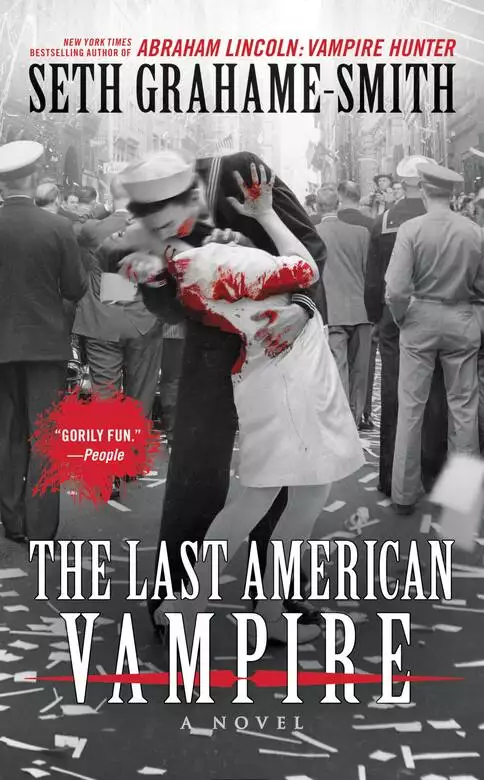

The Last American Vampire

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

New York Times bestselling author Seth Grahame-Smith returns with the follow-up to Abraham Lincoln, Vampire Hunter—a sweeping, alternate history of twentieth-century America as seen through the eyes of vampire Henry Sturges.

In Reconstruction-era America, Henry is searching for renewed purpose in the wake of his friend Abraham Lincoln’s shocking death. It will be an expansive journey that will first send him to England for an unexpected encounter with Jack the Ripper, then to New York City for the birth of a new American century, the dawn of the electric era of Tesla and Edison, and the blazing disaster of the 1937 Hindenburg crash. Along the way, Henry goes on the road in a Kerouac-influenced trip as Seth Grahame-Smith ingeniously weaves vampire history through Russia’s October Revolution, the First and Second World Wars, and the JFK assassination.

Expansive in scope and serious in execution, The Last American Vampire is sure to appeal to the passionate readers who made Abraham Lincoln, Vampire Hunter a runaway success.

Release date: January 13, 2015

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Last American Vampire

Seth Grahame-Smith

—Abraham Lincoln, in a journal entry, December 15th, 1832

I was dying, and I wasn’t afraid.

After all, I’d asked for this. I’d asked him to bring me as close to death as a man could get. Close enough to see the stitching that holds existence and inexistence together, without actually tearing it. And here I was, perched on a high wire above Hades, nine toes in the grave and the tenth on its way, and all was well and right. I’d heard it said that a certain peace washes over us when we stray close enough to death. That our bodies release chemicals to calm us, to ease us into the inevitable nothing that drapes us all in its black cloak sooner or later. Perhaps that’s all it was—a biological calmness. Or perhaps I just trusted that Henry knew what he was doing.

A thought rang through the dark, bright and pleasing, like a church bell on a cold, starry night. If I do die tonight, I thought, at least I’ll die in October. That most American of months, when the first wisps of chimney smoke kiss the crisp apple air, and the promise of a World Series looms large in the imaginations of the good and ever-hopeful people of New England. When children have finished mourning the long summer and grown re-accustomed to the buzzing fluorescents of their classrooms. When Christmas is beginning to take shape on the horizon, just beyond the cousins and food comas of Thanksgiving. Closer still are the masks and glow sticks and cotton spiderwebs of Halloween, the one night when we embrace the darkness from which all of America is descended. October is the gateway to the wonderful, mystical finale of the American year. A place where life ends and the celebration of life briefly begins.

I began to taste blood in the back of my throat. Fear suddenly crept in, cold and unwelcome, tracking mud on the carpet of my cozy little death. I looked into Henry’s eyes just before my own began to roll back in my head. Those black vampire eyes that I’d seen only once before, years earlier. He’d shown them to me, those eyes, along with the hideous glass shards of his fangs and the calcified razors that were his claws. He’d shown me because he’d needed me to believe the impossible. His face had been wild then. Animal-like. But tonight it was careful and curious. The tips of his fangs were barely visible beneath his upper lip. His right hand was on my throat, squeezing off my jugular, cutting off the blood to my brain. My brain, in turn, was carrying out its final instructions, ticking boxes on the pre-death checklist that humans have evolved over eons. And all because I’d asked him to.

Perhaps I’d misjudged Henry. Perhaps this ancient, powerful vampire—whom I’d come to think of as a friend—meant to kill me after all. I felt like a zookeeper who wanders into a tiger’s cage, unafraid, only to be mauled to death. Why? he thinks, as he’s torn apart by those massive claws and teeth. How can this be, when I raised you, fed you, loved you since you were a helpless cub? Only in the final, terrifying seconds does he understand that the love he gave was never returned. That he’d grown too close. Too familiar. I forgot that it was a tiger, he thinks as he slips away. It was always a tiger.

The edges of my vision went fuzzy… darkness creeping closer to the center of my sight, like those ever-tightening black circles at the end of silent movies and cartoons. I tunneled away into the dark, but there was no light at the end. No feeling of floating above my body. There was only the inner. The quiet. I thought of all of the Halloweens and Thanksgivings and Christmases I would miss. I thought of my boys, when they were so small and helpless I could hardly stand it.

And then there were no more thoughts.

It had begun with a jingle, years earlier. A chime that had been affixed to the front door of the five-and-dime since the universe was in its infancy and time just a concept in God’s imagination. Its ring was as old and as quaint as the store itself—a store that had been a fixture in the little upstate town of Rhinebeck, New York, since 1946, selling damn near anything to damn near anybody: school supplies, knitting yarn, toilet brushes, toys, rain boots, electrical sockets, and whatever else customers were willing to plunk down their pocket change for. Packed onto shelves against wood-paneled walls, or in bins lined with contact paper.

I’d worked there on and off since I was fifteen, earning extra money for college, brimming with big dreams and big ideas, dreams of published novels and Manhattan book signings, of tenured professorships and corduroy blazers with elbow patches. College had come and gone, novels begun and abandoned, vows exchanged, children born, struggles endured, and there I was, behind that same counter, fifteen years and twenty-five pounds later, and not an inch closer to Manhattan than I’d ever been. There I was, thirty years old, greeting customers by name, watching the Yankees on a small color TV under the counter, selling pink pencil erasers and sink stoppers for a penny’s worth of profit, from eight-thirty in the morning until five-thirty at night, six days a week. Every week. Wash, rinse, repeat. There I was, clinging to the idea that there was still a place for an old five-and-dime in a Walmart world—still a chance that all those scraps of paper with their half-begun stories would congeal into a dream realized.

By 2006, I’d heard that door jingle a million times. But one summer day, it seemed to ring with a slightly darker sound as a new customer stepped in from the sunshine of East Market Street and onto the checkered linoleum of our floor. I looked up from the sports section of the New York Post and saw a young man of twenty-seven or so, with dark, fashionably messy hair. Expensive clothes designed to look tattered and cheap. Dark sunglasses, which he neglected to take off. I’d seen plenty of his kind before—the weekend visitors who drive up from the city to revel in the quaint and backward ways of us simple folk. The young urbanites who brave the Taconic Parkway to ironically spend their discretionary income. But this was no visitor, it turned out. He was a local boy. Not born and bred, but transplanted.

“Hello,” I said, the way one does in a small town.

“Hello,” said Henry, and went about his browsing. And that was that. I went back to my newspaper, not knowing that I had just been nudged an inch closer to Manhattan.

Henry came in from time to time, bought things, and left. This went on for a number of months, before we slowly evolved beyond the required pleasantries and started talking. Music, mostly. Henry was always eager to talk about music, and I was always happy to oblige. Other than writing, it was the closest thing to a passion that I had, as evidenced by the ever-evolving iPod mix that filled the store’s speakers from open to close, its tracks culled from the deepest recesses of “you haven’t heard of this band yet” blogs. We talked about what we were listening to, gave each other recommendations, and so on. Henry’s taste ran the gamut: the Beatles, Boards of Canada, Stockhausen, Count Basie, Sebadoh, Chick Corea, the Doors, Captain Beefheart, Stravinsky, Sunny Day Real Estate, Elvis, Alice Coltrane, My Bloody Valentine, Patsy Cline… he was a one-man “staff recommends” shelf at a failing record store. I liked him instantly.

Months passed, seasons changed, and life went as it usually did—which is to say, nothing of much note happened, until one evening, in the winter of 2008, the bell jingled, and Henry hurried into the store carrying a package wrapped in brown paper. A package containing a bundle of ancient letters, a list of names and contact information, and ten ancient-looking leather-bound journals, each one filled with tightly packed handwriting.

They were the personal journals of Abraham Lincoln, chronicling his lifelong battle against the vampires that had shaped his destiny and long haunted the American night.

Right. Of course they were. I didn’t believe a word of it, just as I don’t believe in flying saucers or Santa Claus or happy endings. There were no such things as vampires, let alone ax-wielding vampire hunters who went on to become president of the United States. Henry, anticipating this, had seen fit to convince me that night in a shocking way that left me badly shaken. Once you’ve seen those glassy fangs, those pulsing blue veins, and the satiation of that bottomless hunger for blood, there’s little room left for doubt.

So began nearly two years of research and writing, poring over the journals and letters, chasing down the names on the list he’d given me, and conducting interviews with reluctant subjects. I wrote day and night, much of it in notebooks at the store counter, stopping only when a customer needed help. I’d been given the gift of a story that had already been written. A story that just needed to be carefully stitched together, like the boundary between existence and inexistence. The scribbled notebooks became a typed manuscript, the manuscript became a book, and the book was given to the world to be judged. My dream had been realized in dramatic fashion. Or so I thought.

Writing a book, it turned out, wasn’t all that big a deal in the Twitter age. Certainly not as big a deal as which pop star got arrested or which reality TV personality got her prebaby body back. For one brief, shining moment, I was the ringmaster, and then, just as quickly as it had arrived, the circus packed up its tents and steamed on to the next town, and there I was, back behind the counter. A few inches closer to Manhattan, but still miles away. Living a life that suddenly felt two sizes too small.

The idea came in the winter of 2011.

It was a Monday morning, slow and snowy, the sidewalks empty, only the occasional car passing on the unplowed street, hazards flashing. The store was as dead as the world outside. I flipped through the pages of the Post, ignoring the chants of Egyptian uprisings coming from the mono speaker of my small television. One of the national morning shows was on, and news gave way to chat, gave way to weather, which was all I was really interested in. The weatherman forecasted—more snow, snow forever, endless winter—then read out the names and showed the pictures of those lucky viewers who’d reached their hundredth birthday. The chosen few who’d seen a century pass before their eyes, gone from horses and buggies to Mars landers in the blink of a lifetime. One of today’s celebrants was a man who’d reached the ripe old age of 108.

“My word,” said the weatherman. “Isn’t that wonderful? Imagine the things he’s seen.”

Imagine the things he’s seen…

I looked up from my paper. Something stirred in me—a vague memory of a passage from one of Abe’s journals. I couldn’t recall the words, not exactly, but I had the spirit of it. He’d written it as a young man, not long after training with Henry, wondering what it was like being a vampire, wondering what someone like Henry must have seen in his centuries. I went back through the transcripts of Abe’s journals on my computer (the originals were safely back in Henry’s possession) and found the passage I was looking for: “What a strange thing to be a vampire. To break free of death’s gravity!”

Abe’s journals had covered only a fifty-year span of Henry’s life. But what about the other four hundred years? What of a twenty-first-century man, born before Galileo or Shakespeare? Imagine the things he’s seen. A man who, with the exception of a brief and turbulent period of being alive, had never had a cold—or a gray hair?

That morning, I did something I hadn’t done in twenty years of working at the store: I closed early and braved the snowy roads to Henry’s house.

“Not interested,” he said.

His answer was immediate and unequivocal. For one, the last thing Henry wanted was more publicity. His fellow vampires had been upset enough when he’d shared the secret of Lincoln’s journals. Two, he saw no point in looking back. “Nothing kills a vampire as quickly as the past,” he said. To that end, he’d never kept a journal of his own. Never hung on to every letter the way Abe had. You have to keep moving, moving—make a point of staying engaged in the present. Otherwise you ended up like an old car, cautiously creeping along a snowy road with your hazards on. Still talking Beethoven when everyone else has moved on to Batman.

I persisted. He resisted. This went on for months. I would e-mail, and Henry would take days to reply. And when he did, he wasn’t encouraging.

Yes, I’m traveling. There’s nothing to discuss. I don’t see what good will come of me airing out my dirty laundry or further aggravating those of my kind who are already livid that I made certain details of our past public in the first place.

HS

From: @gmail.com>

Date: March 2, 2012 at 2:01:03 EST

To: @aol.com>

Subject: Book

Henry,

Are you traveling? I haven’t heard back from you regarding my last e-mail. I understand your concerns about privacy, etc., but I think there’s a way to get around those issues. Can we discuss when you return?

SGS

Finally, in the spring of 2012, more than a year after I’d first broached the subject, Henry agreed to sit and hear me out. We sat in the study of the giant metaphor that was his mansion—old and Gothic on the outside but completely redone on the inside, all concrete, iron, and glass. Open spaces and clean, tech-friendly surfaces, as if the very décor was there to strengthen his hold on the present. Nothing kills a vampire as quickly as the past. There we were, I with my take-out cup of Dunkin’ Donuts coffee steaming beside me, he with his hands folded in the lap of his expensive jeans. An incredibly old, experienced mind behind his clear brown eyes.

“So,” he said. “What did you have in mind—a rambling multicentury autobiography? A mopey treatise on the drawbacks of immortality?”

“I want to know what happened in Springfield,” I said. “After Abe’s funeral.”

I knew that being specific was the only shot I had. If I’d started with “Tell me everything,” or “Oh, whatever you feel like,” he would have disengaged. When you’re dealing with a man who has five centuries rattling around in his skull, you have to cast specialized bait or you’ll catch nothing. In the course of writing about the journals, I’d learned that Ford’s Theater hadn’t been the end of Abraham Lincoln. What I didn’t know was how he had escaped death… and what had become of him after he did. It seemed as good a place to start as any.

“How?” I asked. “How did it happen? How did you do it?”

Henry considered me with those old eyes. I could see his wheels turning, see him debating his next move. For a second, I wondered if I’d stepped over some invisible line, wondered if he was going to leap out of his chair and crack me open, spilling my innards onto the floor of his museum-quality home.

To my great relief, he started talking.

He talked until the days stretched into weeks and the summer became Indian summer, then autumn. And when the leaves of the Hudson Valley had reached the peak of their crisp, fiery bloom, we weren’t even close to the middle of the story. But we were hooked, and the experience had infused Henry with an energy that he hadn’t felt since the fighting times. He was intoxicated by the distilled memories that had been fermenting for hundreds of years. He was, in the words of Norman Maclean, “haunted by waters.”

I asked him questions. Sometimes I stopped him for clarification or elaboration. Mostly I just listened, taking notes and recording every word on my phone—both of us aware of, and amused by, the fact that we were living out a fictional scenario imagined by Anne Rice almost forty years earlier.

I spent the better part of a year conducting these infrequent but intense interviews. When Henry felt he’d rambled as much as he could, I began the task of transcribing months’ worth of fragmented recollections (excerpts of these transcripts appear on virtually every page of this book, as indented text), writing the connective tissue between them, and arranging it all into a palatable shape that would fit fashionably between two covers. I wrote about iron and electricity; rippers, Russian mystics, and Indian chiefs; I wrote about world wars and robber barons; about Roosevelts and Kennedys. Blood and murder and lost loves.

Henry gave me the freedom to change and “shine up” his description of certain things (he can be a very matter-of-fact speaker, even when describing the gory or fantastic). But I was strictly forbidden from changing a single word that might alter the truth of what was being told.

And what I was told, it turns out, is something of a caper. A manhunt spanning four centuries. A hunt for the greatest enemy America has ever faced, a shadowy puppeteer who seemed to confound Henry at every turn. Because of that, perhaps, there are some parts of Henry’s remarkable life that are simply not relevant to the larger tale and haven’t been documented in these pages. Another time, perhaps.

Between running the store and raising two resentful growing boys from a distance, it took me nearly a year to put together the manuscript in its rough form. When I was done, Henry set about making his own alterations—pulling back where he thought I’d gotten too colorful, pushing me when he sensed I was trying to be flattering or respectful. He insisted on naked judgment, warts and all.

One thing Henry found especially lacking were my descriptions of death. “They read like a eunuch writing about an orgy” is how he put it.

I asked him to describe it for me as best he could. I wanted to know what dying felt like in exquisite detail, so that I could convey that experience with my words.

“It’s impossible to explain,” he said. “You have to experience it.”

And so I asked him to kill me. And he obliged.

I shuffled down East Market Street, crisp leaves underfoot, the taste of blood clinging to my teeth like copper fillings. I had no memory of how I’d gotten there. One moment I was dead, the next I was in the center of town, the sun rising in a cold and cloudless sky, my feet guiding themselves down a well-worn path. In that rote, distant manner, they brought me back to the store, to the counter, to my notebook. In my fog, as the first customers began to trickle in, I wrote down everything I could remember, determined to capture the words before the high of being alive wore off.

Just as the towering myth of Abraham Lincoln—honest backwoods lawyer, spinner of yarns, righter of wrongs—tells only part of the truth, so, too, is the myth of America woefully incomplete. The country that Ronald Reagan once called “a shining city upon a hill” has, in fact, been tangled up in darkness since before she was born. Millions of souls have graced the American stage over the centuries, played parts both great and small, and made their final exits. But of all the souls who witnessed America’s birth and growth, who fought in her finest hours, and who had a hand in her hidden history, only one soul remains to tell the whole truth.

What follows is the story of Henry Sturges.

What follows is the story of an American life.

Seth Grahame-Smith

Rhinebeck, NY

October 2014

For God’s sake, let us sit upon the ground and tell sad stories of the death of kings.

—William Shakespeare, Richard II, act 3, scene 2

Abraham Lincoln wasn’t happy to be alive.

He’d been roused against his will, pulled from his well-deserved eternal rest with explosive force. One moment, he’d been floating gently through a borderless sea of warm, black nothingness. No more aware or burdened than a man is in the centuries before he’s born. And then some lesser god had yanked the plug out of the Great Drain of the Universe, and the consciousness that had once been Abraham Lincoln had been sucked down into it. He was born again. But not into the world outside.

The world of the inner welcomed him first. His brain remoistening with blood, one drop, one vessel at a time. One cell, two cell, red cell, blue cell. Synapses beginning to fire slowly, randomly, like the hammers of a typewriter striking a blank sheet of paper but spelling nonsense. Thoughts—what a strange concept, “thoughts”—being pieced together, the images and feelings primitive cave paintings on the inside of his skull. Then a filmstrip of disjointed frames flashing before him—what a strange concept, “him”—his mind gathering steam now, the fog of death lifting. Here, a dandelion in his six-year-old hand, his feet running across lush green grass. Here, the dirt hearth of a Kentucky cabin. Here, a candlelit book and the smell of bread cooling in the next room. A fleeting feeling of disconnected joy, then grief, then rage, coming and going at random as his brain emerged from its tomb. Each reanimated cell a speck of dirt being brushed off a long-buried fossil. The voices came next. Far-off words in some as yet foreign language. The cries of a child, echoing down a hallway. The moans of lovemaking.

Then, suddenly and unrelentingly, the nightmares. Horrific visions: the faces of his beloved children crying out as they burned away to ash. That ash swirling in a disembodied shaft of light as winged demons flew overhead, their skin so black that only their eyes and teeth showed. His son—the name… why can’t I remember his name?—reaching out for him, crying out as the impossible hands of the devil himself dragged him away to burn forever. The boy’s face streaked with tears, Abe helpless to save him. And then the nightmares broke like a fever, and Abe could breathe again. It was as if God had tired of watching him gasp and flop and had dropped him back in the cool waters of the now.

On the third day, Abe rose again. He heard a different voice beyond the darkness of his closed eyelids. Unlike the screams that had accompanied his nightmares, this voice came to Abe by way of his ears. It was a familiar voice, speaking words that were also familiar, though Abe wasn’t sure why. Nor was he certain what language the man was speaking, as those parts of the fossil had yet to be uncovered.

“Nothing in his life became him like the leaving it,” said the voice. “He died as one that had been studied in his death, to throw away the dearest thing he owed, as ’twere a careless trifle…”1

Abe’s eyes opened, though there was no life behind them. He looked around the room—that’s what it’s called… a room—as spare as a room could be. White walls. A fireplace at the foot of his large bed. A single, framed painting of a rosy-cheeked young boy hanging on the opposite wall. Yet as spare as the room was, there was also something vaguely familiar about it. A feeling of being home.

Abe noticed a shape to his right. A dark shape, hovering over him. A man, sitting in a chair beside his bed. There was something familiar about him, too. That face. That ghostly face framed by dark, shoulder-length hair.

The tiniest sliver of sunlight squeezed between the drawn curtains and fell on the wall above his head. Abe feared the light. He hated it. It blinded him. It burned him. He wanted it to go away, and it did. As if hearing his thoughts, the curtains were drawn shut, and the burning and blindness were gone.

Now, in the black pitch, Abe saw as never before. Every detail of the room revealed itself, as sharp as day, though drained of nearly all color. Every creak of the house was magnified by his ears. A mouse scurrying behind the walls became a horse galloping over cobblestones. The bristles of a broom sweeping a neighborhood sidewalk sounded like sheets of paper being torn an inch from his ear. And voices. Voices crashing ashore a hundred at a time, the result sounding quite like the jumbled din of an audience milling about in a theater lobby during intermis—

A theater. I was in a theater.

There were other voices—strange voices that didn’t pass his ears but were somehow heard just as clearly. Abe looked back to the man in the chair. With the sliver of sunlight gone, he was able to make out the features on the man’s face. It was the same face that had greeted him in his twelfth year—the first time he had been spared from the comforting embrace of death. He knew because it was exactly the same face. The face belonged to a man. The man who had steadied him when his body convulsed. Dried his skin when it ran with sweat. Who, now that Abe thought about it, had been right there, every time his fevered eyes had chanced to flitter open for a moment over the last days and nights. There was something so familiar about it all. Lying here in bed, with this man—this familiar man—by his side. Waking from a dream without end. They’d been here before, the two of them. What is your name?

And suddenly, like a ship enshrouded in fog catching the first faint sweep of the lighthouse beam, it came to him.

“Henry,” said Abe. “What have you done?”

Lincoln’s coffin is draped in black during a funeral procession in Columbus, Ohio—one of many stops made by the late president’s train on its journey to Springfield, Illinois. Henry would steal Abe’s body from the same coffin a few nights later.

Abe’s mortal body had died in the early morning hours of April 15th, but it was nearly a week before the late president’s funeral train departed Washington, D.C., on its way to Springfield, Illinois. The trip had taken thirteen days. Millions had turned out to mourn their fallen leader along the way, some waiting hours to shuffle past his coffin as he lay in state in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago, some lining the railroad tracks before dawn, hoping to get a glimpse of history as it sped by, to give a last salute to the savior of their Union as he journeyed home. By the time he was laid to rest on May 4th, Abe’s body had been an empty vessel for three weeks.

On that warm, sunny afternoon, Henry had stood among the thousands in Oak Ridge Cemetery, waiting through the speeches and the prayers in the shade of his black parasol. And long after the mournful masses had marched back to Springfield on foot and by carriage, Henry remained. He stood alone as hot day became warm night, keeping watch over the padlocked iron door of a receiving vault—the temporary home of Abe’s coffin, which he shared with the casket of his son Willie, whose body had been brought on the train from Washington so that it could be interred beside his father. Henry stood there, mourning his fallen compatriot, wading through the memories of their tumultuous forty-year friendship. He’d read some of the scraps of paper that had been left by passing mourners at the foot of the iron gates that surrounded the vault, along with flowers and keepsakes. One of the notes had stirred him like no other. A single scribbled line, taken from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar:

I am a foe to tyrants, and my country’s friend.

Henry had stared at those ten little words for the better part of an hour, his resolve deepening. Moments coming back to him as if rendered by the dreamy brushstrokes of Manet or Degas… Standing over Abe as a boy, pulling him from the clutches of death after his first ill-fated hunt. Standing in the woods outside New Salem, Illinois, trying to convince a young man who’d just lost his first love that the future held great things for him. Most men have no purpose but to exist, Abraham; to pass quietly through history as minor characters upon a stage they cannot even see. To be the playthings of tyrants. In the White House, the last time Henry had seen his friend, when the two of them had been at each other’s throats.

I couldn’t let it end that way. I imagined all the good that was left to be done. I imagined having the chance to finish what we’d begun. Even then, in death, I believed that it was his purpose to fight tyranny. And there was plenty of it left to fight, by God. To come so far—to bear the weight of a war on his shoulders, to pull a nation back together with his bare hands, only to be cut down at the hour of its splendid reunion. A hero who so often defied death in battle, only to have it ambush him in repose. This was a tragic ending worthy of Shakespeare. Yet unlike Shakespeare, I couldn’t find the moral in his death. Only senselessness. Waste. Looking back, I wonder what part my own guilt played in my decision. The fact that we’d parted on terrible terms. Perhaps all I wanted was a chance to make things right.

Whatever his reasons, Henry had broken into the tomb just before sunrise, and with no small effort, he’d spirited the body to a waiting carriage and then to a house on the corner of Eighth and Jackson Streets. Like many buildings and private homes in Springfield, it had been draped with black bunting as the city mourned its favorite son. But this house was different. A plaque beside the front door still read A. Lincoln.

I wanted it to be somewhere familiar, to ease the inevitable shock that comes with being pulled from eternal rest. It also had the added benefit of being sealed off for a period of official mourning—its shutters closed and heavy black drapes drawn inside. Darkness, privacy, and a sturdy bed were important whe

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...