sleep in the lounge. We can finish up the set of indications we’re working on now, and then get rid of them.”

Overland shook his graying head doubtfully. “It would be unthinkable to subject those two to cuffs for a full month.”

Masters said irritably, “We’ll give them a parole. Give them their temporary freedom if they agree to submit to handcuffs again when we land on Mars.”

Tony laughed softly. “Sorry. You can’t trust those two for five minutes, let alone a month.” He paused. “Under the circumstances, professor, I guess you realize I’ve got full power to enforce my request that you take us back to Mars. The primary concern of the government in a case like this would be placing these two in custody. I suggest if we get under way now, you can devote more time to your project.”

Overland said helplessly, “Of course. But it cuts off my chances of getting to the Christmas banquet at the university.” Disappointment showed in his weak eyes. “There’s a good chance they’ll give me Amos, I guess, but it’s already December third. Well, anyway, we’ll miss the snow.”

Laurette Overland said bitterly, “I wish we hadn’t landed on 1007. You’d have got along without us then, all right.”

Tony held her eyes gravely. “Perfectly, Miss Overland. Except that we would have been inhabitants. And, shortly, very, very dead ones.”

“So?” She glared.

Erle Masters grabbed the girl’s arm with a muttered word and led her out of the room.

Overland grasped Tony’s arm in a friendly squeeze, eyes twinkling. “Don’t mind them, son. If you or your charges need anything, you can use my cabin. But we’ll make Mars in forty-eight hours, seven or eight of it skimming through the Belt.”

Tony shook his head dazedly. “Forty-eight hours?”

Overland grinned. His teeth were slightly tobacco-stained. “That’s it. This is one of the new ships – the H-H drive. They zip along.”

“Oh! The Fitz-Gerald Contraction?”

Overland nodded absently and left. Tony stared after him. He was remembering something now – the skeleton.

Braker said indulgently, “What a laugh.”

Tony turned.

“What,” he asked patiently, “is a laugh?”

Braker thrust out long, heavy legs. He was playing idly with a gold ring on the third finger of his right hand.

“Oh,” he said carelessly, “a theory goes the rounds the asteroids used to be a planet. They’re not sure the theory is right, so they send a few bearded long faces out to trace down faults and strata and striations on one asteroid and link them up with others. The girl’s old man was just about to nail down 1007 and 70 and Ceres. Good for him. But what the hell! They prove the theory and the asteroids still play ring around the rosy and what have they got for their money?”

He absently played with his ring.

Tony as absently watched him turning it round and round on his finger. Something peculiar about—He jumped. His eyes bulged.

That ring! He leaped to his feet, away from it.

Braker and Yates looked at him strangely.

Braker came to his feet, brows contracting. “Say, copper, what ails you? You gone crazy? You look like a ghost.”

Tony’s heart began a fast, insistent pounding. Blood drummed against his temple. So he looked like a ghost? He laughed hoarsely. Was it imagination that suddenly stripped the flesh from Braker’s head and left nothing but – a skull?

“I’m not a ghost.” He chattered senselessly, still staring at the ring.

He closed his eyes tight, clenched his fists.

“He’s gone bats!” said Yates, incredulously.

“Bats! Absolutely bats!”

Tony opened his eyes, looked carefully at Braker, at Yates, at the tapestried walls of the lounge. Slowly, the tensity left him. Now, no matter what developed he would have to keep a hold on himself.

“I’m all right, Braker. Let me see that ring.” His voice was low, controlled, ominous.

“You take a fit?” Braker snapped suspiciously.

“I’m all right.” Tony deliberately took Braker’s cuffed hands into his own, looked at the gold band inset with the flawed emerald. Revulsion crawled in his stomach, yet he kept his eyes on the ring.

“Where’d you get the ring, Braker?” He kept his glance down.

“Why – ’29, I think it was; or ’28.” Braker’s tone was suddenly angry, resentful. He drew away. “What is this, anyway? I got it legal, and so what?”

“What I really wanted to know,” said Tony, “was if there was another ring like this one – ever. I hope not . . . I don’t know if I do. Damn it!”

“And I don’t know what you’re talking about,” snarled Braker. “I still think you’re bats. Hell, flawed emeralds are like fingerprints, never two alike. You know that yourself.”

Tony slowly nodded and stepped back. Then he lighted a cigarette, and let the smoke inclose him.

“You fellows stay here,” he said, and backed out and bolted the door behind him. He went heavily down the corridor, down a short flight of stairs, then down another short corridor.

He chose one of two doors, jerked it open. A half dozen packages slid from the shelves of what was evidently a closet. Then the other door opened. Tony staggered backward, losing his balance under the flood of packages. He bumped into Laurette Overland. She gasped and started to fall. Tony managed to twist around in time to grab her. They both fell anyway. Tony drew her to him on impulse and kissed her.

She twisted away from him, her face scarlet. Her palm came around, smashed into his face with all her considerable strength. She jumped to her feet, then the fury in her eyes died. Tony came erect, smarting under the blow.

“Sportsmanlike,” he snapped angrily.

“You’ve got a lot of nerve,” she said unsteadily. Her eyes went past him. “You clumsy fool. Help me get these packages back on the shelves before daddy or Erle come along. They’re Christmas presents, and if you broke any of the wrappings—Come on, can’t you help?”

Tony slowly hoisted a large carton labeled with a “Do Not Open Before Christmas” sticker, and shoved it onto the lower rickety shelf, where it stuck out, practically ready to fall again. She put the smaller packages on top to balance it.

She turned, seeming to meet his eyes with difficulty.

Finally she got out, “I’m sorry I hit you like that, lieutenant. I guess it was natural – your kissing me I mean.” She smiled faintly at Tony, who was ruefully rubbing his cheek. Then her composure abruptly returned. She straightened.

“If you’re looking for the door to the control room, that’s it.”

“I wanted to see your father,” Tony explained.

“You can’t see him now. He’s plotting our course. In fifteen minutes—” She let the sentence dangle. “Erle Masters can help you in a few minutes. He’s edging the ship out of the way of a polyhedron.”

“Polyhedron?”

“Many-sided asteroid. That’s the way we designate them.” She was being patronizing now.

“Well, of course. But I stick to plain triangles and spheres and cubes. A polyhedron is a sphere to me. I didn’t know we were on the way. Since when? I didn’t feel the acceleration.”

“Since ten minutes ago. And naturally there wouldn’t be any acceleration with an H-H drive. Well, if you want anything, you can talk to Erle.” She edged past him, went swinging up the corridor. Tony caught up with her.

“You can help me,” he said, voice edged. “Wil

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...