- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

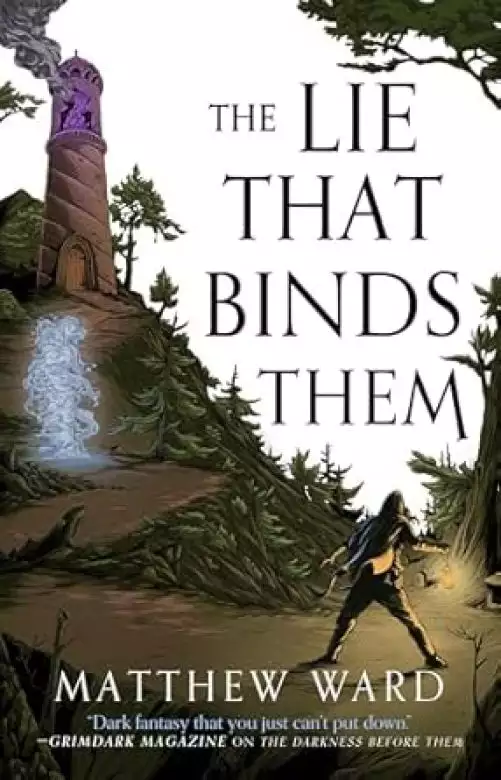

Set in a world of ancient myth and dangerous magic, The Lie That Binds Them is the heart-pounding conclusion to Matthew Ward's Soulfire Saga, where a thief dares to seek vengeance against an immortal king—and finds herself on the path to war.

The kingdom of Khalad is ruled by a new and brutal despot and its rebels scattered across its vast lands. With folk hero Vallant missing, Kat is now the leader of the rebellion.

When an assassination attempt rattles the kingdom, Kat turns to a powerful new ally for help. The cost of victory will be high, but time is running out to save Khalad.

Release date: April 15, 2025

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 576

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Lie That Binds Them

Matthew Ward

Hope had always been the lie binding them together.

And as the streets beyond Manniqa Station burned, all Kat could think was that Vallant would have handled things better.

Beyond the soot-smeared glass of the station’s arched roof, eerie wails and bright flashes against the rising smoke proved that a handful of Tyzanta’s shrieker cannon batteries fought on. A redcloak dhow, black sails silhouetted against the setting sun and wreathed in vapour from the ruptured buoyancy tanks along its scorched hull, listed towards the lower city. Spars snapped and rigging thrashed as its starboard flank scraped a warehouse’s third storey. Blackened rubble rained down on the station roof. Steel buckled. Glass crazed and disintegrated into glittering shards. Screams rang out along a crowded platform thick with the acrid stench of smoke and terror.

Kat stalked aft along the railrunner, jumping from one carriage rooftop to the next through the engine’s billowing steam.

“Keep them moving!”

She shouted to be heard over the platform’s sobbing, jostling rush of men, women and children. A crowd fed by the stream of refugees flowing past the makeshift barricade stretching from the stationmaster’s office to the cargo exchange at the station gate.

The black-robed custodians labouring to keep order knew full well that time was running out, but speaking the words aloud held Kat’s feeling of impotence at bay. It drew eyes to what she hoped was her calm, confident demeanour. Now more than ever she needed to live up to the simple black uniform and silver thread that marked her out as Tyzanta’s governor.

The last of the city’s great and good – those with the tetrams to buy passage on merchant skyships – had fled a week before, when the black sails of the Eternity Queen’s war dhows had thickened on the western horizon. Most had headed east to Qersal even before that, when the shipyards at Azran had fallen and Naxos’ ruling council had sued for peace. The sole remaining railrunner was for those too poor to make their own escape, or too loyal to abandon the failing dream. Twenty carriages and wagons scavenged from sidings across the city, most of them fit for the scrapper’s yard. All of them already approaching capacity. And still the platform seethed with hundreds of lost souls fleeing the advancing redcloaks.

Many thousands more didn’t want to leave. Too many welcomed the coming of the Eternity Queen, or were at least ambivalent to whom they paid their protection levies. They didn’t know what Kat knew. About the Eternity Queen. About the Kingdom of Khalad. About the three-faced goddess Nyssa. The lies at Khalad’s heart that promised the bleakest of futures.

As Kat approached the rearmost carriage a shadow rushed overhead. Shading her eyes, she craned her neck to see a second, smaller skyship augur in on the beleaguered dhow. Its cannons spat invisible flame, blasting blackened timber from the redcloak vessel’s portside hull. Sadia’s Revenge, one of only three skyships left in the city from a fleet now scattered to the winds.

The dhow’s portside buoyancy tanks gave way with an aching sigh that set the station’s surviving roof panes clattering. Lateen sail ablaze, it plunged, lost amongst the blocky adobe risings of factories and warehouses. Sadia’s Revenge burst through its trailing smoke, filthy canvas blossoming on outrigger and spar to plunder every scrap of wind. Armoured keel plates scraped across roof tiles. A trailing spar set a weathercock spinning. And then the skyship soared away, ushered on by the chorus of desperate cheers and wild laughter echoing across Manniqa Station.

Kat cheered with the rest, marvelling at how readily despair became hope. How swiftly the lie took hold.

The ground shook with the dhow’s impact in the unseen streets. The crowd’s cheers redoubled. Kat’s stuttered in her throat, the fires of the aetherios tattoo on her left forearm suddenly frigid as the souls of the dhow’s crew brushed past her – through her – and hissed skyward, clawing for the Deadwinds and demanding with silent, nebulous voices that she bear witness. She closed her thoughts to them and tried not to wonder at how many had joined the battle only because the Eternity Queen had given them no choice.

She leapt to the last rooftop, her expression composed to conceal her discomfort from the tall, lantern-jawed man standing at the far end, hands thrust into the pockets of scarlet and gold robes whose splendour were an ill match for his tousled, unruly dark brown hair. Stockier than Kat – whose athletic frame had more or less survived the banquets of governorship intact – but not yet quite run to fat, he filled the carriage roof as completely as any actor owned a stage. It was as if all the uncertainty and horror of that moment had come into being merely to serve as a backdrop to some great performance not yet arrived. So it always was with Tatterlain, who smiled often and revelled in attention but somehow seldom lost his dignity in the process… unless, of course, it served his ends.

“It happened again, didn’t it?” he said, without turning to look at her.

Kat grimaced. So much for concealing her discomfort. Then again, she supposed it shouldn’t be easy to keep secrets from friends. “You know it did.”

Thanks to the spider-work aetherios tattoo her father had inked on her left forearm, she’d talked to ifrîti – the fragments of souls that powered everything in Khalad from shrieker cannons to humble light-bestowing lumani – her whole adult life. Having those same ifrîti demand her attention was new, though it didn’t take genius to know why that had changed.

His smile turned wintry as he gazed out across the crowds. “I hate to say it, but you can’t save everyone.”

“Vallant would agree. I’m not Vallant.” Vallant, who’d vanished into the mists without a trace three months before. Which meant he was likely never coming back. The Veil devoured people, body and soul.

“You’re certainly prettier, in favourable light at least. That doesn’t mean I’m wrong.”

It didn’t, much as Kat wished otherwise. The railrunner was already well over capacity, the leading rooftops thickening with folk clutching tight to loved ones and thin belongings as harried custodians crammed ever more aboard. The score of custodians at the barricades wouldn’t stop a determined assault – especially if koilos were loosed to the slaughter. Every minute gambled the lives of those aboard against those who might yet reach salvation. But what else was there? Choosing who lived and who died took more than she had.

This is folly. You should leave.

The graveyard sigh washed silently across Kat’s thoughts. Conscious of Tatterlain’s eyes upon her, she fought to keep her disgust concealed. She’d had plenty of practice. So far as most of Khalad was concerned, Caradan Diar, the deposed Eternity King, was dead. And so he was. Sort of. Almost. Maybe.

“We can wait a little longer,” she said firmly.

Tatterlain twisted his lips, his left eyelid fluttering. Not for the first time, Kat wondered exactly what he’d seen in her expression. A master mimic didn’t become so without a knack for observation. “We can.”

The thin, stuttering wail of a distraught child pierced the cacophony.

There. Halfway along the platform to the thin barricade. A girl of maybe six or seven years with a threadbare stuffed paracat crushed to her chest. Her trailing ink-black hair flicked against the toy’s tufted ears as she twisted to and fro in the suffocating press of bodies, searching for a familiar face in among the unfeeling strangers. With her dark bronze complexion and willowy build, she could have been Kat’s younger self.

“Kiasta.” She murmured her father’s favourite curse. Her tolerance for crowds was little greater than her love for heights – her perch on the rooftops wasn’t entirely a contrivance of leadership – but she’d learned the hard way that selfishness gave the very worst of hangovers.

Steeling herself, she turned back to Tatterlain. “Watch the gate. If the redcloaks show—”

“Get the railrunner moving.” He nodded. “Actually, I don’t think you need go anywhere.”

The seething crowd parted before a duster-coated woman whose white hair flowed from beneath her broad-brimmed hat to brush the long straight sword buckled at her shoulder. She walked on, priestly and unhurried, seeming not to notice as desperate evacuees, otherwise on the brink of a shoving match, somehow found space to let her pass.

Rîma thumbed a tear from the child’s cheek, gathered her up and set out crosswise along the platform. Reunion between girl and distraught parents was as swift and inevitable as sunrise, mother crushing daughter to her chest as tightly as the child had her paracat. As a harried custodian ushered the three aboard an overcrowded carriage, Rîma raised her eyes to Kat’s and offered a steady, shallow nod.

“Always the show-off,” muttered Tatterlain, his tone absent of rancour.

Kat smiled. Even from her vantage atop the carriage, she’d not noticed the girl’s parents until the last moment, and yet Rîma had somehow marked them from within the thick of the crowd. “She has cause.”

You are out of time, breathed Caradan Diar.

She felt the heraldic’s arrival as a cold prickle across her tattoo a heartbeat before it coalesced into a thin indigo shimmer a pace to her front, hovering above the crowds.

The ifrît’s soulfire rippled into a passing semblance of a bodiless, featureless face, its lips barely moving as it breathed its message.

((Bad news, trallock.)) Its flat, emotionless tone jarred with the earthy colloquial Daric favoured by the captain of the Sadia’s Revenge. ((Redcloaks just swarmed the Kairon Street watchtower. It’s dirt to dinars that you’re next.))

Message delivered, the heraldic shimmered, its meagre soulfire already dispersing. Convention held that they were only good for a single message before the Deadwinds claimed them, but Kat and convention had parted ways a long, long time ago.

She reached out with her left hand, indigo flame racing along the spiderweb lines inked on her forearm as she fed the heraldic enough soulfire to sustain it for the return journey. She felt the ifrît’s pleasure and surprise mingle at the back of her thoughts – it was just aware enough to know how close it was to oblivion, and welcomed the chance to linger.

“Maxin? We’re getting under way, but we could use some cover.”

She wanted to add more, but the heraldic was already thinning, its indigo flames mingling with the backrush of steam from the distant locomotive. Gritting her teeth, Kat nodded to indicate that the message was done and withdrew her hand. “Thank you.”

The heraldic bled away, already speeding skyward. Kat glanced at Tatterlain.

“I’ll handle it,” he said, already walking backwards along the carriage towards the distant railrunner engine. “Just make sure you’re aboard.”

She ran along to the access ladder linking roof and stoop, waving down at the platform and pointing towards the barricaded gate. “Rîma!”

Rîma straightened, nodded and set off in parallel, the press of bodies parting as readily as before.

For a mercy, the crowds had cleared almost to nothing by the time Kat stepped off the stoop and onto the platform. Maybe sixty or seventy more to get aboard. They might actually have done it. They might actually have saved everyone.

Better than Vallant had ever managed.

Kat winced. Was there anything more pathetic than rivalry with the dead? And she’d no doubt that Vallant was dead, even if Tatterlain and some of the others clung to hope. The hungry mists of the Veil had claimed him, the Chainbreaker, its crew… and all of it her fault, as she’d put him up to the voyage.

Throat thick with guilt, she rounded on a man dragging a weighty traveller’s chest and falling further behind his fellow stragglers with every step. “Leave it!”

Stricken, he hesitated, but nodded. As the deafening blast of the railrunner’s whistle wailed beneath the station roof, he ran towards the nearest carriage.

As Kat approached the mound of clatter wagons, broken furniture and abandoned traveller’s chests that could generously be called a barricade, the nearest of the handful of custodians greeted her with a martial crispness that marked her as someone who’d begun her service under Tyzanta’s corrupt Bascari regime. But for all that, Overseer Ayla Sinair was an honest woman whose insights into the petty rivalries, feuds and inanities of Tyzanta’s daily life had smoothed the course of Kat’s brief governorship. You found your place in Khalad or one was found for you, or so the saying went. Sinair, like Kat, had fought to choose her own path. That common ground had soon overcome the unpleasantness of a first meeting that had seen Kat in a convict’s shackles. Long nights spent drinking away the frustrations of the day had cemented common ground into friendship.

“Lady Katija.” No amount of friendship had ever made Sinair abandon formality, just as no amount of repetition could dull Kat’s unease at being addressed as Lady Katija. Vallant had insisted that the title went with the governorship but, as far as Kat was concerned, titles were for the fireblood nobility, and she was as common a cinderblood as they came – even if her father had possessed ambition enough for a dozen noble houses. “I take it the situation’s changed?”

There’s no time for this, breathed Caradan Diar. You—

“Enough,” hissed Kat. Death had done nothing to quell the Eternity King’s persistence, nor his implacable pursuit of self-interest. If she died, so did he. It made for a reluctant alliance at best.

“Kairon Street’s fallen,” she told Sinair. “It’s time we were gone.”

Sinair grimaced. She’d never quite adapted to the fact that Tyzanta’s custodians no longer donned the androgynous silver vahla masks commonplace elsewhere, and wore her feelings more openly than an overseer should. “You heard the governor! Get ready to move.”

“Company’s coming!” shouted a custodian perched on the cab of one of the overturned clatter wagons halfway up the barricade.

Kat clambered up to join him. Beyond Manniqa Station’s gate, the lumani lights of the approach tunnel flickered, casting erratic shadows. Where the tunnel yielded to smoke-clogged skies, a dozen redcloaks advanced in loose formation, the stubby brass and polished wooden stocks of shriekers steady in their hands.

Sinair eased the barrel of her own shrieker over the makeshift rampart. “Vanguard patrol. They don’t know what they’re walking into. Not yet.”

The railrunner engine loosed another blast from its steam whistle. In the tunnel, the leading redcloak stiffened and barked an order. The vanguard broke into a run, eponymous scarlet cloaks streaming behind.

“Stay low,” said Kat. “Let them get close.”

All along the barricade, custodians levelled their weapons. Kat did likewise, more for show than purpose. Long range or short, she was a terrible shot.

She let the redcloaks approach to within twenty paces before giving the order to shoot. The heart-wrenching wail of shriekers echoed along the tunnel, swallowing dying screams as bolts of flame burned cloth and flesh to ash. Only a single return shot found its mark, hurling a custodian from the barricade’s summit, the fires fading and his soul fled before he hit the flagstones.

Kat grabbed at the barricade to steady herself as the souls of the dead and dying rushed through her, the voices louder, more unsettling for their proximity. And beneath them, something else. Something familiar, though she couldn’t quite place it. A soft, persistent pressure at the back of her thoughts. The feeling grew more diffuse as she tried to pin it down, her thoughts muddying… drifting… The past day and a half almost without sleep taking its toll.

Katija! snapped Caradan Diar, cold and clear.

Grateful despite herself for his intervention, Kat glanced back towards the railrunner. The platform was all but empty. They were the last.

“We’re done here.” She tried not to look at the dead custodian. “Sinair—”

She turned to find herself staring into the muzzle of Sinair’s shrieker.

“I can’t let you leave, Lady Katija.”

Custodians twisted around. Some raised their own shriekers to cover the overseer. Most were frozen, conflicted.

I tried to warn you. Self-satisfaction crowded Caradan Diar’s voice. A mentor indulging Schadenfreude for a student’s oversight. She’s here.

No need to guess who he meant. Not now. Not with Sinair’s expression contorting as if a piece of her was surprised by her own actions. That scrap of resistance faded before Kat had chance to speak, sealed behind Sinair’s eyes as unseen pressure warped her perceptions.

The Eternity Queen had a way of getting into people’s heads. Those rooted in structure and obedience were most vulnerable of all, their longing for a simpler time a fulcrum about which their personality shifted. It transformed rebels into loyal soldiers and loyal soldiers into hardened fanatics… and all without them truly being aware of what had been done to them. The one failing that made resistance even possible was that it only worked if the Eternity Queen was close.

She was in the city. Maybe closer even than that.

“Azra…” breathed Kat.

“Come quietly, lady,” said Sinair. “The Eternity Queen will forgive you.”

“I’m sure she will.” Kat held her gaze as the other custodians watched on, some with helplessness, some with outright horror. Each wondering who might be next to succumb. “But I won’t forgive myself… so you’re just going to have to shoot me.”

Eyes still on Sinair’s, she reached for her own shrieker.

Sinair’s brow creased. Her finger tightened on her trigger.

She grunted and fell forward, eyes glassy, as the pommel of Rîma’s sword cracked into the back of her skull, just behind the ear.

Kat lowered Sinair to the ground as gently as she could. So much for saving everyone. To die for the cause was one thing. Living to unwillingly betray it was something else. “You had to wait for the dramatic entrance, didn’t you?”

Rîma scabbarded her sword. “You’ll have to leave her.”

Kat grimaced. “I know.”

She steeled herself against heartache that begged her to indulge the familiar, hopeless dream that there was some way to bring Sinair to her senses. To rescue her friend from the madness that had claimed so many of those she loved. She’d wasted fruitless months on that dream. It had nearly killed her twice. But once the Eternity Queen had you, there was no coming back.

“Stars Below…” a custodian breathed further along the barricade.

The tunnel was no longer empty, but filled with a press of scarlet cloaks about a slender golden-gowned figure. Kat’s heart sank another notch. Even at a distance – even gilded in regal finery and bedecked with gemstones – there was no mistaking that woman, whose black hair and bronze complexion were so alike to her own that in another life strangers had mistaken them for sisters. Khalad knew her as the Eternity Queen. Tyzanta had hated her as Yennika Bascari. But to Kat, who’d loved her more than life itself, she’d always be Azra. The false goddess Nyssa’s first victim, and the vessel through which her ancient, malevolent spirit bent the mortal world to tyranny.

“Katija?” The Eternity Queen’s voice echoed along the tunnel. “I know that’s you down there. It’s over, but it needn’t be unpleasant.”

Bad enough that she still looked like Azra. Worse that she sounded like her too, even at a distance. The languid self-assurance that bewitched or revulsed according to her mood.

But she wasn’t her, not really. Azra was gone.

“Go!” snapped Kat.

The custodians raced back along the platform. Rîma, predictably, did not. Instead, she joined Kat at the barricade and regarded the scores of marching custodians with her customary calm.

“I confess, I worry about what you intend,” she murmured.

As do I, breathed the Eternity King, rather more acidly. Azra is not yours to save.

“I know,” Kat replied, the act of choosing her words to satisfy two parties – one of whom couldn’t hear the other – having become second nature. The redcloaks didn’t matter any longer. Even at a flat run they’d not reach the railrunner in time. But every step the Eternity Queen took increased the possibility of her seductive presence touching on the crowded carriages. And if that happened…

Barely bothering to aim – at that distance, it hardly mattered – Kat brought up her shrieker and fired a volley. Shots screamed along the tunnel, the echoes deafening in their backwash. Fire flared briefly against walls, roof and flagstones, filling the tunnel with dust and rubble. A single redcloak pitched forward, his cloak ablaze.

The column shuddered to a halt, its rear ranks retreating as they ushered the resisting Eternity Queen back towards the smoke-wreathed sky and out of range. Kat indulged a sharp smile. Thralls or willing servants, the redcloaks were the Royal Guard, with a bodyguard’s duties and instincts – especially with the bodies of their vanguard littering the barricade approach.

The railrunner’s whistle wailed three short blasts. Metal shrieked as gears bit and wheels shuddered to motion. With the yawning rumble of a slumbering giant rousing to wakefulness, the railrunner pulled away, the folk on its rooftops silhouetted against the roiling steam.

“Time to leave,” said Kat.

With a last, unspoken apology to the unconscious Sinair, she turned her back to the tunnel and ran headlong for the departing railrunner.

Rîma overtook her without obvious effort. She leapt gracefully onto the stoop of the rearmost carriage and swung herself over its guardrail in a swirl of coat tails.

Pushing trembling legs to one last effort, Kat launched herself at the stoop moments before the railrunner left the platform behind. Rîma grabbed her by the wrists and hauled her unceremoniously aboard.

By the time Kat righted herself, they were beneath open skies. The slums of Undertown rushed past, the railrunner’s acceleration banishing the glass and steel arch of Manniqa Station’s roof to the middle distance. She barely noticed the sleek, scorched hull of the Sadia’s Revenge swoop in from the south, pockmarked sails furling as she matched the overburdened railrunner’s speed. Kat had eyes only for the burning city, and the black-sailed warships circling its ramshackle smoke-wreathed spire.

Tyzanta, last and greatest of the free cities, and everyone in it, now belonged to the Eternity Queen.

“This wasn’t your fault,” murmured Rîma.

Kat gripped the guardrail until her knuckles ached. “I know.”

But as the city outskirts yielded to the arid red plains and black pine forests of the Zaruan lowlands, all she could think was that Vallant would have handled things better.

“Nearly done. Just hold that grip-heel steady. I don’t want my nose burned off.”

Mirzai glanced down through the ladder’s bowing, sun-bleached rungs. Tarin stood fifteen feet below, his grip-heel spanner wedged between the spokes of the governor valve’s flywheel. For all that Mirzai loved his nephew like a son, the boy was reaching that difficult age where boredom and longing transmuted vital instructions into easily dismissed suggestions.

“Stop fussing,” the fifteen-year-old called back. He’d inherited his waspishness from his mother, alongside the thick black hair cut short to hide its curl, and angular features that would have been the envy of any fireblood. “I know what I’m doing.”

Mirzai stifled a smile. There were times when it felt as though Midria was still with them, speaking through her son. She’d never suffered fools gladly, and seldom laid eyes on a bigger fool than her younger brother. She’d have been unbearable but for the generosity her sharp tongue concealed. The reminder that Tarin was very much his mother’s son was always welcome. They were the only family either had left.

But whether Tarin or Midria’s departed spirit appreciated it or not, it was better not to take chances. The corroded pipe was a part of a feedline covered by a dilapidated planked roof and suspended above the ruddy plains in a tangled wood-and-steel trestle. It drew unprocessed vapours from the valley bore-rigs to feed the hungry refinery on the edge of town. Making a mistake on the other side of the refinery was costly – every breath of the precious eliathros gas that wisped into the winds was one that couldn’t fill a skyship’s buoyancy tanks – but all manner of mingled vapours churned within the feedline, blackfire damp among them. If Tarin’s grip slipped – if the greased cork lining the sealant valve had begun to decay – then one spark would do more than burn off Mirzai’s nose.

There was a reason the refinery was half a mile outside town.

Mirzai peered at the damaged section, which belonged to one of five pipes borne by the trestle. It was already a patch job in a superannuated system: one of three segments – each roughly the length and girth of Mirzai’s stocky forearm, their ochre paint long since scratched and scored by the ruddy grit blown off the hills – that had replaced a much longer section at some point in the past. Just as well, because replacing a fully sized pipe would have needed six pairs of hands and a block-and-tackle to hoist the new section into place. The point of failure itself was a hairline crack along the pipe’s upper slope. Just enough for the gases to seep away. Harmless enough to start with, will barely a whiff of dropped pressure showing on the dials to rouse worries. But so many things were harmless enough to start with.

With a last check that the ladder was secure, Mirzai reached through the tangle of pipes and support struts and groped blindly to connect his own grip-heel with the bolts securing the damaged pipe to its neighbour.

Neglected and battered by the elements – on the rare occasions the rainstorms of the Mistrali swept across Araq’s hills, they did so with all the fury of an uninvited guest – the bolt refused to budge.

“Skrelling thing,” muttered Mirzai. Even in late afternoon, the heat was punishing. He wiped calloused fingers across his sweaty brow and smoothed back his thick black hair to keep it from falling into his eyes. His hand was already filthy from hitching the replacement pipe in its rope slings above the damaged section.

Sliding his feet to the edges of the ladder’s rungs, he looped his left forearm up and over the trestle’s nearest strut and braced his right palm on the spanner’s leather-wrapped heel, the better to put his weight into the next attempt. With a screeching, crackling sigh, the bolt gave to the tune of a quarter-turn. Flakes of rust trickled to the sun-bleached grass a dozen feet below, setting a startled mouse to flight.

The next bolt required the same persuasion, but the four that followed had clearly learned from their peers and surrendered without a fight. Ever alert for the telltale hiss and bitter odour of escaping blackfire damp, Mirzai loosened each in turn then shifted his attention to the pipe’s far end. When these too were defeated, he worked the pipe through the gaps between its neighbours. It vanished into the grass with a rustle and a muffled thump.

Mirzai’s nostrils rankled at the scent of blackfire damp. His heart skipped, but it was a wisp only, soon smothered by the bitter juniper borne down from the hills.

“You all right up there?” called Tarin.

“Just you worry about that valve.” Mirzai winced, knowing he’d spoken too harshly. “Blackfire damp trapped in the seal, that’s all. It happens.”

“Any idea what caused it? Soiled alloy, maybe?”

Mirzai smiled at the hint of excitement. Soiled alloy meant that some greater force – greed maybe, or incompetence – lay behind the damage. Something Araq’s custodians could pursue and punish. Much more interesting than the dull truth that maintenance was a long, tedious and necessary labour that never ended.

“Not this time. The metal’s expanded and cooled once too often. Every inch of this line’s seen better days.”

“Like you?”

Mirzai ignored the jibe. Though he was barely into his mid thirties, that still left a ravine twenty years wide between them. Sometimes it simply wasn’t for crossing. “I’ll talk to Saheen about getting a crew up here to repaint it and fix the roof.” Of the dozen or so planks that should have shaded his section of the feedline, most were sagging and three were missing entirely. Not a lot of use for fending off sun or rain.

Tarin snorted. “Like she’ll pay for that. Cheaper to keep sending us to bake up here.”

“Like I said, I’ll talk to her.”

Araq’s overseer was famously tight-fisted – and necessarily so, given how few dinars there were to go around. But she was also a good woman and smart enough to know that no amount of patchwork would keep the feedline

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...