- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

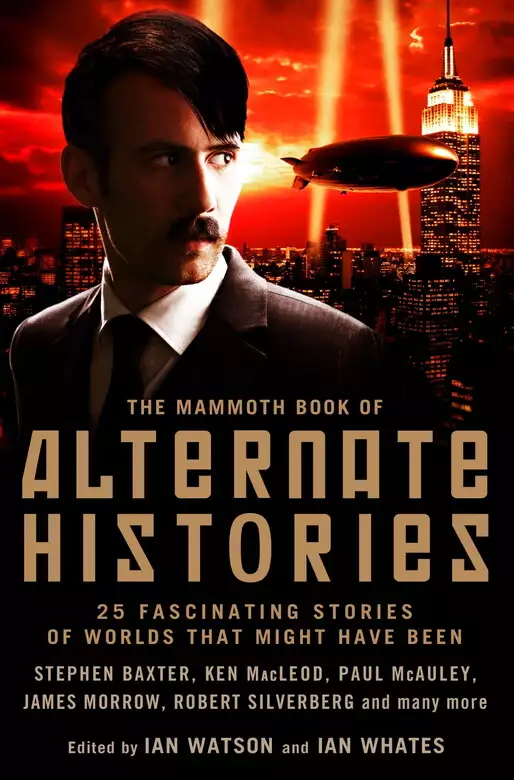

Every short story in this wonderfully varied collection has one thing in common: each features some alteration in history, some divergence from historical reality, which results in a world very different from the one we know today. As well as original stories specially commissioned from bestselling writers such as James Morrow, Stephen Baxter and Ken MacLeod, there are genre classics such as Kim Stanley Robinson's story of how World War II atomic bomber the Enola Gay, having crashed on a training flight, is replaced by the Lucky Strike with profoundly different consequences. Praise for the editors: 'Mr Watson wreaks havoc with what is accepted - and acceptable.' The Times 'One of Britain's consistently finest science fiction writers.' New Scientist

Release date: February 25, 2010

Publisher: Robinson

Print pages: 610

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mammoth Book of Alternate Histories

Ian Watson

INTRODUCTION by Ian Whates & Ian Watson, © 2010 Ian Whates & Ian Watson.

THE RAFT OF THE TITANIC by James Morrow, © 2010 James Morrow. Used by permission of the author.

SIDEWINDERS by Ken MacLeod, © 2010 Ken MacLeod. Used by permission of the author.

THE WANDERING CHRISTIAN by Eugene Byrne & Kim Newman, © 1991 Eugene Byrne & Kim Newman. Used by permission of the authors.

HUSH MY MOUTH by Suzette Hayden Elgin, © 1986 Suzette Hayden Elgin. Used by permission of the author.

A LETTER FROM THE POPE by Harry Harrison & Tom Shippey, © 1989 Harry Harrison & Tom Shippey. Used by permission of the authors.

SUCH A DEAL by Esther Friesner, © 1992 Esther Friesner. Used by permission of the author.

INK FROM THE NEW MOON by A. A. Attanasio, © 1992 A. A. Attanasio. Used by permission of the author.

DISPATCHES FROM THE REVOLUTION by Pat Cadigan, © 1991 Pat Cadigan. Used by permission of the author.

CATCH THAT ZEPPELIN by Fritz Leiber, © 1975. Used by permission of Richard Curtis Associates, Inc.

A VERY BRITISH HISTORY by Paul McAuley, © 2000 Paul McAuley. Used by permission of the author.

THE IMITATION GAME by Rudy Rucker, © 2008 Rudy Rucker. Used by permission of the author.

WEINACHTSABEND by Keith Roberts, © 1972 Keith Roberts. Used by permission of Owlswick Literary Agency.

THE LUCKY STRIKE by Kim Stanley Robinson, © 1984 Kim Stanley Robinson. Used by permission of the author.

HIS POWDER’D WIG, HIS CROWN OF THORNES by Marc Laidlaw, © 1989 Marc Laidlaw. Used by permission of the author.

RONCESVALLES by Judith Tarr, © 1989 Judith Tarr. Used by permission of the author.

THE ENGLISH MUTINY by Ian R. MacLeod, © 2008 Ian R. MacLeod. Used by permission of the author.

O ONE by Chris Roberson, © 2003 Chris Roberson. Used by permission of the author.

ISLANDS IN THE SEA by Harry Turtledove, © 1989 Harry Turtledove. Used by permission of the author.

LENIN IN ODESSA by George Zebrowski, © 1989 George Zebrowski. Used by permission of the author.

THE EINSTEIN GUN by Pierre Gévart, © 2000 as COMMENT LES CHOSES SE SONT VRAIMENT PASSÉES, Pierre Gévart. Used by permission of the author. English

translation © 2010 Sissy Pantelis & Ian Watson.

TALES FROM THE VENIA WOODS by Robert Silverberg, © 1989 Agberg, Ltd. Used by permission of Agberg, Ltd and the author.

MANASSAS, AGAIN by Gregory Benford, © 1991 Gregory Benford. Used by permission of the author.

THE SLEEPING SERPENT by Pamela Sargent, © 1992 Pamela Sargent. Used by permission of the author.

WAITING FOR THE OLYMPIANS by Frederik Pohl, © 1989 by Frederik Pohl. Used by permission of the author.

DARWIN ANATHEMA by Stephen Baxter, © 2010 Stephen Baxter. Used by permission of the author.

Introduction

“There is an infinitude of Pasts, all equally valid,” wrote André Maurois, the French novelist and biographer. “At each and every instant of Time,

however brief you suppose it, the line of events forks like the stem of a tree putting forth twin branches.” This is quoted in Virtual History: Alternatives and Counterfactuals, edited

by historian and political commentator Niall Ferguson. These days alternative history is almost respectable amongst historians, leading to such other recent well-received volumes of essays as

Robert Cowley’s What If? Military Historians Imagine What Might Have Been or Andrew Roberts’ What Might Have Been: Leading Historians on Twelve “What Ifs” of

History. Some other historians frown at counterfactuality; although, if the “Many Worlds” interpretation of Quantum Physics is correct, all possible alternatives might indeed occur

in a branching multiverse. What’s more, was our own world’s history in any sense inevitable, or even highly plausible, simply because it actually happened? Who, for instance, in 1975

might have imagined that a few years later a female British prime minister would be sending a nuclear-armed armada all the way to the South Atlantic in a quarrel about some remote islands full of

sheep? Who could have supposed that British counter-terrorism laws, provoked by planes flying into the World Trade Center, would be used for the first time bizarrely to seize the assets of a

mild-mannered Icelandic bank, on account of mortgages stupidly sold to poor house buyers in the United States?

Essays about What Might Have Been are already fascinating, but it has long been a delight of science fiction writers to put flesh upon the bones. Consequently, here you’ll find what might

have happened if the Roman Empire had never declined and fallen; how Islam might have triumphed much more widely; how the Native American Indians might have repelled the European invasion; how the

other Indians, of India, might have forged an empire in place of the British Empire; how the civilized Chinese might already have been ensconced in California when the uncouth Europeans first

arrived there; how the Pope might really have offended King Alfred of the burnt cakes; and much much more that has surely happened elsewhere (or elsewhen) in alternity, even if it

didn’t happen quite that way in our version of reality. You’ll find award-winning classics of the sub-genre nestling alongside equally worthy nuggets that might previously have escaped

your notice and more recent gems, including three splendid, brand-new stories by special invitees James Morrow, Stephen Baxter and Ken MacLeod. These feature the alternative truth about the

Titanic, the trial for heresy of Darwin’s bones along with one of his descendants, and a near-future Scotland that begins as far south as London.

Ian Watson and Ian Whates

James Morrow

15 April 1912

Lat. 40°25´ N, Long. 51°18´ W

The sea is calm tonight. Where does that come from? Some Oxbridge swot’s poem, I think, one of those cryptic things I had to read in tenth form – but the title

hasn’t stayed with me, and neither has the scribbler’s name. If you want a solid education in English letters, arrange to get born elsewhere than Walton-on-the-Hill. “The sea is

calm tonight.” I must ask our onboard littérateur, Mr Futrelle of Massachusetts. He will know.

We should have been picked up – what? – fourteen hours ago. Certainly no more than sixteen. Our Marconi men, Phillips and Bride, assure me that Captain Rostron of the

Carpathia acknowledged the Titanic’s CQD promptly, adding, “We are coming as quickly as possible and expect to be there within four hours.” Since the Ship of Dreams

sailed into the Valley of Death, sometime around 2.20 this morning, we have drifted perhaps fifteen miles to the southwest. Surely Rostron can infer our present position. So where the bloody hell

is he?

Now darkness is upon us once again. The mercury is falling. I scan the encircling horizon for the Carpathia’s lights, but I see only a cold black sky sown with a million apathetic

stars. In a minute I shall order Mr Lightoller to launch the last of our distress rockets, even as I ask Reverend Bateman to send up his next emergency prayer.

For better or worse, Captain Smith insisted on doing the honourable thing and going down with his ship. (That is, he insisted on doing the honourable thing and shooting himself, thereby

guaranteeing that his remains would go down with his ship.) His gesture has left me en passant in command of the present contraption. I suppose I should be grateful. At long last I have a

ship of my own, if you can call this jerry-built, jury-rigged raft a ship. Have the other castaways accepted me as their guardian and keeper? I can’t say for sure. Shortly after dawn

tomorrow, I shall address the entire company, clarifying that I am legally in charge and have a scheme for our deliverance, though that second assertion will require of the truth a certain

elasticity, as a scheme for our deliverance has not yet visited my imagination.

I count it a bloody miracle that we got so many souls safely off the foundering liner. The Lord and all His angels were surely watching over us. So far we have accumulated only nineteen corpses:

a dozen deaths during the transfer operation – shock, heart attacks, misadventure – and then another seven, shortly after sunrise, from hypothermia and exposure. Grim statistics, to be

sure, but far better than the thousand or so fatalities that would have occurred had we not embraced Mr Andrews’ audacious plan.

Foremost amongst my immediate obligations is to start keeping a record of our tribulations. So here I sit, pen in one hand, electric torch in the other. By maintaining a sort of captain’s

log, I might actually start to feel like a captain, though at the moment I feel like plain old Henry Tingle Wilde, the Scouser who never got out of Liverpool. The sea is calm tonight.

16 April 1912

Lat. 39°19´ N, Long. 51°40´ W

When I told the assembled company that, by every known maritime code, I am well and truly the supreme commander of this vessel, a strident voice rose in protest: Vasil

Plotcharsky from steerage, who called me “a bourgeois lackey in thrall to that imperialist monstrosity known as White Star Line.” (I’ll have to keep an eye on Plotcharsky. I

wonder how many other Bolsheviks the Titanic carried?) But on the whole my speech was well received. Hearing that I’d christened our raft the Ada, “after my late wife, who

died tragically two years ago”, my audience responded with respectful silence, then Father Byles piped up and said, so all could hear, “Right now that dear woman is looking down from

heaven, exhorting us not to lose faith.”

My policy concerning the nineteen bodies in the stern proved more controversial. A contingent of first-cabin survivors led by Colonel Astor insisted that we give them “an immediate

Christian burial at sea”, whereupon my first officer explained to the aristocrats that the corpses may ultimately have “their part to play in this drama”. Mr Lightoller’s

prediction occasioned horrified gasps and indignant snorts, but nobody moved to push these frigid assets overboard.

This afternoon I ordered a complete inventory, a good way to keep our company busy. Before floating away from the disaster site, we salvaged about a third of the buoyant containers Mr

Latimer’s stewards had tossed into the sea: wine casks, beer barrels, cheese crates, bread boxes, foot-lockers, duffel bags, toilet kits. Had there been a moon on Sunday night, we might have

recovered this jetsam in toto. Of course, had there been a moon, we might not have hit the iceberg in the first place.

The tally is heartening. Assuming that frugality rules aboard the Ada – and it will, so help me God – she probably has enough food and water to sustain her population, all

2,187 of us, for at least ten days. We have two functioning compasses, three brass sextants, four thermometers, one barometer, one anemometer, fishing tackle, sewing supplies, baling wire, and

twenty tarpaulins, not to mention the wood-fuelled Franklin stove Mr Lightoller managed to knock together from odd bits of metal.

Yesterday’s attempt to rig a sail was a fiasco, but this afternoon we had better luck, improvising a gracefully curving thirty-foot mast from the banister of the grand staircase, then

fitting it with a patchwork of velvet curtains, throw rugs, signal flags, men’s dinner jackets, and ladies’ skirts. My mind is clear, my strategy is certain, my course is set. We shall

tack towards warmer waters, lest we lose more souls to the demonic cold. If I never see another ice floe or North Atlantic growler in my life, it will be too soon.

18 April 1912

Lat. 37°11´ N, Long. 52°11´ W

Whilst everything is still vivid in my mind, I must set down the story of how the Ada came into being, starting with the collision. I felt the tremor about 11.40

p.m., and by midnight Mr Lightoller was in my cabin, telling me that the berg had sliced through at least five adjacent watertight compartments, possibly six. To the best of his knowledge, the ship

was in the last extremity, fated to go down at the head in a matter of hours.

After assigning Mr Moody to the bridge – one might as well put a sixth officer in charge, since the worst had already happened – Captain Smith sent word that the rest of us should

gather post-haste in the chartroom. By the time I arrived, at perhaps five minutes past midnight, Mr Andrews, who’d designed the Titanic, was already seated at the table, along with Mr

Bell, the chief engineer, Mr Hutchinson, the ship’s carpenter, and Dr O’Loughlin, our surgeon. Taking my place beside Mr Murdoch, who had not yet reconciled himself to the fact that my

last-minute posting as chief officer had bumped him down to first mate, I immediately apprehended that the ship was lost, so palpable was Captain Smith’s anxiety.

“Even as we speak, Phillips and Bride are on the job in the wireless shack, trying to raise the Californian, which can’t be more than an hour away,” the Old Man said.

“I am sorry to report that her Marconi operator has evidently shut off his rig for the night. However, we have every reason to believe that Captain Rostron of the Carpathia will be

here within four hours. If this were the tropics, we would simply put the entire company in life-belts, lower them over the side, and let them bob about waiting to be rescued. But this is the North

Atlantic, and the water is twenty-eight degrees Fahrenheit.”

“After a brief interval in that ghastly gazpacho, the average mortal will succumb to hypothermia,” said Mr Murdoch, who liked to lord it over us Scousers with fancy words such as

succumb and gazpacho. “Am I correct, Dr O’Loughlin?”

“A castaway who remains motionless in the water risks dying immediately of cardiac arrest,” the surgeon replied, nodding. “Alas, even the most robust athlete won’t

generate enough body heat to prevent his core temperature from plunging. Keep swimming, and you might last twenty minutes, probably no more than thirty.”

“Now I shall tell you the good news,” the Old Man said. “Mr Andrews has a plan, bold but feasible. Listen closely. Time is of the essence. The Titanic has at best one

hundred and fifty minutes to live.”

“The solution to this crisis is not to fill the life-boats to capacity and send them off in hopes of encountering the Carpathia, for that would leave over a thousand people stranded

on a sinking ship,” Mr Andrews insisted. “The solution, rather, is to keep every last soul out of the water until Captain Rostron arrives.”

“Mr Andrews has stated the central truth of our predicament,” Captain Smith said. “On this terrible night our enemy is not the ocean depths, for owing to the life-belts no one

– or almost no one – will drown. Nor is the local fauna our enemy, for sharks and rays rarely visit the middle of the North Atlantic in early spring. No, our enemy tonight is the

temperature of the water, pure and simple, full stop.”

“And how do you propose to obviate that implacable fact?” Mr Murdoch inquired. The next time he used the word obviate, I intended to sock him in the chops.

“We’re going to build an immense platform,” said Mr Andrews, unfurling a sheet of drafting paper on which he’d hastily sketched an object labelled Raft of the

Titanic. He secured the blueprint with ashtrays and, leaning across the table, squeezed the chief engineer’s knotted shoulder. “I designed it in collaboration with the estimable Mr

Bell” – he flashed our carpenter an amiable wink – “and the capable Mr Hutchinson.”

“Instead of loading anyone into our fourteen standard thirty-foot life-boats, we shall set aside one dozen, leave their tarps in place, and treat them as pontoons,” Mr Bell said.

“From an engineering perspective, this is a viable scheme, for each lifeboat is outfitted with copper buoyancy tanks.”

Mr Andrews set his open palms atop the blueprint, his eyes dancing with a peculiar fusion of desperation and ecstasy. “We shall deploy the twelve pontoons in a three-by-four grid, each

linked to its neighbours via horizontal stanchions spliced together from available wood. Our masts are useless – mostly steel – but we’re hauling tons of oak, teak, mahogany and

spruce.”

“With any luck, we can affix a twenty-five-foot stanchion between the stern of pontoon A and the bow of pontoon B,” Mr Hutchinson said, “another such bridge between the

amidships oarlock of A and the amidships oarlock of E, another between the stern of B and the bow of C, and so on.”

“Next we’ll cover the entire matrix with jettisoned lumber, securing the planks with nails and rope,” Mr Bell said. “The resulting raft will measure roughly one hundred

feet by two hundred, which technically allows each of our two thousand plus souls almost nine square feet, though in reality everyone will have to share accommodations with foodstuffs, water casks,

and survival gear, not to mention the dogs.”

“As you’ve doubtless noticed,” Mr Andrews said, “at this moment the North Atlantic is smooth as glass, a circumstance that contributed to our predicament – no wave

broke against the iceberg, so the lookouts spotted the bloody thing too late. I am proposing that we now turn this same placid sea to our advantage. My machine could never be assembled in high

swells, but tonight we’re working under conditions only slightly less ideal than those that obtain back at the Harland and Wolff shipyard.”

Captain Smith’s moustache and beard parted company, a great gulping inhalation, whereupon he delivered what was surely the most momentous speech of his career.

“Step one is for Mr Wilde and Mr Lightoller to muster the deck crew and have them launch all fourteen standard life-boats – forget the collapsibles and the cutters – each craft

to be rowed by two able-bodied seamen assisted where feasible by a quartermaster, boatswain, lookout, or master-at-arms. Through this operation we get our twelve pontoons in the water, along with

two roving assembly craft. The AB’s will forthwith moor the pontoons to the Titanic’s hull using davit ropes, keeping the lines in place until the raft is finished or the ship

sinks, whichever comes first. Understood?”

I nodded in assent, as did Mr Lightoller, even though I’d never heard a more demented idea in my life. Next the Old Man waved a scrap of paper at Mr Murdoch, the overeducated genius whose

navigational brilliance had torn a three-hundred-foot gash in our hull.

“A list from Purser McElroy identifying twenty carpenters, joiners, fitters, bricklayers, and blacksmiths – nine from the second-cabin decks, eleven from steerage,” Captain

Smith explained. “Your job is to muster these skilled workers on the boat deck, each man equipped with a mallet and nails from either his own baggage or Mr Hutchinson’s shop. For those

who don’t speak English, get Father Montvila and Father Peruschitz to act as interpreters. Lower the workers to the construction site using the electric cranes. Mr Andrews and Mr Hutchinson

will be building the machine on the leeward side.”

The Old Man rose and, shuffling to the far end of the table, rested an avuncular hand on his third officer’s epaulet.

“Mr Pitman, I am charging you with provisioning the raft. You will work with Mr Latimer in organizing his three hundred stewards into a special detail. Have them scour the ship for every

commodity a man might need were he to find himself stranded in the middle of the North Atlantic: water, wine, beer, cheese, meat, bread, coal, tools, sextants, compasses, small arms. The stewards

will load these items into buoyant coffers, setting them afloat near the construction site for later retrieval.”

Captain Smith continued to circumnavigate the table, pausing to clasp the shoulders of his fourth and fifth officers.

“Mr Boxhall and Mr Lowe, you will organize two teams of second-cabin volunteers, supplying each man with an appropriate wrecking or cutting implement. There are at least twenty emergency

fire-axes mounted in the companionways. You should also grab all the saws and sledges from the shop, plus hatchets, knives and cleavers from the galleys. Team A, under Mr Boxhall, will chop down

every last column, pillar, post and beam for the stanchions, tossing them to the construction crew, along with every bit of rope they can find, yards and yards of it, wire rope, Manila hemp,

clothesline, whatever you can steal from the winches, cranes, ladders, bells, laundry rooms and children’s swings. Meanwhile, Team B, commanded by Mr Lowe, will lay hold of twenty thousand

square feet of planking for the platform of the raft. Towards this end, Mr Lowe’s volunteers will pillage the promenade decks, dismantle the grand staircase, ravage the panels, and gather

together every last door, table and piano lid on board.”

Captain Smith resumed his circuit, stopping behind the chief engineer.

“Mr Bell, your assignment is at once the simplest and the most difficult. For as long as humanly possible, you will keep the steam flowing and the turbines spinning, so our crew and

passengers will enjoy heat and electricity whilst assembling Mr Andrews’s ark. Any questions, gentlemen?”

We had dozens of questions, of course, such as, “Have you taken leave of your senses, Captain?” and “Why the bloody hell did you drive us through an ice-field at twenty-two

knots?” and “What makes you imagine we can build this preposterous device in only two hours?” But these mysteries were irrelevant to the present crisis, so we kept silent, fired

off crisp salutes and set about our duties.

19 April 1912

Lat. 36°18´ N, Long. 52°48´ W

Still no sign of the Carpathia, but the mast holds true, the spar remains strong and the sail stays fat. Somehow, through no particular virtue of my own, I’ve

managed to get us out of iceberg country. The mercury hovers a full five degrees above freezing.

Yesterday Colonel Astor and Mr Guggenheim convinced Mr Andrews to relocate the Franklin stove from amidships to the forward section. Right now our first-cabin castaways are toasty enough, though

by this time tomorrow our coal supply will be exhausted. That said, I’m reasonably confident we’ll see no more deaths from hypothermia, not even in steerage. Optimism prevails aboard

the Ada. A cautious optimism, to be sure, optimism guarded by Cerberus himself and a cherub with a flaming sword, but optimism all the same.

I was right about Mr Futrelle knowing the source of “The sea is calm tonight.” It’s from “Dover Beach” by Matthew Arnold. Futrelle has the whole thing memorized.

Lord, what a depressing poem. “For the world, which seems to lie before us like a land of dreams, so various, so beautiful, so new, hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light, nor

certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain.” Tomorrow I may issue an order banning public poetry recitations aboard the Ada.

When the great ship Titanic went down, the world was neither various and beautiful, nor joyless and violent, but merely very busy. By forty minutes after midnight, against all odds, the

twelve pontoons were in the water and lashed to the davits. Mr Boxhall’s second-cabin volunteers forthwith delivered the first load of stanchions, even as Mr Lowe’s group supplied the

initial batch of decking material. For the next eighty minutes, the frigid air rang with the din of pounding hammers, the clang of furious axes, the whine of frantic saws and the squeal of ropes

locking planks to pontoons, the whole mad chorus interspersed with the rhythmic thumps of lumber being lowered to the construction team, the steady splash, splash, splash of provisions going into

the sea, and shouts affirming the logic of our labours: “Stay out of the drink!” “Only the cold can kill us!” “Twenty-eight degrees!” “Carpathia is

on the way!” It was all very British, though occasionally the Americans pitched in, and the emigrants proved reasonably diligent as well. I must admit, I can’t imagine any but the

English-speaking races constructing and equipping the Ada so efficiently. Possibly the Germans, an admirable people, though I fear their war-mongering Kaiser.

By 2.00 a.m. Captain Smith had successfully shot himself, three-fifths of the platform was nailed down, and the Titanic’s bridge lay beneath thirty feet of icy water. The stricken

liner listed horribly, nearly forty degrees, stern in the air, her triple screws, glazed with ice, lying naked against the vault of heaven. For my command post I’d selected the mesh of

guylines securing the dummy funnel, a vantage from which I now beheld a great mass of humanity jammed together on the boat deck: aristocrats, second-cabin passengers, emigrants, officers,

engineers, trimmers, stokers, greasers, stewards, stewardesses, musicians, barbers, chefs, cooks, bakers, waiters and scullions, the majority dressed in lifebelts and the warmest clothing they

could find. Each frightened man, woman and child held onto the rails and davits for dear life. The sea spilled over the tilted gunwales and rushed across the canted boards.

“The raft!” I screamed from my lofty promontory. “Hurry! Swim!” Soon the other officers – Murdoch, Lightoller, Pitman, Boxhall, Lowe, Moody – took up the cry.

“The raft! Hurry! Swim!” “The raft! Hurry! Swim!” “The raft! Hurry! Swim!”

And so they swam for it, or, rather, they splashed, thrashed, pounded, wheeled, kicked and paddled for it. Even the hundreds who spoke no English understood what was required. Heaven be praised,

within twelve minutes our entire company managed to migrate from the flooded deck of the Titanic to the sanctuary of Mr Andrews’s machine. Our stalwart ABs pulled scores of women and

children from the water, plus many elderly castaways, along with Colonel Astor’s Airedale, Mr Harper’s Pekingese, Mr Daniel’s French bulldog and six other canines. I was the last

to come aboard. Glancing around, I saw to my great distress that a dozen lifebelted bodies were not moving, the majority doubtless heart-attack victims, though perhaps a few people had got crushed

against the davits or trampled underfoot.

The survivors instinctively sorted themselves by station, with the emigrants gathering at the stern, the second-cabin castaways settling amidships, and our first-cabin passengers assuming their

rightful places forward. After cutting the mooring lines, the ABs took up the lifeboat oars and began to stroke furiously. By the grace of Dame Fortune and the hand of Divine Providence, the

Ada rode free of the wreck, so that when the great steamer finally snapped, breaking in two abaft the engine room, and began her vertical voyage to the bottom, we observed the whole

appalling spectacle from a safe distance.

22 April 1912

Lat. 33°42´ N, Long. 53°11´ W

We’ve been at sea a full week now. No Carpathia on the horizon yet, no Californian, no Olympia, no Baltic. Our communal mood is grim but

not despondent. Mr Hartley’s little band helps. I’ve forbidden them to play hymns, airs, ballads or any other wistful tunes. “It’s waltzes and rags or nothing,” I tell

him. Thanks to Wallace Hartley’s strings and Scott Joplin’s syncopations, we may survive this ordeal.

Although no one is hungry at the moment, I worry about our eventual nutritional needs. The supplies of beef, poultry and cheese hurled overboard by the stewards will soon be exhausted, and thus

far our efforts to harvest the sea have come to nothing. The spectre of thirst likewise looms. True, we still have six wine-casks in the first-cabin section, plus four amidships and three in

steerage, and we’ve also deployed scores of pots, pans, pails, kettles, washtubs and tierces all over the platform. But what if the rains come too late?

Our sail is unwieldy, the wind contrary, the current fickle, and yet we’re managing, slowly, ever so slowly, to beat our way towards the thirtieth parallel. The climate has grown bearable

– perhaps forty-five degrees by day, forty by night – but it’s still too cold, especially for the children and the elderly. Mr Lightoller’s Franklin stove has proven a boon

for those of us in the bow, and our second-cabin passengers have managed to build and sustain a small fire amidships, but our emigrants enjoy no such comforts. They huddle miserably aft, warming

each other as best they can. We must get farther south. My kingdom for a horse latitude.

The meat in steerage has thawed, though it evidently remains fresh, an effect of the cold air and the omnipresent brine. I shall soon be obligated to issue a difficult order. “Our choices

are clear,” I’ll tell the Ada’s company, “fortitude or refinement, nourishment or nicety, survival or finesse – and in each instance I’ve opted for the

former.” Messrs Lightoller, Pitman, Boxhall, Lowe and Moody share my sentiments. The only dissenter is Murdoch. My chief officer is useless to me. I would rather be sharing the bridge with

our Bolshevik, Plotcharsky, than that fusty Scotsman.

In my opinion an intraspecies diet need not automatically entail depravity. Ethical difficulties arise only when such cuisine is practiced in bad faith. During my one and only visit to the

Louvre, I became transfixed by Théodore Géricault’s Scène de naufrage “Scene of a Shipwreck”, that gruesome panorama of life aboard the notorious raft

by which the refugees from the stranded freighter Medusa sought to save themselves. As Monsieur Géricault so vi

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...