Chapter One

It has been my experience that when homeowners take the time and trouble to permanently seal off a room, they usually have a Very Good Reason. And typically, that means something about that room is Very Not Good.

So when my foreman, Mateo, announced that the attic of my new house had a sealed-off closet with a window, I found it hard to keep the tone of my voice casual.

"Sealed off?"

"Yeah," said Mateo. "The original blueprints indicate a good-sized closet with a little window under the eave. You can see the outline of the window from the outside if you look closely, but the whole thing seems to have been closed up at some point."

I reminded myself not to jump to conclusions. This was a marvelous old house. Dating from 1911, it featured the master woodworking and built-ins that typified the Arts and Crafts movement, combined with the original architect's artistic flair of Moroccan arches and intricately paned windows. The first time I walked in the door, I experienced a rush of dŽjˆ vu that was highly unsettling, but later, I came to understand it had been sparked by a psychic and emotional connection with my late mother and her memories of living here as a very young child. Overall, the house's vibes were good-in fact, fantastic. Warm, loving, embracing, just like my mother.

If some erstwhile resident had, say, set up a sacrificial altar in a sealed-off attic closet, surely I would have felt it by now, wouldn't I? After all, what good is it being a ghost-talking psychic home renovator if I can't suss out the presence of evil in my own darned house?

"Well, I guess it wasn't 'sealed off,' exactly," continued Mateo. "A big armoire was placed in front of the door."

"An armoire in front of a door could simply mean there wasn't enough wall space in the attic," I said, relieved. It wasn't as though there were cinder blocks or something permanent blocking access.

"Sure," said Mateo. "Maybe the closet was where they stored things they only needed once a year, like Christmas ornaments."

"Exactly," I said.

We looked at each other, then looked away.

My fiancŽ, Landon Demetrius, and I were hip deep in an extended remodel of this beautiful and rather good-sized house in Oakland, across the Bay from San Francisco. Many decades ago, my great-grandparents had owned the home for a while, and my mother had lived there for a few years when she was a child.

When Landon discovered I had a special connection to this stunning-but terribly faded-grande dame, he had purchased it for us upon our engagement in a sweeping romantic gesture. Which was swell, but . . .

My father has a saying: "There's nothing like an extended remodel to ruin a relationship."

Bill Turner is my dad and the founder of Turner Construction, and when it comes to renovating historic buildings, he's the best in the business. Since Dad (semi) retired, I'm now running Turner Construction, so it's fallen to me to moderate the frequent, and often contentious, "discussions" among our clients about everything from floor plans to choice of low-flow toilet to the precise level of sheen in the paint in the downstairs entry.

And true to Dad's adage, more than a few relationships go down in flames because the couples can't agree on how to remodel their damned house.

With the arrogance of one who hasn't experienced something firsthand, I used to believe that going through a home remodel was a relationship litmus test: If a couple couldn't handle being together without a working kitchen or a functioning bathroom, found it just too much to live surrounded by noise and dust and chaos for months or years on end, or couldn't navigate the million and one decisions that had to be made-not to mention wrestling with budget overruns and clashing tastes-then how in the world could that couple expect to face the stresses inherent in a long-term relationship?

Except now I was one half of a renovating couple's "discussion," and I was on the verge of losing it.

The crux of the problem, at least as I saw it, was that I, the professional home renovator with years of construction experience, had certain ideas about what I wanted, and what the house needed, while Landon, a math professor who had never even picked up a paintbrush, had very different and, in my view, stupid ideas.

This morning's argument circled around whether to install period wallpaper borders in the living room. Landon didn't want to use the gorgeous William Morris designs I had suggested because of the appalling history of wallpaper manufacturing in nineteenth-century England, whose use of poisonous dyes had blinded many of their workers.

"They don't blind their workers anymore," I said through gritted teeth.

"I'll think of it every time I look at that border," responded Landon.

"I have a lot of experience in this sort of thing, you know," I said for the thousandth time.

"I understand, and I respect that immeasurably," he said in that laudable but at times annoyingly formal way of his. "But I must insist that it is I, after all, who bought the house."

"So you want to make this about money? Really?"

"Of course not. You know I don't care about that."

"Besides, I thought you bought it for us."

"I did, indeed. And it will be ours just as soon as you marry me. When will that be, did you say?"

For someone as measured and perpetually pleasant as Landon, this was a highly snide conversation. But he had a point: I hadn't exactly settled on a marriage date. Being engaged suited me quite well, but actual marriage still scared the hell out of me. I had tried it once and it hadn't ended well.

"The wallpaper-versus-painted-border discussion can wait a while," Mateo said in a casual but firm tone. Mateo's in-charge demeanor was at odds with his small stature; apparently he had decided to take on the role of mediator. "The plasterwork isn't even finished yet."

"But that's my point," I insisted. "We would need a different level of finish, depending on whether we're planning on paper or paint. Also, the genuine Morris paper has a long lead time-I want to get it ordered as soon as possible."

"I agree with Mateo; we should table this discussion for the moment," said Landon.

"Have you decided whether you want to repair the walls with the original lathe and plaster or with drywall?" asked Mateo.

"Plaster," I said.

"Drywall," Landon said at the same moment.

Our gazes locked, and not in a romantic way.

"Ooookaaaay," said Mateo, who was not a stupid man. "Howsabout you two take some time and talk that one out? In the meantime, want to check out that attic closet situation?"

"This sounds like your department," said Landon to me, as he checked his watch. "And I must leave now or risk arriving late to class."

"Your class doesn't start for another hour," I pointed out.

Landon was teaching a graduate theoretical physics seminar at UC Berkeley, which was a twenty-five-minute drive from where we were in Oakland. I was an on-time kind of person, myself, but Landon was irritatingly so, blaming it on the unpredictable traffic in the Bay Area. "Better to be safe than sorry," he would say cheerfully as we sat in the car in front of a friend's house for a quarter of an hour so as not to catch our dinner host stepping out of the shower.

"Better safe than sorry," Landon said now, right on cue. He smiled and gave me a little squeeze. "This is looking great, Mel. Everything's on track, eh? We'll figure out the wallpaper thing, not to fret."

I managed a smile. It's just a decoration, I reminded myself.

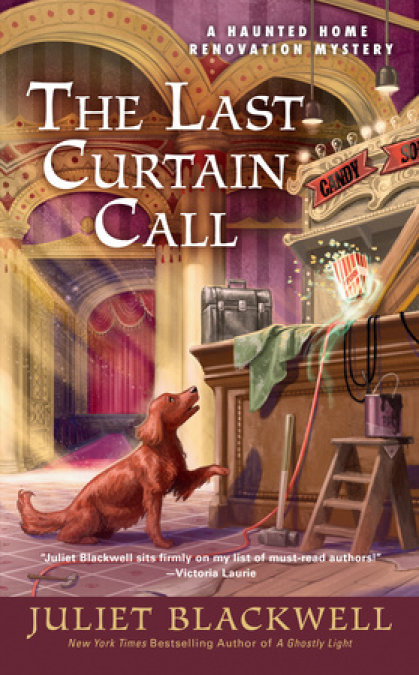

"And good luck at your meeting later," Landon said, leaning down and kissing me good-bye. "The Crockett Theatre, yes? Let me know how it goes."

"The great old theater in San Francisco?" asked Mateo. "I stopped by there last time I was in the Mission. I always heard that place was haunted."

An uncomfortable silence descended.

My experience with ghosts tended to bring conversations to a standstill, rather like discussing a tendency toward flatulence in polite company. The meeting this afternoon was to discuss Turner Construction taking over the renovation of the old-style movie theater. The previous contractor had abruptly dropped out halfway through the project, citing an "unforeseen scheduling conflict," but I suspected something else was afoot. I was familiar with the century-old Crockett Theatre and its reputation for being haunted because not only do I run a construction company, but I'm also something of a ghost buster.

And, apparently, a glutton for punishment.

"Be that as it may," said Landon as he gave me a quick hug and took a brief moment to gaze into my eyes. "See you tonight. Promise me you'll be careful?"

I nodded and watched as Landon picked his way through a maze of two-by-fours and sawhorses and compressors, politely wishing a good day to each member of the Turner Construction work crew as he passed. Landon was tall and broad-shouldered, with slightly long brown hair and a trimmed beard. He wore his usual outfit of tan khakis, a crisp white shirt, leather boots, and his favorite old-fashioned jacket, which was long with a high collar. The first time I saw him, I could have sworn he was a Civil War-era ghost. Landon had grown up in both the US and England, spoke with a vaguely British accent, and had made a pile of money from some computer-related doodad that I still hadn't wrapped my mind around.

And he was mine. Sort of.

Remember to breathe, Mel.

"Shall we check out the attic?" asked Mateo as he started up the broad central staircase, pausing on the landing, whose massive window offered a gorgeous view of the street and the hills of Oakland.

I grabbed my toolbox and followed him. In the upstairs hallway, Mateo pulled down the little trapdoor in the ceiling, folding out the ladderlike stairs to the attic.

Something went bump overhead.

Our eyes met.

"Yeah. That happens, occasionally," said Mateo. "Don't see any sign of rats up there. Probably a squirrel on the roof, something like that."

Mateo swiftly climbed the ladder into the blackness of the attic, and switched on the light.

I took a moment to repeat the mantra my acupuncturist had given me, then started climbing, feeling pleased with myself. Not long ago, after nearly falling to my death from the very high roof of a mansion in Pacific Heights, I had developed a fear of heights-which is no small problem when one's bread and butter is the construction business. I still became dizzy if I looked down, and I avoided climbing out onto rooftops whenever possible. The acupuncture therapy was not a miracle cure-something Dr. Victor Weng reminded me of at each treatment-but I was making progress. Slowly but steadily.

Exhibit A: I could now climb a ladder to an attic without fainting-carrying my big toolbox in one hand, no less.

Baby steps.

The attic was partly finished, and the roof's gables were angled so sharply that I had to duck in some areas. Several of the reaches under the eaves had been made into storage closets, and the whole space was packed full of furniture, tchotchkes, and assorted boxes from previous residents: framed pictures, magazines, a very old radio, books, a Close-n-Play record player, a stack of old LPs.

After the most recent owners had passed away, the house had stood empty for a couple of years due to probate issues, and Landon had bought it "as is."

This was another bone of contention between us: Landon advocated tossing everything into a dumpster and "starting with a clean slate," whereas I insisted on going through it all first. Who knew what treasures might be found among the historic detritus in these boxes? A reasonable person didn't just toss a genuine Close-n-Play record player.

It was the classic "junk"-versus-"antiques" debate.

"Has someone been smoking up here?" I asked, catching a whiff of tobacco.

"Not on my watch." Mateo shook his head. "No smoking on the jobsite, as you know: Turner Construction rules."

"My dad, maybe?" Bill Turner was known to sneak a smoke or two, and none of the crew was willing to rat him out. He wasn't officially-or regularly-on the job anymore, but as the founder of Turner Construction, he still showed up from time to time, whenever he felt like it, and pretty much wrote his own ticket.

"Haven't seen him lately," said Mateo, sniffing exaggeratedly and tapping his nose. "Gotta say, Mel-I don't smell anything, and I've got a good sniffer. It's pretty musty up here. Maybe that's it? Anyway, here's the armoire."

The large oak wardrobe wasn't the fancy European kind that graced the pages of interior design magazines, more a large but serviceable storage unit. I peered into the small gap behind the armoire and spied the closet door.

"How did they get this armoire up that ladder in the first place?" I asked.

"Back in the day, big pieces of furniture were often made so they could be taken apart, brought up piece by piece, and reassembled," said Mateo.

"Why bother?"

"Like you said, probably needed more storage space." One side of his mouth kicked up. "Unless, of course, they were trying to keep something in that closet. Ever see Rosemary's Baby?"

"Very funny." I encountered enough weird stuff in my daily life; I didn't need Mateo encouraging such thoughts.

"Want to take a look inside?" Mateo asked.

"You know I do."

Mateo and I had worked together for years, and we shared a strong streak of curiosity. As a young man, he had done a short stint in prison for a nonviolent drug offense, and when he was paroled, my dad had given him a chance to prove himself on the jobsite. For the past decade, Mateo had been a loyal and reliable employee. When Turner Construction's much-cherished foreman, Raul, obtained his contractor's license and set up his own shop, Mateo took over as the boss of our crew. He had married and now was a very proud father of an adorably chubby baby. There wasn't anyone I would rather have heading up my home renovation.

Taking up positions on either side of the heavy armoire, we coordinated our movements-"One, two, three, heave!"-and together managed to shove the heavy cabinet far enough away from the wall to allow us to inspect the closet door.

"What do you think?" I asked Mateo.

He shrugged. "Nothing special about it, so far as I can see. Its twin is on the opposite side of the attic."

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved