- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

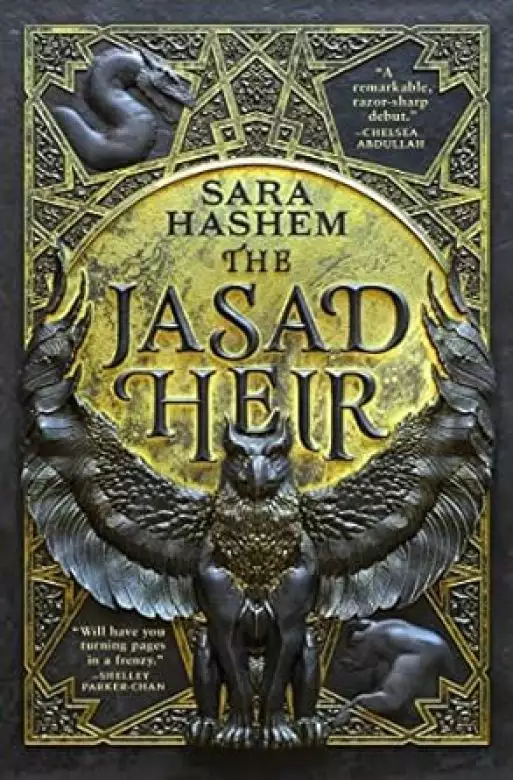

In a world of forbidden magic and cunning royals, a fugitive queen bargains with her kingdom's greatest enemy and is soon embroiled in a deadly game that could resurrect her scorched kingdom, or leave it in ashes forever. A stunning enemies-to-lovers fantasy debut, perfect for fans of Fourth Wing and The Jasmine Throne.

At ten years old, the Heir of Jasad flees a massacre that takes her entire family.

At fifteen, she buries her first body.

At twenty, the clock is ticking on Sylvia's third attempt at home. Nizahl's armies have laid waste to Jasad and banned magic across the four remaining kingdoms. Fortunately, Sylvia's magic is as good at playing dead as she is.

When the Nizahl Heir tracks a group of Jasadis to Sylvia's village, the quiet life she's crafted unravels. Calculating and cold, Arin's tactical brilliance is surpassed only by his hatred for magic. When a mistake exposes Sylvia's magic, Arin offers her an escape: compete as Nizahl's Champion in the Alcalah tournament and win immunity from persecution. In exchange, Arin will use her as bait to draw out the Jasadis he's hunting.

To win the deadly Alcalah, Sylvia must work with Arin to free her trapped magic, all while staying a step ahead of his efforts to uncover her identity. But as the two grow closer, Sylvia realizes winning her freedom as Nizahl's Champion means destroying any chance of reuniting Jasad under her banner. The scorched kingdom is rising again, and Sylvia will have to choose between the life she's earned and the one she left behind.

Release date: July 18, 2023

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Jasad Heir

Sara Hashem

I tromped through Hirun River’s mossy banks, squinting for movement. The grime, the late hours—I had expected those. Every apprentice in the village dealt with them. I just hadn’t expected the frogs.

“Say your farewells, you pointless pests,” I called. The frogs had developed a defensive strategy they put into action any time I came close. First, the watch guard belched an alarm. The others would fling themselves into the river. Finally, the brave watch guard hopped for his life. An effort as admirable as it was futile.

Dirt was caked deep beneath my fingernails. Moonlight filtered through a canopy of skeletal trees, and for a moment, my hand looked like a different one. A hand much more manicured, a little weaker. Niphran’s hands. Hands that could wield an axe alongside the burliest woodcutter, weave a storm of curls into delicate braids, drive spears into the maws of monsters. For the first few years of my life, before grief over my father’s assassination spread through Niphran like rot, before her sanity collapsed on itself, there wasn’t anything my mother’s hands could not do.

Oh, if she could see me now. Covered in filth and outwitted by croaking river roaches.

Hirun exhaled its opaque mist, breathing life into the winter bones of Essam Woods. I cleaned my hands in the river and firmly cast aside thoughts of the dead.

A frenzied croak sounded behind a tree root. I darted forward, scooping up the kicking watch guard. Ah, but it was never the brave who escaped. I brought him close to my face. “Your friends are chasing crickets, and you’re here. Were they worth it?”

I dropped the limp frog into the bucket and sighed. Ten more to go, which meant another round of running in circles and hoping mud wouldn’t spill through the hole in my right boot. The fact that Rory was a renowned chemist didn’t impress me, nor did this coveted apprenticeship. What kept me from tossing the bucket and going to Raya’s keep, where a warm meal and a comfortable bed awaited me, was a debt of convenience.

Rory didn’t ask questions. When I appeared on his doorstep five years ago, drenched in blood and shaking, Rory had tended to my wounds and taken me to Raya’s. He rescued a fifteen-year-old orphan with no history or background from a life of vagrancy.

The sudden snap of a branch drew my muscles tight. I reached into my pocket and wrapped my fingers around the hilt of my dagger. Given the Nizahl soldiers’ predilection for randomly searching us, I usually carried my blade strapped in my boot, but I’d used it to cut my foot out of a family of tangled ferns and left it in my pocket.

A quick scan of the shivering branches revealed nothing. I tried not to let my eyes linger in the empty pockets of black between the trees. I had seen too much horror manifest out of the dark to ever trust its stillness.

My gaze moved to the place it dreaded most—the row of trees behind me, each scored with identical, chillingly precise black marks. The symbol of a raven spreading its wings had been carved into the trees circling Mahair’s border. In the muck of the woods, these ravens remained pristine. Crossing the raven-marked trees without permission was an offense punishable by imprisonment or worse. In the lower villages, where the kingdom’s leaders were already primed to turn a blind eye to the liberties taken by Nizahl soldiers, worse was usually just the beginning.

I tucked my dagger into my pocket and walked right to the edge of the perimeter. I traced one raven’s outstretched wing with my thumbnail. I would have traded all the frogs in my bucket to be brave enough to scrape my nails over the symbol, to gouge it off. Maybe that same burst of bravery would see my dagger cutting a line in the bark, disfiguring the symbols of Nizahl’s power. It wasn’t walls or swords keeping us penned in like animals, but a simple carving. Another kingdom’s power billowing over us like poisoned air, controlling everything it touched.

I glanced at the watch guard in my bucket and lowered my hand. Bravery wasn’t worth the cost. Or the splinters.

A thick layer of frost coated the road leading back to Mahair. I pulled my hood nearly to my nose as soon as I crossed the wall separating Mahair from Essam Woods. I veered into an alley, winding my way to Rory’s shop instead of risking the exposed—and regularly patrolled—main road. Darkness cloaked me as soon as I stepped into the alley. I placed a stabilizing hand on the wall and let the pungent odor of manure guide my feet forward. A cat hissed from beneath a stack of crates, hunching protectively over the half-eaten carcass of a rat.

“I already had supper, but thank you for the offer,” I whispered, leaping out of reach of her claws.

Twenty minutes later, I clunked the full bucket at Rory’s feet. “I demand a renegotiation of my wages.”

Rory didn’t look up from his list. “Demand away. I’ll be over there.”

He disappeared into the back room. I scowled, contemplating following him past the curtain and maiming him with frog corpses. The smell of mud and mildew had permanently seeped into my skin. The least he could do was pay extra for the soap I needed to mask it.

I arranged the poultices, sealing each jar carefully before placing it inside the basket. One of the rare times I’d found myself on the wrong side of Rory’s temper was after I had forgotten to seal the ointments before sending them off with Yuli’s boy. I learned as much about the spread of disease that day as I did about Rory’s staunch ethics.

Rory returned. “Off with you already. Get some sleep. I do not want the sight of your face to scare off my patrons tomorrow.” He prodded in the bucket, turning over a few of the frogs. Age weathered Rory’s narrow brown face. His long fingers were constantly stained in the color of his latest tonic, and a permanent groove sat between his bushy brows. I called it his “rage stage,” because I could always gauge his level of fury by the number of furrows forming above his nose. Despite an old injury to his hip, his slenderness was not a sign of fragility. On the rare occasions when Rory smiled, it was clear he had been handsome in his youth. “If I find that you’ve layered the bottom with dirt again, I’m poisoning your tea.”

He pushed a haphazardly wrapped bundle into my arms. “Here.”

Bewildered, I turned the package over. “For me?”

He waved his cane around the empty shop. “Are you touched in the head, child?”

I carefully peeled the fabric back, half expecting it to explode in my face, and exposed a pair of beautiful golden gloves. Softer than a dove’s wing, they probably cost more than anything I could buy for myself. I lifted one reverently. “Rory, this is too much.”

I only barely stopped myself from putting them on. I laid them gingerly on the counter and hurried to scrub off my stained hands. There were no clean cloths left, so I wiped my hands on Rory’s tunic and earned a swat to the ear.

The fit of the gloves was perfect. Soft and supple, yielding with the flex of my fingers.

I lifted my hands to the lantern for closer inspection. These would certainly fetch a pretty price at market. Not that I’d sell them right away, of course. Rory liked pretending he had the emotional depth of a spoon, but he would be hurt if I bartered his gift a mere day later. Markets weren’t hard to find in Omal. The lower villages were always in need of food and supplies. Trading among themselves was easier than begging for scraps from the palace.

The old man smiled briefly. “Happy birthday, Sylvia.”

Sylvia. My first and favorite lie. I pressed my hands together. “A consolation gift for the spinster?” Not once in five years had Rory failed to remember my fabricated birth date.

“I should hardly think spinsterhood’s threshold as low as twenty years.”

In truth, I was halfway to twenty-one. Another lie.

“You are as old as time itself. The ages below one hundred must all look the same to you.”

He jabbed me with his cane. “It is past the hour for spinsters to be about.”

I left the shop in higher spirits. I pulled my cloak tight around my shoulders, knotting the hood beneath my chin. I had one more task to complete before I could finally reunite with my bed, and it meant delving deeper into the silent village. These were the hours when the mind ran free, when hollow masonry became the whispers of hungry shaiateen and the scratch of scuttling vermin the sounds of the restless dead.

I knew how sinuously fear cobbled shadows into gruesome shapes. I hadn’t slept a full night’s length in long years, and there were days when I trusted nothing beyond the breath in my chest and the earth beneath my feet. The difference between the villagers and me was that I knew the names of my monsters. I knew what they would look like if they found me, and I didn’t have to imagine what kind of fate I would meet.

Mahair was a tiny village, but its history was long. Its children would know the tales shared from their mothers and fathers and grandparents. Superstition kept Mahair alive, long after time had turned a new page on its inhabitants.

It also kept me in business.

Instead of turning right toward Raya’s keep, I ducked into the vagrant road. Bits of honey-soaked dough and grease marked the spot where the halawany’s daughters snacked between errands, sitting on the concrete stoop of their parents’ dessert shop. Dodging the dogs nosing at the grease, I checked for anyone who might report my movements back to Rory.

We had made a tradition of forgiving each other, Rory and me. Should he find out I was treating Omalians under his name, peddling pointless concoctions to those superstitious enough to buy them—well, I doubted Rory could forgive such a transgression. The “cures” I mucked together for my patrons were harmless. Crushed herbs and altered liquors. Most of the time, the ailments they were intended to ward off were more ridiculous than anything I could fit in a bottle.

The home I sought was ten minutes’ walk past Raya’s keep. Too close for comfort. Water dripped from the edge of the sagging roof, where a bare clothesline stretched from hook to hook. A pair of undergarments had fluttered to the ground. I kicked them out of sight. Raya taught me years ago how to hide undergarments on the clothesline by clipping them behind a larger piece of clothing. I hadn’t understood the need for so much stealth. I still didn’t. But time was a limited resource tonight, and I wouldn’t waste it soothing an Omalian’s embarrassment that I now had definitive proof they wore undergarments.

The door flew open. “Sylvia, thank goodness,” Zeinab said. “She’s worse today.”

I tapped my mud-encrusted boots against the lip of the door and stepped inside.

“Where is she?”

I followed Zeinab to the last room in the short hall. A wave of incense wafted over us when she opened the door. I fanned the white haze hanging in the air. A wizened old woman rocked back and forth on the floor, and bloody tracks lined her arms where nails had gouged deep. Zeinab closed the door, maintaining a safe distance. Tears swam in her large hazel eyes. “I tried to give her a bath, and she did this.” Zeinab pushed up the sleeve of her abaya, exposing a myriad of red scratch marks.

“Right.” I laid my bag down on the table. “I will call you when I’ve finished.”

Subduing the old woman with a tonic took little effort. I moved behind her and hooked an arm around her neck. She tore at my sleeve, mouth falling open to gasp. I dumped the tonic down her throat and loosened my stranglehold enough for her to swallow. Once certain she wouldn’t spit it out, I let her go and adjusted my sleeve. She spat at my heels and bared teeth bloody from where she’d torn her lip.

It took minutes. My talents, dubious as they were, lay in efficient and fleeting deception. At the door, I let Zeinab slip a few coins into my cloak’s pocket and pretended to be surprised. I would never understand Omalians and their feigned modesty. “Remember—”

Zeinab bobbed her head impatiently. “Yes, yes, I won’t speak a word of this. It has been years, Sylvia. If the chemist ever finds out, it will not be from me.”

She was quite self-assured for a woman who never bothered to ask what was in the tonic I regularly poured down her mother’s throat. I returned Zeinab’s wave distractedly and moved my dagger into the same pocket as the coins. Puddles of foul-smelling rain rippled in the pocked dirt road. Most of the homes on the street could more accurately be described as hovels, their thatched roofs shivering above walls joined together with mud and uneven patches of brick. I dodged a line of green mule manure, its waterlogged, grassy smell stinging my nose.

Did Omal’s upper towns have excrement in their streets?

Zeinab’s neighbor had scattered chicken feathers outside her door to showcase their good fortune to their neighbors. Their daughter had married a merchant from Dawar, and her dowry had earned them enough to eat chicken all month. From now on, the finest clothes would furnish her body. The choicest meats and hardest-grown vegetables for her plate. She’d never need to dodge mule droppings in Mahair again.

I turned the corner, absently counting the coins in my pocket, and rammed into a body.

I stumbled, catching myself against a pile of cracked clay bricks. The Nizahl soldier didn’t budge beyond a tightening of his frown.

“Identify yourself.”

Heavy wings of panic unfurled in my throat. Though our movements around town weren’t constrained by an official curfew, not many risked a late-night stroll. The Nizahl soldiers usually patrolled in pairs, which meant this man’s partner was probably harassing someone else on the other side of the village.

I smothered the panic, snapping its fluttering limbs. Panic was a plague. Its sole purpose was to spread until it tore through every thought, every instinct.

I immediately lowered my eyes. Holding a Nizahl soldier’s gaze invited nothing but trouble. “My name is Sylvia. I live in Raya’s keep and apprentice for the chemist Rory. I apologize for startling you. An elderly woman urgently needed care, and my employer is indisposed.”

From the lines on his face, the soldier was somewhere in his late forties. If he had been an Omalian patrolman, his age would have signified little. But Nizahl soldiers tended to die young and bloody. For this man to survive long enough to see the lines of his forehead wrinkle, he was either a deadly adversary or a coward.

“What is your father’s name?”

“I am a ward in Raya’s keep,” I repeated. He must be new to Mahair. Everyone knew Raya’s house of orphans on the hill. “I have no mother or father.”

He didn’t belabor the issue. “Have you witnessed activity that might lead to the capture of a Jasadi?” Even though it was a standard question from the soldiers, intended to encourage vigilance toward any signs of magic, I inwardly flinched. The most recent arrest of a Jasadi had happened in our neighboring village a mere month ago. From the whispers, I’d surmised a girl reported seeing her friend fix a crack in her floorboard with a wave of her hand. I had overheard all manner of praise showered on the girl for her bravery in turning in the fifteen-year-old. Praise and jealousy—they couldn’t wait for their own opportunities to be heroes.

“I have not.” I hadn’t seen another Jasadi in five years.

He pursed his lips. “The name of the elderly woman?”

“Aya, but her daughter Zeinab is her caretaker. I could direct you to them if you’d like.” Zeinab was crafty. She would have a lie prepared for a moment like this.

“No need.” He waved a hand over his shoulder. “On your way. Stay off the vagrant road.”

One benefit of the older Nizahl soldiers—they had less inclination for the bluster and interrogation tactics of their younger counterparts. I tipped my head in gratitude and sped past him.

A few minutes later, I slid into Raya’s keep. By the scent of cooling wax, it had not been long since the last girl went to bed. Relieved to find my birthday forgotten, I kicked my boots off at the door. Raya had met with the cloth merchants today. Bartering always left her in a foul mood. The only acknowledgment of my birthday would be a breakfast of flaky, buttery fiteer and molasses in the morning.

When I pushed open my door, a blast of warmth swept over me. Baira’s blessed hair, not again. “Raya will have your hides. The waleema is in a week.”

Marek appeared engrossed in the firepit, poking the coals with a thin rod. His golden hair shone under the glow. A mess of fabric and the beginnings of what might be a dress sat beneath Sefa’s sewing tools. “Precisely,” Sefa said, dipping a chunk of charred beef into her broth. “I am drowning my sorrows in stolen broth because of the damned waleema. Look at this dress! This is a dress all the other dresses laugh at.”

“What is he doing with the fire?” I asked, electing to ignore her garment-related woes. Come morning, Sefa would hand Raya a perfect dress with a winning smile and bloodshot eyes. An apprenticeship under the best seamstress in Omal wasn’t a role given to those who folded under pressure.

“He’s trying to roast his damned seeds.” Sefa sniffed. “We made your room smell like a tavern kitchen. Sorry. In our defense, we gathered to mourn a terrible passing.”

“A passing?” I took a seat beside the stone pit, rubbing my hands over the crackling flames.

Marek handed me one of Raya’s private chalices. The woman was going to skin us like deer. “Ignore her. We just wanted to abuse your hearth,” he said. “I am convinced Yuli is teaching his herd how to kill me. They almost ran me right into a canal today.”

“Did you do something to make Yuli or the oxen angry?”

“No,” Marek said mournfully.

I rolled the chalice between my palms and narrowed my eyes. “Marek.”

“I may have used the horse’s stalls to… entertain…” He released a long-suffering sigh. “His daughter.”

Sefa and I released twin groans. This was hardly the first time Marek had gotten himself in trouble chasing a coy smile or kind word. He was absurdly pretty, fair-haired and green-eyed, lean in a way that undersold his strength. To counter his looks, he’d chosen to apprentice with Yuli, Mahair’s most demanding farmer. By spending his days loading wagons and herding oxen, Marek made himself indispensable to every tradesperson in the village. He worked to earn their respect, because there were few things Mahair valued more than calloused palms and sweat on a brow.

It was also why they tolerated the string of broken hearts he’d left in his wake.

Not one to be ignored for long, Sefa continued, “Your youth, Sylvia, we mourn your youth! At twenty, you’re having fewer adventures than the village brats.”

I drained the water, passing the chalice to Marek for more. “I have plenty of adventure.”

“I’m not talking about how many times you can kill your fig plant before it stays dead,” Sefa scoffed. “If you had simply accompanied me last week to release the roosters in Nadia’s den—”

“Nadia has permanently barred you from her shop,” Marek interjected. Brave one, cutting Sefa off in the middle of a tirade. He scooped up a blackened seed, throwing it from palm to palm to cool. “Leave Sylvia be. Adventure does not fit into a single mold.”

Sefa’s nostrils flared wide, but Marek didn’t flinch. They communicated in that strange, silent way of people who were bound together by something thicker than blood and stronger than a shared upbringing. I knew because I had witnessed hundreds of their unspoken conversations over the last five years.

“I am not killing my fig plant.” I pushed to my feet. “I’m cultivating its fighter’s spirit.”

“Stop glaring at me,” Marek said to Sefa with a sigh. “I’m sorry for interrupting.” He held out a cracked seed.

Sefa let his hand dangle in the air for forty seconds before taking the seed. “Help me hem this sleeve?”

With a sheepish grin, Marek offered his soot-covered palms. Sefa rolled her eyes.

I observed this latest exchange with bewilderment. It never failed to astound me how easily they existed around one another. Their unusual devotion had led to questions from the other wards at the keep. Marek laughed himself into stitches the first time a younger girl asked if he and Sefa planned to wed. “Sefa isn’t going to marry anyone. We love each other in a different way.”

The ward had batted her lashes, because Marek was the only boy in the keep, and he was in possession of a face consigning him to a life of wistful sighs following in his wake.

“What about you?” the ward had asked.

Sefa, who had been smiling as she knit in the corner, sobered. Only Raya and I saw the sorrowful look she shot Marek, the guilt in her brown eyes.

“I am tied to Sefa in spirit, if not in wedlock.” Marek ruffled the ward’s hair. The girl squealed, slapping at Marek. “I follow where she goes.”

To underscore their insanity, the pair had taken an instant liking to me the moment Rory dropped me off at Raya’s doorstep. I was almost feral, hardly fit for friendship, but it hadn’t deterred them. I adjusted poorly to this Omalian village, perplexed by their simplest customs. Rub the spot between your shoulders and you’ll die early. Eat with your left hand on the first day of the month; don’t cross your legs in the presence of elders; be the last person to sit at the dinner table and the first one to leave it. It didn’t help that my bronze skin was several shades darker than their typical olive. I blended in with Orbanians better, since the kingdom in the north spent most of its days under the sun. When Sefa noticed how I avoided wearing white, she’d held her darker hand next to mine and said, “They’re jealous we soaked up all their color.”

Matters weren’t much easier at home. Everyone in the keep had an ugly history haunting their sleep. I didn’t help myself any by almost slamming another ward’s nose clean off her face when she tried to hug me. Despite the two-hour lecture I endured from Raya, the incident had firmly established my aversion to touch.

For some inconceivable reason, Sefa and Marek weren’t scared off. Sefa was quite upset about her nose, though.

I hung my cloak neatly inside the wardrobe and thumbed the moth-eaten collar. It wouldn’t survive another winter, but the thought of throwing it away brought a lump to my throat. Someone in my position could afford few emotional attachments. At any moment, a sword could be pointed at me, a cry of “Jasadi” ending this identity and the life I’d built around it. I recoiled from the cloak, curling my fingers into a fist. I promptly tore out the roots of sadness before it could spread. A regular orphan from Mahair could cling to this tired cloak, the first thing she’d ever purchased with her own hard-earned coin.

A fugitive of the scorched kingdom could not.

I turned my palms up, testing the silver cuffs around my wrists. Though the cuffs were invisible to any eye but mine, it had taken a long time for my paranoia to ease whenever someone’s idle gaze lingered on my wrists. They flexed with my movement, a second skin over my own. Only my trapped magic could stir them, tightening the cuffs as it pleased.

Magic marked me as a Jasadi. As the reason Nizahl created perimeters in the woods and sent their soldiers prowling through the kingdoms. I had spent most of my life resenting my cuffs. How was it fair that Jasadis were condemned because of their magic but I couldn’t even access the thing that doomed me? My magic had been trapped behind these cuffs since my childhood. I suppose my grandparents couldn’t have anticipated dying and leaving the cuffs stuck on me forever.

I hid Rory’s gift in the wardrobe, beneath the folds of my longest gown. The girls rarely risked Raya’s wrath by stealing, but a desperate winter could make a thief of anyone. I stroked one of the gloves, fondness curling hot in my chest. How much had Rory spent, knowing I’d have limited opportunities to wear them?

“We wanted to show you something,” Marek said. His voice hurtled me back to reality, and I slammed the wardrobe doors shut, scowling at myself. What did it matter how much Rory spent? Anything I didn’t need to survive would be discarded or sold, and these gloves were no different.

Sefa stood, dusting loose fabric from her lap. She snorted at my expression. “Rovial’s tainted tomb, look at her, Marek. You might think we were planning to bury her in the woods.”

Marek frowned. “Aren’t we?”

“Both of you are banned from my room. Forever.”

I followed them outside, past the row of fluttering clotheslines and the pitiful herb garden. Built at the top of a grassy slope, Raya’s keep overlooked the entire village, all the way to the main road. Most of the homes in Mahair sat stacked on top of each other, forming squat, three-story buildings with crumbling walls and cracks in the clay. The villagers raised poultry on the roofs, nurturing a steady supply of chickens and rabbits that would see them through the monthly food shortages. Livestock meandered in the fields shouldering Essam Woods, fenced in by the miles-long wall surrounding Mahair.

Past the wall, darkness marked the expanse of Essam Woods. Moonlight disappeared over the trees stretching into the black horizon.

Ahead of me, Marek and Sefa averted their gaze from the woods. They had arrived in Mahair when they were sixteen, two years before me. I couldn’t tell if they’d simply adopted Mahair’s peculiar customs or if those customs were more widespread than I thought.

The day after I emerged from Essam, I’d spent the night sitting on the hill and watching the spot where Mahair’s lanterns disappeared into the empty void of the woods. Escaping Essam had nearly killed me. I’d wanted to confirm to myself that this village and the roof over my head weren’t a cruel dream. That when I closed my eyes, I wouldn’t open them to branches rustling below a starless sky.

Raya had stormed out of the keep in her nightgown and hauled me inside, where I’d listened to her harangue me about the risk of staring into Essam Woods and inviting mischievous spirits forward from the dark. As though my attention alone might summon them into being.

I spent five years in those woods. I wasn’t afraid of their darkness. It was everything outside Essam I couldn’t trust.

“Behold!” Sefa announced, flinging her arm toward a tangle of plants.

We stopped around the back of the keep, where I had illicitly shoveled the fig plant I bought off a Lukubi merchant at the last market. I wasn’t sure why. Nurturing a plant that reminded me of Jasad, something rooted I couldn’t take with me in an emergency—it was embarrassing. Another sign of the weakness I’d allowed to settle.

My fig plant’s leaves drooped mournfully. I prodded the dirt. Were they mocking my planting technique?

“She doesn’t like it. I told you we should have bought her a new cloak,” Marek sighed.

“With whose wages? Are you a wealthy man now?” Sefa peered at me. “You don’t like it?”

I squinted at the plant. Had they watered it while I was gone? What was I supposed to like? Sefa’s face crumpled, so I hurriedly said, “I love it! It is, uh, wonderful, truly. Thank you.”

“Oh. You can’t see it, can you?” Marek started to laugh. “Sefa forgot she is the size of a thimble and hid it out of your sight.”

“I am a perfectly standard height! I cannot be blamed for befriending a woman tall enough to tickle the moon,” Sefa protested.

I crouched by the plant. Wedged behind its curtain of yellowing leaves, a woven straw basket held a dozen sesame-seed candies. I loved these brittle, tooth-chipping squares. I always made a point to search for them at market if I’d saved enough to spare the cost.

“They used the good honey, not the chalky one,” Marek added.

“Happy birthday, Sylvia,” Sefa said. “As a courtesy, I will refrain from hugging you.”

First Rory, now this? I cleared my throat. In a village of empty stomachs and dying fields, every kindness came at a price. “You just wanted to see me smile with sesame in my teeth.”

Marek smirked. “Ah, yes, our grand scheme is unveiled. We wanted to ruin your smile that emerges once every fifteen years.”

I slapped the back of his head. It was the most physical contact I could bear, but it expressed my gratitude.

We walked back to the keep and resettled around the extinguished firepit. Marek dug through the ash for any surviving seeds. Sefa lay back on the ground, her feet propped on Marek’s leg. “Arin or Felix?”

I slumped on my bed and set to the tedious task of coaxing my curls out of their knotted disaster of a braid. The sesame-seed candies were nestled safely in my wardrobe. The timing of these gifts could not have been better. As soon as Sefa and Marek fell asleep, I would collect what I needed for my trip back to the woods.

“Are names of the Nizahl and Omal Heirs.”

“Sylvia,” Sefa wheedled, tossing a seed at my forehead. “You have been selected to attend the Victor’s Ball on the arm of an Heir. Arin or Felix?”

Marek groaned, throwing his elbow over his eyes. Soot smeared the corners of his mouth. Neither of us understood why Sefa loved dreaming up intrigues of far-flung courts. She claimed

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...