- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

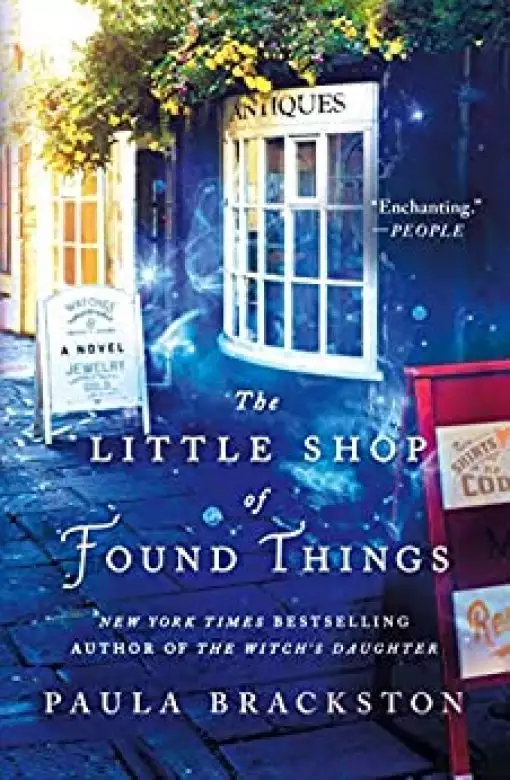

Paula Brackston, New York Times bestselling author of The Witch's Daughter, returns with her trademark blend of magic and romance guaranteed to enchant in the first audiobook in a new series.

An antique shop haunted by a ghost.

A silver treasure with an injustice in its story.

An adventure to the past she'll never forget.

Xanthe and her mother Flora leave London behind for a fresh start, taking over an antique shop in the historic town of Marlborough. Xanthe has always had an affinity with some of the antiques she finds. When she touches them, she can sense something of the past they come from and the stories they hold. When she has an intense connection to a beautiful silver chatelaine she has to know more.

It is while she's examining the chatelaine that she's transported back to the seventeenth century where it has its origins. She discovers there is an injustice in its history. The spirit that inhabits her new home confronts her and charges her with saving her daughter's life, threatening to take Flora's if she fails.

While Xanthe fights to save the girl amid the turbulent days of 1605, she meets architect Samuel Appleby. He may be the person who can help her succeed. He may also be the reason she can't bring herself to leave.

Release date: October 16, 2018

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Little Shop of Found Things

Paula Brackston

It is a commonly held belief that the most likely place to find a ghost is beneath a shadowy moon, among the ruins of a castle, or perhaps in an abandoned house where the living have fled leaving only spirits to drift from room to room. To believe so is to acknowledge but half a truth, for there is a connection with those passed over to be found much nearer home. Every soul that once trod this brutal earth leaves their imprint upon the things that mattered to them. The things that they held, the things that once echoed to the beat of their hearts. That heartbeat may yet be felt, faint but clear, transmitted through the fabric of those belongings, linking us to the dear one long gone through however many years have passed. Or at least, some may feel it. Some can hear its fluttering rhythm. Some can sense the life force that once thrummed through the golden metal, or gorgeous gem, or even the tattered remnant of a wedding gown. Some have the ability, the sensitivity, the gift to be able to connect to those lost ones through these precious objects.

Xanthe Westlake was such a person. The tall, young woman with the tumble of golden curls falling about her shoulders was possessed of that special gift. She had been barely eight years old when first it had shown itself. On that particular day she held a small silver teapot, turning it over in her hands, smiling brightly.

“You like that, Xanthe?” her mother, Flora, asked.

She nodded, running her fingers over the intricate filigree pattern on the cool silver.

“It’s a happy teapot,” she told her.

“Really? How do you know?”

“Because I can hear it singing,” she said, holding it up. “It was a present from a sailor to his daughter. He’d been away at sea for a long, long time, and when he came home he gave her this, and she made tea for them both. She loved her father very much.”

“Wow,” her mother said. “You got all that from the teapot?”

At the time, she must have thought such a proclamation merely the product of a youthful imagination, but later, when she inquired as to the teapot’s provenance and discovered that it had originated in Spain and been part of a sea captain’s estate, well, then she began to take notice of her child’s opinions. From that day, she started giving Xanthe things to hold to see if they would “sing” to her. And sometimes they did. And so her daughter would accompany her on buying trips to hunt for treasures. There was never any question but that she would go into the family business.

But a family business needs a family, and this one was smashed like a porcelain platter dropped upon a flagstoned floor.

When Xanthe arrived at the little antique shop that was to be her new home, many years after that first teapot, she was not conscious of being watched. As she helped her mother from the old black taxi that was her sole possession of note, she was concerned only with assisting Flora, who had yet to master the cobbles with her crutches. Xanthe was unaware, then, of the pale eyes that were upon her. Had she raised her own to look into the dusty bow window of the shop, she would not, of course, have seen her observer. Margaret Merton, a fine, well-dressed woman in her day, no longer cast a shadow nor reflected the light, for ghosts are insubstantial things.

It was high summer. The shop had been empty for several months, closed after the passing of Mr. Morris, the collectibles left to garner cobweb shrouds, and Margaret left to wander and wait. She held hope to her breast like a tiny bird which must be grasped tightly yet with such care, lest one crush it to nothing through fear of losing it. Hope was all she had. Of late, she had become aware of a change, and her spirit has roused itself from its fitful slumber. She sensed a reason for that hope to live on, to live more brightly. On that morning, in the month of July, she watched through the small windowpanes as the girl and her mother emerged from the bulky vehicle onto the sunlit, cobbled street. The older woman was perhaps the age Mistress Merton herself had been when she had met her end. Margaret felt a tightening in her chest as she watched daughter help mother, who walked with difficulty and with the aid of sticks. How many centuries had it been since Margaret had felt the touch of her own child’s hand upon hers? The pair looked up at the building, smiling, their excitement plain to see.

Flora Westlake took a key from her capacious shoulder bag and turned it in the lock. The shop door swung open, rattling into life the aged brass bell the previous owner had tolerated for a dozen years or more.

“Goodness!” Flora’s nose twitched at the smell of beeswax polish, dust, and stale air. “Looks like old Mr. Morris kept the place well stocked.”

“I’m not sure all of it qualifies for the word ‘stock,’” Xanthe replied, picking up a battered top hat that had not gleamed for decades. “How much did you say you paid for the contents, Mum?”

“Hardly anything at all, Xanthe, love,” she replied, waving one of her sticks as if to dismiss the worry.

Flora stood among her treasures and beamed. It was strange that it was not she who had the gift. Indeed, her daughter appeared largely unmoved by their new home, their new business, or the many, story-filled objects waiting for her touch. Even so, Margaret Merton saw the light that burned deep within the girl. Saw what it was and knew straight away that when the moment came, when those objects began to talk to her, Xanthe would listen. She would have no choice.

As the pair moved through the shop, Xanthe stepped so close to the ghost that her warmth seeped into that spirit. Naturally, the girl felt nothing of the specter with whom she had unwittingly elected to share her home. Xanthe’s sensitivity was to substantial things, through their tactile qualities. Margaret, having no substance other than that of a spirit, was undetectable to her. And so she would remain. Until she chose otherwise. Even so, that long-buried sense that humans have allowed to atrophy through lack of use; that instinct that warns of unseen dangers, could not help but respond to such a provocation as Mistress Merton’s restless soul presented. Xanthe paused, turning as if in answer to a distant calling of her name. Finding nothing, seeing no one, she shook off the sensation and resumed her inspection of the collectibles.

“There could be an awful lot of rubbish here,” she warned her mother, gazing at the jumble of things that filled every shelf and cabinet or sat in unstable heaps upon the floor.

“Well, most of it will probably have to go,” her mother agreed, “but there’s bound to be some of it worth salvaging. And we can do a bit of work on some of the furniture.” She nodded at a shabby chest of drawers which was sagging beneath bulging boxes, many filled with ancient books. “That would paint up nicely,” she said. “And that chair … and look here.” She moved forward to a box of sheet music and pulled out a selection. “There might be some material in here you could use, Xanthe, when you start singing again.”

“Mum … I really don’t want to even think about that right now.”

“OK, OK, just saying. Might be worth considering.” She turned to look at her daughter closely then. “You can’t just not sing, love. It’s part of you, you know that.”

Xanthe feigned interest in a rusty set of scales. When she gave no reply, Flora let the matter drop.

“Ooh, look through there,” Flora said, pointing with one of her crutches. “If I remember what the brochure said, Mr. Morris kept the second room just for mirrors.”

They went to investigate. Moments later they were standing in a narrow, windowless room that was filled wall to wall with mirrors. They were propped up against one another, leaning at all angles, some hung properly, others wedged in a corner or resting against a wall. Xanthe switched on the light. Several of the mirrors were in simple wooden frames, others were ornate, some plaster, some painted, some gilded. The two women stood in the middle of the room and saw themselves multiplied by dozens of reflections.

Margaret Merton stood at Xanthe’s shoulder, a singular presence without a single reflection.

Xanthe found the uncommon sight of herself, so repeated and replicated, an unsettling experience. These were not the distortions of a fairground hall of mirrors. The sense was more akin to Alice and her looking glass. Xanthe and her mother were truthfully mirrored, and yet, framed in so many ways, shown at so many angles, glimpsed in so many fogged and silvering surfaces, they looked oddly different. As if they were different people. They had their usual features and characteristics. There was Xanthe’s mass of dark blonde corkscrew curls. And those were unmistakably her customary vintage clothes. And she remained a good six inches taller than her mother, who still had a scrap of scarf tied in her fine, fluffy brown hair. Flora had crutches, Xanthe did not. The older woman’s feet were tiny and looked still smaller in her flat pumps. The black leather of Xanthe’s heavy Dr. Martens boots gleamed dully in the low light. For all the similarities, those multi-Floras and multi-Xanthes were somehow, crucially, not them.

“Bit of a thing with Mr. Morris, then, mirrors,” Xanthe said, rubbing a finger over one of the gilt frames. “Do you think he ever sold any or just collected them?”

“I don’t know the market around here yet,” Flora admitted. “But these’d sell in a week back in London.”

They exchanged uncomfortable glances at the mention of the city that was now firmly a part of their past.

The doorbell rang and Xanthe raised her eyebrows. “Our first customer, d’you reckon?”

Returning to the main part of the shop, she found the driver of the moving van.

“Didn’t want to risk getting stuck down that narrow street,” he told her. “We’re parked at the top end. Have to carry things from there.”

Xanthe followed him out. It was only a short walk to the point where the cobbled lane met the high street, but even so she was glad their possessions were few. It would take a number of trips to cart them to the shop via the slender thoroughfare. She allowed herself a moment’s pride that her beloved taxi with its superior design had made the tight turn required to navigate the route. The movers handed down boxes from the back of the van. There were cases of clothes and a small number of pieces of furniture taken from what had once been the family home. Flora had also demanded four boxes of stock from the auction house, despite her soon-to-be-ex-husband’s loud protestations. Xanthe considered her father had been deliberately obstructive, as if he wished to make Flora’s new life as difficult as possible. A point made all the more galling as it had been he who had wanted out of their marriage. Flora had been uninterested in shared household belongings, convincing herself she could replace everything when the settlement was finalized. That they were only insignificant things. That they did not matter. But Xanthe argued that they mattered a great deal, and that the reasons they were giving them up mattered, too. She admitted only to herself that not all of those reasons were the fault of her father. When it came to them having to find somewhere new and begin their lives afresh, Xanthe was painfully aware that she was, in her own way, equally to blame.

Carrying a heavy box marked KITCHEN, she made her way back down the tiny street. It was, in every respect, typical of the sort found in many English market towns, of which Marlborough was a fine example. The tarmac gave way to cobbles, smoothed under centuries of feet and hooves and wheels. The alleyway was barely 150 feet long, with small shops on either side. At the end, there was an archway under what had once been part of a coaching inn but was now apartments. It led only to some residents’ parking, so there was no through traffic. The shopkeepers had taken full advantage of this, putting out their wares on the cobbles, the tea shop to the right having set up tables and chairs. The little Wiltshire town was well known for its broad high street, its beautiful old buildings, and its antiques. Which was why, fifteen years after that astonishing Spanish teapot, Xanthe and Flora had chosen this place in which to set up shop. The charming town was a popular destination for treasure hunters and shoppers, with its Georgian redbrick town houses mellowed with age, mixed among black-and-white half-timbered shops and homes that were even older, some by hundreds of years. Twice a week a bustling market set up along the wide main street, colorful and tempting, and everywhere there was a feeling of affluent, happy, provincial life.

The shop itself was built of brick the color of fox fur, with a bloom of age softening that brightness. It had a bow window, the frames painted smart white to match that of the glass door with its many small panes. The shop sign had been covered up by the estate agent’s notice declaring it SOLD. Sold to Flora and Xanthe. Bought with every penny of their savings and a mortgage begged from a friendly broker. Until the divorce settlement came through they would be surviving largely on their wits, which meant the shop had to be restored, stocked, and opened as swiftly as was humanly possible. As Xanthe approached their new venture, she felt nervousness and excitement in equal measure. This was, for both of them, more than a business; it was a new life, and the modest flat above the shop was to be their new home. Xanthe recalled from the estate agent’s particulars that to the rear of the house lay a fair-size garden. As she followed the movers through the front door and saw again the overflowing shelves and tables, and took in the enormity of the task ahead of them, she accepted that it would be some time before she would be concerning herself with lawns and plants. There was work to be done in the shop, and plenty of it.

What she could not have known was that the ever watchful Mistress Merton had an entirely different plan for her.

* * *

That night Xanthe slept poorly, sensitive to the unfamiliar sounds of her new home, though unaware of the silent figure who kept vigil at the foot of her bed. It was the more mundane, earthly noises that disturbed her: the creaking and sighing of the building as it cooled in the night air; the clicking of the metal guttering as it contracted; the noises of the slumbering town drifting in through the open attic window. Both bedrooms were set into the roof of the house, hot in summer, cold in winter. Marlborough was a genteel and respectable place, and its night sounds were of an entirely different nature to the ceaseless thrum of London to which she had been accustomed. Here, there was only gentle midweek revelry, which quietened at what felt to her like a very early hour. In the dark depths of the night, she heard the occasional distant vehicle, the crying of a baby in another apartment, and the barking of a dog some way off. She dreamed no dreams as such, rather disconnected images passed through her sleeping mind. Pictures of the town and the shop and the mirrors with their endless reflections, seeming to offer so many possible futures.

When the dawn light eventually fell through the faded and flimsy curtains, she rose from her bed. Pulling the curtains open, she sat on the windowsill that formed a dusty seat from which to view the rooftops of Marlborough. Her room, being at the top of the house that had no loft space, wore the slope of the roof in its ceiling, and the window was cut in among the tiles. From this highpoint she could see across the uneven roofscape of shops and houses which was punctuated with church spires at either end of the high street, and faded into the distant, undulating countryside. Below, small birds were stirring in the walled garden, which consisted of a long swathe of unmowed lawn and a tangle of brambles, overgrown shrubs, and flowers. For a moment Xanthe considered sketching what she saw. She had always liked to draw and had developed a fair eye. It had proved useful in the trade, noting details of objects she was trying to authenticate, or taking down requirements from customers looking for something in particular. On that morning, however, the challenge of finding sketch pad and pencils among the packing cases was sufficient to deter her.

The day promised to be warm, and already the sun was touching everything with a soft golden glow. The town was beginning to wake up, and she could discern the rattle of shop shutters being raised. Pulling a fluffy jumper over her nightdress she descended the stairs barefoot. She loved to feel the ground under her bare feet and could not abide heels. When she did put something on her feet it was invariably her preferred tough boots, heavy and protective. She had never owned a pair of slippers. Not wanting to disturb Flora, she moved as quietly as she was able, but every stair and floorboard seemed to want to protest loudly at her treading upon it. The narrow stairs from the attic floor led down through the rest of the flat with kitchen, bathroom, and sitting room, and then widened to descend to the ground floor. The smell of old furniture, vintage leather, and antique objects of all shapes and sizes was as natural to Xanthe as the aroma of home cooking. She had been raised among such things. She did not see them as castoffs or the belongings of the dead as some people might. To her they were mementos, relics, heirlooms. Each of them held memories of past lives and loves. Held stories. And if she was fortunate, if she found the right pieces, they would share those stories with her.

The stairs turned down into a little hallway, to the rear of which was a room with a bench and sink. It was clear this was where Mr. Morris had worked on restorations and repairs. It was possible to get to the garden through a door at the far end of the hallway. The first room on her left was the one that housed the mirrors, and then the passageway opened out into the main part of the shop. Xanthe wandered into the shop and stood at its center, trying to make sense of the muddle. In the half-light of the early morning, everything had taken on a slightly blurred look, with softened edges and muted colors. The business, contents, and building had been sold after Mr. Morris’s death, and to judge by the dust, no one had touched anything since his passing. There was a sense of everything having been left just as it must have been when he was still running the shop. As Xanthe browsed through the stock, she was alert, as always, to the possibility of something special. She could not look through such a collection of antique pieces without hoping for a connection, for something with a story to tell. Her senses strained in the way a person listens hard for a familiar voice among the babble of chatter in a crowded room. There was a fair amount of china, including one or two pleasant Wedgwood plates; a good deal of “brown” furniture, mostly occasional tables, nothing spectacular; lots of boxes of old books; a cabinet of mostly Victorian jewelry; a stand of walking sticks and gentlemen’s umbrellas; in short, lots of things that were nice enough, but nothing that stood out. And as yet, nothing that sang. She pulled books at random from an overstuffed box. There were one or two on local history, another entitled Spinners. Xanthe knew the history of crafts could be popular, so she set the books aside in a pile to keep. They could be used to show off one of the better bookcases, if nothing else. There were paper bags, tissue paper, and sticking tape on the Edwardian desk that served as a counter. There was no till. Opening one of the heavy drawers, she found a small metal box. The key was in the lock. Inside were a few five-pound notes and a handful of change. Xanthe moved her attention to the ledger underneath it. Turning to the last entry, she could see Mr. Morris had ceased trading on the second Thursday in May, a little under three months earlier. It felt like an intrusion, reading his spidery handwriting, as if she were looking over his shoulder as he wrote down the sales for that day. They were few and paltry. If the new shop was to succeed, changes would have to be made, and the first of those was surely the finding of original, tantalizing, and irresistible stock.

“Xanthe?” Flora called down the stairs. “I’ve got the kettle on. Come and have breakfast.”

It appeared Xanthe was not alone in finding it difficult to sleep. As she left the main room of the shop to join her mother for breakfast, Margaret Merton watched her go. Out of a habit long fallen into uselessness, she smoothed the phantom fabric of her skirts with her fine, long-fingered hands. This girl’s inclination to dress for comfort and her own peculiar style rather than modesty and elegance were at odds with Margaret’s own preferences. As a young woman she had been beautiful and slender. A prize contested by wealthy and powerful suitors. It had been her misfortune to choose one not, ultimately, powerful enough to save her. As a married woman she had become well-respected and known for her grace and her wit. She could never have imagined wandering a house in a state of near undress, her hair disheveled, her feet bare as Xanthe’s were. And yet, this wild girl, this person so lacking in the qualities Margaret had striven to install in her own dear daughter, she was to be her godsend. Her hope personified. Her daughter’s salvation. For she knew now what had woken her from her incomplete sleep. She knew what it was that had caused her to stir to action, to witness the progress of the newcomer. She had seen it, clear as anything could be, that object, that thing on which a greater value had been placed than the life of her own child. It had returned to the place where it had once played such a vital part in her daughter’s life. It was closer now than it had ever been to Mistress Merton, and it lay in the path of this untamed girl, waiting.

The kitchen was no less chaotic than the shop, but here the clutter was caused by packing cases rather than old stock. Xanthe found Flora digging deep in a crate, in search of mugs.

“I’ve found coffee but we’ll have to have it black,” she said. “Breakfast is over there.”

Xanthe sat at the worn pine table. “Shortbread biscuits, cheese triangles, and marmalade?” she asked, examining the few edible things among the scrunched-up newspaper and piles of plates.

“You’ll have to spread it with a spoon. The knives seem to have gone missing. I expect they’ll turn up,” she said, turning off the gas beneath the kettle.

Flora was a woman of many talents, but cooking was not listed among them. It was not that she was unable to do it, simply that she detested supermarkets and was always far too engrossed in her antiques to remember to shop for food. This had led to her becoming more of an inventor than a cook, having to create meals out of the strangest combinations of ingredients. Xanthe had been brought up to expect the unexpected when it came to dinner, and as a result could not be perturbed by the most curious concoctions. Even so, this particular combination was new.

As they ate their crumbly breakfast and sipped the bitter coffee, they made their plan for the day. Flora had arranged their arrival to coincide with a local antiques sale.

“Perfect timing,” she insisted. “We can get over there early, seeing as we’re both up. Have a good poke around before the auction gets underway.”

“Some people might have begun by sorting out all the stock that’s here before running off to buy more,” Xanthe pointed out, rescuing a blob of marmalade from the front of her jumper.

“You can hardly accuse me of running anywhere,” she laughed.

Xanthe grinned, as ever humbled by her mother’s ability to laugh off her pain and disablement. More than eight years had passed since her diagnosis of a cruelly painful form of arthritis and still her humor, her love of life, her determination, remained undiminished.

“You know what I mean,” Xanthe said. “There’s a load of stuff to be gone through, never mind the unpacking and generally getting the flat organized.”

“Oh, don’t worry about all that. I find those sorts of things usually take care of themselves. I don’t want to waste time on the flat now. We need to get the business up and running, Xanthe. That has to be our priority.”

“Yes, but we do have to live here, too. You know, properly live, not just exist in heaps of craziness,” Xanthe reminded her, waving at the eye-high stacks of boxes and pointedly spreading more cheese with a spoon.

“And so we shall. And it will be lovely. Just you and me. We don’t need anyone else.” She sounded bright enough, but Xanthe knew her too well. She could hear the catch in her voice every time she came close to mentioning her husband. Flora glanced at Xanthe, conscious of the fact that she too could be hurt by memories. After all, they both knew what it was like to be betrayed by someone they loved. “Besides,” she said, steering the conversation back onto safer ground, “we’ve a marvelous sale to go to. By all accounts something special. Not to be missed.” She fished in her bag and pulled out the catalog, waving it beneath her daughter’s nose. “China, silver, jewelry, oodles of lovely things. Have a look.”

The front cover declared this to be a SALE OF FINE ANTIQUES AND COLLECTIBLES taking place at the beautiful Great Chalfield Manor. Xanthe always felt a tickle of excitement when browsing through a sale catalog, but this time, as she took the glossy booklet from her mother, she felt something else. Something stronger. She was on the point of opening it, ready to scour the pages to see if she could identify what it was that she was connecting with, but she found herself hesitating. In all those years of having things sing to her, all those dozens of special objects, she had never reacted to a mere picture before. For some reason she could not quite fathom, she didn’t wish to “meet” whatever it was at such a remove, seeing its captured image and a few basic lines of description. She felt compelled to wait. To come face-to-face with it. To hear it call to her. To discover it and touch it. That was the way it should be.

“Xanthe?” Flora had noticed her reluctance to open the catalog.

“Actually, I’ll read it when we get there,” she said, getting up from the table. “Think I’ll go and see if I can get the shower to work. Wash off some of this dust.”

“Well, don’t be long. It’s a twenty-minute drive from here. We need to get going if we are to steal a march on the other buyers. And anyway, I want to start hunting for treasure!”

Xanthe hurried to get ready, spurred on by the thought that today she would find something truly special. Or, more accurately, today something special would find her.

Copyright © 2018 by Paula Brackston

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...