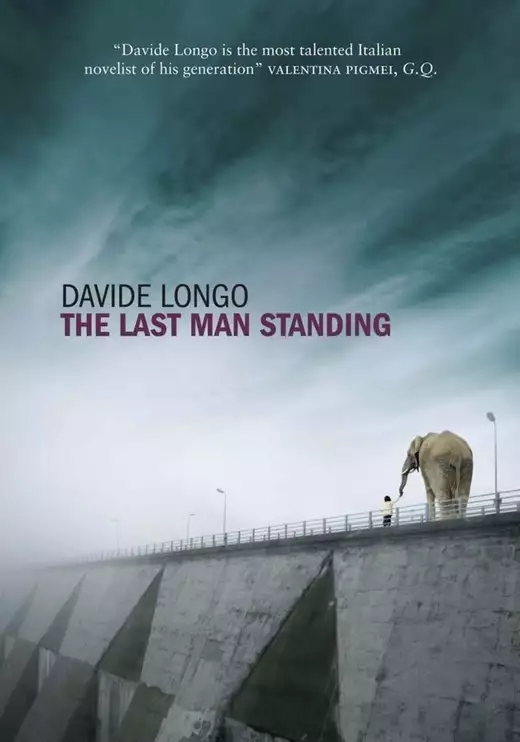

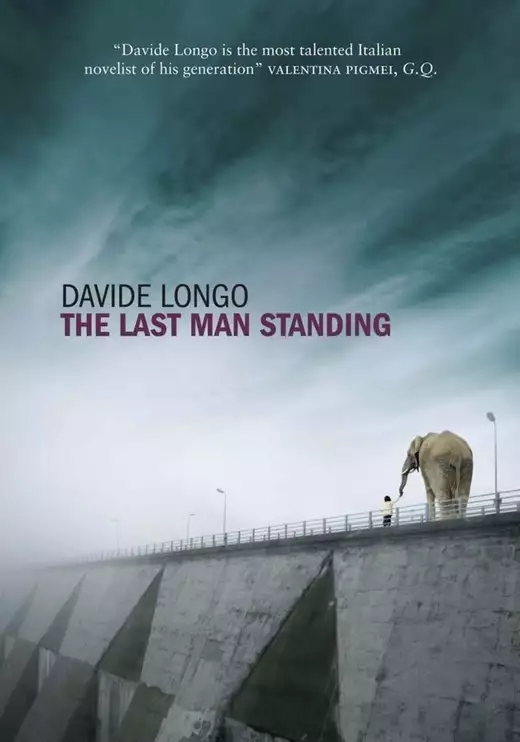

The Last Man Standing

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A chillingly plausible novel about the collapse of Italian society and one man's struggle to retain his humanity amid the horror "A bleak, lyrical tale that evokes Cormac McCarthy's The Road.... Gruesome, intense, and strange... a eurozone nightmare brought to life on the page."-- James Lovegrove, Financial Times It is 2025, and Italy is on the brink of collapse. Borders are closed, banks withhold money, the postal service stalls. Armed gangs of drug-fuelled youths roam the countryside. Leonardo was a famous writer and professor before a sex scandal ended his marriage and career. Heading north in search of her new husband, his ex-wife leaves their daughter and her son in his care. If he is to take them to safety, he will need to find a quality he has never possessed: courage.

Release date: July 5, 2012

Publisher: MacLehose Press

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Last Man Standing

Davide Longo

He looked out at the flat fields covered with low bushes where the road stretched into the distance, with occasional bends despite the fact that nothing seemed to be in the way to make them necessary. The sky was a monotonous unmarked grey for as far as he could see it, reminiscent in every way of the last few days.

A man appeared in the courtyard.

Leonardo watched him slowly make his way to the cars and walk round them, peering through their windows: he had a leather jacket and trousers with big side pockets. He could have been about thirty, with the compact physique of a rugby player.

Why not tonight? he thought, watching the man stop in front of the boot of his Polar.

The man took a screwdriver or knife from his pocket and with a simple movement flipped open the boot.

For a few seconds he studied the jerry cans inside as if trying to work out what might be in them, then unscrewed the cap of one and sniffed. When he was quite sure of its contents he replaced the cap, grabbed a can, closed the boot, and went away just as he had come.

Leonardo let the curtain fall back and went to the bedside table where he had put his water bottle. Taking a sip, he sat down on the bed. He could hear steps from the corridor, and the noise of something with wheels being pushed towards the stairs.

That evening he had hesitated for a long time before deciding whether to leave the cans in the car or take them to his room, but after thinking the matter over for a long time he had come to the conclusion that all in all he had done the right thing, or at any rate the least wrong thing, and that if the cans had been in his room it would have been worse.

He went into the bathroom, took his washbag from the shelf and put it into the holdall he was packing on the bed. He stowed the vest and pants he had been wearing before he showered in a side pocket, then slipped on his jacket and went out of the room, leaving the key in the door as he had been told to do.

Passing down the corridor he glanced at the pictures on the walls: dead pheasants on big wooden tables, baskets of fruit and pewter pots. There was the still the pervasive odour of boiled vegetables he had noticed the previous evening, and after the rain that had fallen in the night the fitted carpet smelt of damp undergrowth.

An elderly woman was clutching the handrail on the stairs. When he asked her if she needed help, the woman, wrapped in a most unseasonable tailor-made wool costume, looked at him with total indifference as though he had been nothing more than the sound of a closing door, then turned her face to the wallpaper. Leonardo apologized, pushed past her and went on down to the hall.

The surroundings, despite their gesso statue, artificial plant and carpet covered with cigarette burns, had clearly had quite a different appearance only a short time before. He could see marks where shelves and brackets had been roughly stripped from the walls, and big lead pipes ran the length of the ceiling. The door to the courtyard was protected by a heavy grille, through which the cars and the entrance gate were visible. Occasional circles were spreading in the puddles, and he could sense that the air was already heavy and sultry.

“Have the dogs been bothering you?” the man behind the counter asked without looking up from the papers spread in front of him. He was no longer wearing the green sweater he had had on the previous evening when he had demanded payment in advance and shown Leonardo how to use the hot-water token for the shared bathroom.

“There are packs of dogs all round the enclosure at night. We’ve tried poisoning them, but it doesn’t help.”

Leonardo watched him sign a paper in a sloping hand. His shiny head looked as if he were in the habit of greasing it with fat and polishing it with a woollen cloth every morning. A lot of postcards showing places which were now inaccessible had been clipped with clothes pegs to the metal frame of a bed propped against the wall behind him. On the counter you could still see where objects, now vanished, must once have stood. One space looked as if it might once have held a computer. A telephone had survived, even if no longer attached to any cable.

“I think something’s missing from my car,” Leonardo said.

The man turned to detach a couple of fuel tokens from the metal net and copied their code numbers into a register. When he had done this he took a pack of cigarettes from his shirt pocket and lit one. He took a puff and looked at Leonardo through the smoke.

“Are you sure?”

“Yes.”

“Certain?”

“Absolutely.”

The man dropped ash into a saucer with a picture of a saint on it. He had a leather armband round his wrist and his right ear looked as if it had been chewed. Leonardo imagined these two facts must be connected in some obscure way which would have required time to work out.

“The guard was in the watchtower all night,” the man said. “No-one could have got into the enclosure.”

“Yes, I’m sure that’s true.”

The man studied Leonardo’s thin face and long, mostly grey, hair. He was probably reflecting that the man before him did not work with his hands and was physically inactive.

“Then you must suspect the other guests,” he said.

Leonardo shook his head.

“No, not at all.”

The man took in Leonardo’s frank gaze, then puffed out his cheeks as if this would help him to think. His eyes were the colour of glass bottles that had spent years in a dark cellar.

“Denis!” he shouted loudly, then picked up his cigarette from the edge of the saucer and bent his bald head over his papers again.

A moment or two later a door opened behind him and the lad Leonardo had seen in the courtyard emerged.

“My brother,” the man behind the counter said without looking at either of them. “He looks after security.”

Seen close up, the lad looked younger than thirty. He had thick wool stockings and the side pockets of his trousers were full of short cylindrical objects.

“This gentleman says something’s missing from his car,” the bald man said.

The boy considered the tall body and narrow shoulders of Leonardo in his linen jacket, as if bewildered by a utensil which must have once been useful but had now become obsolete.

“I was on guard all night,” he said, “and we haven’t opened the gate yet this morning.”

There was no shadow of defiance on his face. Only the boredom of someone compelled to go once again through an over-familiar rigmarole.

“I don’t doubt that,” Leonardo said, “but I also know that someone’s forced open the boot of my car.”

“What have you lost?” asked the boy.

“A can of oil.”

“Motor oil?”

“No, olive oil.”

“Was it the only one you had?”

“No, I had four.”

The boy was silent, as if all possibilities had been covered. His brother stopped writing.

“If you like, we can call the police.”

Leonardo thought about it.

“How long would they take to get here?”

“We use a private security firm and they don’t much like to be called out. Once we had to wait two days.”

Leonardo looked at his own hands pressing on the desk: they were long, thin and emaciated. The man continued to stare at him.

“Maybe you only had three cans and are making a mistake,” he said.

Looking up, Leonardo saw the boy’s back disappearing through the door he had come in by.

“I’m glad we were able to sort out this misunderstanding,” the man said, lowering his bald head over the counter. “You’ll find breakfast in the dining room.”

The room Leonardo entered had been divided by a plasterboard partition, from the far side of which kitchen and laundry noises could be heard.

The old lady Leonardo had met on the stairs was sitting at the table nearest to the door, while a fat man of about forty breakfasted by the window. He was apparently a commercial traveller, with two black cases leaning against either side of his chair. On a round table in the middle of the room were a pot, two Thermoses, some bread, a few cups, a rectangular block of margarine and a bowl of jam of unappetizing colour. A clock on the wall showed ten past eight. No staff could be seen.

Leonardo poured himself a cup of coffee and took it to one of the three free tables. He put his bag down and took a sip: real coffee diluted with carob.

It reminded him of a conference on the circularity of Tolstoy’s writing many years before in Madrid, and the dinner that had followed at a restaurant whose unmarked entrance had seemed like the way in to an ordinary block of flats. The chairman had been forced to spend the whole evening dealing with invective hurled by his wife against enemies of bullfighting. Most of those present must have been used to the woman’s heavy drinking and aggressive defence of this spectacle outlawed only a few months earlier by the government, and they seemed not to be bothered by it. Then, at the end of the evening, with the restaurant nearly empty, a young woman – probably a student in the company of some lecturer whose more or less official mistress she was – had sung a song she had written in which she maintained that love was nothing more than a means to an end. None of those present had either the strength or enough reverse experience to contradict her. The coffee they had then drunk, each imprisoned in his or her own guilty silence, had been like the coffee he had before him now, except that at that time you could still find decent coffee everywhere.

As he lifted the cup to his lips again Leonardo became aware that the old lady was looking at him. He nodded to her, but she continued to stare without responding. Her sparse hair had been built up into a gauze-like structure through which light weakly filtered from the skylight. Her fingers were covered with jewels and everything in her appearance seemed calculated and tense in some way about which it might almost have been blasphemous to speculate.

Leonardo took a book from one of the side pockets of his holdall and leafed through it till he found the story he was looking for.

It was a story he had read many times since the age of twenty-two, and for which he had always felt unconditional love. Both in moments of utter despair or fierce hope the story had always adapted itself to his mood, revealing itself for what it was: a perfect piece of design. He had always advised his students to read it, both those with literary ambitions and those who imagined that a man in his position must be able to offer them useful pearls of practical wisdom. Many years had passed since the last time anyone had expected any such thing from him, but if it ever happened again, now or in years to come, he was certain that his answer would have been the same: A Simple Heart, he would have said.

When he had finished reading Flaubert’s description of Madame Aubain, for whom Felicité was so ably performing her duty, he took another mouthful of coffee and it tasted better. The sun had come out in the courtyard and through the window he could see it reflected from the car windscreens. The incident of the oil can seemed remote and thus of little significance.

“I’ll be home by this evening,” he told himself.

Raising his eyes for a moment as he turned back to his book, he met those of the old lady, who had silently approached him.

“Please sit down,” he said, removing his holdall from the free chair.

The woman skirted the short side of the table and sat down. The skin between the few deep creases on her face seemed strangely young and taut. She had carefully outlined her lips with deep scarlet.

“I’m sure no-one has recognized you,” the lady said.

Leonardo shut his book. The woman nodded severely.

“I couldn’t fail to. You’ve been one of the great delusions of my life.”

“I’m sorry.”

“I was so naïve. I spent years in the arts and should have realized better than anyone the huge gulf between the artist and the shabbiness of the man.”

Leonardo took a mouthful of coffee.

“What was your own field in the arts?”

The woman checked the architecture of her hair with her left hand.

“Opera. I was a contralto.”

Leonardo complimented her. The man at the other table was watching them; his heavy hands restless, the rest of his body motionless. Leonardo imagined he must be having ignoble thoughts.

“May I ask you a question?” the woman said.

“Please do.”

“After what happened, did you continue writing?”

“No, I stopped.”

The woman screwed up her eyes, as if reliving one of many memories.

“I could not sing for nearly two years when my daughter was born because of her health problems. I nearly went mad. And I don’t say this out of empathy with you. The situation I found myself in was very different from yours. I had done nothing wrong.”

Leonardo finished his coffee.

“Then you started again?”

“Of course,” the woman exclaimed. “One engagement after another. Not many contraltos can boast of singing till the age of fifty-two, but I had a voice other women could only dream of. I was on stage two days after I lost my son. Have you any idea what it means to lose a son and two days later find yourself singing Rigoletto in front of a thousand people?”

The fat man got up from his table and passed them on his way out.

“Goodbye,” the woman said.

“Goodbye,” he answered.

Leonardo followed the man with his eyes as far as the door. Rembrandt without the beard, he thought.

“An arms dealer,” the woman said. “Stays here two nights a month.”

Leonardo would have liked more coffee.

“Do you come here often?” he asked.

“I’ve been living here for a year. If that’s not often, I don’t know what is.”

The sound of the commercial traveller’s car attracted their eyes to the window. He manoeuvred his luxury off-road vehicle and went out through the gate which was being held open by the man from reception. The two acknowledged each other, then the bald man closed the gate and padlocked it, slung his rifle over his shoulder and slowly walked back.

“His car’s bulletproof,” the woman said. “That’s why he’s able to come and go as he pleases.”

Leonardo nodded and removed some perhaps nonexistent speck from his shoulder.

“Where did you live before you came here?” he asked.

“In P.,” the woman said. “But when this business with the outsiders started, my daughter persuaded me to move in with her. After a few months my son-in-law was called up for the National Guard and my daughter decided it would be safer to move to Switzerland. So I told her to go and find a house, then come back for me. She knew this place and brought me here so I’d be alright in the meantime.”

The old woman said no more, as if that was the end of the matter. Leonardo smiled weakly.

“Will you be staying here much longer?”

The woman gave him a sharp look.

“Where else should I go?”

“But I thought your daughter was waiting for you in Switzerland.”

“She’s not in Switzerland anymore,” the woman said, removing a crumb from the table. “When her husband died, she married again, a German. Now she lives in Germany. She has suffered, but for the better: her first husband was an inconsistent man. He died at V., so far as we can understand from whoever writes those official letters. But the one she has now seems a lot better, altogether another kettle of fish.”

“Why don’t you join her?”

The woman looked at him as if he had just wet himself.

“Don’t you ever watch television? Have you no idea what’s happening? When the lines were still working, my daughter used to call me every day and beg me, I’m not exaggerating, beg me to let her come and fetch me. But I always said no. That it wasn’t worth the risk. I’m ninety-two, I lack for nothing here, and she’s the only child I have left. You have a daughter too, if I remember rightly?”

Leonardo lifted the cup to his lips, regardless of the fact that he had finished his coffee.

“Yes.”

“Does your wife allow you to see her?”

“No. I haven’t seen her for seven years.”

“So I thought.”

For a moment they studied different corners of the room in silence.

“Now I must get on with my journey,” Leonardo said.

“Where do you live?”

“At M.”

“Is that the village where The Little Song of Tobias the Dog is set?”

“Yes.”

“So you’ve gone back to your childhood home?”

“Yes.”

They heard a horn. A small tanker had stopped in front of the gate. There were two men in the cab.

“Not that I wish it for you,” the woman said, “but perhaps sooner or later you’ll want to start writing again.”

Leonardo smiled and shook his head. They watched the bald man open the gate and the driver bring the lorry into the courtyard. Once out of his cab, the driver put on work gloves and attached a thick ridged pipe to the tank while the bald man opened a manhole cover fastened to the ground by two locks. Both men had a pistol in a holster under their jackets. Leonardo stared at the ochre countryside and a sky the colour of curdled milk.

“I really must be on my way,” he said.

He picked up his holdall. The woman fixed her eyes on the yellowing lily of the valley in the centre of the table and waited till he had reached the door before calling him by his surname.

“The best possible interpretation is that you did something stupid,” she said. “But no-one can ever forgive you for what you did.”

Leaving the hotel, he drove north on the same secondary roads as he had come by. The autostrada would have saved him several hours, but he had heard of fake checkpoints at which travellers were robbed, and for this reason he preferred a less obvious route well away from the larger towns.

He drove with the window down, the hot, clammy wind filling his shirt; from time to time he took a mouthful of water from the bottle beside him. Since starting out three days before he had passed about a dozen cars and several military convoys. The villages he passed through were mostly deserted, with only an occasional old man sitting in a doorway, a boy on a bicycle, or the face of a woman drawn to her window by the sound of the car.

About noon he stopped to fill up with petrol. When he sounded his horn a man came out through the gate to the service station while another stayed in the doorway with his rifle lowered. Leonardo got out of the car, let himself be searched and said how much petrol he wanted. The man, who might have been about fifty, and wearing a rock band T-shirt, got into the Polar and drove it into the enclosure. Leonardo tried to check through the grille how much was being put in, but the back of the car was hidden by the prefabricated hut where the two men lived, and where a young woman with dark skin and curly hair was leaning out of a window. Leonardo imagined she must be tanned from working all summer in the open, unless she was an outsider who had got in before they closed the frontier.

The man in the T-shirt brought the car out again.

“See you later,” Leonardo said as he paid.

“Take care,” the man said, turning away.

Leonardo pulled over a couple of kilometres after the service station. Before getting out of the car he had a look round. The countryside was flat and the yellow grass, mostly unmown, was bending over in the hot wind. A long way off was a hut and the ruins of what must once have been a kiln for making bricks. Then a line of mulberries and some electric pylons disappearing into the distance in the direction of an almost invisible group of houses.

Leonardo listened to the silence for a while, then got out of the car and checked that the cans were in place. He opened them and sniffed to make sure the contents had not been replaced while the car was being filled up, then he closed the boot and mopped the sweat from his forehead with his handkerchief. He became aware of an acid stench of decomposition.

He looked into the ditch separating the road from the fields. There was a dog lying in it, its belly swollen, a swarm of flies whirling round its eyes and open mouth. A black labrador killed by another dog or poisoned.

He was about to turn back to the car when he heard a whimper.

A few metres from the dead dog the ditch disappeared into a small tunnel no wider than a bicycle wheel. He understood at once what was going on.

He returned to the car, started it and moved off. He switched on the radio, but the preset came up with nothing, so he switched it off again and drove for several kilometres without slowing down until he was forced to stop at a crossroads.

Checking to make sure that there was no other car with right of way, he noticed a group of men not far off in a field. There were six of them, armed with rifles, and they seemed not to have noticed him: two were using a long pole to explore the ditch that bordered the field, while the others were following them with their eyes on the grass.

Leonardo put the car into gear to drive on but, as he engaged the clutch, six, ten, perhaps twenty dogs jumped out of the ditch the men were searching and all began to run in the same direction. Taken by surprise, the men hesitated, then started yelling and shooting at the tapering shapes racing through the grass. The dogs had almost reached a water channel that would have given them protection, when, for no apparent reason, they turned at right angles so offering the wider target of their sides to the hunters. Leonardo saw one or two roll over in the grass, others vanish as if swallowed up by a hole, yet others explode into reddish puffs of air. Then the shooting stopped and the men spread out to comb the field. An occasional isolated shot followed, then total silence.

Leonardo realized his foot was still on the clutch. He put the car in neutral and took his foot off. The engine struggled, but did not stall.

The men went back to the irrigation trench from which the dogs had come. Leonardo saw some of them go down into the ditch and throw out what looked like small soft bags full of earth. After a few minutes there must have been about thirty of these, piled in a heap.

Then the men scattered across the field and dragged the carcasses of the dogs towards their puppies, and when this was done one of them took a can from his knapsack and poured the contents over the heap.

Leonardo closed his eyes, his chilled sweat-soaked shirt sticking to his chest. When he opened his eyes again a column of black smoke was rising in the air. He stared, paralyzed, for a few moments with the acrid smell of burned fur coming into the car through the window, then he engaged the gears and did a U-turn. Moving away, he thought he could see in his rear mirror the men waving their arms to attract his attention, but he continued to accelerate.

He recognized the place near the ruins of the kiln. He drew up and, while dust from the verge of the road enveloped the car, he went to the ditch. Lowering himself in, he slithered down it until he was lying on his face in the earth, a few centimetres from the dog’s carcass. Disgust forced an inarticulate sound from him and when he touched his bare arms he realized they were dirty with yellow slime. He wiped them on his shirt, got up and walked quickly to where the tunnel passed under the road.

No sound was coming from inside it; all he could hear was his own laboured breathing and the rapid beating of his heart.

Bending down he looked inside. The tunnel was blocked by filth, stones and refuse brought by the water. But nothing moved or made any sound. He smacked his lips. There was no response.

Leaping up again he checked the road: the pyre was no more than a couple of kilometres away and he could not be certain the hunters would not follow him.

Kneeling down he stuck his head into the tunnel and thought he saw a movement. He reached in, and as if he had been breaking a membrane, was struck full in the face by the smell of death. Suddenly what he was doing seemed just as incomprehensible to him as when, years before, after one of his books had just reached the bookshops, he had been unable to explain to himself how he had spent three years of his life writing a complicated poem in a difficult and antique verse form, which many of his readers, and most of his critics, had already dismissed as an affected minor work.

He lay face down on the ground so as to be able to stretch out an arm, but also because his twisted position was making his head spin. His hand touched something soft and cold. Pulling it towards him, he saw it was a dead puppy covered with ants. He threw it behind him near to the body of its mother and when he heard the thud as it hit the ground he retched, as if his gesture had validated the existence of a hidden part of himself that had now emerged into the light with pangs like childbirth.

Reaching into the tunnel again, he felt something tepid and let it slide across the palm of his hand like a baker collecting a loaf from the far end of the oven.

He pulled the puppy out. It instinctively hid its muzzle between his fingers. It must have been the first time it had seen the light. It was wet with urine and yellow liquid had dried round its half-closed eyes. Leonardo climbed out of the ditch and sat down in the shadow of the car. Grabbing his water bottle from the seat he took a long drink, poured some water into his hand and tried to wash his arms and neck, then tried to get the puppy to drink from his hand, but the animal seemed stunned by sleep or hunger and did not react. Even when he cleaned the incrustation from its eyes, the dog continued to keep them closed. It was black and its ears were hanging sideways, giving it an air of resignation.

He put it down long enough to take off his shirt and stretch it over the seat. He settled the dog on top and was about to get into the car when he was stopped by a sudden pain in the pit of his stomach. With long strides, his naked thin torso marked by large moles, he ran towards the edge of the road, and was only just able to drop his trousers in time before a gush of diarrhoea emptied him.

Gasping for breath and bent double, he got back to the car door and took a toilet roll from the inside compartment. He wiped himself carefully, wetting the paper with a little water.

Sitting down in the driving seat, he took a casual shirt with horizontal brown stripes from his bag, and began searching on the map for a road that would help him avoid the crossroads where the pyre would certainly still be burning. He found one that would not take him too far off course: it was a case of going back about ten kilometres and crossing the river. His wristwatch said a quarter past three. To the north blue mountains closed the horizon. By eight it would be dark, but if he couldn’t get home by then at least he would be on a familiar stretch of road.

He drove slowly, taking great care at corners as if his new passenger must not be disturbed. The dog never moved, and every now and then Leonardo reached out a hand to check its little heart, which beat rapidly under his fingers. Towards five it urinated, and when the light started to fail, it began lolling its head and emitting little blind whimpers. Leonardo stopped the car and cleaned its eyes which were encrusted again, then held a piece of the cheese he had eaten for lunch to its mouth, but the dog seemed not to recognize it as eatable and turned away in irritation.

He went off to urinate in the shelter of a clump of acacias, then got back into the car, put on his jacket because the air was getting fresh, and took the dog in his arms.

He looked down at the plain from the height of the first foothills. With the dying of day the sky had cleared and now the sun was sinking behind the mountains, the vault of heaven a deep unshaded cobalt.

It won’t eat and tomorrow it’ll be dead, Leonardo thought, holding the dog close.

Far off the lights of A. and one or two other villages were shining softly, with the lights of some factory prominent among them. For several months now the minor roads had no longer been lit, the football league championship had been suspended, and the television closed down after the evening news at ten, not starting again until the news at ten the following morning.

He smiled at the swarm of lights and the beauty of several fires burning on a hillside to the east. The dog’s breathing had relaxed and the heat of its body through his shirt was warming his chest; it had the smell of things which are new to the world and still have no name. Like the smell of a birthing room or a cellar where cheeses ripen. Or a paper mill. A smell of transition.

“I won’t give you a name,” he said, stroking the puppy’s head with his finger.

When he arrived in the square the church clock was striking eight.

He opened the door of the hardware shop. Elio looked up from a newspaper he must have salvaged from some packaging. The last newspaper had reached the village four months before. Leonardo went to the counter and put down the two cans he had brought in, then wiped his brow

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...