- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

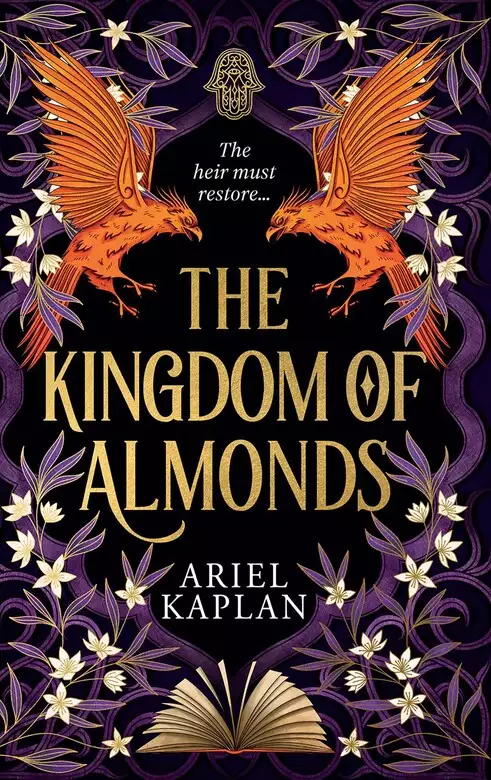

In the enchanting conclusion to the Mirror Realm Cycle, the fate of all three realms hangs in the balance as Toba, Naftaly, and their companions must settle the question of Luz once and for all. . .

Toba and Naftaly have stepped through the Gate of Luz into the mythic world of Aravoth, home to the Ziz, the bird of legend capable of raising the sea. Aravoth—the fabled third realm—is more dizzying and terrifying than Toba or Naftaly could have imagined. Nor had they expected to find someone already there, waiting for them.

After barely escaping the burning city of Zayit, Elena and the old woman have a new problem: Barsilay, heir of Luz, is being held for an exorbitant ransom by the paranoid Queen of P'ri Hadar. As Barsilay sits in his dark, demon-inhabited prison cell, he begins to realize the queen is guarding an ancient secret that might be the key to his release.

And the tyrant Tarses continues to close in on P’ri Hadar, wielding an army that spans the Mazik and mortal worlds and newly-powerful visions that reveal his most longed-for future—visions that he and Naftaly seem to share.

In this triumphant finale, the mirror realms must find their balance, or risk being lost altogether.

Publisher: Erewhon Books

Print pages: 560

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Kingdom of Almonds

Ariel Kaplan

She made mud creatures that came alive, she made parts of herself into birds and knew what it felt like to fly, she became fish and knew what it felt like to breathe water. She’d learned to run and to sing, all in the space of a single season, the autumn of the year the Jews were sent away from Rimon.

Then she’d died, violently and quickly.

Nevertheless, during her abbreviated life, bookended by the amulet at one end and her murder at the other, Toba performed two feats never before carried out in all the history of Mazikdom. The first of these was to save the life of the heir of Luz. The second was to create a buchuk who became independent enough to survive Toba’s own death.

No one (save possibly the Peregrine of Rimon) knew precisely how many of the heirs of Luz had been murdered since the death of the Queen, but it had been many. Until Toba saved Barsilay b’Droer in La Cacería’s prison, none had survived more than a few months. This was significant in ways that Toba herself did not understand, because a surviving heir set things in motion that had been stalled since the day that Luz had fallen beneath the sea.

As for the buchuk, Toba did not know how or why she’d made her, if not to die in Toba’s stead. It seemed to be the natural order, for the creation to die before the creator, or at least that was what had been decided when Toba Bet was sent to marry Tsidon the Lymer, while Toba herself went to rescue Barsilay. Toba the Elder had believed she was taking the safer path; Toba the Younger had believed she was on her way to her own end. Instead, Toba Bet had survived, and Toba had perished at the hand of the Courser of Rimon, a gruesome death that had sent her spirit hurtling into the void.

She and Toba Bet had both felt it, the initial pain, followed by the slow extinguishment of her consciousness, leaving nothing but the original Toba’s awareness that she was very much alone in the void—and even this awareness was slowly winking out.

It was a screaming sort of horror, slipping into nonexistence, and Toba fought as it crept up through her mind, thinking, as all Maziks did in those final moments, that if she only willed herself to remain, she could not cease to exist. The edge of the void was terrible, they all told themselves, but it must be better than the void itself. Nothing could be worse than that.

Toba held fast for so long she began to think she had beaten it. Perhaps if she let her will drift from fighting, for one moment, and let her mind shift to more pleasant thoughts, she might know something other than nothingness.

This, of course, was how all Maziks died.

Only what happened to Toba was something different.

As what remained of her began to fade away, she heard the sounds of wings in her ears and thought, There are no birds in the void, I don’t think. And then there were voices, melodious voices, whispering to her, “Little bird, you do not belong here.”

Are you demons? Toba thought, because demons had whispered to her, and the demons she had known had called her not Little bird, but Birdling, which was very close.

The voices said, “No, we are not demons.”

Then Toba felt herself return, and only then realized she had been returning for some time—first her hearing, then her sight, and then her physical body (or at least some reasonable approximation). She felt hands on her arms and there were so many sets of eyes she felt faint from them. She covered her face and cowered, and then the voices, no longer so melodious but now rather ordinary, said, “Open your eyes, Tsifra N’Dar.”

Toba complied, because apparently her name was still her name, even in death. She looked down at herself and saw that she was rather insubstantial, much as the dead were in the dream-world, and knew that she had not returned to life. Instead, she was inside what looked to be a shul, an old stone building with horseshoe-topped arches, much like the shul she’d visited in Rimon. The walls were ornately carved with Hebrew poems, some of which she recognized and others not. Before her were three bearded men, dressed in the manner of rabbis, sitting behind a grand wooden table on a raised dais, while she stood on the floor beneath them.

“Where is this place?” she asked the men, and one said, “You have been brought here, to Aravoth.”

“Aravoth,” she whispered, then added, “Are you not a beit din?”

“We are,” said the rabbi in the middle, who was the tallest and the one who had spoken. His eyes were not like a Mazik’s, nor were they like a human’s; they were simply black all the way across, which was deeply unsettling. Toba thought that these rabbis probably did not truly look like this. This was some trick of perception. If she were indeed in Aravoth—and she had no reason to suspect the rabbis were lying—then these were angels, and she was being called to account. She said, “Am I to be judged?”

“Not by us,” the rabbi-angel said. “The matter at hand is what is to be done with you. You are too much a Mazik to die as a mortal, and too much a mortal to die as a Mazik. So we have discussed, and we leave the choice to you, to tell us where your heart lies. What is your spirit, truly?”

Choose an afterlife, what a decision.

She said, “I can hardly be the first half-Mazik ever to die.”

The rabbi-angel looked quite consternated, a strange expression which did not suit his face. He said, “You are not the first half-Mazik to die. But you are the first to die both violently and awake. The others before you all chose a dreaming death. So we were not made to be involved.”

She said, “I was told the dreaming death was given only to Maziks who died in their sleep, and the rest go to the void.”

The rabbi-angel smiled and said, “They do go someplace different, however—”

“Well, where? Where is it Maziks go?”

“You are speaking quite out of turn, Tsifra N’Dar.”

Toba prickled at this. “Seeing what’s at stake, I believe I am entitled to ask questions.”

The rabbi-angel looked quite affronted and said, “Entitled! To what are you entitled? You are a mortal creature—even Maziks are so. You have lived and you have died, and now all that remains is to decide where your spirit will go. Choose.”

“I would be happy to choose,” Toba said. “But as I have said, you have not told me what I am choosing between.”

The rabbi to the left, who looked somewhat less happy to be having this conversation (that is to say, very unhappy indeed) said, “Perhaps you would prefer us to return you whence we found you?”

“I don’t believe you can,” Toba said. “Isn’t that why I’m here?”

“Your impertinence is astounding,” the first angel said (Toba had, by this point, stopped thinking of them as rabbis because a rabbi would have appreciated her argument). “You will recall that your unwavering belief in your own cleverness is what got you killed in the first place.”

“My sister removing my head is what got me killed,” Toba said. “Don’t make that out to be my fault. And anyway, if you know what I was doing when I was killed—which is to say, saving someone’s life—does that not also tend to sway things in my favor?”

“Your actions on that day had merit,” he said. “They do not entitle you to additional consideration here. You must choose what happens to your soul based on how you feel it within you.”

Refusing to give her the information she needed to make a reasonable decision irked Toba and struck her as terribly unfair. What if Maziks really did go to the void? The mortal choice seemed the more sensible. On the other hand …

“I submit to you that it is unjust for me to be dead in the first place.”

The angel made an expression that was not unlike the one Asmel had made when she’d argued with him back in the alcalá, when she’d rejected his hospitality in favor of a bargain with better terms. He’d been very angry that day. The angels were no less angry with her now. Before the angel could call her absurd and render her unable to speak (which she felt was the logical next step for him), she said, “In the Birchot HaShachar each day we say, ‘Adonai, the soul You have placed within me is pure. You guard it while it is within me; someday it will return to You, and You will restore it to me in a time beyond time. As long as my soul is within me, I will thank You.’ Listen. My soul is either within me, for which I thank Hashem, or else it is with Hashem. But half my soul is on earth with Toba Bet, because she is still alive! How can it be in both places? If I am split this way, does it not violate the sanctity of my soul?”

The angels thought this over, then the second among them—the one Toba thought of as preternaturally crabby—said, “Is it not also said that husband and wife share the same soul, and that when the younger is born, part of the elder’s soul is given to them? Then, is not part of the soul on earth and part with God after one of them dies?”

Toba said, “Did I marry myself? How is that analogous, unless you are claiming that I am my own husband and Toba Bet is my wife?”

The chief angel said, “We reject your argument.”

“You cannot simply reject my argument! You must refute it, which you have not done. This is the law.”

“And who are you to lecture us about the law?”

“And who are you?” she shot back. “You are a being created by Hashem to serve whatever purpose you have been given. I am no different, nor am I inferior in reason. So you must either refute my argument, or else you must accept it, in which case I cannot remain dead.”

A long silence stretched between them. She did think, at that time, that the angels meant to cast her back into the void. But she would not be sorry for making the argument. It was, she believed, her obligation to her very soul.

Finally, the chief angel said, “What would you have us do, then? Bring the other Toba here?”

“That would be murder,” Toba said. “Would it not?” Before the angel could form an answer, she said, “I would be revived. Elijah and Elisha both revived the dead, and as they were only prophets, that must be in your power, as angels.”

The angel said, “If we do as you ask, your soul and the other’s are still part of the same whole, and the problem is unsolved. When one of you dies, we begin this argument again. You ask us to create a paradox. You cannot live forever.” The third angel, the smallest of the three, and with the least quantity of beard, said something in his ear and he nodded. “We will confer among ourselves, Tsifra N’Dar.”

The angels vanished, leaving Toba sitting alone in the shul, and she reached into her mind, looking for her other self. Until the moment of her death, they’d seen through one another’s eyes, and she wondered that she hadn’t had a sense of her counterpart since she’d been brought out of the void. She would have asked the angels how the connection had been severed, but since it did not seem to bolster her argument she decided she had better stay quiet on the matter.

The angels returned only a few moments later, reappearing in their original spots, and again the tallest spoke. “We have a solution,” he said. “We cannot return you to life as you were. But we can give you a new body, a new name, and you will be born as someone else. In this way, your soul will be separated from the soul of your buchuk. You will live another life, and you will die, and at that time you will not speak before us again.”

Toba said, “What will I remember of myself?”

“That we cannot say,” the angel said. “You may remember, or you may not. But because you died protecting another, we will give you this choice, Tsifra N’Dar: Would you go to where you will be safest and no harm will ever come to you, or would you go to where you can do the most good?”

“What does that mean?” Toba insisted. “Where I will do the most good for whom?”

The angel slammed his hand down on the table, making a sound so loud that Toba, for the first time, felt afraid. “Your choice has been laid out for you,” he said. “Make your decision.”

Toba said, “Then I will choose to go where I can do the most good.”

The angels nodded to one another. Then the smallest among them, who had not yet spoken aloud, came forward from behind the table and said, “Your name, from now on, shall be Dagah N’Dar. And there is one more thing, Dagah N’Dar: In payment for this new life, you must never take another.”

And Toba opened her eyes on the day of her birth, and on her tongue was her new name. “Dagah N’Dar,” she said, and felt her new name settle on her like a mantle—the Splendid Fish.

ELENA PERES’S GREATEST desire in all the worlds was for a pocketful of salt, or a spoonful, or even a thimble’s worth. She’d even have settled for a few grains, enough to give a Mazik a good long stomachache.

Alas, she’d used up what little salt she’d had rescuing Barsilay from disaster back in Zayit, and now here he was again, in a Mazik prison. The man seemed to have the worst luck imaginable; she only hoped they could get him out this time before he found himself short any more limbs.

Elena did not give voice to any of these ruminations because she knew her desire for salt would cast her as murderous, and her feelings about Barsilay as glib, but she was neither, really. She was only a woman who had succeeded in staying alive a very long time under some very trying circumstances. One tended not to grow overemotional about impending doom the tenth or twelfth time around. She’d have thought that Maziks, with all their immortality, would be more understanding of the sentiment. But it seemed the Zayiti Maziks she’d thrown in with were unused to having their lives threatened.

Their current predicament—Elena’s and the Maziks’—went something like this: She, Barsilay, Asmel, and the old woman had come to P’ri Hadar together with some hundreds of Zayiti refugees, who had been forced to flee when Tarses had used some sort of demonic fire to burn their city to ash.

While they had been sent to the great city of the east in the hope of safety, Toba and Naftaly had passed into the mystical third realm of Aravoth in order to find the Ziz, that she might help them restore the gate of Luz to the firmament.

This was a great deal of information, even for Elena.

Unfortunately for them, Queen Kasfia of P’ri Hadar had some foreknowledge that Barsilay was the heir of Luz, information they’d believed would not have reached so far, and at the first sight of him she had thrown him in her dungeon. In the aftermath, Elena had been left before Queen Kasfia with Efra b’Vashti, the Savia della Mura of Zayit, who seemed to be the highest-ranking official to have survived the razing of the city. Efra had spoken very fast to Kasfia about the inhospitality of arresting a man who had come seeking aid, and which unwritten Mazik code this violated. She’d listed several. The Queen had been unmoved.

“Get them out of here,” she’d told her guards, referencing Efra and Elena both, as Barsilay was already being dragged away, his real and phantom wrists both chained. Elena had managed to get close enough to him to say, “I have a plan” (untrue, she had none), but he’d replied, “Don’t make her our enemy,” and then he’d been pulled one way down the main corridor and Efra and Elena the other.

And now, the two women were left somewhat dumbfounded, standing outside the palace gates. Elena said, “Did you expect her to do that?”

Efra said, “I did not expect she’d know him as the heir of Luz, no. Disaster upon disaster; we didn’t so much as get a sack of lentils for all our people.”

The only thing that had gone well was that the Queen hadn’t recognized Elena as a mortal, which itself surprised her. She was veiled, but it wasn’t such a good disguise. She wondered if Kasfia in fact had recognized her, but chosen not to call attention to it. “What will she do with him?” she asked.

“Will she execute him?” Efra asked. “I don’t know. It was already a violation of the code of hosts for her to arrest him only for being the heir to a throne she’d like forgotten; I don’t know what she’ll do with him now. What did he say to you?”

“Not to make her our enemy.”

“Too late for that,” Efra said.

“My guess is he’s hoping we’ll find a solution that encourages the Queen to help us restore the gate.” Elena huffed a little. She was exhausted and she’d breathed too much smoke back in Zayit. “I need to think.”

“We need to find a way to feed and house all the Zayitis,” Efra said. “We never even got to put that request in.”

“Isn’t there someone else we could ask? I don’t suppose Maziks have leagues for widows and orphans?”

Efra said, “No, we certainly don’t.” She set her jaw and began to walk down the palace steps. The sun was rising over the city, a vast place carved—or magicked—from beige sandstone. The buildings lacked the color of Zayit, but the contrast between the vivid blue of the sky and the yellow of the buildings was dazzling nevertheless. Flanking the steps were two statues of what Elena knew must be Leviathans, great fish leaping into the air from massive bowls of quicksilver. The statues themselves were either made entirely of silver or plated in the stuff. Floating in the bowls of quicksilver were lotus flowers carved from alabaster. As they passed, Elena could have sworn the blossoms smelled real. From the front of the palace one could look all the way down to the sea, bluer even than the sky.

She decided she would ask Asmel about the statues later—the matter at hand was feeding the Zayitis. There were three avenues to persuade a woman like Kasfia: pity (only she appeared to be without any), threats from someone even more powerful (only she had imprisoned Barsilay, making him her enemy), and of course, the universal lubricant: money (only they had none). The Zayitis were the wealthiest Maziks in existence, but they’d escaped with little more than the clothes on their backs. Perhaps, if they were very lucky, one of them had run away with a purse in their pocket.

“What is your plan?” Elena asked as she followed Efra back through the stone city, past the gated courtyards of the Maziks wealthy enough to live near the palace, all filled with orange trees that were covered with blooms and left the streets smelling like perfume. It was early enough in the day that there were few Maziks about, only a few shades sweeping doorways and the occasional cat watching them from the top of a wall.

“Barsilay will have to wait,” Efra said. “If history is any indication, she’ll try to ransom him to us for some ungodly amount we’ll never be able to pay.” At that, Efra turned off the main street, down a side street, then another. The city was not altogether different from Rimon—the streets, once you got far enough from the palace, were all curved in such a way that you had to navigate by keeping one eye on the palace and the other on the wall, otherwise you’d be lost in five minutes.

“Are we not returning to the grove?” Elena asked, to which Efra replied, “Every luxury in P’ri Hadar came through the gate of Zayit and was sold by a Zayiti merchant. The trade guilds have a significant presence here.”

“Wasn’t it your salt guild that betrayed you to Tarses? You think the guildsmen here won’t know you executed all their friends?”

Efra pursed her lips and said, “I doubt word will have traveled so fast. Anyway, the guilds are not so entirely enmeshed. We’ll begin with the spice guild.”

Only when they arrived in the Zayiti quarter, they discovered the door to the spice guild had been broken and the building was empty. Elena followed Efra inside, watching quietly as she walked the perimeter of the main room, taking in the scuffs on the floor and the dust on the windowsills. “They’ve been arrested,” she said.

“Are you sure they didn’t just flee? Perhaps they got wind of what happened to the salt guild in Zayit and were frightened.”

“And they broke their own door in? No, they were taken, and someone knows why.” She removed her earring and set it into the doorway. “The guilds aren’t the only presence Zayit has in this city. The Queen may have taken the merchants. But she won’t have captured the spies.” She tapped the earring three times.

Barsilay had told Elena that Zayit ran on money and secrets, and their spy network was even more adept than Tarses’s. “Do we wait here?” Elena asked her.

“No,” Efra said, straightening. “They’ll find us.”

WHILE ELENA WISHED most for a handful of salt, what Toba wanted most of all was Elena.

This was the Toba formerly known as Toba Bet, the surviving buchuk of the Toba that had died in Rimon and been returned to life as Dagah N’Dar, and she felt herself as much Elena’s grandchild as the original had been. And as Elena turned her path from the palace of P’ri Hadar, Toba felt herself slipping into memories that had belonged to her other self, of the childhood in which Elena loomed mythically large, as mothers and grandmothers often do.

In the house of Elena Peres, there had been one rule above all others: Toba was never to be left alone. When Elena was at home, Toba was nearby, mimicking her at her chores. And when Elena had to venture out—which was fairly often—she was left with Alasar, to follow along with his students or scratch some lines on a spare piece of paper.

But occasionally, when Toba was very small, Alasar would have his own errands to attend to. On those days, Toba was bundled up and taken with Elena as she went about her day.

She was not to speak on those occasions—Toba had not understood ’til later that this was to conceal the maturity of her mind. She was to wait quietly beside Elena until it was time to go home, and then she was allowed to ask all the questions she wanted.

When she was about seven years old, Alasar had been out visiting some academic friend or other, and Elena had received a message from the rabbi’s wife, asking her to come to the house.

Toba recalled that Elena had very much not wanted to take Toba on this particular errand, and had asked the maid who had delivered the message if the rabbi’s wife could wait ’til after lunch. But the maid had insisted the matter was urgent, so Elena reminded Toba of the rule, covered her with a shawl, and off they went. It was cold that day, Toba remembered, and her eyes had stung in the wind as she’d walked behind her grandmother. Her legs were short and it had seemed like a very long way to the rabbi’s house.

The rabbi’s wife had wanted Elena to write a letter on her behalf. Toba did not know who the letter was for or what it was about, but the rabbi’s wife had insisted the two women have privacy for the transcription. Elena had balked. The rabbi’s wife had insisted again and then offered her some extra payment.

And so Toba had been left in the kitchen with the maid and some treat to keep her quiet. But Toba had not liked the treat and she was not used to being without her grandparents and the maid had been busy with the making of lunch, so Toba set the uneaten sweet down on the table and slipped out of the kitchen.

She was looking for Elena when she found the rabbi’s empty study. The room had a low table like the one her grandfather used, and the walls were lined with bookshelves, and here Toba paused, because these were different books than those she’d seen at home. Alasar translated science and poetry, in the main; these were holy books. Toba wondered if she could read them as easily as the books she was used to, and if they might tell her something interesting she could share with her grandfather later.

Standing on her toes, she reached for a book with an ornate spine set with gilt along the binding, but then hesitated because the book beside it was so old and worn. It looked like lots of people had read that one, so she slipped it off the shelf instead.

She set the book on the low table and opened it.

Inside, on the page to which it opened, there was a chart: seven spheres interlocking. And they had been labeled in a neat penmanship: the first sphere, Vilon, the second, Raqia. Her eyes scanned to the end of the list.

The seventh sphere: Aravoth.

She turned the page, which began with descriptions of each sphere, then flipped ahead because Aravoth had caught a thread in her mind. Had she heard it at home? From Alasar, maybe, or one of his students, the young men who came and murmured over ancient texts, with hands covered in ink and faces pale from hours spent indoors.

She turned to the page about Aravoth and began to read.

There is a dark place there, where one must not ever look, because it is there that Hashem resides, and no one shall ever look upon Him.

Toba began to tremble as her young mind whirled, and she began to imagine what such a place might look like: bright and then dark, filled with terrifying angels with eyes too numerous to count, their wings beating the air like ten million birds, in a din so loud that Toba, in the rabbi’s study, had to put her hands over her ears just from imagining it. She wept a little and then loudly, with great heaving sobs, ’til Elena heard and came running into the room, the rabbi’s wife behind her.

“She ought not to be in here!” the rabbi’s wife said testily, as Elena took the book from Toba and shut it.

“I asked to keep her with me.”

“If she can’t mind you, she should be left at home—” Her eyes widened. “She can’t have been reading that?”

“Of course not,” Elena covered, though not too smoothly. “Why aren’t you in the kitchen, Toba?”

“The wings,” Toba wept.

Elena returned the book to the shelf without a word. “She’s overtired. I’ll take my leave now.”

“But you haven’t finished writing the letter,” the rabbi’s wife complained.

“Another time,” Elena said, taking Toba by the wrist and pulling her through the door and all the way home.

“You shouldn’t read books in other people’s houses,” Elena said. “You know better.”

But Toba was too upset to reply or to complain or to ask about what she’d read, because in her mind she could still see all those eyes, all those wings, and it seemed to her to be the most frightening thing she could imagine.

She’d forgotten that book long before the day when Toba put her foot through the gate of Luz and stepped into Aravoth. In her hands was the book that held the gate, Naftaly had already passed through ahead of her, and she expected him to be the first thing she saw.

Instead, there was nothing in her vision but eyes, and nothing in her hearing but the sound of wings loud as thunder, or cannon fire, and she dropped to her knees and wept.

TSIFRA N’DAR, THE COURSER of Mazik Rimon and Toba’s sister, wished most of all for some clarity of purpose. She had been the left hand of the new age, a tool to manipulate the Mirror, and a vengeful angel. But now she would have to become an entirely different creature: a queen.

She’d killed the former Queen of Sefarad, and now Tsifra wore her face. She’d spent days among her advisors in the city of Mansanar, to which she’d traveled after the fall of Zayit. And she’d learned more about the woman whose place she’d had stolen: She was bellicose without dirtying her own hands with the stain of battle; she was holy without claiming herself an icon; she was an administrator, a maker of law, and a leader of soldiers and pious men and farmers alike.

Tsifra was uncertain how to carry on in this woman’s vein. She would need to oversee battles—which the former queen would not have done—and find some way to explain the obvious shifts in her character.

She had no model for any sort of rule besides Tarses and his twisted promises, his unwavering belief in his own personal importance. She’d wondered, in her younger days, whether he believed his own rhetoric: He’d called monarchy abomination but then put Relam on the throne of Rimon; he’d executed men for contact with mortals while conceiving two half-mortal children. What she’d come to realize was that Tarses was a man of faith, and the central figure of this faith was himself. Whatever else he might have done, or wherever else he’d seemed to alter his course, he believed, truly, that he was the savior of the Maziks.

The only way forward Tsifra could see was by casting herself in a similar mold, a mirror of her father, but within the boundaries of the woman whose name she’d claimed. She settled into her persona, felt around the edges, and wondered what she might do if, like Tarses, she were a savior—no, not a savior. She was still too much herself, the Courser of Rimon. And the Courser of Rimon was a messenger.

On the night before she was to leave for Barcino she went to her advisors and said, “The Angel of Zayit has visited me this night and gifted me with a vision. She has shown me the heretics of Zayit turned to ash, and bade me continue on to Anab, where she set me a

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...