- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

After the horrifying explosion that claimed one of their own, the Diviners find themselves wanted by the US government, and on the brink of war with the King of Crows.

While Memphis and Isaiah run for their lives from the mysterious Shadow Men, Isaiah receives a startling vision of a girl, Sarah Beth Olson, who could shift the balance in their struggle for peace. Sarah Beth says she knows how to stop the King of Crows—but, she will need the Diviners' help to do it.

Elsewhere, Jericho has returned after his escape from Jake Marlowe's estate, where he has learned the shocking truth behind the King of Crow's plans. Now, the Diviners must travel to Bountiful, Nebraska, in hopes of joining forces with Sarah Beth and to stop the King of Crows and his army of the dead forever.

But as rumors of towns becoming ghost towns and the dead developing unprecedented powers begin to surface, all hope seems to be lost.

In this sweeping finale, The Diviners will be forced to confront their greatest fears and learn to rely on one another if they hope to save the nation, and world from catastrophe...

Release date: February 4, 2020

Publisher: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

Print pages: 560

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

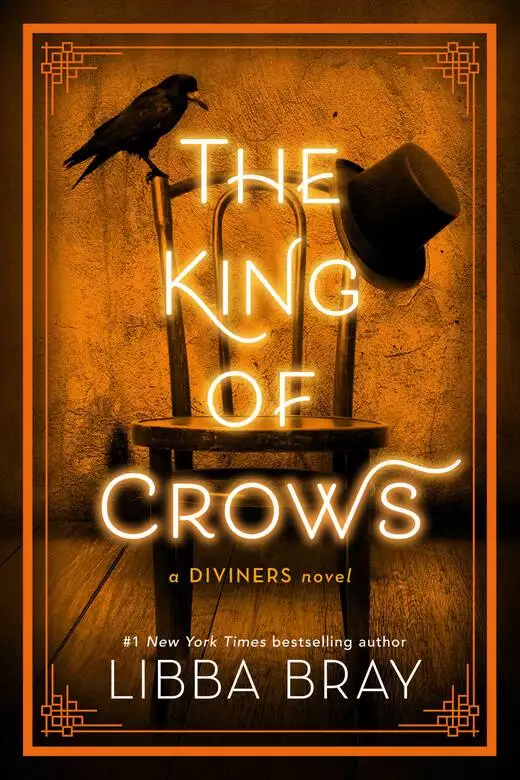

The King of Crows

Libba Bray

On the last day that the town of Beckettsville would ever know, the weather was so fine you could see all the way to the soft blue skin of the horizon. The land in this part of the country was beautiful. Tall wheat tickled the spring air. Fat maples offered summertime shade. There was a fine-looking Main Street boasting a post office, a hardware store, a filling station with two gasoline pumps out front, a grocery, a pharmacy, a small hotel with a downstairs cafe that served warm apple pie, and a barbershop whose revolving red-white-and-blue pole thrilled the children, a daily magic trick.

A round clock mounted to the front of City Hall’s domed tower showed the passage of time, which, in Beckettsville, seemed to move slower than in other places. The people worked hard and tried to be good neighbors. They sang in church choirs and attended Rotary and Elks Club meetings. They played bridge on Friday nights. Held picnics near the bandstand under the July sun. Canned summer peaches for the long winter. Got excited by the arrival of a new Philco radio, electric icebox, or automobile, everybody crowding ’round to see progress unloaded from the back of a truck by grunting, sweaty men. The people lived in neat rows of neat houses with indoor plumbing and electric lights, attended one of the town’s four churches (Methodist, Presbyterian, Baptist, and Congregationalist), sent their dead to the Perkins & Son Funeral Parlor over on Poplar Street for embalming, and buried those same dead in the cemetery up on the hill at the edge of town, far from the bustle of Main Street.

As the clock counted down to the horrors awaiting Beckettsville, population four hundred five souls, Pastor Jacobs stepped out of First Methodist Church thinking of that apple pie over at the Blue Moon Cafe—so delicious the way Enola Gaylord served it, with a dollop of cream, and it really was a shame he would not get to enjoy Beckettsville’s favorite pie today or any day thereafter. The pastor nodded and said “Afternoon” to sweet Charlie Banks, who swept the sidewalk free of spring blossoms in front of McNeill’s Hardware. Charlie mooned over the approach of pretty schoolteacher Cora Nettles. As Cora marched past him (her own thoughts occupied by a silly but maddening argument she’d had with her mother over the new pink hat Cora now wore—it most certainly was not “unbecoming of a serious woman”!), Charlie sighed, thinking that tomorrow, or perhaps the day after, he would finally summon the courage to ask her to the picture show over in Fairview and that she might answer sweetly, Why, Charlie Banks, I would love to! so that the world of his heart, which Charlie held so tightly in his fist, would open into the bright, fresh bloom of his long-desired future.

Down that same Main Street, Mikey Piccolo, age ten and with his mind firmly fixed on baseball, tossed the day’s Beckettsville Gazette over picket fences from a satchel stretched around his neck as if he were Waite Hoyt. He could hear the imaginary crowd roaring inside his head as he narrowly missed Ida Olsen, who played with her rag dolls under the leafy canopy of a sycamore tree at Number Ten Main Street. She stuck her tongue out at the back of Mikey’s head but quickly moved to the other side of the giant tree to continue her game, out of sight of the Widow Winters, who had just come onto her front porch. Ida did not care to be pulled into a long conversation about boring things from the past—cotillions, which were dances, apparently, and Times When Neighbors Acted More Neighborly. It was never worth the butterscotch candies the old lady offered from the pocket of her apron, and so Ida kept well hidden. From her perch on the porch, Mrs. Euline Winters soothed herself with the gentle seesawing creak of her rocking chair and a lapful of knitting yarn as she watched the citizenry going about their busy business in the noonday sun. (What a glorious afternoon it is! So warm and fragrant!) Her crepe myrtle had blossomed, and the flowers, planted in happier times, reminded Euline of her husband, Wilbur, dead and gone these eight years, and did those people out there, her neighbors, know how lonely she was, sitting alone at her supper table each night, listening to the mocking tick of Wilbur’s grandfather clock, with no one to ask, And how was your day, my dear?

There were other citizens out and about on this beautiful day. A mailman and the Rotary Club president. A dotting of mothers gathered around the butcher’s counter, giving the day’s order while scolding their unruly children. The town crank, who complained under his breath about the unruly children and spat his tobacco into the bushes. The young people restless to grow up and leave Beckettsville or restless to stay right there and fall in love, sometimes feeling both in the same moment, as young people do.

This town held many stories. In a few minutes, none of them would matter.

For weeks, some of the town’s ghosts had tried to warn the people of Beckettsville. Newly awakened from rest, aware of the terrors to come, the ghosts swept picture frames from mantels. They spilled the milk. They caused the electric lights to flicker until the fragile bulbs exploded with a pop. They appeared briefly at windows and in mirrors, their mouths opening in silent screams. The ghosts moaned into the night, but who could hear such alarms over the noise of the radios in every house? The dead of Beckettsville had done what they could, but the people refused to see. Anyway, it was much too late now.

It was Johnny Barton, age twelve, who noticed first. Johnny was upstairs in his bedroom, pretending to be sick again and tending to his model planes, far from the other boys at school who bullied him so mercilessly. (“They’re just teasing,” his mother would say, as if that was supposed to be a comfort. “Hit ’em back. Be a man,” his father would say, which only made Johnny feel bullied twice.) Johnny liked birds and flying things in general, things that suggested you could soar up and away anytime you liked, and so he was zooming his balsa-wood flier past the window when he took note of the curious dark clouds gathering now along that promising horizon. Plenty of storms blew in across the land in spring. But this was something different. These clouds pulled together like filings drawn to a magnet, massing quickly into a living wall. Blue lightning sliced through that thickening dark, as if something terrible was trying to birth itself.

Still gripping his plane, Johnny Barton raced down the stairs. He pushed through the white picket gate of his parents’ foursquare and out into the street, not caring about the Model T that beeped its horn angrily as it swerved around him. “Watch out!” the driver, Mr. Tilsen, barked. But that’s what Johnny was doing, watching out. Every night, he read with relish stories of the Great War. He’d read that, on the battlefields of Flanders and the Somme, fat clouds of smoke and dust announced the arrival of the Germans’ monstrous war machines. That’s what this strange formation reminded him of now—an invading army.

Others were coming to look at the storm blowing in out of nowhere. Wind whipped the leaves of the maples. A sudden gust blew Cora’s fashionable spring hat clean off her head and sent it rolling down the street, where Charlie picked it up, happy to touch something that belonged to her at last. Reluctantly, he handed it back, his fingers grazing hers for one charged moment. Then he, too, turned his head in the direction of those foreboding clouds.

Cora snugged on her cloche and held it in place with the palm of her hand. “Mercy! I hope it’s not a twister!”

“Never seen a twister look that way,” Charlie answered, his mind more on Cora than the storm.

“Maybe it’s the Huns!” Johnny said and scraped his plane through the air. His skin prickled, though he didn’t know why.

“Looks like a big old ball of dust,” the Rotary Club president said in wonder.

“Should we ring the church bell and get to the storm cellars?” Pastor Jacobs asked.

“Let’s wait and see,” the president said. He did not like making decisions until he knew what the popular vote would be.

The mothers had left the butcher shop. Their children stopped squabbling and moved close to their mothers’ sides. The town crank slowed his chew. The restless young people greeted the arrival of the storm with excitement—finally, something! Euline Winters’s rocking chair stilled; her knitting needles lay in her lap. “I saw a dust storm like that once when I was a girl. When it was over, little Polly Johansen was missing. They never found her,” Euline called, though no one listened.

The clouds had spread out. The citizens of Beckettsville could no longer see the horizon. The high-pitched whine of insects filled the charged air. The birds shrieked and flew away from Beckettsville with a startling suddenness. Ida Olsen left her hiding place and came out of her yard, dragging her dolly behind her. Even though her mother had told her that pointing was rude, she jabbed a finger toward the spot of road still visible. “What’s that?” Ida asked.

A lone man emerged from those billowing clouds. He was imposing in stature, with a stovepipe hat atop hair that was kept longer than was the fashion in this part of the country, and an old-fashioned undertaker’s coat made of blue-black feathers that fluttered in the gusty wind. The people of this small town were unaccustomed to strangers—there wasn’t even a train depot here—and this man was strange, indeed. He walked with a deliberate stride, and that made the people wonder if he might be important. A beautiful crow perched sentinel-straight on the man’s left shoulder, cawing like a town crier. To Johnny Barton, it seemed the crow wanted to fly away from its master but stayed as if an invisible chain held it firmly in place.

The man trailing the storm reached the citizens at last. His skin was the patchy, peeling gray of a rotting shroud, and Cora Nettles tried to hide her distaste. She hoped it wasn’t catching, some foreign disease. The man tipped his tall hat with easy formality. “Good afternoon.”

The president of the Rotary Club stepped forward. “Afternoon. Walter Kurtz, president of the Beckettsville Rotary Club. And who might you be?”

“I might be many things. But you may call me the King of Crows.”

The citizens chuckled lightly at this. The Rotary Club president heard and grinned. “Well, we don’t get much royalty in these parts,” he said, playing to his bemused neighbors, happy to know the popular vote at last. “You on your way through somewheres?”

“In a manner of speaking.”

“We don’t get many strangers here,” Cora Nettles explained.

“I am not a stranger,” the man replied, and it left Cora unsettled. She could not place his face.

“You might want to take shelter, sir,” Pastor Jacobs said. “There’s a storm right behind you.”

The King of Crows glanced over his shoulder at the mass of dark clouds hovering on the edge of town, and turned back, untroubled. “Indeed there is.” With eyes black and lifeless as a doll’s, he surveyed the little town. He inhaled deeply, as if he were not merely taking in air but breathing in the full measure of something unknown. “What a fine claim you have here.”

The Rotary Club president beamed. “Why, there’s no town finer. You can have your Chicago, your San Francisco and Kansas City. Right here in Beckettsville—this is the good life!”

“We’ve even got a hotel,” Charlie Banks said, and he hoped Cora thought he was clever to mention this.

The corners of the stranger’s mouth twitched but did not extend into a smile. “My. And how many souls live here?”

“Four hundred five. Almost six, seeing as Maisy Lipscomb is due any day now,” Charlie answered.

“And how many dead have you?”

“I… beg pardon?” Charlie said.

“No matter.” The King of Crows smiled at last, though there was no warmth in it. “You’ve sold me. We’ll take it.”

“Take what?” the Rotary Club president said.

“Your town, of course. We are hungry.”

The citizens laughed again, uneasily this time.

“The pie at the cafe is delicious,” Pastor Jacobs said, still trying to make everything seem perfectly normal, though his heart said otherwise.

The Rotary Club president straightened his spine. “Beckettsville is not for sale.”

“Who said anything about a sale?” the King of Crows answered. His gray teeth were as sharp and pointed as a shark’s.

“I think you’d best move along now,” the town crank chimed in. “We don’t go for funny business here in Beckettsville.”

“Who is we?” Johnny Barton hadn’t meant to ask his question aloud, but now he had the attention of the King of Crows, whose stare fell on Johnny, making him squirm.

“What was that, my good man?” he asked.

Johnny had known lots of bullies, and this man struck him as the worst kind of bully. The kind who pretended to be on your side until he led you behind the school for the beating of your life.

“You said we. Who is we?” Johnny mumbled. He blinked at the crow on the man’s shoulder, because he could swear it now had a woman’s face. The bird spoke with a woman’s desperate whisper. “Run. Please, please run.”

“Be still.” The King of Crows pulled his hand across the woman’s mouth and it became a beak once more, cawing into the wind. The King of Crows’s face lit up with a cruel joy. “How smart you are, young man! Who, indeed? How rude of me not to introduce my retinue.”

With that, he raised his arms and flexed his long fingers toward the sky as if he would pull it to him. Blue lightning crackled along his dirty fingernails. “Come, my army. The time is now.”

A foul smell wafted toward the town: factory smoke and bad meat and stagnant pond water and battlefield dead left untended. Pastor Jacobs put a handkerchief to his nose. Ida Olsen gagged. The crow strained forward with frantic screaming. From inside the dark clouds, a swarm of flies burst forth, as if the town of Beckettsville were a corpse rotting in the waning sun. On that horizon that had seemed so fine moments earlier, the churning clouds parted like the curtain before the start of a picture show, letting out what waited inside.

And though it was far too late for him, or for anyone else in Beckettsville, Johnny Barton heeded the crow’s advice; he turned and ran from the horrors at his back.

New York City

The musty tunnel underneath the Museum of American Folklore, Superstition, and the Occult was as dark as the night’s shadow, and Isaiah Campbell was afraid. His older brother, Memphis, lifted their lantern. Its light barely cut into the gloom ahead. The air down here was close, like being buried alive. Isaiah’s lungs grew tighter with each breath. He wanted out. Up. Aboveground. Memphis was nervous, too. Isaiah could tell by the way his brother kept looking back and then forward again, like he wasn’t sure about what to do. Even big Bill Johnson, who didn’t seem afraid of anything, moved cautiously, one hand curled into a fist.

“What if this doesn’t go nowhere?” Isaiah asked. He had no idea how long they’d been down here. Felt like days.

“Doesn’t go anywhere,” Memphis corrected, more of a mumble, though, and Isaiah didn’t even have it in him to be properly annoyed by his brother’s habit of fixing his words, which, to Isaiah’s mind, didn’t need fixing.

“Don’t like it down here.” Isaiah glanced over his shoulder. The way back was just as dark as the way ahead. “I’m tired.”

“It’s a’right, Little Man. Plenty’a slaves got to freedom out this passage. We gonna be fine,” Bill said in his deep voice. “Ain’t got much choice, anyhow. Not with them Shadow Men after us. Just watch your step.”

Isaiah kept his eyes trained on the uneven ground announcing itself in Memphis’s lantern light and wondered if the Shadow Men had shown up at Aunt Octavia’s house looking for them. The idea that those men might’ve hurt his auntie made Isaiah’s heart beat even harder in his chest. Maybe the Shadow Men had gone straight to the museum, to Will Fitzgerald and Sister Walker. Maybe the Shadow Men had found the secret door under the carpet in the collections room and were down here even now, following quietly, guns drawn.

Isaiah swallowed hard. Sweat itched along his hairline and trickled down between his narrow shoulder blades under his shirt, which was getting filthy.

“How much longer?” he asked for the fourth time. He was thirsty. His feet hurt.

Memphis’s lantern illuminated another seemingly endless curve of tunnel. “Maybe we should turn back.”

Bill rubbed the sweat from his chin. “Not with those men after us. Trust me, you don’t want them to catch ya. Around that curve could be a way out.”

“Or another mile of darkness. Or a cave-in. Or a ladder leading up to a freedom house that hasn’t been that since before the Civil War,” Memphis whispered urgently. “A house that’s home to some white family now who might not welcome us.”

“Rather take my chances goin’ fo’ward.”

They pressed on. Around the bend, their tunnel branched into two. A smell like rotten eggs filled the air and Memphis tried not to gag.

Bill coughed. “Look like we just met up with the sewers.”

Isaiah pinched his nose shut with his fingers. “Which way should we go?”

“I don’t know,” Memphis said, and that scared Isaiah, because if there was anything his brother was good at, it was acting like he knew everything. “Bill?”

Bill held up a finger, feeling for air. He shook his head. “Ain’t no way to know.” He took out a nickel, tossed it, and slapped it down on his arm. “Heads we go left; tails, right.” Memphis nodded. Bill took his hand away. “Tails,” he said, and they entered the tunnel to their right.

“Maybe those Shadow Men left Harlem and went back to wherever they come from,” Memphis said. Water swished over their shoes and trickled down the narrow brick walls. It stank.

“Doubt it,” Bill panted. “They never stop. I know ’em.”

“I didn’t even get to tell Theta good-bye. What if they went to her apartment to find me? What if… what if they hurt her?”

“Only thing we can do is keep going,” Bill said. “Soon as we get somewhere safe, you can put in a call to her, and to your auntie.”

Memphis snorted. “Somewhere safe. Let me know where that is.”

Isaiah chanced another look over his shoulder. Tiny motes of light fluttered in the vast dark. Isaiah blinked, wiped at his eyes. The muscles from his neck to his fingers twitched. Suddenly, his feet wouldn’t move. Isaiah felt as if a giant were squeezing him between its palms. The spots of light came faster, and then Isaiah knew.

“Memphis…” was all Isaiah managed before his eyes rolled back and he was falling deeply into space as the vision roared up inside him, fast as a freight train.

Isaiah stood on a ribbon of dirt road leading toward a flat horizon. To his left, a slumped scarecrow guarded over a field of failing corn. To his right sat a farmhouse with a sagging front porch. He saw a weathered red barn. An enormous oak whose tire swing hung lax, as if it hadn’t been touched in a good while. Isaiah had seen this place once before in a vision, and he had been afraid of it, and of the girl who lived here.

He heard his name being called like a voice punching through miles of fog. “I, I, I, IsaiAH!” And then, close by his ear: “Isaiah.”

Isaiah whirled around. She was right there. The same girl as before. A peach satin ribbon clung to a few strands of her pale ringlets. Her eyes were such a light blue-gray they were nearly silver.

Who are you? he thought.

“I’m a seer, a Diviner, like you.”

She’d heard his thoughts?

The girl curled in on herself like she’d just stepped into a bracing wind. “Something awful has happened, Isaiah, just now. Like a fire snuffed out, and it’s so, so cold. Can you feel it?”

Isaiah couldn’t, and that made him jealous of this strange girl. He was fixated on the horizon, where an angry mouth of dark storm clouds gobbled up the blue sky. The clouds cracked like eggshells, letting out a high, sharp whine, a sound so full of pain and fear and need that Isaiah wanted to run away from it. What is that?

“The King of Crows and his dead,” the girl answered as if Isaiah had spoken. “He’s come, like he promised he would. He’s come and we’re in terrible danger.”

Wind snapped the corn on its stalks. Birds darted out from the roiling, dark sea overhead. Their cawing mixed with the gunfire bursts of screaming. The noise stole the breath from Isaiah’s lungs. So much hatred lived inside that sky. He could feel the threat trying to gnaw its way out into their world.

The girl reached for Isaiah’s hand. Her hands were small and delicate, like a doll’s. “He tells lies, so many lies, Isaiah. He’s been lying to me this whole time, pretending to be my friend. But I had a vision. A lady named Miriam told me the truth. She told me what he did to Conor Flynn. He wants all of us, Isaiah. He wants the Diviners.”

Why?

“Because we’re the only ones who can stop him.” The girl kept her unearthly eyes on the unholy sky. “I know how to stop the King of Crows, Isaiah.”

Where are we? Isaiah asked. He didn’t know why he couldn’t speak here.

“Bountiful, Nebraska. That’s where I live.”

Isaiah saw a mailbox bearing the name “Olson” and the number one forty-four. That number came up a lot. He remembered Evie saying it was the number of her brother’s unit during the war. But her brother and his whole unit had died, and it had something to do with Will and Sister Walker and Project Buffalo and Diviners.

“Where are you?” she asked.

In the tunnel under the old museum. But we’re lost. There’s people after us.

“I’m afraid, Isaiah,” the girl said. “We’re not safe. None of us are. You’ve got one another, but I’m all alone. I can’t fight him and his army by myself. None of us can. We need each other.”

The last time Isaiah had seen this vision, his mama had been here, telling him to get out quick. She had fussed at this girl, told her to hush up. He looked for his mother now but did not see her.

“Please. Come to Bountiful,” the girl pleaded.

The Shadow Men are after us. We’re running from them.

“They don’t know about me. They forgot me. Come here. You’ll be safe. They won’t find you. We must stop the King of Crows before it’s too late!”

Wait! What’s your name? Isaiah thought.

“Sarah Beth,” the girl yelled. The dust billowed behind her pale form. “Sarah Beth Olson. Get to Bountiful, Isaiah! Before it’s too late!”

First we gotta get out of this tunnel. Say, can you see a way out?

“You’re in a tunnel under a museum, you said?”

Yes! In New York City. Manhattan.

The girl shut her eyes. In a minute, she opened them wide. “Isaiah. You’ve got to get out of there right now, you hear? Something’s coming. Go back. Take the other tunnel. Oh, Isaiah, you must hurry. Get out now and come to Bountiful before—”

Isaiah came out of his vision, dizzy and disoriented. Memphis’s worried face was the first thing he saw, hovering above his own. Isaiah sat up too quickly and caught his brother in the nose.

“Ow.”

Bill steadied Isaiah’s face in his strong hands. “You all right, Little Man?”

“Y-yes, sir.” He tasted blood. He’d bit his tongue. And he was sitting in the fetid water.

Bill helped Isaiah to his feet. “You had a vision?”

Isaiah nodded. His head ached. The sewer smell was making him nauseated.

“What’d you see?” Memphis asked.

“She said… she said to go back. Take the other tunnel,” Isaiah said, panicked.

“Who said? Isaiah, you’re not making sense,” Memphis said.

“Hush. Hush now.” Bill held up a hand. “You hear something?”

The boys listened for something under the constant drip of water. Memphis nodded.

“The Shadow Men?” Isaiah whispered. “She said… she said…” The tunnel ahead began to fill with flickering light and deep, guttural growls.

“Not Shadow Men,” Memphis said ominously.

The sound was getting closer.

“Back up,” Memphis said.

“The hell with that. Run!” Bill said.

Memphis grabbed Isaiah’s hand, and they raced back the way they’d come.

“This way!” Memphis said, ducking into the other tunnel, picking up speed as they spied the daylight ahead.

Bennington Apartments

Upper West Side

According to the clock on the bedside table, it was nine fifteen in the morning—an ungodly hour to flapper Evie O’Neill, who never got up before noon if she could help it. She’d been having a nightmare, but she couldn’t remember a thing about it now. Evie stifled an exhausted yawn and looked over at her friend, Theta Knight, who snored lightly. Her sleep mask was slightly askew. Evie nudged Theta twice before giving her a solid shove. Theta startled awake, hands patting at the air until they landed on the sleep mask, which she slid up onto her forehead. She blinked at Evie, then at the clock. “What’s the big idea, Evil?”

“Darling Theta, did anyone ever tell you that you sleep with your mouth open?” Evie impersonated a dead-to-the-world, snoring Theta. “I just didn’t want you to choke.”

With a groan, Theta pushed herself to a sitting position. “That’s called breathing.”

“It’s very loud breathing.” Evie snuggled up next to Theta. For a moment, she remembered all the times she’d done the same with her best friend, Mabel. An awful ache ballooned in Evie’s throat. She refused to start the day with tears. “Theta, did you mean what you said last night?”

Theta arched an eyebrow. “I dunno. What’d I say last night?”

“That you’d help me find Sam.”

“Yeah, I meant it, kid.”

“You’re the berries,” Evie said and kissed Theta’s cheek.

Theta wiped at the spot. “You probably just got a mouthful of cold cream, y’know.”

“Then my lips will be very soft. I want to try his hat again.”

“Evil. You’ve read that hat three times now,” Theta said gently.

“Maybe there’s something I missed! I could sense how afraid he was, Theta. You know Sam—he’s never afraid. I saw those Shadow Men doing something to him, and then I could feel Sam’s body getting cold and slow and numb.”

Theta brought her knees up to her chest and wrapped her arms around them. “You don’t suppose he’s…?”

“No! He is pos-i-tutely not dead!” Evie insisted. She couldn’t bear the thought of it. There’d been too much loss already. “Besides, if anybody is going to have the pleasure of murdering Sam Lloyd, it ought to be me.”

Theta chuckled and shook her head. “You two. I don’t know whether to hope you get married or hope you never do.”

“I only want to know that he’s okay,” Evie said, tearing up at last.

“I know, kid. Here,” Theta said, reaching for Sam’s hat from the bedside table. “You might as well get started. I’ll have the aspirin ready for after. Just don’t do a number on yourself.”

Evie sat with Sam’s hat in her lap. The old Greek fisherman’s cap had belonged to him for a long time. With renewed purpose, Evie pressed it between her palms, receiving small glimpses of Sam’s past. These memories played across her mind like brief scenes in a motion picture, but all jumbled up: Sam talking to a redheaded lady who was laying out a spread of tarot cards. Sam lifting valuables from unsuspecting rubes on Forty-second Street. The day she and Sam had met, when he’d kissed her and stolen twenty dollars from her pocket. That one made her smile just a bit. There was even a hint of the countless girls he’d charmed into his arms, and it tempted Evie to unlock even more of those memories. Last, she wandered across a moment of the two of them sharing a perfect kiss. And then that gave way to the Shadow Men dragging Sam toward the brown sedan, his body growing cold. But then the hat fell to the sidewalk, and that’s where Sam’s history with it stopped. If she wanted a deeper read, she was going to need help.

Evie came out of her trance and looked up at Theta with wide eyes. “Theta, darling Theta.”

“Uh-oh. I know that tone.”

“Please? I only need a boost.”

“My power’s pretty unpredictable, Evil. What if I accidentally set you on fire?”

“Then I’m glad I’m wearing your pajamas and not my own.”

“There’s something not right about you, Evil,” Theta clucked. “Now, listen: If this goes badly, don’t you dare come back and haunt me.”

“Your protest is noted.”

“Uh, how do we do this? Do I touch you? The hat? Both?”

“Both, I think.” Evie glanced at Theta’s fingers and thought about them heating up suddenly. “On second thought, the hat.”

“Here goes nothin’,” Theta said and took hold of the brim with a delicate touch.

Evie shut her eyes and concentrated. A tiny sliver of electricity worked its way up her arm. It tickled like ants, an unpleasant sensation, and Evie tried to breathe through the worry about what might happen if her power and Theta’s didn’t get along. She hoped that Theta couldn’t sense that worry. In a few seconds, the prickling became a surge of energy, as if someone had plugged Evie in to the same electrical socket as Theta, and now their combined wattage was glowing brighter. She could feel Theta’s strong heartbeat like her own. With her friend at

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...