- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

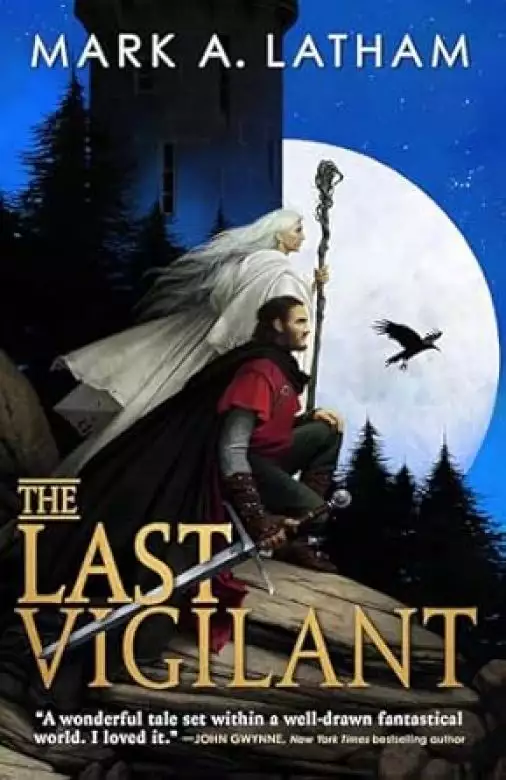

Synopsis

Set in a world where magic is forgotten, monsters lurk in the dark woods, and honorable soldiers are few, this utterly gripping epic fantasy tells the story of two flawed humans, an out-of-practice wizard and a hot-headed sargent, who are thrust into the heart of a mystery that threatens to unravel their kingdom's fragile peace.

Shunned by the soldiers he commands, haunted by past tragedies, Sargent Holt Hawley is a broken man. But the child of a powerful ally has gone missing, and war between once peaceful nations is on the horizon. So, he and his squad have been sent to find a myth: a Vigilant. They are a rumored last survivor of an ancient and powerful order capable of performing acts of magic and finding the lost. But the Vigilants disappeared decades ago. No one truly expects Hawley to succeed.

When he is forced to abandon his men, he stumbles upon a woman who claims to be the Last Vigilant. Enelda Drake is wizened and out of practice, and she seems a far cry from the heroes of legend. But they will need her powers, and each other, to survive. For nothing in the town of Scarfell is as it seems. Corrupt soldiers and calculating politicians thwart their efforts at every turn.

And there are dark whispers on the wind threatening the arrival of an ancient and powerful enemy. The Last Vigilant is not the only myth returning from the dead.

Release date: June 24, 2025

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 592

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Last Vigilant

Mark A. Latham

187th Year of Redemption

Holt Hawley hunched over the reins, the wagon jolting slowly down the track. Sleet stung his face, settling oily and cold on his dark lashes and patchy beard.

The whistling wind had at least drowned out the grumbling of his men, who sat shivering in the back of the wagon. Their glares still burrowed into the back of his head.

It mattered not that Hawley was their sargent. The men blamed him for all their ills, and by the gods they’d had more than their fair share on this expedition. Twice the wagon had mired in thick mud. On the mountain road, three days’ rations had spoiled inexplicably. Now their best horse had thrown a shoe, and limped behind the wagon, slowing their progress to a crawl. They couldn’t afford to leave the beast behind, but risked laming it by pressing on. Whatever solution Sargent Hawley came up with was met with complaint. He was damned if he did and damned if he didn’t.

Tarbert rode back up the track, cutting a scarecrow silhouette against the deluge. He reined in close to the driver’s board, face glum, still mooning over the hobbling horse that was his favourite of the team.

“V-village ahead, Sarge,” Tarbert said, buckteeth chattering. “Godsrest, I th-think.”

“You see the blacksmith?” Hawley asked.

“Didn’t s-see nobody, Sarge.”

“Did you ask for him?”

“Not a soul about.”

“What about a tavern?” That was Nedley. It was only just dawn and already he was thinking of drink.

“No tavern, neither.”

“Shit on it!” Nedley grumbled.

“That’s enough,” Hawley warned. He pulled the reins to slow the horses as the wagon began to descend a steeper slope.

“Typical,” Beacher complained.

Hawley turned on the three men in the back. Beacher was glaring right at Hawley, face red from the cold, beady eyes full of reproach.

“What is?” Hawley said.

“Three days with neither hide nor hair of a living soul, then we find a deserted village. Typical of our luck, isn’t it, Sargent?”

Ianto sniggered. He was an odd fish, the new recruit. A stringy man, barely out of youth, yet his gristly arms were covered in faded tattoos, symbols of his faith. His hair showed signs of once being tonsured like that of a monk, the top and rear of his scalp stubbled, fringe snipped straight just above the brow. He’d proved able enough on the training ground, but would speak little of his past, save that he’d once served as a militiaman in Maserfelth, poorest of the seven mearcas of Aelderland. He’d bear watching; as would they all.

Hawley turned back to the road, lest he say something he would regret.

“Awearg,” someone muttered.

Hawley felt his colour rise at the familiar slight. Again he held his tongue.

The men mistrusted Hawley. Hated him, even. Bad enough he was not one of “the Blood” like most of them, but even Ianto was treated better than Hawley, and he was a raw recruit. For Hawley, the resentment went deeper than blood lineage. For his great “transgression” a year ago, most men of the Third agreed it would’ve been better if Hawley had died that day. They rarely passed up an opportunity to remind him of it.

These four ne’er-do-wells would call themselves soldiers should any common man be present, but to Hawley they were the scrapings from the swill bucket. Hawley’s days of fighting in the elite battalions were over. Now his assignments were the most trivial, menial, and demeaning, like most men not of the Blood. Beacher, Nedley, and Tarbert served under Hawley in the reserves only temporarily—it was akin to punishment duty for their many failings as soldiers, but their family names ensured they’d be restored to the roll of honour once they’d paid their dues. For those three, this was the worst they could expect. For Hawley and Ianto, it was the best they could hope for. Command of these dregs was another in a long list of insults heaped on Hawley of late. But command them he would, if for no other reason than a promise made to an old man.

The words of old Commander Morgard sprang into Hawley’s mind, as though they’d blown down from the distant mountains.

What you must do, Hawley, is set an example; show those men how to behave. Show them what duty truly means. But most of all, show them what compassion means. When I’m gone, I need you to lead. Not as an officer, but as a man of principle. Can you do that?

Hawley had not thought of Morgard for some time. He reminded himself that the old man had rarely said a word in anger to the soldiers under his command. He had trusted Hawley to continue that tradition when he’d passed.

He’d expected too much.

From the corner of his eye, Hawley saw Tarbert cast an idiotic grin towards Beacher. Then Tarbert spurred his horse and trotted off down the slope.

The dull glow of lamps pierced the grey deluge ahead. Not deserted, then.

They’d travelled two weeks on their fool’s errand, as Beacher liked to call it. And at last they’d found the village they searched for.

Godsrest.

“Godsrest” sounded like a name to conjure with, but in reality was a cheerless hamlet of eight humble dwellings, a few tumbledown huts, and one large barn that lay down a sloping path towards a grey river. The houses balanced unsteadily on their cobbled tofts, ill protected by poorly repaired thatch.

Two women summoned their children to them and hurried indoors. That much was normal at least. As Hawley knew from bitter experience on both sides of the shield, soldiers brought trouble to rural communities more often than not. There was no one else to be seen, but though the sun had barely found its way to the village square, it was still morning, and most of the men would be out in the fields. There was no planting to be done at this time of year, especially not in this weather. But it was good country for sheep and goats, for those hardy enough to traipse the hilly trails after the flock. In many ways, Hawley thought soldiering offered an easier life than toiling in the fields. A serf’s lot was not a comfortable one, not out here. Here, they would work, or they would starve.

Hawley cracked the thin layer of ice from a water trough so the horses might drink. Tarbert unhitched the hobbling gelding from the back of the wagon and led it to the trough first.

Beacher spat over the side of the wagon. “I can smell a brewhouse.” He looked to Nedley, hopefully, who only snored.

The yeasty scent of fermenting grain carried on the wind. A late batch of ale, using the last of the barley, Hawley guessed. It’d be sure to pique Nedley’s interest if the man woke up long enough to smell it.

“We’re not here to drink,” Hawley said.

“Why are we here? There’s nothing worth piss in this wretched land. You know as well as I there’s no Vigilant in those woods. Not the kind we need.”

“If they’ve got his ring, stands to reason he exists.”

“Pah! Dead and gone, long before any of us were born. More likely the merchant found an old ring and was planning to sell it, but when he lost his consignment, he invented this fairy story to save his neck. Face it, he had no business being this far north. The only people who use the old roads are outlaws and smugglers. Mark my words, we’re chasing shadows. There’s no True Vigilant anywhere.”

Hawley had been ready for this since they’d left the fort, but it made him no less angry.

“So what if there isn’t?” Hawley snarled. “You reckon that frees you from your duty?”

“My duty is to protect the good people of Aelderland, not travel half the country looking for faeries.”

Ianto leaned against the wagon, watching the argument grow. Nedley stirred at last, peering at them from the back of the wagon through half-closed eyes.

Maybe Beacher had a point, but this wasn’t the time to admit it. Hawley took a confident stride forward, summoning his blackest look. Beacher shuffled away from his advance.

“If there’s a True Vigilant, he’ll be able to find them bairns. It’s them you should be thinking about.”

“There’s only one child Lord Scarsdale cares about—that Sylven whelp—and only then because his bitch mother wants to start a war over him. That’s what you get, putting a woman in charge of an army.”

Hawley waved the protest away tiredly. He’d heard it all before.

“Besides,” Beacher went on, growing into his tirade, “even you can’t believe they still live.”

Even you. Beacher’s lack of respect was astounding. He’d barely known Hawley at the time of the sargent’s great transgression. His animosity was secondhand, but seething nonetheless. Men like Beacher needed something to hate, and in times of peace, that something might as well be one of their own. Sargent Holt Hawley, the Butcher of Herigsburg, bringer of misfortune: “awearg.”

“Then we’ll find the bodies, and take ’em home,” Hawley snapped. “If you can’t follow orders, Beacher, you’re no use to me. Leave if you like. Explain to Commander Hobb why you abandoned your mission.”

Beacher looked like he might explode. His face turned a shade of crimson to match his uniform. His hand tensed, hovering over the pommel of his regulation shortsword.

Do it, you bastard, Hawley thought. The sargent had taken plenty of abuse this last year, maybe too much. Some of the men mistook his tolerance for cowardice instead of what it really was: penance. It made them think he would shy from a fight. It made them overreach themselves.

“They say a True Vigilant can commune with the gods.” The voice was Ianto’s, and it was so unexpected, the tone so bright, that it robbed the moment of tension.

Hawley and Beacher both turned to look at the recruit, who still leaned nonchalantly against the wagon, arms folded across his chest.

“Commune with the dead, too. And read minds, they say. That’s how they know if you’re guilty of a crime as soon as they look at you. Such a man is a rarity in these times. Such a man would be… valuable.”

“Speak plain,” Beacher spat.

Ianto pushed himself from the wagon. His fingers rubbed at a little carved bone reliquary that hung about his neck, some trapping of his former calling. “Just that the archduke sent us, as the sargent said. The Archduke Leoric, Lord Scarsdale, High Lord of Wulfshael. Man with that many titles has plenty of money. Plenty of trouble, too—we all know it. The Sylvens could cross the river any time now, right into the Marches. Might even attack the First, then it’s war for sure.”

“The First can handle a bunch of Sylvens,” Beacher said.

“Maybe.” Ianto smiled. “But maybe there’s a handsome reward waiting for the men who find the True Vigilant and avert such a war. I don’t know about you, brother, but I think it would be not unpleasant to have a noble lord in my debt.”

“And what say you, Sargent?”

Hawley almost did not want to persuade Beacher to his cause at all. Part of him thought it would be better to throw the rotten apple from the barrel now, and be done with it. There was a saying among the soldiers “of the Blood”—something about cutting a diseased limb from a tree. But for all his faults, Beacher was liked by the others. Hawley was not. That would make harsh discipline difficult to enforce.

“I say if by some miracle we turn up a true, honest-to-gods Vigilant after all this time,” Hawley said at last, “they’ll be singing our names in every tavern from here to bloody Helmspire. But if you don’t follow your orders, we’ll never know, will we?” Hawley added the last part with menace.

“And if… when… we don’t find the Vigilant?” Beacher narrowed his eyes.

“Then we return to the fort, and be thankful we’ve missed a week of Hobb’s drills.” Hawley held Beacher’s contemptuous glare again.

In the silence, there came the ringing of steel on steel, drifting up the hill from the barn.

Hawley and Beacher looked at Tarbert as one.

“No blacksmith?” Hawley said.

Tarbert laughed nervously.

“There you go,” Ianto said. He came to Beacher’s side and patted the big man on the shoulder. “Our luck’s changing already.”

Beacher finally allowed himself to be led away, still grumbling.

The sargent stretched out his knotted back, feeling muscles pop and joints crack as he straightened fully. Only Tarbert matched Hawley for height, but he was an arid strip of land who barely filled his uniform, with a jaw so slack he was like to catch flies in his mouth while riding vanguard. By contrast, Hawley was six feet of sinewy muscle, forged by hard labour and tempered in battle. He shook rain from his dark hair, and only then did he remember he was not alone.

Nedley was still on the wagon, watching. For once, he didn’t look drunk. Indeed, there was something unnerving in the look he gave Hawley.

Hawley shouldered his knapsack, and hefted up Godspeaker—a large, impractical Felder bastard sword. Non-regulation: an affectation, a prize—a symbol of authority. The men hated that about him, but Hawley could barely care to add it to the tally.

“Make yourself useful, Nedley,” Hawley said, strapping the sword to his back. “Find some supplies. And bloody pay for them. Show the locals that we mean well.”

Hawley snatched the reins from Tarbert, who still looked forlorn. He cared more for the gelding than for most people. Baelsine, named for the blaze of silver grey that zigzagged up its black muzzle. He talked to it like a brother soldier.

“Help Nedley. I’ll go see the smith.”

A small forge blazed orange. A stocky, soot-faced man with a great beard and thick arms tapped away at a glowing axe-head.

“A moment, stranger,” the man said, without looking up from his work.

Hawley basked in the welcome warmth of the bloomery, indifferent to the acidic tang of molten iron on the thick air.

The smith gave the axe-head a few more raps, before plunging it into a water trough, creating a plume of steam with a satisfying hiss. Only then did he look up at his visitor. Only then did he see the crimson uniform. “My apologies. I… I didn’t know.”

Hawley waved away the apology. “We need your services.”

The smith squinted past Hawley. “How many soldiers?” he asked, suspicion edging into his voice.

“Five.”

“Expectin’ trouble?”

“No more than the ordinary.” It had become standard wisdom that five men of the High Companies were worth more than twenty militia, and no outlaw of the forests would dare confront them. Fewer than five, and there’d be insufficient men to perform sentry and scouting duties. More importantly, there would not be enough to adopt the fighting formation favoured by the companies. The wall of steel. In full armour, every High Companies soldier clad their left arm in pauldron, gardbrace, and vambrace of strong Felder steel, adorned with an ingenious system of five interlocking crescent-shaped plates. When the arm was locked, a spring-loaded mechanism within the soldier’s gauntlet would push the plates outwards, forming a rough circle of steel petals, almost like a shield; but when the arm was straightened, the plates retracted, leaving the arm free of any burden. Some men of the High Companies even had the skill and speed to trap an enemy’s blade within the plates, snapping it in twain with a deft movement. In the press of battle, the soldiers would stand with their armoured left arm facing the foe, right hand wielding the short, thrusting blade, attacking in pairs with one man free to protect the rear and pick off the stragglers. That man was usually Hawley, whose heavy Felder sword needed room to do its grim work.

“This horse threw a shoe a few miles back.” Hawley pointed to Baelsine, tethered near the barn.

The smith squeezed past his anvil to the horse. He lifted the hoof, and sucked at his teeth.

“Won’t be fit for ridin’ today. I’ll shoe him. He can go in the paddock with my dray.”

“Our own drays need feed and water.”

“Ye planning on staying long?”

“Not if we can help it.” Hawley didn’t need consent to bunk in the village, but didn’t like to flaunt his authority. “Perhaps we can be on our way today… with your help.”

“I’m no miracle-worker, sir. That horse’ll go lame if—”

“We can travel on foot from here. But I need you to point the way.”

The smith’s expression grew guarded. Hawley wondered if the man had cause to be suspicious of soldiers, or whether it was the custom of such isolated folk to be wary of strangers.

“Don’t know what help I can be,” the man said, wiping his hands on a rag. “Nor anyone else here, neither. We’re simple folk. We keep to our own.”

“Three weeks ago, perhaps more, an ore merchant passed through Godsrest. He’d been set upon. Beaten, nearly killed. You remember?”

“Aye, I remember.”

“Men from this village helped him fetch his belongings. And among those belongings was a silver ring. You remember that?”

“Something of the like.”

“Someone saved that merchant’s life. We think it was the same man who owned the ring. We need to find him.”

“Don’t know nothing about that. Some o’ the lads brung him to the village. I mended his wagon, he stayed a couple o’ days while he recovered his strength, then he left.”

“Fair enough.” Hawley took out his map and unfolded it. “You can show me where he was found?”

The smith squinted at the map. “Old map,” he said. “Them roads aren’t there any more. Forest claimed ’em, and nobody in their right mind would travel ’em. Exceptin’ your merchant, o’course.”

“Show me, as best as you can.”

The smith pointed at a spot in the woods, near to a road that supposedly was no longer there.

Hawley circled the spot with his charcoal, and frowned.

“How did you know?” he asked.

“How’d you mean, sir?” Was that nervousness? A quaver of the voice; a twist of the lip?

“You said you brought him here. But how’d you know to look for him?” Hawley studied the map. “No shepherd of any sense would graze his flock north of the river, let alone enter that forest. Unless he’s particularly fond of wolves—or bandits.”

“Had a bad season. Some o’ the younger lads were out hunting the game trails. Heard the commotion. When they got there, they found an injured man and an empty wagon.”

“Poaching in your lord’s woods?” Hawley said.

“Nobody lays claim to the Elderwood, sir. Not our lord, not nobody else. Them woods is cursed, they say. Them woods is… haunted.”

“But your hunters aren’t afraid of ghosts?”

“They’ve the good sense not to stray too far.” The smith eyed Hawley carefully. “You’re not a soldier born,” he said at last.

Hawley glowered.

“I mean no disrespect. All us folk of Godsrest abide by the king’s law, and serve the king’s men when required. It’s just that… well… you try to speak proper, sir, is what I mean. But your roots are clear. It’s like working a bloom that don’t contain enough iron, if you take my meaning.”

“I’m a sargent of the Third Company, that’s all that matters.”

Footsteps squelched loudly along the muddy path. Ianto appeared, that thin smirk upon his lips. He looked at the smith with keen eyes—mean eyes, Hawley thought.

“I told you to stay with the wagon,” Hawley said sharply.

“I thought you’d want to know there’s some… trouble.”

There was something almost lascivious about Ianto’s manner, and it sent a cold, warning creep up Hawley’s spine.

“What kind of trouble?”

“The kind that gives soldiers a bad name.”

Hawley followed the sounds of shrieking, pleading. The odd obscenity. The pained bleating of some animal. Hawley rounded the cob wall of a cottage to see three women of middle age remonstrating with Nedley. The soldier was stood near the largest hut, foot resting on a keg, sloshing ale down his throat from a flagon. Two more kegs lay on the track nearby. One had cracked open, dark ale foaming into the dirt. Behind Nedley, Beacher played tug-of-war with a red-headed boy, over the rope around the neck of a nanny-goat swollen with kid. The beast bleated pitifully as the noose tightened about its neck. Tarbert stood near, clapping his hands in joy at the unfolding chaos.

The woman doing most of the shouting rushed to Nedley, shrugging aside the half-hearted attempts of the others to hold her back. She pounded her fists against Nedley’s chest. The soldier belched in her face, and shoved her away roughly. She spun into the arms of her companions as Nedley drained his flagon.

“Nedley!”

At Hawley’s shout, Nedley narrowed his eyes in an insolent glare, the likes of which Hawley had never seen from the man. He wiped ale foam from his beard, but he did not answer.

As Hawley drew near, Nedley’s hand moved just an inch towards the pommel of his sword.

That was everything Hawley needed to know. He lowered his head like an angered bull, and didn’t so much as check his stride. Nedley thought better of drawing steel. Hawley shoved Nedley away from the hut. The drunkard shot Hawley another glare, but did nothing.

The boy cried out. The three women wailed and cursed.

The boy was in the mud now, holding his face, sobbing. Beacher had slapped him to the ground. But the boy cried not from pain but from sorrow. The goat was dead, blood spilling onto dirty straw from an ugly wound in its throat. Beacher had his sword in his hand, a grin on his blood-flecked face. Tarbert laughed like an imbecile. His laughter died on his lips when he saw Hawley.

Hawley kicked open the gate of the animal pen.

Beacher hadn’t even noticed Hawley. At the interruption he said only, “Nedley, I told you—”

Hawley grabbed Beacher by the ear, twisted hard, and pulled him away from the goat with all his strength. Beacher squealed like a stuck pig as Hawley dragged him to the gate. Hawley spun the man around, and gave him a kick up the arse that sent him face-first into the dirt, his shortsword skittering from his hand.

Tarbert had taken a step forward, slack-jawed face more agawp than usual. Hawley slapped him hard across the side of the head for his trouble. Tarbert cowered like a kicked dog.

Hawley took one look back at the weeping boy and the dead goat. The animal was worth far more alive than dead to these people. The family’s meagre fortunes may well have depended upon the creature. And now they would struggle, for the simple greed of a soldier. Hawley stepped onto the track, Beacher in his sights.

Nedley had picked up his flagon again, more concerned with saving the last undamaged ale keg than helping his brother soldier. The villagers could scarce spare the ale either, Hawley thought. But one thing at a time.

One of the women pushed past Hawley to see to the boy. The other two, realising Nedley was no longer standing in their way, came to scream at Beacher.

Ianto reappeared. He stood over by the cottage, leaning against the wall, watching. Grinning.

Now the smith appeared, hammer in hand. That was the danger. Hawley had to deal with Beacher before any villager got involved. Otherwise, he’d be hard-pressed to stop even this band of good-for-nothings taking vengeance on the peasants.

Beacher rolled over, scrambling away on his elbows. “Don’t you touch me!” he snarled, blinking away mud from his eyes. His hand found the pommel of his shortsword in the dirt. His fingers curled around the hilt, and his expression changed at once. He clambered to his feet and spat, “You filthy mongrel!”

Mongrel. Not one of “the Blood,” who could trace their family back through five or more generations of military service. Looking at the state of the men around him, Hawley couldn’t take it as much of an insult.

Hawley advanced another step. “Sheathe that sword,” he said quietly, almost in a growl. “Sheathe it, or I’ll kill you.” He held Beacher’s gaze, saw the man’s eyes falter. Beacher believed him. He was right to.

Beacher pleaded with his brother soldiers left and right for support. Hawley heard Tarbert behind him, but the dullard was of little concern. Nedley… now there was an unknown quantity. Up until now, Hawley hadn’t taken the drunkard seriously. That could have been a mistake. Nedley was staring at Hawley with utter detachment, like a butcher appraising which cut of meat to take next. But he didn’t make a move. When Beacher looked to Ianto, the recruit gave only the merest shrug of his shoulders, as if to say, “This is not my fight.” He may not have been a friend to Hawley, but nor was he one of the Blood. He’d wait and see which way the wind blew before committing himself.

Beacher stood alone, and he knew it. He took a moment to weigh up his chances against Hawley, and found them lacking. He sheathed the blade and spread his palms.

Hawley marched to Beacher, loomed over him, pressed his forehead into the bridge of the man’s nose. Beacher averted his eyes, like a wild dog that had just lost a pack challenge. Hawley reached to Beacher’s belt and took the man’s sword away with no resistance.

Other villagers arrived now. Seven or eight men and youths tramped up the hill, pointing, chattering. Their approach was cautious. There weren’t enough men in this village to cause the soldiers real problems, but enough that they might try. And die.

Any sense of decorum was lost. Any chance Hawley’s reserves had of looking like proper soldiers was gone.

“Ianto, Nedley. Get him away,” Hawley said. “To the bridge. Wait for me there.”

Neither man moved. Nedley gazed at the flagon, weighing up the order.

“I said get him away. Now.”

Ianto exchanged looks with Nedley and shrugged again. Nedley finished his dregs, tossed the flagon aside, and weighed in. Together they led Beacher away from the gathering villagers, down towards the river.

Tarbert staggered from the pen at last, nursing his sore ear. Hawley jerked his head in the direction of the others. Without a word, Tarbert followed.

Rightly or wrongly, Hawley had done the men an insult—one that might yet come back to bite him on the arse. As king’s men, they had the right to claim whatever they wanted from a serf, and by denying them their perceived due, Hawley had only deepened their loathing of him. He might even face more punishment back at the barracks, once Beacher had made his inevitable complaint. Hawley was past caring. What he needed to do right now was make amends with the villagers.

“Master Smith—” Hawley ventured.

“Godsrest is a peaceful place,” the smith interrupted. “Apt named, for we honour the gods here and invite no trouble. You’ve brought trouble to our door.”

The other men drew nearer. Hawley weighed up his chances of regaining the smith’s trust before they took exception to his presence.

“They’re soldiers… not good ones, I admit. But you’ll have no more trouble.”

“No?”

“No. Look, Master Smith—”

“Gereth. My name is Gereth. And that boy over there is my son.”

Hawley turned to see the dishevelled lad on his feet at last, being comforted by a woman. From the mane of red hair that tumbled from her bonnet, Hawley guessed she was his mother—Gereth’s wife. She held her son close, and glared accusingly at Hawley, who cursed Beacher’s name under his breath.

“Gereth, then. You know the law. You know the power of the High Companies. I would choose not to exercise that power. Let’s come to an arrangement instead. See to our horses as agreed, and I’ll pay you fairly.”

“That much I’ll do, sir, as duty to manor and king dictates.”

“You don’t have to call me ‘sir.’ My name’s Hawley. Holt Hawley. You were right before, I am a common man, from a place much like this. I chose this life ’cause I was tired of seeing common folk—people like us—downtrodden and uncared for.”

“Then you chose poorly, Holt Hawley.”

“Maybe. But there’s no leaving the companies once your bunk is made, unless it be on a pyre, an enemy’s blade, or the end of a noose. So I do what I can, and I’ll at least talk straight with you.”

The others gathered around. Hawley didn’t know how much they’d overheard, and it didn’t matter. As a craftsman, Gereth was of a higher station than they. Gereth was the one he needed to convince.

“You had little reason to trust me before,” Hawley went on, “and even less now. But I’ll tell you why we’re here. This past year, six bairns have been taken from their homes. Six—that we know of. One of them is a lad of wealth, a foreigner. You’ve no reason to care for such a boy, why would you? But the others… they’re from villages like this, poorer than this. Boys and girls of Aelderland. Boys younger than your own. They’re lost, and nobody can find them. Not the high lords, not the companies, and certainly not the bloody Vigilants. But it’s said that there’s somebody in these parts who could help. A True Vigilant, of the old order. If it’s true, then maybe he can find those children, where others have failed.”

Gereth shook his head. “Fairy stories, Holt Hawley. There’s nobody alive who’s ever seen such a man. Not many who’ve even heard of one, neither.”

“That merchant,” Hawley persisted, “said he was helped by a mysterious stranger. Didn’t get a good look at him, but he did find his ring. A Vigilant’s ring.”

Gereth waved a dismissive hand. “As I’ve said, there’s nowt in them woods but trouble. If you want to go chasing shadows, that’s your affair. All we can offer you is food and water for yer horses and a dry place for yer wagon.”

Hawley sighed

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...