- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

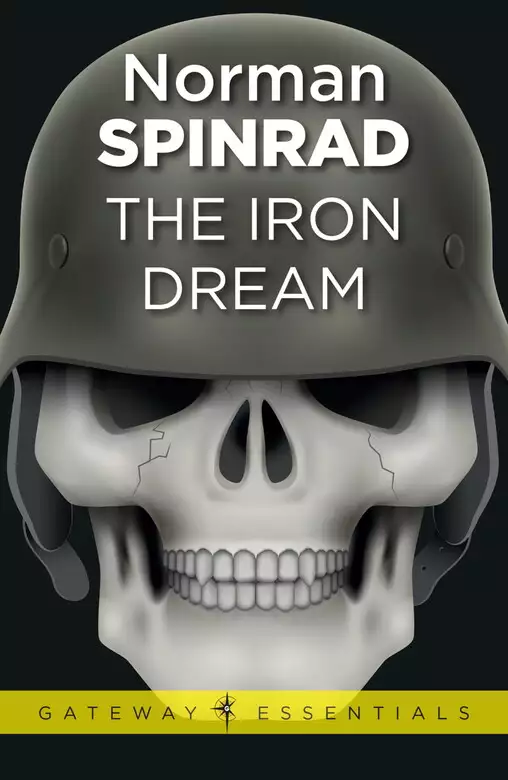

Norman Spinrad's 1972 alternate history, gives us both a metafictional what-if novel and a cutting satire of one of the 20th century's most evil regimes . . . In 1919, a young Austrian artist by the name of Adolf Hitler immigrated to the United States to become an illustrator for the pulp magazines and, eventually, a Hugo Award-winning SF author. This volume contains his greatest work, Lord of the Swastika : an epic post-apocalyptic tale of genetic 'trueman' Feric Jagger and his quest to purify the bloodline of humanity by ruthlessly slaughtering races of the genetically impure - a quest Norman Spinrad expertly skewers through ironic imagery and over-the-top rhetoric. Spinrad hoped to expose some unpalatable truths about much of SF and Fantasy literature and its uncomfortable relationship with fascist ideologies - an aim that was not always apparent to neo-fascist readers. In order to make his aims clear to the hard-of-understanding, Spinrad added an imaginary critical analysis by a fictional literary scholar, Homer Whipple, of New York University.

Release date: June 30, 2014

Publisher: Gateway

Print pages: 288

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Iron Dream

Norman Spinrad

Let Adolf Hitler transport you to a far-future Earth, where only FERIC JAGGAR and his mighty weapon, the Steel Commander, stand between the remnants of true humanity and annihilation at the hands of the totally evil Dominators and the mindless mutant hordes they completely control.

Lord of the Swastika is recognized as the most vivid and popular of Hitler’s science Fiction novels by fans the world over, who honored it with a Hugo as Best Science Fiction Novel of 1954. Long out of print, it is now once more available in this new edition, with an Afterword by Homer Whipple of New York University. See for yourself why so many people have turned to this science-fantasy novel as a beacon of hope in these grim and terrifying times.

Other Science fiction Novels by Adolf Hitler

EMPEROR OF THE ASTEROIDS

THE BUILDERS OF MARS

FIGHT FOR THE STARS

THE TWILIGHT OF TERRA

SAVIOR FROM SPACE

THE MASTER RACE

THE THOUSAND YEAR RULE

THE TRIUMPH OF THE WILL

TOMORROW THE WORLD

About the Author

Adolf Hitler was born in Austria on April 20, 1889.

As a young man he migrated to Germany and served in the German army during the Great War. After the war, he dabbled briefly in radical politics in Munich before finally emigrating to New York in 1919. While learning English, he eked out a precarious existence as a sidewalk artist and occasional translator in New York’s bohemian haven, Greenwich Village. After several years of this freewheeling life, he began to pick up odd jobs as a magazine and comic illustrator. He did his first interior illustration for the science fiction magazine Amazing in 1930. By 1932, he was a regular illustrator for the science fiction magazines, and, by 1935, he had enough confidence in his English to make his debut as a science fiction writer. He devoted the rest of his life to the science fiction genre as a writer, illustrator, and fanzine editor. Although best known to present-day SF fans for his novels and stories. Hitler was a popular illustrator during the Golden Age of the thirties, edited several anthologies, wrote lively reviews, and published a popular fanzine, Storm, for nearly ten years.

He won a posthumous Hugo at the 1955 World Science fiction Convention for Lord of the Swastika, which was completed just before his death in 1953. For many years, he had been a popular figure at SF conventions, widely known in science fiction fandom as a wit and nonstop raconteur. Ever since the book’s publication, the colorful costumes he created in Lord of the Swastika have been favorite themes at convention masquerades.

Hitler died in 1953, but the stories and novels he left behind remain as a legacy to all science fiction enthusiasts.

With a great groaning of tired metal and a hiss of escaping steam, the roadsteamer from Gormond came to a halt in the grimy yard of the Pormi depot, a mere three hours late; quite a respectable performance by Borgravian standards. Assorted, roughly humanoid, creatures shambled from the steamer displaying the usual Borgravian variety of skin hues, body parts, and gaits. Bits of food from the more or less continuous picnic that these mutants had held throughout the twelve-hour trip clung to their rude and, for the most part, threadbare clothing. A sour stale odor clung to this gaggle of motley specimens as they scuttled across the muddy courtyard toward the unadorned concrete shed that served as a terminal.

Finally, there emerged from the cabin of the steamer a figure of startling and unexpected nobility: a tall, powerfully built true human in the prime of manhood. His hair was yellow, his skin was fair, his eyes were blue and brilliant. His musculature, skeletal structure, and carriage were letter-perfect, and his trim blue tunic was clean and in good repair.

Feric Jaggar looked every inch the genotypically pure human that he in fact was. It was all that made such prolonged close confinement with the dregs of Borgravia bearable; the quasi-men could not help but recognize his genetic purity. The sight of Feric put mutants and mongrels in their place, and for the most part they kept to it.

Feric carried his worldly possessions in a leather bag which he hefted easily; this enabled him to avoid the grubby terminal entirely and embark directly upon Ulm Avenue which led through the foul little border town toward the bridge over the Ulm by the shortest route possible. Today he would at last put the Borgravian warrens behind him and claim his birthright as a genotypically pure human and a Helder, with a spotless pedigree that was traceable back for twelve generations.

With his heart filled with thoughts of his goal in fact and in spirit, Feric was almost able to ignore the sordid spectacle that assailed his eyes, ears, and nostrils as he loped up the bare earth boulevard toward the river. Ulm Avenue was little more than a muddy ditch between two rows of rude shacks constructed for the most part of crudely dressed timber, wattle, and rusted sheet-steel.

Nevertheless, this singularly unimpressive track was apparently the pride and joy of the denizens of Pormi, for the fronts of these filthy buildings were festooned with all manner of garish lettering and rude illustrations advertising the goods to be had within, mostly local produce, or the castoff artifacts of the higher civilization across the Ulm.

Moreover, many of the shopkeepers had set up street stands purveying rotten-looking fruit, grimy vegetables, and fly-specked meat; these fetid goods they hawked at the top of their lungs to the creatures which thronged the street, who in turn added to the din with shrill and argumentative cajolery.

The rank odor, raucous jabbering, and generally unwholesome atmosphere reminded Feric of the great marketplace area of Gormond, the Borgravian capital, where fate had confined him for so many years. As a child, he had been shielded from close contact with the environs of the native quarter; as a young man he had taken great pains, and at no little expense, to avoid such places as much as was practicable.

Of course it had never been possible to avoid the sight of the sorts of mutants who crowded every nook and cranny of Gormond, and the gene pool here in Pormi appeared not one whit less debased than that which prevailed in the Borgravian capital. The skins of the street rabble here, as in Gormond, were a crazy quilt of mongrelized mutations. Blueskins, Lizardmen, Harlequins, and Bloodfaces were the least of it; at least it could be said that such creatures bred true to their own kind. But all sorts of mixtures prevailed – the scales of a Lizardman might be tinted blue or purple instead of green; a Blueskin might have the mottling of a Harlequin; the warted countenance of a Toadman might be an off-shade of red.

The grosser mutations for the most part bred truer, if only because two such genetic catastrophes in the same creature ended more often than not in an unviable fetus.

Many of the shopkeepers here in Pormi were dwarfs of one kind or another – hunchbacked, covered with wiry black hair, slightly pinheaded, many with secondary skin mutations – incapable of more strenuous labor. In a small town such as this, the more arcane mutants were less in evidence than in what passed for a Borgravian metropolis.

Still, as Feric elbowed his way through the foul-smelling crowds, he spotted three Eggheads, their naked chitinous skulls gleaming redly in the warm sun, and brushed against a Parrotface. This creature whirled about at Feric’s touch, clacking its great bony beak at him indignantly for a moment until it recognized him for what he was.

Then, of course, the Parrotface lowered its rheumy gaze, instantly gave off flapping its obscenely mutated teeth, and muttered a properly humble “Your pardon, Trueman.”

For his part, Feric did not acknowledge the creature one way or the other, and quickly continued on up the street staring determinedly straight ahead.

However, a few dozen yards up the street, a familiar floating feeling wafted gently through Feric’s mind; this indeed gave him pause, for long experience had taught him that this psychic aura was sure indication that a Dominator was in the area. Sure enough, when Feric studied the row of shacks to his right, his eyes confirmed the proximity of a Dom, and the dominance pattern was hardly the subtlest he had ever encountered either.

Five stalls sat on the street all in a line, presided over by three dwarfs, a Blueskin-Toadman mongrel with warty blue skin, and a Lizardman. All of these creatures displayed the slackness of expression and deadness of eye characteristic of mutants captured in a long-standing dominance pattern. The stalls themselves held meat, fruit, and vegetables in a loathsome state of advanced decay that should have rendered them totally unsalable, even by Borgravian standards. Nevertheless, hordes of mongrels and mutants flocked around these stands, snapping up the putrid goods at inflated prices without so much as a moment’s haggling.

Only the presence of a Dominator in the vicinity could account for such behavior. Gormond was richly infested with the monstrosities, since they naturally preferred large cities where victims abounded; that such a minor town as this was infected was clear indication to Feric that Borgravia was even further under the spell of Zind than he had imagined.

His immediate impulse was to pause, seek out the Dom, and wring the monster’s neck, but upon a moment’s reflection, he decided that freeing a few wretched and worthless mutants from a dominance pattern was not really worth delaying his long-awaited exit from the cesspit of Borgravia a moment longer. Therefore, he continued on his way.

At last, the street petered out and became a path through an unwholesome grove of stunted pine trees with purplish needles and twisted trunks covered with cankers.

Though this could hardly be described as a scene of beauty, it was certainly a welcome respite from the boisterous foulness of the town itself. Shortly, the path turned slightly to the north, and began to parallel the south bank of the Ulm.

Here Feric paused to stare northward across the wide calm waters of the river which demarked this section of the border between the fester of Borgravia and the High Republic of Heldon. Across the Ulm, the stately, genotypically pure oaks of the Emerald Wood marched in wooden ranks to the north bank of the river. To Feric, these genetically spotless trees growing out of the rich, uncontaminated black soil of Heldon epitomized what the High Republic stood for in an otherwise mongrelized and degenerate earth. As the Emerald Wood was a forest of genetically pure trees, so was Heldon itself a forest of genetically pure men, standing like a palisade against the mutated monstrosities of the genetic garbage heaps that surrounded the High Republic.

As he proceeded farther up the path, the Ulm bridge became visible, a graceful arch of hewn stone and oiled stainless steel, an obvious product of superior Helder craftsmanship. Feric hastened his stride, and was soon able to note with satisfaction that Heldon had forced the wretched Borgravians to accept the humiliation of a Helder customs fortress on the Borgravian end of the bridge. The black, red, and white building astride the entrance to the bridge was painted in the Helder colors in lieu of a proper flag, but to Feric it still proudly proclaimed that no near-man would be permitted to contaminate an inch of pure human soil. As long as Heldon kept itself genetically pure and rigorously enforced its racial purity laws, the hope still lived that the earth might once again be the sole property of the true human race.

Several paths from various directions converged on the customs fortress and, strangely enough, a sorry collection of mongrels and mutants were queued up outside the public portal, which was guarded by two purely ceremonial customs troops, armed only with standard-issue steel truncheons. It was a peculiar business indeed, for most of these creatures had no hope of passing a cursory examination by a blind moron. An obvious Lizardman stood right behind a creature whose legs had an extra joint. There were Blueskins and humpback dwarfs, an Egghead, and mongrels of all kinds; in short, a typical cross section of Borgravian citizenry. What deluded these poor devils into supposing that their like would be permitted to cross the bridge into Heldon? Feric wondered as he took his place in line behind a plain-dressed Borgravian with no apparent genetic defect.

For his own part, Feric was more than prepared for the thorough genetic examination he would have to undergo before being certified a pure human and admitted to the High Republic; he welcomed the ordeal and heartily approved of its stringency. Although his spotless pedigree virtually assured certification, he had, at some pains and no little expense, verified his genetic purity beforehand – or at least done so to the extent possible in a country inhabited chiefly by mutants and mutant-human mongrels, where, no doubt, the genetic analysts themselves were thoroughly contaminated. Had both his parents not held certificates, had his pedigree not been spotless for ten generations, had he not been conceived in Heldon itself, though forced by the banishing of his father for so-called war crimes to endure a birth in Borgravia, Feric would not have dared to presume to seek admittance to the spiritual and racial homeland he had never seen. Though instantly acknowledged as a true man on sight throughout Borgravia and verified as such by what passed for genetic science in that mongrelized state, he eagerly looked forward to the only confirmation of his genetic purity that really counted: acceptance as a citizen by the High Republic of Heldon, sole bastion of the true genotype of man.

Why then did such patently contaminated material presume to attempt to pass Helder customs? The Borgravian in front of him was a fair example. True his surface veneer of genetic purity was marred only by an acrid chemical odor exuded by his skin, but such an obvious somatic aberration was sure indication of thoroughly contaminated genetic material. The Helder genetic analyst would spot it in an instant, even without recourse to instruments. The Treaty of Karmak had forced Heldon to open its borders, but only to certifiable humans. Perhaps the answer was merely the pathetic desire of even the most genetically debased mongrel to gain admittance to the brotherhood of true men, a desire sometimes strong enough to override reason or the truth in the mirror.

At any rate, the queue was moving along quite swiftly into the customs fortress; no doubt very rapid processing and rejection of most of the Borgravians was taking place inside. It was not long before Feric passed by the portal guards, through the portal itself, and stood on what might in a sense be regarded as Helder soil for the first time in his life.

The interior of the customs fortress was unmistakably Helder, in sharp contrast to everything else south of the Ulm, where unfortunate circumstance had confined Feric during his growth to manhood. The large antechamber had a floor of smart red, black, and white tile, and similarly styled paintwork embellished the polished oaken walls. The chamber was brightened by powerful electric globes. What a far cry from the crudely finished, poured concrete interiors and tallow candles of the typical Borgravian public building!

A few yards inside the portal, a Helder customs guard in a somewhat slovenly gray uniform with tarnished brasswork divided the queue into two streams. All the more obvious mutants and mongrels were directed across the chamber and out through a door in the far wall. Feric approved heartily – there was no point in wasting the time of a genetic analyst with shambling quasi-humans such as these. An ordinary customs guard was quite qualified to dismiss them without further examination. The smaller number of hopefuls that the guard directed through a nearer door included quite a number of very dubious cases, such as the foul-smelling Borgravian who preceded Feric, but nothing on the order of a Blueskin or Parrotface.

However, as he approached the guard, Feric noticed a strange and disquieting thing. The guard seemed to nod to a good many of the mutants he guided into the reject line as if acknowledging familiarity; moreover, the Borgravians themselves acted as if they knew the drill, and, strangest of all uttered not a word of protest at their exclusion, indeed displayed little emotion at all. Could it be that these sorry creatures were all so below the human genotype in intelligence that they were incapable of retaining memories for more than a day or so and thus returned day after day ritualistically? Feric had heard that such fixated behavior was not unknown in the real genetic sinkholes of Cressia and Arbona, but he had never observed anything of the like in Borgravia, where the gene pool was constantly enriched by the exile of native-born Helder who could not quite be certified true humans, but who certainly were close enough to bring the level of the Borgravian gene pool far above that of places like Arbona or Zind.

As Feric reached the head of the queue, the customs guard addressed him in a flat, rather bored tone. “Day pass, citizen, or citizen candidate?”

“Citizen candidate,” Feric replied crisply. Surely the only conceivable pass into Heldon was an official certificate of genetic purity! Either you already held Helder citizenship or you applied for certification and were found pure or you were refused admission to Heldon. What was this impossible third category?

The guard directed Feric into the smaller line with no more significant a gesture than the slack nodding of his head in the indicated direction. There was a pattern in all this, something about the whole tone of the operation, that Feric found profoundly disturbing, a wrongness that seemed to hover in the air, a deadness, a definite lack of the traditional Helder snap and dash. Had their daily isolation on the Borgravian side of the Ulm had some subtle detrimental effect on the esprit and will of these genetically robust Helder?

Wrapped in these somewhat somber musings, Feric followed the queue through the indicated doorway and into a long narrow room paneled in pine set off tastefully with ornately carved wooden trim depicting typical scenes from the Emerald Wood. A counter of black stone, polished to a high gloss and accented with inlaid stainless steel, ran down the length of the room, separating the queue from the four Helder customs officers who stood behind it.

These fellows seemed fine specimens of true humanity, but their uniforms were somewhat slovenly, and a certain proper soldierliness was absent from their bearing. They looked more like clerks in a money depository or a public post office than customs troops manning a citadel of genetic purity.

Feric’s uneasiness grew as the sour-reeking Borgravian preceding him finished his short interview with the first of the officers, wiped fingerprint ink off his hands with a rather soiled cloth, and followed the queue on down the line to the next Helder official. At the far end of the long room, Feric perceived the entrance to the bridge itself, where a guard armed with a truncheon and a pistol seemed to be passing an extremely dubious collection of genetic baggage on through to Heldon. In fact there was an insane perfunctory air about the whole operation.

The first Helder officer was young, blond, and a prime example of the true human genotype; moreover, though Feric sensed a certain laxness in his demeanor, his uniform was better tailored than most of the others Feric had noticed, freshly pressed, and the brasswork was at least untarnished, if not exactly gleaming. Before him on the shiny black counter were a pile of forms, a scriber, a blotter, a soiled scrap of cloth, and an inkpad.

The officer looked Feric straight in the eye, but the manliness of his gaze lacked a certain conviction. “Do you hold a certificate of genetic purity issued by the High Republic of Heldon?” he asked formally.

“I am applying for certification and admission to the High Republic as a Citizen and a true man,” Feric replied with a dignity he hoped was sufficient to the occasion.

“So,” the officer muttered diffidently, reaching for his scriber and the top form on the pile, and averting his blue eyes from Feric’s person. “Let us dispose of the formalities. Name?”

“Feric Jaggar,” Feric answered proudly, hoping for a flicker of recognition. For although Heermark Jaggar had only been a cabinet subofficial at the time of the peace of Karmak, there were surely those in the fatherland who still revered the names of the martyrs of Karmak. But the guard showed no recognition of the honor implicit in Feric’s pedigree and wrote the name on the form in a casual, even somewhat imprecise hand.

“Place of birth?”

“Gormond, Borgravia.”

“Present citizenship?”

Feric winced somewhat as he was forced to admit his technical Borgravian nationality. “However,” he felt constrained to add, “both my parents were native Helder, certificate holders, and pure humans. My father was Heermark Jaggar, who, served as undersecretary of genetic evaluation during the Great War.”

“Surely you realize that not even the most illustrious pedigree can guarantee even a native-born Helder certification as a true man.”

Feric’s fair skin reddened. “I merely wish to point out that my father was exiled not for genetic contamination but for service to Heldon. Like many other good Helder, he was victimized by the loathsome Treaty of Karmak.”

“It’s none of my affair,” the officer replied, inking Feric’s fingertips and applying them to the proper boxes engraved on the form. “I’m not much interested in politics.”

“Genetic purity is the politics of human survival!” Feric snapped.

“I suppose it is,” the officer muttered inanely, handing him the odious ink rag, contaminated by the fingers of the mongrel in the queue before him – and by fate only knew how many others before that. Feric gingerly removed the ink from his fingers as best he could with a small unsoiled comer of the rag, while the young officer passed his form along to the Helder on his right.

This officer was an older man with trimly cropped gray hair and a dignified waxed mustache; obviously he had been an impressive figure in his prime. Now his eyes were red and rheumy as if from fatigue, and his shoulders stooped as if with the actual physical weight of the tremendous responsibility they metaphorically bore, for on the shoulder of his tunic was the red caduceus in the black fist emblematic of the genetic analyst. The analyst glanced at the form, then spoke in a diffident voice, without looking directly at Feric.

“Trueman Jaggar, I am Dr. Heimat. It will be necessary to perform certain tests before issuing you a certificate of genetic purity.”

Feric could scarcely credit his ears. What sort of genetic analyst was this that would so state the obvious while implicitly granting him the honorific of “Trueman” beforehand? Where was their sufficient cause to explain the slackness and incredible lack of rigor in the bearing and manner of the men manning this customs fortress?

Heimat passed the form to the underling at his right, a somewhat slender, fair young man with chestnut hair bearing the ensign of a scribe on his uniform. As the paper was handed over, Feric’s attention was momentarily drawn to this scribe, and his puzzlement was instantly resolved in the most horrifying manner conceivable.

For although the scribe appeared genetically pure to all but the highly sensitized eye, Feric knew for a certainty that this was a Dom!

He could not have precisely specified the characteristics of the scribe which marked him as a Dominator, but the total gestalt of the creature’s presence fairly shrieked Dom at him through all his known and perhaps several unknown senses: a certain rodential gleam in the creature’s eyes, a subtle smugness about his bearing. Perhaps there were other guideposts that Feric perceived on an entirely subliminal level: a wrongness in the body odor detectable only to the back reaches of his brain, an actual broadcast of electromagnetic energy subtle enough to arouse his suspicion even though the dominance field was not being directed at his own person. Perhaps it was simply that Feric, a true man isolated for the most part among mutants and mongrels in a land heavily influenced by the Doms, had developed a psychic sensitivity to their presence that Helder who dwelt among their own kind lacked. At any rate, though constantly exposed to Dominators throughout his life, Feric had never been snared in a Dom’s mental net, though at times his will had been severely taxed. This continuous exposure certainly enabled him to sniff out a Dom, whatever the subtleties of his method might be.

And standing there before him with scriber and form in hand at the very shoulder of a Helder genetic analyst in a most critical position was one of the loathsome creatures!

It explained everything. The whole garrison must be ensnared in varying degrees in the dominance pattern that this seemingly insignificant scribe had no doubt slowly and painstakingly constructed. It was monstrous! But what could be done? How could men trapped in the dominance net themselves be convinced of the presence of their master?

Heimat had a small panoply of his science’s paraphernalia out before him, but it seemed a paltry display; the Borgravian quack he had been forced to settle for in Gormond had employed a broader spectrum of tests than the Helder had equipped himself to perform.

He handed Feric a large blue balloon. “Breathe into this, please,” he said. “It’s been chemically treated so that only the biochemical breath-profile associated with the pure human genotype will turn it green.”

Feric exhaled into, the balloon, knowing full well that this was one of the most basic of tests; innumerable mongrels had been known to have passed it, and, moreover, it was totally ineffective in weeding out Doms.

Presently, the balloon turned a bright green. “Breath analysis – positive,” Heimat called out, and the Dominator scribe, without looking at either of them, made the appropriate mark on the form.

The analyst handed Feric a glass vial. “Expectorate into this, please. I will subject the composition of your saliva to chemical analysis.”

Feric spat into the vial, wishing fervently that it were the face of the Dominator, who now looked up and stared at him with an infuriatingly feigned mildness.

Dr. Heimat diluted the saliva with water, then pipetted a bit of the liquid into each of a rack of ten glass tubes.

From a series of bottles, he decanted various chemicals into the tubes, so that the clear liquid in each turned colors: black, aqua, yellow, brick-orange, aqua again, red, once more yellow, yet again aqua, purple, and opaque white.

“Saliva analysis – one hundred percent perfect,” the genetic analyst called out. This test, taking ten separate characteristics of pure human saliva separately as genetic criteria rather than merely testing the total biochemical gestalt, had perforce a much greater precision. However, there were dozens of mutations from the true human norm that were in no way linked to the composition of saliva or breath, including the Dominator mutation itself, which could not be smelled out by somatic tests at all.

Feric glared at the Dominator, daring the creature to test his will and reveal his true colors. But of course the scribe directed no psychic energies in his direction. Why should he expose himself to a passing stranger and thus risk the dissolution of his dominance pattern, when circumstances foreclosed the possibility of adding him to the string?

Dr. Heimat affixed the twin electrodes of a P-meter to the skin of Feric’s right palm with a gummy vegetable adhesive. The P-meter consisted of a. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...