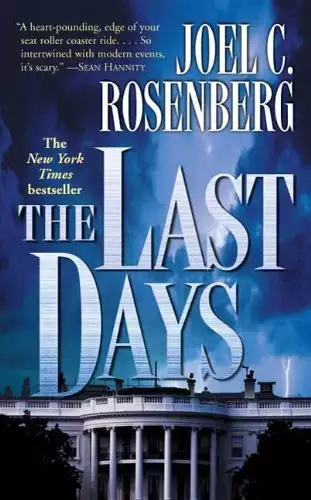

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Osama bin Laden is dead. Saddam Hussein is buried. Baghdad lies in ruins.

Now the eyes of the world are on Jerusalem as Jon Bennett—a Wall Street strategist turned senior White House advisor—his beautiful CIA partner Erin McCoy and the U.S. Secretary of State arrive in the Middle East to meet with Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat.

On the table: a dramatic and potentially historic Arab-Israeli peace plan, of which Bennett is the chief architect. At the heart of the proposed treaty is the discovery of black gold deep underneath the Mediterranean—a vast and spectacular tract of oil and natural gas that could offer unprecedented riches for every Muslim, Christian, and Jew in Israel and Palestine.

With the international media closely tracking the story, the American message is as daring as it is direct: Both sides must put behind them centuries of bitter, violent hostilities to sign a peace treaty. Both sides must truly cooperate on drilling, pumping, refining, and shipping the newly found petroleum. Both sides must work together to develop a dynamic, new, integrated economy to take advantage of the stunning opportunity. Then—and only then—the United States will help underwrite the billions of dollars of venture capital needed to turn the dream into reality.

Release date: August 3, 2010

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Last Days

Joel C. Rosenberg

"You really want me to kill him?"

The question hung in the air for a moment, and neither said another word.

The flames crackled in the fireplace of the elegant penthouse apartment overlooking central Tehran. Light rain fell on the clay balcony tiles. Bitter December winds howled outside, rustling trees and rattling windows. Thunder rumbled in the distance. And the room and the sky grew dark.

Mohammed Jibril looked out over the teeming city of his youth, as the haunting call to prayer echoed across the rooftops. He knew he should not feel so tired, but he did. Tired of sleeping in different beds, different houses, different cities. Tired of constantly watching his back, and that of Yuri Gogolov, the man sitting in the shadows behind him, puffing casually on one of his beloved Cuban cigars. Jibril considered his options. There weren't many.

"You understand, of course," Jibril continued, "that you will be unleashing a war that could escalate beyond our control—beyond anyone's control?"

A silent, unnerving pause.

"And you're ready for this war?" Jibril asked, perhaps too bluntly.

Instantly regretting the question, he could feel a chill descend upon the room. Gogolov sat motionless in an overstuffed velvet chair. He looked out at the mountains and the minarets and the twinkling lights of the ancient Iranian capital. He drew long and hard on the Cohiba, and the cigar glowed in the shadows.

Air Force One roared down runway 18-36 "Lima."

Flanked by four F-15E Strike Eagle fighter jets, the gleaming new Boeing 747 quickly gained altitude and banked toward the Atlantic. President James "Mac" MacPherson stared out the window. He could no longer see the lights of Madrid Barajas International Airport, or the lights of the Spanish capital itself, just nine miles away. The emergency one-day NATO summit was over. In a few hours, he'd be home, back at the White House, under pressure to answer the question on everyone's mind: Now what?

Osama bin Laden was dead. Al-Qaeda and the Taliban were obliterated. And now—just three and half weeks after it began—the war in Iraq was effectively over. Saddam Hussein was dead and buried under a thousand tons of rubble. His sons were dead, too, cut down in a hail of allied gunfire. His murderous regime had been toppled. His henchmen were being scooped up by U.S. Special Forces, one by one, day by day. But the president had never felt more alone.

Rebuilding Iraq and keeping it from blowing apart like Bosnia would be difficult enough. But that wasn't the only thing on his plate. Wars and rumors of wars dominated the headlines. New threats surfaced constantly. North Korea was just months away from building six to ten nuclear bombs. Iran would soon complete a nuclear reactor with Russian assistance, capable of producing two to three nuclear warheads a month. Syria and Iran appeared to be harboring top Iraqi military officials and scientists. NATO was badly divided. The U.N. was a mess. Democrats threatened to filibuster most of the White House's major legislative priorities. And now this: the FBI and Justice Department were recommending the death penalty in United States v Stuart Morris Iverson, one of the most chilling acts of espionage in the nation's history, not to mention one that involved one of the president's closest friends and a man who was, until a month ago, Secretary of the Treasury.

Saudi Arabia, meanwhile, was insisting that all U.S. forces leave its soil immediately. And OPEC—outraged by the U.S. strikes against Iraq—was threatening an all-out oil embargo unless war reparations were made to the Iraqi people and pressure was brought to bear on Israel to allow the creation of a Palestinian state. The president recoiled at the thought of an ultimatum from countries he had just saved from nuclear, chemical, and biological annihilation. He wasn't about to submit to blackmail, but he was painfully aware of the risks he was running. Even now, his handpicked diplomatic team were on their way to Jerusalem.

MacPherson—feeling quite vigorous at sixty until a team of Iraqi assassins nearly took his life the month before—was beginning to feel his age. He swallowed a handful of aspirin and washed it down with a bottle of water. His head was pounding. His back and neck were in excruciating pain. He needed sleep. He needed to clear his head. The last thing he needed was an oil price shock reminiscent of '73. So much of the road ahead was foggy. But one thing was painfully obvious: the horrific battle of Iraq wasn't the end of the war on terror. It was just the beginning.

* * *

When ordering a hit, Jibril preferred the anonymity of an Internet café.

No one would bother him. No one could trace him. And at less than 25,000 rials an hour—about three U.S. dollars—it was far cheaper than using his satellite phone.

Tehran alone boasted more than fifteen hundred cyber shops, which had exploded in popularity ever since Mohammad Khatami was elected president in 1997 and gave the fledgling Internet sector his blessing. The hard-line religious clerics continued to be wary. In 2001, they'd forced four hundred shops to close their doors for operating without proper business licenses, breaking Islamic laws and trafficking in "Western pollution." They'd insisted that the government deny anyone under the age of eighteen from entering the shops. But that just made the idea of an electronic periscope into the West all the more alluring, and Web traffic shot up faster than ever.

The bulletproof sedan eased off the main boulevard. Mohammed Jibril told his driver to drop him off at the Caspian Cyber Café on Enghelab Avenue, across from Tehran University. A moment later he logged on, and sent a half dozen cryptic e-mails. Next, he pulled up the home page for Harrods of London and quickly found what he needed. "Harrods Chocolate Batons with French Brandy—twelve individually wrapped milk chocolate batons filled with Harrods Fine Old French Brandy. Made from the finest Swiss chocolate. 100g." He hit the "buy now" button, typed in the appropriate FedEx shipping information, paid with a stolen credit card, and left as quickly as he came. Now all he could do was wait, and hope the messages arrived in time.

* * *

The eyes of the world were now on Jon Bennett.

A senior advisor to the president of the United States, Bennett was the chief architect of the administration's new Arab-Israeli peace plan. The frontpage, top-of-the-fold New York Times profile the day before—Sunday, December 26—had just dubbed him the new "point man for peace." The media was now tracking his every move and the stakes couldn't be higher.

The president was eager to shift the world's attention from war to peace, to rebuilding Iraq and expanding free markets and free elections in the Middle East. The Pentagon and CIA insisted the next battles lay in Syria and Iran. But the State Department and White House political team argued such moves would be a mistake. It was time to force the Israelis and Palestinians to the bargaining table, to nail down a peace treaty the way Jimmy Carter did with Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat at Camp David in '77, and the way Clinton tried to do with Barak and Arafat in the summer of 2000. "Blessed are the peacemakers," they reminded the president. And the president was listening.

Bennett wasn't so sure it was the right time, or that he was the right man. He hadn't asked to be named "point man for peace." He hadn't wanted the job. But the president insisted. He needed a deal, he needed it now, and Bennett couldn't say no.

At forty, Jonathan Meyers Bennett was one of the youngest and most successful deal makers on Wall Street, and a guy who had everything. An undergraduate degree from Georgetown. An MBA from Harvard. A thirty-eighth-floor office overlooking Central Park. A forest green Jaguar XJR, for business. A red Porsche turbo, for pleasure. A seven-figure salary, with options and bonuses. A seven-figure portfolio and retirement fund. A $1.5 million penthouse apartment in Greenwich Village near NYU, for which he'd paid cash. Closets full of Zegna suits. And Matt Damon good looks.

Few people on Wall Street knew much about this shadowy young man, but he was the talk of all the women in his office. Six feet tall with short dark hair and grayish green eyes, he had a picture-perfect smile after a fortune in dental work as a kid. He'd once been voted the office's "most eligible bachelor," but only part of that was true. He was a bachelor, but not all that eligible. He dated occasionally, but all his colleagues knew Bennett was married to his work, pure and simple. He typically worked twelve to fourteen hours a day, including Saturdays. None of that had changed at the White House, and now he was at his desk by ten-thirty on Sundays, too, watching Meet the Press and planning for the week ahead.

Before coming to Washington, Bennett was the senior VP and chief investment strategist for Global Strategix, Inc., one of the hottest firms on the Street. Part strategic research shop, part venture capital fund, GSX advised mutual and pension funds, as well as the Joshua Fund, which had $137 billion in assets under management. Over the years, GSX had become known as the financial industry's "AWACS"—its airborne warning and control system—able to alert money managers of trouble long before it arrived. GSX also had a reputation of finding "sure things," early investments in start-up ventures that hit the jackpot and paid off big. Most of the credit went to Bennett. He had a sixth sense for finding buried treasure, and he loved the hunt. The plaque on his desk said it all: "I'm not the richest man in the richest city in the richest country on the face of the globe in the history of mankind. But tomorrow is another day."

Then "tomorrow" threw him a curve ball. Suddenly he was off the Street, out of GSX, working for the White House, and on the Secretary of State's 757, headed for the Holy Land. It was surreal, to say the least, but the package came with one big incentive: the chance to cut a deal they'd be writing about for decades, and Bennett was determined to see it through.

"Hey there, Point Man, we there yet?"

Erin McCoy rubbed the sleep from her eyes. She put her seat back in its upright position and prepared for landing. A senior member of Bennett's team for the past several years, she'd been teasing him about the Times profile for the last twenty-four hours, and enjoying every minute of it. After takeoff from Andrews, she'd persuaded the pilot to welcome the entire American delegation, including "our own Jon Bennett, the esteemed point man for peace." She'd even plastered the interior of the plane with big red, white, and blue signs asking, "What's the point, man?"

"You kill me, McCoy."

"Don't tempt me, Jon." She smiled.

Bennett stared back out the window, trying to ignore how good McCoy looked in her ivory silk blouse and black wool suit. She really was beautiful, he thought. Why hadn't she become a model instead of joining the CIA? She was five-foot-ten with shoulder-length chestnut brown hair, lightly tanned skin, sparkling brown eyes, and a picture-perfect smile that hadn't required any dental work at all. All that, and she was ranked an "expert marksman" with six different kinds of weapons, including her favorite, a 9-mm Beretta, which she carried with her at all times. How could this girl still be single?

"Just give me a copy of the schedule, would you?" Bennett asked.

"You got it," said McCoy as she pulled out a few pages from her briefing book. "Point Man touches down at 0700 local time, Monday, December 27th; meets with the Palestinians; then the Israelis; saves the world; spends New Year's in Cancun; then cuts large check to beautiful deputy for saving his life, and his job."

Bennett fought hard not to give her the satisfaction of a smile. But it wasn't easy.

"I don't know what I'd do without you, McCoy," he said, snatching the pages from her hands. "But believe me, I'll think of something."

The Web master in London instantly recognized the e-mail address.

This was no order for chocolate. And she knew it was urgent. She quickly e-mailed a copy to Harrods' shipping clerk downstairs for immediate processing, then logged onto AOL and IM'd a gift shop on the Rock of Gibraltar.

* * *

Thirty minutes later, they sped along Highway One toward Jerusalem.

Through driving rains. Past huge green road signs in Hebrew, Arabic, and English. Past the rusted shells of armored personnel carriers destroyed in the 1948 war. Past roads that would lead them, if they wanted, a few miles and a few thousand years away to ancient biblical towns like Jaffa and Bethlehem and Jericho.

Two blue-and-white Israeli police cars led the way. Two more brought up the rear. In between were a jet black Lincoln Town Car carrying the advance team from the embassy, two bulletproof Cadillac limousines, two black Chevy Suburbans carrying heavily armed agents from the State Department's Bureau of Diplomatic Security, and four vans of reporters who would beam the historic words and images to a global audience desperate for some good news from the war-torn Middle East.

The first limousine—code-named Globe Trotter—carried the Secretary of State and his aides. Bennett and McCoy rode in the second limo—code-named Snapshot—joined by two old friends upon whose wisdom they now greatly counted. The first was Dmitri Galishnikov, the hard-charging CEO of Medexco, Israel's fastest-growing oil and gas company. The second was Dr. Ibrahim Sa'id, the soft-spoken, Harvard-educated chairman of PPG, the Palestinian Petroleum Group, which had made a fortune in the Gulf and now had everyone in the West Bank and Gaza buzzing with excitement.

"Miss Erin, I must say, you look like an angel—like my wife on our wedding day," Galishnikov boomed. "As for you, Point Man, you look like hell."

That got a laugh from everyone, even Bennett.

"Seriously, how are you feeling, Jonathan?" Sa'id asked. "We were worried about you. It's a miracle that you're alive, much less here."

It was a miracle. The last time they'd been together, they'd been under attack by Iraqi terrorists. Bennett took two AK-47 rounds at point-blank range. He'd practically bled to death before being airlifted to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany. Three weeks of recovery and rehab later, he was still not 100 percent.

"Good days and bad, you know." Bennett shrugged. "But it's good to see you two again."

"You, too, my friend," Sa'id agreed. "And your mother? How is she?"

McCoy watched Bennett shift uncomfortably.

"Well, she's not exactly thrilled about me coming back, that's for sure. Dad's heart attack, the funeral, what happened to me—she's been through a lot. But she's hanging in there. I'll head down to Orlando to see her for a few days when we get back."

"That's good." Sa'id smiled. "You're a good son, Jonathan."

Bennett wasn't so sure about that, but he said nothing.

* * *

An e-mail arrived in a small gift shop on Gibraltar.

It was quickly forwarded to a wood-carving shop in Gaza. Soon it drew the attention of an immaculately well-dressed young man by the name of Khalid al-Rashid. To anyone but him, the message would mean nothing, just an old family relative sending greetings for the holidays. But to the third most powerful man in Palestine, it could only mean one thing—his date with destiny had arrived.

* * *

The motorcade began to climb the foothills leading to Jerusalem.

That night, the U.S. delegation would take up two entire floors of the King David Hotel, overlooking Mount Zion, the stone walls of the Old City, and the Mount of Olives just beyond them. Tomorrow, they'd have a long working lunch with Israeli prime minister David Doron. But soon, they would actually be sitting in Gaza City, overlooking the stormy Mediterranean, drinking coffee and eating baklava with Palestinian Authority chairman Yasser Arafat, and his hand-chosen, silver-haired successor, Prime Minister Mahmoud Abbas, better known by his nom de guerre Abu Mazen.

It would be a long day. Diplomatic formalities and endless pleasantries would likely take until lunch. They'd eat lentil soup and lamb until they couldn't stuff down another scrap of pita. Then they'd get down to business.

At the heart of the proposed treaty was the discovery of black gold deep underneath the Mediterranean—a massive and spectacular tract of oil and natural gas off the coasts of Israel and Gaza that could offer unprecedented wealth for every Muslim, Christian, and Jew in Israel and Palestine. And the American message they were about to deliver was as daring as it was direct: both sides must put behind them centuries of bitter, violent hostilities to sign a serious peace agreement. Both sides must truly cooperate on drilling, pumping, refining, and shipping the newly found petroleum. Both sides must work together to develop a dynamic, new, integrated economy to take full advantage of this stunning opportunity. Then—and only then—the United States would help underwrite the billions of dollars of loan guarantees needed to turn the dream into reality.

Bennett's "oil for peace" strategy was controversial, to be sure. It shifted the discussion from simple "land for peace"—long the central premise of fruitless diplomacy between the Israelis and Palestinians—to a shared vision of economic growth and wealth creation. Secret polls commissioned by the White House found 63 percent of Palestinians in favor of the idea, though 71 percent opposed U.S. military action in Iraq. More troubling: 14 percent of Palestinians—the hard-core Islamic militants—vowed to stop the American peace process at all costs.

The key was Yasser Arafat. He'd repeatedly hailed the discovery of petroleum off Gaza as "a gift of God to our people" and the basis of "a strong foundation for a Palestinian state." But the big question remained: was the isolated and aging Arafat—at eighty-one, now in the cold, cruel winter of his life—finally ready to make peace with the Jews? On that, the jury was still out. But that's why Bennett and his team were there.

* * *

Khalid al-Rashid was born on June 6, 1967.

It was the day the shooting started, a struggle the Jews called the Six Day War, and the Arabs called Al-Nakbah—"The Disaster."

Raised in an apartment over a woodworking shop on the outskirts of Gaza City, al-Rashid was no maker of tourist trinkets. That was his father's work, before he was gunned down by Israeli soldiers during the first intifada, the Palestinian uprising against Israeli occupation, in February of 1988. The son had risen through the ranks of Force 17, Arafat's Fatah security apparatus—first as an errand boy, a driver, then a bodyguard, and now Arafat's personal security chief.

It was al-Rashid who now ensured the survival of Arafat from all threats, foreign and domestic. It was al-Rashid who handpicked Arafat's security team, grilled them, trained them, and either rewarded or punished them for their loyalty to him, and to the cause of liberating all of Palestine from the River to the Sea. And though the Israelis and Americans were not yet able to prove it beyond a reasonable doubt, it was in fact al-Rashid who for years had personally selected and then paid the family of each suicide bomber who slipped across the Green Line into an Israeli coffee shop or pizza parlor or bus station or elementary school to blow themselves up, kill as many Jews as possible, and deliver themselves into the arms of Allah.

But this was different. Now, with the Secretary of State and U.S. delegation en route from Jerusalem and the whole world watching, al-Rashid sat in his father's home, thinking the unthinkable.

* * *

Ahead of the motorcade lay the Erez Checkpoint.

The Gaza Strip. No-man's-land.

Here in a sliver seven miles wide and twenty miles long lived more than a million souls—half under the age of fifteen—and the population would double over the next decade. Six in ten men were unemployed. Most families lived in refugee camps amidst unimaginable squalor. The Strip was a breeding ground for radical Islam and volcanic hatred of Israelis and Americans that could erupt in a firestorm at any moment—without warning—and often did.

The motorcade slowed. Bennett's heart beat a little faster. Jittery Israeli soldiers, their M-16s locked and loaded, opened the steel barricades and guided them past concrete bunkers, guard towers, searchlights, and barbed-wire fences. Border guards in Humvees and army Jeeps mounted with heavy machine guns watched their every move. It was an eerie experience. For they were leaving Israel proper and entering the most dangerous and densely populated hundred forty square miles on the face of the earth.

* * *

Secretary of State Tucker Paine took Bennett's call.

Bennett wanted to brief him on his conversations with Ibrahim Sa'id, and Paine needed to sound interested. Paine didn't appreciate the New York Times profile that made Bennett, not Paine himself, appear the mastermind of this deal. He felt quite sure his unattributed quotes had done their appropriate damage, reminding Bennett who was in charge. But he also had to watch his step. The president trusted Bennett a great deal, and the last thing Paine needed was more trouble from the Oval Office.

Indeed, Tucker Paine had been dispatched for this delicate mission precisely because he could truthfully tell Arafat how vehemently he had opposed the president's decision to attack Iraq. Who better to win a hearing with Arafat than a Secretary of State who'd almost been fired for his heated opposition to the president's policy of "regime change," a policy that had left Baghdad in ruins and the Atlantic alliance in tatters.

Time was running out.

But al-Rashid couldn't think clearly. He knew what they wanted. It was something he'd considered for months. But the implications were enormous.

The American, after all, was bringing a death sentence for the Palestinian revolution. Did he think they could be bought off? Had the Americans no idea what this revolution was all about, what fueled these fires? Why not simply destroy this infidel and send the world a message. Surely that was a cause worth dying for, was it not? And yet, who was more culpable—the infidel, or the betrayer?

How could he do it? How could he even consider this meeting? How could he even consider cutting a deal with these devils? How could he betray the martyrs—the blood of al-Rashid's own father—now, of all times, with their brothers decimated in Baghdad? For what? To make the Palestinians rich? To let their sons become fat and happy? To let their daughters grow up to drink Starbucks and listen to Britney Spears and shop at Victoria's Secret? Again al-Rashid glanced at the e-mail. He knew what the answer must be. He could not merely send little girls to do the cause of justice. It was time to be a man. It was time to do the job himself.

* * *

The motorcade roared through Beit Lahiya.

Uniformed policemen of the Palestinian Authority—commonly referred to as the PA—manned checkpoints at every major intersection. But it hardly made Bennett feel more secure. The PA was arguably the most dysfunctional pseudogovernment on earth. It remained Yasser Arafat's private fiefdom. The security forces operated at his pleasure. If Arafat said you were safe—and meant it—you probably were. If not, you'd be advised to stay as far away as possible. So "supplementing" the Palestinian police presence were heavily armed American DSS agents, strategically positioned along the way. Not since President Clinton's visit to Gaza in December 1998 had security been this tight. Anti-American sentiment was running high. But so, too, were hopes that a Palestinian state might not be so far off.

* * *

They gathered in the White House Situation Room.

National Security Advisor Marsha Kirkpatrick and White House Chief of Staff Bob Corsetti drank coffee and watched the live coverage. From a Fox camera positioned on the roof of a hotel near the PLC headquarters, they could see the motorcade coming down Salah El Din Street, packed with crowds spilling into the road despite the metal barricades and hundreds of Palestinian security forces set to work a double shift. A moment later, they could see the motorcade turn onto Omar El Mukhtar Street, past the Great Mosque on the right and the Welaya Mosque on the left.

Just past Jumal Abdel-Nasser Street, the motorcade finally turned into the gates of the PLC's executive compound, past a dozen Palestinian flags snapping in the winter winds. A CNN shot from the roof of the Rashad Shawa Cultural Centre across the street showed the vehicles pulling into a huge courtyard. Two new five-story glass-and-steel administrative buildings stood to the left and right. Each was connected to an impressive three-story legislative headquarters upon which towered a thirty-foot gold dome. The entourage pulled into the compound's semicircular driveway, and parked behind huge, waist-high concrete barriers designed to minimize—if not fully prevent—the prospect of Israeli tanks driving straight into a cabinet meeting and obliterating the Palestinian Authority. DSS agents jumped out of the last Suburban. They took up positions around the secretary's limousine and ran a sector check.

"Globe Trotter is secure," lead DSS agent Doug Lewis told his team.

"Blueprint, secure."

"Fog Horn, secure."

"Perimeter One, secure."

"Perimeter Two, secure."

"Rooftop team leader, we're secure."

"Snapshot, secure."

"Roger that, we're good to go."

* * *

Agent Lewis stepped out of the lead limousine.

He opened the door for Secretary Paine, code-named Sunburn for his nearly albino complexion. The secretary was immediately greeted by a blinding flurry of flashbulbs and questions. The secretary simply smiled and waved. Bennett got out of his car and watched Paine button his Brooks Brothers coat, straighten his red silk power tie, and begin walking across the courtyard to center stage, trailed by Lewis and two more DSS agents. It was quite a walk—almost forty yards to the front steps of the legislative building, past three marble fountains and a huge bronze replica of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem.

Following strict protocol, Bennett, McCoy, and the others would hang back and wait for the statesmen to shake hands and go inside before joining them. Over the hood of the limousine, Bennett could see Arafat emerging from the front door in a wheelchair—flanked by Prime Minister Abu Mazen with his distinctive silver hair, silver mustache, and wide-rimmed glasses.

Arafat's wheelchair was being pushed by his ubiquitous security chief, Khalid al-Rashid. What struck Bennett first was how small Arafat looked—just five foot four—and how old he looked, even from a distance. His thinning gray hair was combed back over his head, but largely covered by his trademark black-and-white checkered kaffiyah. He'd lost weight. His pale, gaunt face wore a day's worth of stubble—why bother shaving for the Americans?—and his lower lip and his hands shook slightly from the onset of Parkinson's disease.

Forbes magazine said Arafat was worth a cool $1.3 billion. It seemed hard to believe. For the first time, Bennett was actually glad to be there. He found himself fascinated by this feisty, frail, strange little man in olive army fatigues, a man who for five decades had captured headlines the world over.

Mohammed Yasser Abdul-Ra'ouf Qudwa Al-Husseini.

A.k.a. Yasser Arafat.

A.k.a. Abu Amar.

Born August 24, 1929, in Egypt, or—he claimed—in Jerusalem.

Founder of Fatah in 1956.

Head of the PLO since 1969.

A 1994 Nobel Peace Prize winner who somehow had never actually made peace.

* * *

With Abu Mazen at his side, al-Rashid gently lowered Arafat's wheelchair.

He maneuvered down the front steps and reached inside his coat pocket to make sure it was still there, hidden by his stocky build and thick Italian leather coat.

It was an odd moment—indiscernible to anyone but a professional—but even from a distance it caught the eye of Erin McCoy and Donny Mancuso, Bennett's lead DSS agent. Why would a security chief of al-Rashid's stature be pushing his principal's wheelchair? Why not let a bodyguard do that job while al-Rashid stayed a few steps back, surveying the scene? And why take his hand, even for a moment, off Arafat's wheelchair as he lowered it down a few steps?

Al-Rashid quickly withdrew the hand from his pocket, and again placed it back on the handle of the wheelchair. A chill rippled down McCoy's spine. Instantly suspicious, she glanced over to Mancuso, wondering if he'd seen the same thing. But then, what exactly had she seen really? And what was she supposed to do about it? Was the Secretary of State and their team really in danger of being shot at by Yasser Arafat's personal security chief? Here? In front of the international media? The whole notion was ludicrous. She was becoming a little paranoid on her first trip to Gaza, McCoy thought—too much history, too many briefings. She tried to drive it all from her mind and stay focused. But she couldn't. It wasn't a rational thought she was processing. It was instinct, and hers were rarely wrong.

* * *

It was gray and wet and cold.

Yet beads of sweat were forming on al-Rashid's forehead and upper lip. Do I wait for the secretary to cross the courtyard? Do I wait until after Arafat greets him? Or would that just provoke a devastating U.S. attack against Palestine? Look what the Americans have just done to Iraq. Is now the right time? Is this the legacy I want to bring upon my family, my people? And yet…

Arafat began coughing violently in the damp air. Al-Rashid stopped pushing the wheelchair and again reached into his coat pocket. McCoy and Mancuso tensed as the secretary finished crossing the huge co

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...