- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

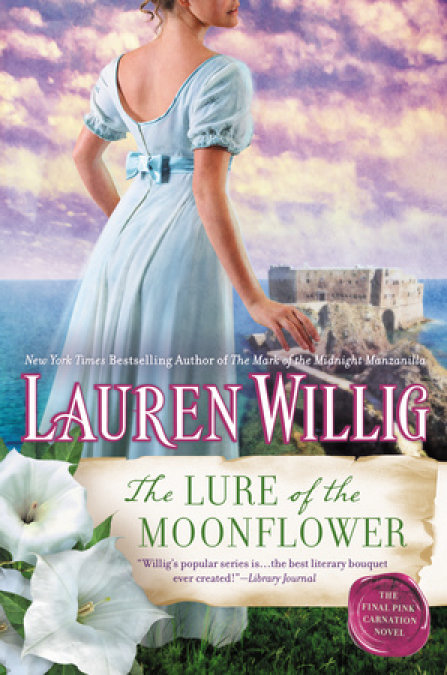

In the final Pink Carnation novel from the New York Times bestselling author of The Mark of the Midnight Manzanilla, Napoleon has occupied Lisbon, and Jane Wooliston, aka the Pink Carnation, teams up with a rogue agent to protect the escaped Queen of Portugal.

Portugal, December 1807. Jack Reid, the British agent known as the Moonflower (formerly the French agent known as the Moonflower), has been stationed in Portugal and is awaiting his new contact. He does not expect to be paired with a woman-especially not the legendary Pink Carnation.

All of Portugal believes that the royal family departed for Brazil just before the French troops marched into Lisbon. Only the English government knows that mad seventy-three-year-old Queen Maria was spirited away by a group of loyalists determined to rally a resistance. But as the French garrison scours the countryside, it's only a matter of time before she's found and taken.

It's up to Jane to find her first and ensure her safety. But she has no knowledge of Portugal or the language. Though she is loath to admit it, she needs the Moonflower. Operating alone has taught her to respect her own limitations. But she knows better than to show weakness around the Moonflower-an agent with a reputation for brilliance, a tendency toward insubordination, and a history of going rogue.

Release date: August 4, 2015

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 480

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Lure of the Moonflower

Lauren Willig

Prologue

Sussex, 2005

Reader, I married him.

Or, rather, I was in the process of marrying him, which is a much more complicated affair. Jane Eyre didn’t have to plan a wedding involving three transcontinental bridesmaids, two dysfunctional families, and one slightly battered stately home.

Of course, she did have to deal with that wife in the attic, so there you go.

There might occasionally be bats in Colin’s belfry, but there were no wives in his attic. I’d checked.

“Hey! Ellie!” My little sister drifted into the drawing room, where I was busily and profanely engaged in tying bows on the chairs that had been set up for the reception. Silk ribbon, I was learning, might be attractive, but it was also more slippery than a French spy in a Crisco factory. “Delivery for you! Is that supposed to look that way?”

“It’s a postmodern take on the classic bow,” I said, with as much dignity as I could muster. “Think . . . Foucault’s bow.”

Jillian cocked a hip. “Or you could just call it lopsided.”

“O, ye of little faith.” I abandoned my attempts at Martha Stewartry. The guests wouldn’t care if there were bows or not. They just wanted us to be happy. And an open bar. “You said there was a delivery? Please tell me it’s the port-a-loos.”

“There’s a perfectly good bathroom down the hall. If you want to, you know, wash off that thing.” Jillian gestured at the tectonic layers of mud that were beginning to crack on my face.

No, I hadn’t fallen in the garden. I had fallen prey to my oldest friend, Pammy, and her Big Box of Beauty Aids. Which appeared to involve highly priced purple-tinted garden mud.

“Not for me. For the reception,” I said patiently. Well, sort of patiently. My mud mask was beginning to itch.

I was pretty sure it wasn’t supposed to itch.

“Not unless it’s one for midgets,” said Jillian.

“Cutlery? A tent?” I followed Jillian down the hall, ticking off items, and rather wishing we’d thought to invest in item number one: a wedding planner.

’Twas the afternoon before my wedding, and all through Selwick Hall nothing was where it was supposed to be, not one thing at all. We had chosen to be married in Colin’s not-so-stately home, on the theory that if you pour enough champagne, no one will notice the cracks in the plaster or the faded bits in the upholstery. We were having the ceremony in the drawing room and the reception on the grounds, which had sounded romantic in theory.

Like many things that sounded romantic in theory, it was proving more difficult in fact. Right now I was awaiting the delivery of a tent, several cartloads of china, folding chairs, half a dozen port-a-loos, and Colin’s best man, who had inexplicably failed to arrive, although his explanation through the crackling cell phone connection had hinted at obstacles including pile-ups on the A23, an overturned lorry just out of London, and the sheeted dead rising and gibbering in the streets.

Translation: he’d overslept and was just now leaving.

My future mother-in-law, on the other hand, had arrived safe and sound, which just went to show that there were times when the universe didn’t have its priorities straight.

With twenty-four hours left to go, I was beginning to wonder whether I shouldn’t have taken my mother’s advice and just had the wedding in New York.

But it was Selwick Hall that had kind of, sort of brought us together. Or at least given us the opportunity to find each other, depending on how you preferred to look at it.

I hadn’t come to England for love. I’d crossed the pond in search of a spy. And if that makes me sound like an extra from a James Bond movie, it couldn’t be further from the truth. The spy I was looking for was long since out of commission. My hunting grounds weren’t grotty clubs or the glass-walled lair of a villain with a taste for seventies-style furnishings, but the archives of the British Library and the Public Records Office in Kew; my weapons, a few heavily underlined secondary sources and ARCHON, which might sound like the sort of acronym chosen by a criminal cartel, but was really the electronic search engine for manuscript sources in the UK. Plug in a name and—voilà!—it would locate that person’s papers. Letters, diaries, random ramblings, you name it.

There was one slight problem: To find the papers, you needed a name. Spies tend not to use their real names. Unless they’re Bond, James Bond. I’d always wondered why, with such a public profile, no one had succeeded in bumping him off between missions.

The Pink Carnation hadn’t made the same mistake. The spy who gave the French Ministry of Police headaches, who had caused Bonaparte to gnash his molars into early extraction, didn’t go by his real name. He was everywhere and nowhere, a pastel shadow in the night. Oh, people had speculated about the Carnation’s identity. Some argued that he wasn’t even English, but a Frenchman, cunningly pretending to be an Englishman playing a Frenchman. And if that isn’t enough to make you want to reach for a gin and tonic, I don’t know what is.

But I had one lead. Sort of. When you’re desperate, “sort of” starts looking pretty good. According to Carnation lore, the Carnation had his start in the League of the Purple Gentian, a spy unmasked fairly early in the game as one Lord Richard Selwick, younger son of the Marquess of Uppington.

So I’d done what any desperate grad student would do: I’d written to all the remaining descendants of Lord Richard Selwick, asking, pretty please, if anyone might happen to have any family papers lurking about in the attic or under a bed or tucked away among the lining of their sock drawers.

Did I mention that Colin just happened to be a descendant of that long-ago Lord Richard?

I found documents. I found love. I found the identity of the Pink Carnation. I didn’t quite find my doctorate, but that was another story. It was all ribbons and roses and happily-ever-afters, or at least it would be as long as the caterers catered, my mother didn’t kill my future mother-in-law before the ceremony, and all the bits and pieces made their way into place by roughly ten a.m. tomorrow.

I say ten a.m. because we were doing this the traditional way, morning suits and all. Everyone would be blotto by noon and hungover by sunset, but that seemed a small price to pay for the sight of Colin in a morning suit.

And yes, I may have watched Four Weddings and a Funeral one too many times.

“Delivery?” I reminded Jillian.

“It’s a box,” said Jillian informatively. “I signed for it for you.”

“Did it clink?” I asked plaintively. Booze. Booze would be good. Wedding guests would forgive lopsided bows and a missing best man as long as there was enough booze.

“See for yourself.” The deliverymen, in the way of deliverymen, had dropped the box smack in the middle of the hall, where it was currently impersonating a large speed bump.

Just what our wedding was missing: a do-it-yourself obstacle course.

Although, come to think of it . . .

I abandoned that tempting thought. Survival of the fittest is a principle best not applied to wedding guests. The person most likely to wipe out on the box was me, after a few gin and tonics too many at our rehearsal dinner.

I was not looking forward to the rehearsal dinner, that intimate occasion where one’s nearest and dearest can shower blessings on the impending nuptials. The big problem was that Colin’s nearest . . . Let’s just say they weren’t always dearest. There was enough bad blood there to give a vampire indigestion.

It was tough enough for Colin that his mother had run off with a younger man, a man only a decade older than Colin. Worse that she had done so while his father was dying, slowly and painfully, of cancer. But the real kicker? The younger man was Colin’s own cousin.

It got even more fun when you factored in Colin’s sister joining with his mother and stepfather in a coup against Colin the previous year, when they’d used the combined voting power of their shares in Selwick Hall to saddle Colin with a film company on the grounds of the Hall.

Never mind that Colin was the one who actually, you know, lived there.

For the most part, it had all been smoothed over. Colin and his sister were speaking again—just. And Colin and his stepfather had reached a tentative peace. As for Colin and his mother . . . that relationship made no more sense to me than it ever had.

The one saving grace in the mix—other than my groom himself, of course—was Colin’s aunt, Arabella Selwick-Alderly. I wasn’t sure whether it was her natural air of quiet dignity or the fact that she knew where all the bodies were buried, but either way, she was very effective at exerting a calming influence over feuding Selwicks.

I looked down at the box in the middle of the hall. It wasn’t a box so much as a trunk, the old-fashioned kind with a domed lid and brass bands designed to hold it together through squall, shipwreck, and clumsy customs officials. It looked as though it had been sent direct from Sir Arthur Wellesley, from his headquarters in Lisbon.

“Maybe it’s a wedding present?” said Jillian dubiously.

I looked from Jillian to the trunk, a smile breaking across my face. “That’s exactly what it is.”

Mrs. Selwick-Alderly had already given us a wedding present, and a rather nice one: a Georgian tea set, made of the sort of silver that bent the wrist when you tried to lift it. But there was no one else this could be from.

Unless the Duke of Wellington really had sent his campaign trunk from beyond the grave.

Ignoring the flaking mud on my face, I knelt down before the trunk. The box looked like it had been through several wars. The boards were warped with age and the elements; the brass tacks were crooked in parts and missing in others. But it had held together. Rather like the Selwick family.

It was also quite firmly locked. Again like the Selwick family.

I sat back on my haunches. “Was there a note? A key?”

Jillian held up her hands, palms up. “Don’t look at me. I’m just the messenger.”

“Eloise?” I could hear the slap of my mother’s Ferragamo pumps in the passage from the kitchen to the hall. Enter Mother, stage right, looking harried. “There’s a circus tent going up in your backyard.”

Poor Mom. She would have been much happier with a wedding at the Cosmopolitan Club, where all the arrangements simply happened, and no one had to figure out the placement of tents. My family has never gone in for camping. Or, for that matter, circuses.

I tried to sound reassuring. “That’s the marquee, Mom. It’s where we’re having the reception.”

My mother looked unconvinced. “Are you sure they didn’t rip off Ringling Brothers?”

“I don’t think they have Ringling Brothers here.”

My mother cast a dark glance over her shoulder. “Not anymore, they don’t.”

“Send in the clowns . . . ,” sang Jillian, not quite sotto voce. “Don’t bother. They’re here.”

I glowered at my sister over the domed lid of the Creepy Old Trunk. “Funny. Don’t you have a senior essay to write or something?”

“Not until next month.” Jillian smiled beatifically at me. “Until then, I’m all yours.”

“Lucky me,” I said dourly. Which, of course, really translated to I love you. It was, as Jillian would say, the way we rolled. We snarked because we loved. “Have I mentioned that I’m really glad you’re here?”

“I know,” said Jillian serenely. She gave me a one-armed hug that somehow managed to be equal parts comfort and condescension, as only a college senior knows how. “Nervous?”

“I can’t imagine why.” Drawing up a Selwick seating chart was like navigating a field full of land mines. And we all know how well that usually goes. Before the evening was over, someone was going to blow.

I just hoped it wouldn’t be me.

“Oy,” said someone from the doorway. His voice was rather muffled by the large, rectangular object on a dolly in front of him. “Where’d you want this?”

“Not in the house,” I said quickly. “If you just take the path around the back to the garden, and make a right past the tent . . .”

“I’ll show him,” said my mother, with her best martyr look. “You can go . . .” She gestured wordlessly at my face.

“Make yourself look a little less like Barney?” Jillian suggested.

“You used to love Barney,” said my mother reprovingly, and shooed the port-a-loo guys out the door.

“I was three,” said Jillian, to nobody in particular.

“Yup. I’m saving that for your wedding.”

“Hmm,” said Jillian, with a look of deep speculation that did not bode well for tomorrow’s maid-of-honor speech. “Where’s Colin?”

“Relative wrangling.” I’ll say this for the Selwicks: they’d all come out of the woodwork for our wedding, flying in from the far corners of the Earth, or stumbling in from the pub down the road, depending. There was a large Canadian delegation, as well as a bunch fresh off the plane from the UAE; there were Posies and Pollys and Sallys and enough hyphenated last names to make writing out place cards an exercise in wrist strain. The Posies and Pollys and Sallys were all very well. The main concern was that Colin not be left alone with his mother or stepfather for more than five minutes. I couldn’t even check in with him, since he’d left his cell phone with me, in case the tent people or the caterers called. “Oh, Lord. Would you—”

“On it,” said Jillian, and whisked out the door in search of her future brother-in-law. Pity the Selwick who got in her way.

There were all sorts of useful things I could be doing: tying bows on favors, chipping off my mud mask, promoting world peace, but instead I knelt beside the trunk.

The note was there, half stuck beneath the trunk, the creamy stationery grimed. I wrestled the envelope out from under the edge.

Eloise, it said, in letters that had never seen a ballpoint pen. The handwriting was as elegant as ever, but, I noticed with a pang, less certain than I had seen it before. Mrs. Selwick-Alderly had seemed ageless when I first met her, but she wasn’t ageless, any more than the rest of us, and the last two years had taken their toll.

With hands that weren’t entirely steady, I slid the note from the envelope.

My dear Eloise,

As you have no doubt guessed, this trunk was once the property of Miss Jane Wooliston. It traveled with her from Shropshire to Paris, from Paris to Venice, and from Venice to Lisbon.

Miss Jane Wooliston. I lowered the note, looking at the trunk with something like awe. I had spent the past three years tracing the steps of the spy known as the Pink Carnation, following her from Shropshire to France, from France to Ireland, from Ireland to England. But in all of that, I had never encountered anything that had belonged directly to her.

This was her trunk. She had used it in her travels, packed it with her disguises. It might, I thought with rising excitement, hold secret compartments, letters, clothing, clues to the Carnation’s personality.

And more than that. I had hit a wall in my research back in the fall. I could trace the Carnation to Sussex in 1805—but no further. In the spring of 1805, she had dissolved her league and gone deep undercover. So deep that none of the avenues I had explored had yielded any trace.

I had my guesses, of course. There were activities in Venice in the summer of 1807 that smacked of the Carnation’s style, especially as the episode also involved the French spy known as the Gardener, the Carnation’s colleague and nemesis. But I didn’t speak any Italian. I could have hired someone to go to the relevant archives for me, but . . .

By then, grad school and I had already parted ways.

Like all breakups, it gave me a pang to think of it. I knew intellectually that I’d made the right choice in jettisoning my academic career, but it was still hard not to feel nostalgic sometimes. I missed it. I didn’t want to go back—and I certainly didn’t want to be grading student papers—but I missed it all the same.

It was Colin who had suggested that I take my notes and turn them into something else entirely, spinning the Pink Carnation’s story from truth to fiction. So I’d dropped my footnotes into the garbage and spent a fevered seven months banging out the first episode in the Pink Carnation’s career, closing my eyes in the midst of a Cambridge winter and trying to imagine myself back in France in the spring in 1803, when a young Jane Wooliston and her cousin, Amy Balcourt, had arrived in France.

Oh, yes, and trying to plan my wedding.

Between wedding and writing, finding out what had happened to the Carnation after that break in 1805 had drifted into the background.

Until now.

I returned to Mrs. Selwick-Alderly’s note, but, maddeningly, she danced away from the main point.

The trunk was abandoned in Portugal in late 1807, at which point it disappeared from view for the better part of two centuries. Why it was abandoned and how it came into my possession are both tales for another day.

I could practically hear Mrs. Selwick-Alderly’s voice as I read, and see that spark of mischief in her eyes. As with all good fairy godmothers, one always had the sense that there was one last trick she was holding in reserve.

As long as she didn’t turn us all into mice, I was good with that.

It seems only fitting that the trunk end its journeys at Selwick Hall. I give it into your care, trusting that you shall do your utmost to preserve the trunk and the treasures it contains.

I remain, affectionately, Arabella Selwick-Alderly

There was nothing at all about a key. For that matter, I realized, swiping at the cracking mud on my face, although there was the usual brass plate on the front, there was no keyhole. It was as blank as a building without windows.

The trunk was like the Pink Carnation herself, a puzzle.

Like other trunks of its type, brass tacks marched in long lines down the sides and across the lid. Ordinarily they might have been used to spell out a monogram, but here there was none, just the workmanlike lines of tacks.

Two of which appeared to protrude slightly more than the others.

It would, I thought, be very like the Carnation to hide the solution in plain sight, something so simple that one wouldn’t expect it to be right. I reached out to press the tacks. . . .

And my jeans began vibrating.

No, no curse had been placed on the trunk. After my first nervous jump, I realized that it was Colin’s phone buzzing in my pocket. I wriggled it out of the pocket of my jeans, hoping fervently that it wasn’t the caterers with yet another last-minute polenta-related emergency. If it was, I might just have to go Napoleonic on someone’s nether regions. In translation: I would be politely dismayed in a rather chilly tone.

What can I say? I study the early nineteenth century, not the Middle Ages. Or rather, I had studied the early nineteenth century.

The display on the front said, RESTRICTED. Not the caterers, then.

“Hello?” I said quickly.

The voice on the other end said something staticky and incomprehensible.

“Hello?” I said again, the mud cracking around my mouth as I raised my voice. “Hello?”

Through the buzz, I heard only, “—Selwick.”

“This is his fiancée,” I said. “May I take a message?”

Wherever this guy was calling from, it sounded like he was underwater in a Harry Houdini cage. “Tell him . . . bring the box.”

“Is this Nick?” No connection was that bad by accident. And Colin’s best man was the prank-pulling kind. I knew only about half of what had gone on when they were at Oxford, and that half was more than enough. “Because if it is—”

A raspy voice interrupted me, sounding like a combination of a chronic cold and nails on sandpaper. “Tonight. Two o’clock. At the old abbey.”

Donwell Abbey, presumably. The ruins lay in the backyard of the current manor house, next door to Colin’s estate. If a twenty-minute drive over a bumpy road or an even longer walk along the more direct footpath counted as next door.

Yep, this was right up Nick’s alley. He’d just love to dress himself up as the Phantom Monk of Donwell Abbey, complete with hooded robe and phosphorescent paint, and drag Colin out at two in the morning on the night before his wedding. The real question was whether he could refrain from snickering long enough to remember to shout, “Boo!”

“Not funny.” I rolled my eyes. “If you’re at the services wasting time making prank calls—”

“It’s not Nick!” The voice on the other end forgot to rasp for a moment. It sounded vaguely familiar, but it definitely wasn’t Nick. Dropping back into film-noir mode, the voice went on. “Tell Selwick to follow instructions—or else. . . .”

“Or else?” I should have let it go to voice mail. But underneath my annoyance I could feel a little prickle of unease. There was something seriously disturbed about that voice. “Look, I’m going to—”

“Eloise?” It was a different voice, crackly with static and tension. A voice I knew. “Eloise—”

“Mrs. Selwick-Alderly?” She’d told me to call her Aunt Arabella, as Colin did, but in the tension of the moment, I forgot. “What on—”

But she was gone. “Tell him. Bring the box.”

And the line went dead.

Chapter One

Lisbon, 1807

The mood in Rossio Square was nasty.

The agent known as the Moonflower blended into the crowd, just one anonymous man among many, just another sullen face beneath the brim of a hat pulled down low against the December rain. The crowd grumbled and shifted as the Portuguese royal standard made its slow descent from the pinnacle of São Jorge Castle, but the six thousand French soldiers massed in the square put an effective stop to louder expressions of discontent. In the windows of the tall houses that framed the square, the Moonflower could see curtains twitch, as hostile eyes looked down on the display put on by the conqueror.

The French claimed to come as liberators, but the liberated didn’t seem any too happy about it.

As the royal standard disappeared from view and the tricolor rose triumphant above the square, the Moonflower heard a woman sob, and a man mutter something rather uncomplimentary about his new French overlords.

The Moonflower might have stayed to listen—listening, after all, was his job—but he had another task today.

He was here to meet his new contact.

That was all he had been told: Proceed to Rossio Square and await further instructions. He would know his contact by the code phrase “The eagle nests only once.”

Who in the hell came up with these lines?

Once, just once, he would appreciate a phrase that didn’t involve dogs barking at midnight or doves flying by day.

The message had given no hint as to the new agent’s identity; it never did. Names were dangerous in their line of work.

The Moonflower had gone by many names in his twenty-seven years.

Jaisal, his mother had called him, when she had called him anything at all. The French had called him Moonflower, just one of their many flower-named spies, a web of agents stretching from Madras to Calcutta, from London to Lyons. He’d counted himself lucky; he might as easily have been the Hydrangea. Moonflower, at least, had a certain ring to it. In Lisbon he was Alarico, a wastrel who tossed dice by the waterfront; in the Portuguese provinces he went by Rodrigo—Rodrigo the seller of baubles and trader of horses.

His father’s people knew him as Jack. Jack Reid, black sheep, turncoat, and renegade.

Jack turned up the collar of his jacket, surveying the scene, keeping an eye out for likely faces.

Might it be the dangerous-looking bravo with the knife he was using to pick his teeth?

No. He looked too much like a spy to be a spy. In Jack’s line of work, anonymity was key. Smoldering machismo and resentment tended to attract unwanted attention.

There was a great deal of smoldering in the crowd. Since the French had marched into Lisbon, two weeks ago, with a ragtag force that could scarcely have conquered a missionary society, they had proceeded to make themselves unpleasant, requisitioning houses, looting stores, demanding free drinks.

The people of Lisbon simmered and stewed. This lowering of the standard, this public exhibition of dominance, was all that was needed to place torch to tinder. Jack wouldn’t be surprised if there were riots before the day was out.

Riots, yes. Rebellion, no. For rebellion one needed not just a cause, but a leader, and that was exactly what they didn’t have right now. The Portuguese court had hopped on board the remaining ships of their fleet and scurried off to the Americas, well out of the way of danger, leaving their people to suffer the indignities of invasion.

Not that it was any of his business. Jack didn’t get into the rights and wrongs of it all, not these days. Not anymore. He was a hired gun, and it just so happened that the Brits paid, if not better than the French, at least more reliably.

There was a cluster of French officers in the square, standing behind General Junot. They did go in for flashy uniforms, these imperial officers. Flashy uniforms and even flashier women. The richly dressed women hanging off the arms of the officers were earning dark stares from the members of the crowd, stares and mutterings.

Some were local girls, making up to the conqueror. Others were undoubtedly French imports, like the woman who stood to the far left of the huddled group, her dark hair a mass of bunched curls beneath the brim of a bonnet from which pale purple feathers molted with carefree abandon. Her clothes were all that was currently à la mode in Paris, her pelisse elaborately frogged, the fingers of her gloves crammed with rings.

A well-paid courtesan, at the top of her trade.

But there was something about her that caught Jack’s eye. It wasn’t the flashing rings. He’d seen far grander jewels in his time. No. It was the aura of stillness about her. She stood with an easy elegance of carriage at odds with all her frills and fripperies, and it seemed that the nervous energy of the crowd eddied and ebbed around her without touching her in the slightest.

Her features had the classical elegance that was all the rage. High cheekbones. Porcelain pale skin, tinted delicately pink at the cheeks. Jack had been around enough to know that it wouldn’t take long for the ravages of her trade to begin to show. Those clear eyes would become shadowed; that pale skin would be replaced with white lead and other cosmetics in a desperate simulacrum of youth, a frantic attempt to catch and hold the affections of first one man and then another, until there was nothing left but the bottle—or the river.

Better, thought Jack grimly, to be a washerwoman or a fishwife, a tavern keeper or a maid. Those occupations might be hell on the hands, but the other was hell on the heart.

Not that it was any of his lookout.

The courtesan’s eyes met Jack’s across the crowd. Met and held. Ridiculous, of course. There was a square full of people between them, and he was just another rough rustic in a shapeless brown jacket.

But he could have sworn, for that moment, she was looking fully at him. Looking and sizing him up.

For what? He was hardly a likely protector for a French courtesan.

Go away, princess, Jack thought. There’s nothing here for you.

The French might hold Portugal, but not for long. Rumors were spinning through the crowd. The British

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...