- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

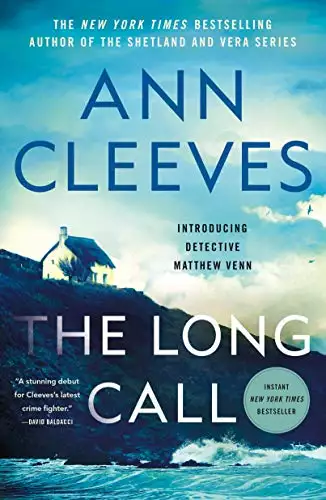

Now a major ITV series, The Long Call, adapted for television by screenwriter Kelly Jones and starring Ben Aldridge, who also reads this updated audiobook.

The Long Call is the No.1 bestselling first novel in the Two Rivers series from Sunday Times bestseller and creator of Vera and Shetland, Ann Cleeves.

In North Devon, where the rivers Taw and Torridge converge and run into the sea, Detective Matthew Venn stands outside the church as his father's funeral takes place. The day Matthew turned his back on the strict evangelical community in which he grew up, he lost his family too.

Now he's back, not just to mourn his father at a distance, but to take charge of his first major case in the Two Rivers region; a complex place not quite as idyllic as tourists suppose.

A body has been found on the beach near to Matthew's new home: a man with the tattoo of an albatross on his neck, stabbed to death.

Finding the killer is Venn’s only focus, and his team’s investigation will take him straight back into the community he left behind, and the deadly secrets that lurk there.

The next book in the series is The Heron's Cry.

This audiobook is an updated recording by Ben Aldridge.

Release date: September 3, 2019

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Long Call

Ann Cleeves

THE DAY THEY FOUND THE BODY on the shore, Matthew Venn was already haunted by thoughts of death and dying. He stood outside the North Devon Crematorium on the outskirts of Barnstaple, a bed of purple crocus spread like a pool at his feet, and he watched from a distance as the hearse carried his father to the chapel of rest. When the small group of mourners went inside, he moved closer. Nobody questioned his right to be there. He looked like a respectable man, a wearer of suits and sober ties, prematurely grey-haired and staid. Not a risktaker or a rule-breaker. Matthew thought he could have been the celebrant, arriving a little late for the service. Or a diffident mourner, sheepish and apologetic, with his soft skin and sad eyes. A stranger seeing him for the first time would expect sympathy and comfortable words. In reality, Matthew was angry, but he’d learned long ago how to hide his emotions.

He checked his feet to make sure that no flowers had been crushed, then walked between the headstones towards the path. The door to the chapel of rest had been left open – it was a warm day for so early in the year – and he could hear the service underway inside. The rich and passionate tone of a voice he’d have known anywhere: Dennis Salter, rousing his troops, persuading them that Andrew Venn was in heaven and they might be sad for themselves, but they should not be for their brother. Then came the heavy breathing of an electric organ and the slow and deliberate notes of a hymn that Matthew recognized but couldn’t name. He pictured Alice Wozencroft bent double over the keys, dressed entirely in black, hands like claws, a nose like a beak. As close to a crow as a woman could be. She’d been old even when he was a boy. Then he’d been a member of the Barum Brethren by birth and by commitment. His parents’ joy and hope for the future. Now he was cast out. This was his father’s funeral but he wasn’t welcome.

The hymn ground to a dreary close and he turned away. Soon the service would be over. His father’s coffin would slide behind the curtain and be turned to ash. The small group of mostly elderly women would gather in the sunshine to talk, then they might move on to his mother’s house for tea and home-baked cakes. Tiny glasses of sweet sherry. His name might be mentioned in passing. These people would understand that a bereaved woman would be missing her only son at a time like this, though, despite their sympathy, there would be no question that he should have been invited. It had been his choice to leave the Brethren. Matthew stood for a moment, thinking that lack of faith had little to do with choice. Doubt was a cancer that grew unbidden. He pushed away the guilt that still lurked somewhere in his body, physical, like toothache. The root of his anger. And the tattered remnant of belief that made him think that his father, the spirit or soul of his father, might be somewhere watching him, still disappointed in his son. Then he walked quickly back to his car.

The call came when he was nearly there. He leaned against the perimeter wall of the cemetery, his face to the light. It was Ross May, his colleague, his constable. Ross’s energy exhausted him. Matthew could feel it fizzing through the ether and into his ear. Ross was a pacer and a shouter, a pumper of iron. A member of the local running club and a rugby player. A team player except, it seemed, when he was at work.

‘Boss. Where are you?’

‘Out and about.’ Matthew was in no mood to discuss his whereabouts with Ross May.

‘Can you get back here? Someone’s found a body on the beach at Crow Point. Your neck of the woods.’

Matthew thought about that. ‘Accident?’ It happened, even in still weather. The tides there were treacherous. ‘Someone out in a small boat and washed ashore?’

‘No. The clothes are dry and they found him above the tideline. And there’s a stab wound.’ Matthew had only heard Ross this excited before in the run up to an important match.

‘Where are you?’

‘On my way. Jen’s with me. The news has only just come through. There’s a plod there who went out to the first call. Like you, HQ thought it would be an accident.’

Plod. Matthew bit back a criticism about the lack of respect for a colleague. You speak about a fellow officer like that and you’ll end up back in uniform yourself. This wasn’t the time. Matthew was still new to the team. He’d save the comment for the next appraisal. Besides, Ross was the DCI’s golden boy and it paid to go carefully. ‘I’ll meet you at the scene. Park at the end of the toll road and we’ll walk from there.’ The last thing they needed was a car stuck in the sand on the track to the point.

This early in the season there was little tourist traffic. In the middle of the summer it could take him more than an hour to drive home from the police station in Barnstaple, nose to tail behind big cars that blocked the narrow lanes and would have been ridiculous even in the London suburbs where they were registered. Today he sailed over the new bridge across the River Taw; upstream, he glimpsed Rock Park and the school where he’d been a student. He’d been a dreamer then, escaping into stories, losing himself on long, lonely walks. Imagining himself as a poet in the making. No one else had seen him that way. He’d been anonymous, one of those kids easily forgotten by teachers and the other pupils. When he’d turned up at a reunion a few years ago, he’d realized he’d had few real friends. He’d been too much of a conformer, too pious for his own good. His parents had told him he’d be a great preacher and he’d believed them.

He was jolted back to the present when he hit Braunton. A village when he’d been growing up but it felt like a small town now, not quite on the coast, but the gateway to it. The kids were coming out of school, and he tried to control his impatience at the lights in the village centre. Then a left turn towards the mouth of the estuary, where the Taw met the Torridge and flowed into the Atlantic. In the distance to the north stood the shoulder of Baggy Point, with the white block of a grand hotel just below the horizon. Monumental, but at the same time insubstantial because of the distance and the light.

This, as Ross had said, was home territory, but because he was approaching a crime scene, Matthew took in the details. The small industrial park, where they made surfboards and smart country clothes; the strip fields, brought back to life to feed incomers and posh grockles organic vegetables. The road narrowed; on each side a dry-stone wall, the stones laid edge on, with a hedge at the top. There were already catkins and soon there would be primroses. In sheltered parts of their garden they were already in bloom.

When Matthew hit the marsh, the sky widened and his mood lifted, just as it always did. If he still believed in the Almighty, he’d have thought his response to the space and the light a religious experience. It had been a wet winter and the ditches and the pools were full, pulling in gulls and wading birds. The flatland still had the colours of winter: grey, brown and olive. No sight of the sea here, but if he got out of the car, he’d be able to smell it, and in a storm he’d hear it too, the breakers on the long beach that ran for miles towards the village of Saunton.

He got to the toll road that led to the river and saw a uniformed officer standing there, and a patrol car, pulled onto the verge opposite the toll keeper’s cottage. The officer had been about to turn Matthew back, but he recognized him and lifted the barrier. Matthew drove through then stopped, pushed a button so his window was lowered.

‘Were you first on the scene?’

‘Yes, it came in as an accident.’ The man was young and still looked slightly queasy. Matthew didn’t ask if it was his first body; it would certainly be his first murder. ‘Your colleagues are already there. They sent me up to keep people away.’

‘Quite right. Who found him?’

‘A woman dog-walker. Lives in one of those new houses in Chivenor. She’s arranged for a neighbour to pick up her kid from school, but she wanted to be home for him. So I checked her ID, took her address and phone number and then I let her go. I hope that was okay.’

‘Perfect. No point having her hanging around.’ Matthew paused. ‘Are there any other cars down there?’

‘Not any more. An elderly couple turned up to their Volvo just as I was arriving. I got their names and addresses and took the car reg, but they’d been walking in the other direction and said they hadn’t seen anything. Then I still thought it was an accident so I didn’t really ask them much and let them drive off.’

‘I don’t know how long you’ll be here,’ Matthew said. ‘I’ll get someone to relieve you as soon as possible.’

‘No worries.’ The man nodded towards the cottage. ‘I had to explain to them what was happening and they’ve already been out to offer tea. They say they’ll keep an eye if I need to use their loo.’

‘I’ll be back to chat to them. Can you ask them to stick around until I get to them?’

‘Oh, they wouldn’t miss it for the world.’

Matthew nodded and drove on. He’d left the window down and now he could hear the surf on the beach and the cry of a herring gull, the sound naturalists named the long call, the cry which always sounded to him like an inarticulate howl of pain. These were the noises of home. There was a bend in the road and he could see the house. Their house. White and low and sheltered from the worst of the wind by a row of bent sycamores and hawthorns. A family home though they had no family yet. It was something they’d talked about and then left in the air. Perhaps they were both too selfish. They’d got the place cheap because it was prone to flooding. They’d never have been able to afford it otherwise. If there was a high tide and a westerly gale, the protective bank would be breached and the water from the Taw would flood the marsh. Then they’d be surrounded like an island. But the view and the space made it worth the risk.

He didn’t stop and open the gate to the garden, but drove on until he saw Ross’s car. Then he parked up and climbed the narrow line of dunes until he was looking down at the shore. Here, the river was wide and it was hard to tell where the Taw ended and the Atlantic began. Ahead of him the other North Devon river, the Torridge, fed into the sea at Instow. Crow Point jutted into the water from his side of the estuary, fragile now, eaten away by weather and water, and only accessible on foot. The sun was low, turning the sea to gold, throwing long shadows, and he squinted to make out the figures in the distance. Tiny Lowry figures, almost lost in the vast space of sand, sea and sky. He slid down the dune to the beach and walked towards them just below the tideline.

They stood at a distance from the body, waiting for the pathologist to arrive and the crime scene investigators to come with their protective tent. Matthew thought they were lucky that it was a still day and the man had been found on the dry sand away from the water. Exposed here, a gale would have the tent halfway to America and a high tide would have him washed away. There was no time pressure, apart from the walkers and the dog-owners who’d want their beach back. And the usual pressure of needing to inform relatives that a loved one had died, to get the investigation moving.

Jen and Ross had been looking out for him and Jen waved as soon as he hit the shore. The Puritan in Matthew disapproved of Jen, his sergeant. She’d had her kids too young, had bailed out of an abusive marriage and left behind her Northern roots to get a post with Devon and Cornwall Police. Now her kids were teens and she was enjoying the life that she’d missed out on in her twenties. Hard partying and hard drinking; if she’d been a man, you’d have called her predatory. She was red-haired and fiery. Fit and gorgeous and she liked her men the same way. But despite himself, Matthew admired her guts and her spirit. She brought fun and laughter to the office and she was the best detective he’d ever worked with.

‘So, what have we got?’

‘Hard to tell until we can get in to look at him properly.’ Ross turned to face the victim.

Matthew looked at the man. He lay on his back on the sand, and Matthew could see the stab wound in the chest, the bloodstained clothing.

‘How did anyone think this was an accident?’

‘When the woman found him, he was lying face down,’ Ross said. ‘The uniform turned him over.’ He rolled his eyes, but Matthew could understand how that might happen. From the back it would look like an accident, and community officers wouldn’t have much experience of dealing with unexplained death.

The man wore faded jeans, a short denim jacket over a black sweatshirt, boots that had seen better days, the tread gone, worn almost to a hole at the heel. His hair so covered in sand that it was hard to tell the colour. On his neck a tattoo of a bird. Matthew was no expert, but the bird had long wings. A gannet perhaps or an albatross, subtly drawn in shades of grey. The victim was slight, not an old man, Matthew thought, but beyond that it was impossible to guess from this distance. Ross was fidgeting like a hyperactive child. He found inactivity torture. Tough, Matthew thought. It’s about time you learned to live with it. There was something of the indulged schoolboy about Ross. It was the gelled hair and designer shirts, the inability to understand a different world view. He seemed a man of certainty. His marriage to Melanie, whom Jen had once described as the perfect fashion accessory, hadn’t changed him. If anything, Melanie’s admiration only confirmed his inflated opinion of himself.

‘I’m going to talk to the people who live in the toll keeper’s cottage. The gate’s automatic these days – you just throw money into the basket – but they’ll know the regulars and might have seen something unusual.’ Matthew had already turned to walk back along the shore to his car and threw the next comment over his shoulder. ‘Jen, you’re with me. Ross, you wait for the pathologist. Give me a shout when she arrives.’

Glancing to see the disappointment in Ross’s face, he felt a ridiculous, childish moment of glee.

Chapter Two

MAURICE BRADDICK WAS WORRIED about his daughter. The social worker at the day centre had come up with this notion to make Luce more independent. Let her get the bus back from town by herself. We’ll make sure she’s at the stop on time and you live at the end of the route. No danger of Lucy missing her stop. She can walk up the street to the house. She knows the way.

Maurice knew what that was all about. Lucy was thirty now and he was eighty. Getting on. Lucy had been a late child; a bit of a miracle, Maggie had said. But now Maggie was dead and he wasn’t as strong as he once was. He’d always thought he’d go first, because he’d been ten years older. It had never occurred to him that he’d be the one left behind, having to make decisions, holding things together. The social worker thought he wouldn’t be able to cope much longer with his lovely great lump of a daughter, because she had a learning disability. The social worker thought Maurice should be making arrangements for after he was gone. That might be sensible enough but he thought they were less concerned about Lucy’s independence than saving the council the taxi fare.

Every day since the new regime, he’d waited at his window to watch for his daughter walking up the lane. They lived in a little house on the edge of Lovacott village. He and Maggie had been there since they were married. It had been council then, but they’d bought it when the rules changed, thought it’d be a bit of an investment for Lucy. It was a semi at the end of a row of eight, curved around a patch of grass, where kids sometimes kicked a ball about. There was a long garden at the back looking out on a valley, with a view of Exmoor in the distance. These days, Maurice spent most of his time in the garden; he grew all their own veg and they had a run with half a dozen hens. He’d grown up on a farm and worked as a butcher in a shop in Barnstaple, knew about livestock dead and alive. Lucy wasn’t much into healthy eating, but she could sometimes be persuaded if she picked a few salad leaves herself or fetched the eggs. He paused for a moment to regret the passing of Barnstaple as he’d known it. Butchers’ Row had been full of butchers’ shops then. Now the little shops facing the pannier market were smart delis and places that sold pixie-shittery to the tourists. There wasn’t one real butcher left.

He was standing by the living room window because that had the best view of the road from the village. As soon as he glimpsed her coming around the corner he’d move away, so she wouldn’t know he was looking out for her, worrying. On the windowsill there was a photo of Lucy, one of his favourites. She was standing between two friends with her arms around them: Chrissie Shapland, who had Down’s Syndrome too, and young Rosa Holsworthy. They were all beaming straight into the camera. He looked outside again, but there was still no sign of Lucy walking down the road.

The afternoons it was raining Maurice was pleased, because that gave him the excuse to drive up and wait for the bus. Lucy didn’t like getting wet. If it was sunny like today, he waited. He’d always found it best to do what he was told and besides, he loved to see Lucy’s triumphant smile as she rounded the corner, her bag slung across her shoulder, proud because she’d made it home on her own. His mood lifted, just to see her. Today she was a little later than he would have expected. The bus should have been in twenty minutes ago and it was only a ten-minute walk to the house. He was just thinking that he’d walk up to the main road to check that all was well when there she was, dressed in the yellow dress that she loved so much, plump as a berry.

She gave him a wave as she approached but there was no wide smile. Perhaps the walk had become routine, even a bit of a chore. Luce had never been one for exercise. That was something else the social worker nagged about. We’ve noticed she’s been putting on a bit of weight, Mr Braddick. You should be careful what she’s eating, cut out all the fat and the sugar. No more chocolate! And what about taking her swimming? She loves it when they go from the centre. Or you could both get out for a walk when the weather’s better. Maurice thought it was easy for them. They didn’t have to deal with the sulks when she couldn’t get her way. And really, if she liked a piece of cake after her tea, what was the harm? He wasn’t one for walking much either and he’d never learned to swim.

He walked around to the front door to greet her as she came in. ‘All right, maid? I’ll put the kettle on, shall I, and you can tell me all about your day?’ Because she had a better social life than he did since he’d retired and he liked to hear her chatting about what she’d been up to. It made a change from the telly. Maggie had been the one who made friends and most of her pals from the village had stopped trying to get in touch with him. Some of them had turned up when she’d first died but he hadn’t known what to say to them. He’d just wanted to be on his own then; now, he thought, he might welcome their company.

Lucy pulled the strap of her bag over her head and took off the purple woollen cardigan she’d been wearing over the yellow dress.

‘The man wasn’t on the bus today.’

‘Oh?’ He was in the kitchen now, kettle switched on, not giving her his full attention. He opened the biscuit tin and set it on the table. ‘What man might that be?’

‘My friend. Most days he sits next to me. He makes me laugh.’ She’d followed Maurice through to the kitchen and stood leaning against the door frame. Her voice was troubled and now he did listen to her properly. He’d known, he thought, watching her walk towards the house, no smile, that something was wrong. ‘I waited when I got off the bus in case he came to see me there.’

‘Do you know him from the Woodyard?’ Lucy wasn’t the only person from the day centre who’d been encouraged to be more independent.

She shook her head. ‘He doesn’t go to the day centre. I’ve seen him before, though. On the bus. He tells me secrets.’ She frowned again. Her accent was pure North Devon, just like his. Warm and thick like the cream his mother used to make. Not always very clear to strangers, but he was tuned into it, tuned into her moods.

‘Where’s he from, maid?’ Maurice didn’t like this. Lucy was a trusting soul. Anyone who showed her kindness was a potential friend. Or a boyfriend. Maggie had tried to talk to her about it, about the people she could hug and the people she should keep at a bit of a distance, but he couldn’t find the right words.

‘I dunno.’ She looked away. ‘I just seen him around.’ Making it clear she didn’t want to answer the question. She could be stubborn as a mule when she chose.

Maurice turned back to face her. ‘Did he ever do anything? Say something to upset you?’

She shook her head and sat down heavily. ‘No!’ As if the idea was ridiculous. ‘He’s my friend.’ Her face was still red with the exertion of walking.

‘And he didn’t do anything he shouldn’t? He didn’t touch you?’ Maurice tried to keep the worry out of his voice. Luce picked up the tone of a person’s voice better than she understood the words.

‘No, Dad. He was always nice to me.’ And there was that wonderful smile again that lit up the room and made the world seem better.

Maurice felt a rush of relief. He didn’t know how he’d manage if someone hurt his daughter. He’d promised Maggie at the end that he’d always look after her. He had a brief picture of the overheated room in the hospice. Maggie, thin and bony with hair so fine he could see her pink scalp through it, gripping his arm. Fierce. Making him swear. She should have known him better than that, known he loved Lucy as much as she did. And perhaps she had known, because afterwards, she’d smiled and said sorry, she’d lifted his hand to her lips and kissed it. He chased the image away.

‘He gave me sweets,’ Lucy said. ‘Every day on the bus he gave me sweets.’

That made Maurice worried again. He thought he’d phone the social worker and tell her it wasn’t safe for Lucy to travel on her own on the bus. If he had to, he’d scrape together the money and pay for a taxi himself.

‘Where did he usually get off the bus, this man?’ Maurice set the mug of tea in front of Lucy. She liked it milky and weak.

‘Here,’ she said. ‘With me. That’s why I was late. I waited in case he’d got another bus and he’d come back to see me.’

‘Maybe you’ll have seen him in the village then.’

She reached out and took a biscuit from the tin. She nodded but Maurice could tell that he’d lost her attention. Now she was here with her dad and her tea and a biscuit, the man seemed forgotten. Any memory that might have troubled her had disappeared.

Copyright © 2019 by Ann Cleeves.

Excerpt from The Darkest Evening copyright © 2020 by Ann Cleeves

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...