- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

-

- Edit description

- View all marketing texts

Far off the edge of human existence, beside a dying star lies a nameless ship abandoned and hidden, lost for a millennium. But there are secrets there, terrible secrets that would change the fate of humanity, and eventually someone will come looking.

Refugee, criminal and linguist Sean Wren is made an offer he knows he can’t refuse: life in prison, “voluntary” military service – or salvaging data in a long-dead language from an abandoned ship filled with traps and monsters, just days before it’s destroyed in a supernova. Data connected to the Philosopher’s Stone experiments, into unlocking the secrets of immortality.

And he’s not the only one looking for the derelict ship. The Ministers, mysterious undying aliens that have ruled over humanity for centuries, want the data – as does The Republic, humanity’s last free government. And time is running out.

In the bowels of the derelict ship, surrounded by horrors and dead men, Sean slowly uncovers the truth of what happened on the ship, in its final days… and the terrible secret it’s hiding.

Release date: October 11, 2022

Publisher: Rebellion Publishing Ltd

Print pages: 468

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

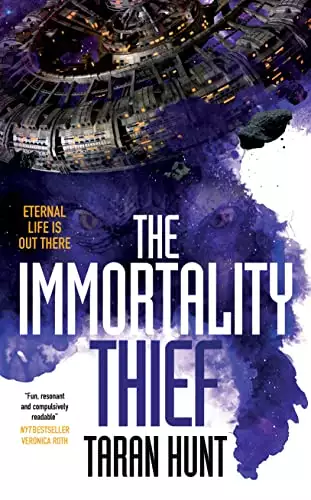

The Immortality Thief

Taran Hunt

CHAPTER ONE:THE NAMELESS SHIP AND THE DYING STAR

The nothing-place between leaving and arriving during faster-than-light travel isn’t really Hell. Hell is the absence of God, or the absence of other people, or something like that. FTL engines just… I don’t know, grabbed space and yanked it forward, rippling like a bedsheet tugged out of place, and our ship caught up in the folds.

But it sure as Hell felt like Hell. In the moment between the kick to faster-than-light speeds, and before the drop out, space narrowed. In the pilot’s cradle, alone, I blinked away afterimages from the brilliant flash that preceded hyperspeed, like the universe warning me STOP in the seconds before I broke the speed limit. When I blinked those ghosts away, there was nothing through the window except black.

Not for the first time, I wished Benny had chosen a ship with a little more elbow room for the pilot. There was no space in the cockpit for anyone except me. I couldn’t see the others; couldn’t even turn around to look, because then I might miss the drop-out point; I couldn’t call out to them or talk, because then I might lose my concentration, and overshoot our stop.

They weren’t saying anything, either. Like I was alone on this ship. What had I said Hell was, again? Absence?

Nothing except darkness outside the front window. Nothing to see, no walls, no floor, no ceiling. But I could feel it, the space narrowing in on me like the sod walls of some grave, claustrophobia choking me. I was alone—

The drop-out point. I switched engines and space widened out the window, blooming bright and brilliant. I controlled our drop-out, swinging around, adjusting artificial gravity, and when our speed had slowed enough that light had caught up to us, I looked out that cockpit window and saw a marvel.

We had come out not far from the salvage ship, because I was an amazing pilot whose skills were only matched by his good looks and also I’d received very precise coordinates for this salvage. The salvage ship’s ancient, pitted metal revolved before us with slow majesty in the blazing firelight of the bloated nearby star.

A star that was verging on supernova.

It was a shame I was the only one who could see it, due to the aforementioned cramped conditions. I let out my breath and said, “That spaceship really doesn’t have a name?”

Nothing but the creaking of stabilizing straps answered me. I craned my head back until I could see the other three in the little room, Benny with his eyes shut and head tipped back against the wall, Quint with her little hands gone white around her stabilizing strap, and Leah with legs braced and gun disassembled, cleaning the pieces on the bench between her thighs.

“Hey,” I said, “what’s the ship’s name?”

“It doesn’t have one,” Quint said.

“Really?” I turned back to look back out the front window; it was time to accelerate the Viper to match the salvage ship’s revolution so that we wouldn’t crash into spinning metal and be shredded like cheese on a grater. “It must have had a name once. Everything important has a name.”

The Viper jolted and, yeah, I’d changed our theta direction a little too fast, but flying a ship was like speaking a foreign language. There were all these strict rules to follow to get the grammar right, but so long as you had the gist of it intact, you could make it up on the fly and be pretty well understood.

“I knew a girl who adopted a rock once,” I said. “She drew little eyes on it. Do you know what she named it?”

“What did she name it?” Leah asked, her tone anticipating the punchline like a mortar shell.

“Roxanne.”

“Would you please shut up about names and pay attention to landing the ship?” Quint said.

Making contact with a salvage ship was the most dangerous part of getting salvage—if I was going a little too slow, or a little too fast, we wouldn’t latch: we’d bounce, and bounciness in space wasn’t the harmless fun it was in a gravity well. In space, it tended to cause hull fractures, atmospheric loss, and inevitably death. I guessed that was why Quint was so nervous. She shouldn’t have been: this wasn’t like the FTL tunnel. I was flying, so I had control. And I was good at what I did.

I extended the Viper’s gripping arms, opening like a claw as we approached the nameless vessel. All I could see out of my window now was a long horizon of scarred hull, thinned and pitted by a thousand years’ sunlight and debris so that, in places, I could see straight through to the struts and bones. An old and mighty thing. It had been abandoned for a thousand years; no one alive might remember, but this ship must have had a name.

“I’m going to call it the Nameless,” I decided.

“Call it what it is?” Leah asked.

The Viper was close enough now. With a quick command typed into the screen, I closed the gripping arms. They slammed shut, impacts reverberating through the ship as they connected. Success.

“That’s what names are,” I said, while I ran the program that would heat up the connection and open the far side ship’s airlock. “Or what they were, anyway. We—humans, I mean—use a specific set of words as names and names only, taken from the old language. Like Benny or Quint or Leah or Sean.” We could just punch through the Nameless’s hull with the Viper’s docking chute, but when there was an airlock in existence, it was easier to use it. “But originally, names were just descriptions, like Pretty, or Willow, or—”

“Sean,” Benny said, “shut up.”

The Viper was no longer rocking about. I shut its engines off. When I turned around, I found the three of them were gathering up their things, heading for the circular aperture in the ceiling that led to the primary airlock. Benny already stood beneath it, tapping something into the wall computer, handbrace glinting. Benny was an inventor. Necessity was the mother of invention and all that, and he and I had grown up in exile from an occupied homeworld, without supplies or the money to buy anything, so he’d learned the skills to make everything. His one-of-a-kind handbrace was one of his inventions—it contained a small-caliber, single-shot projectile weapon to be used as a last-ditch self-defense.

“Air at close to atmospheric pressure, sufficient oxygen, safe temperature range,” Benny read. “We won’t need the suits.”

He pressed a button, and I heard the airlock aperture hiss open. The air of the two ships began to mix, the breath of the Namelessdisturbed for the first time in a thousand years. Then Benny, my oldest friend, the closest thing I had to family, and the last of my hometown left alive, stepped onto the ladder in the wall. His heels vanished as he climbed up and out.

Quint was next up the ladder, but she took a long time about it, her face pale as she stared up into the darkness of the other ship. Sympathy panged through me at the sight of her silent fear. Of all of us, I should feel sorry for her the least. But I knew what it was like to be frightened and alone.

“It probably won’t bite,” I reassured her. “In my experience, spaceships don’t. Not usually.”

Quint gave me a look like she thought maybe the factory had assembled me wrong, and climbed up after Benny.

“How the hell did someone like you end up here with us, anyway?” Leah asked me, but not in a way that cared. She followed Quint up and out.

That left me alone. The Viper was coffin-quiet, like it had been abandoned as surely as the Nameless had. I hurried after the others.

Frost limned the rungs of the ladder where they joined at the seam of the Nameless’s hull, exposed to the vacuum for hundreds of years and cooled almost to absolute zero before the Viper had come along and heated it up by a couple hundred degrees Kelvin. I climbed through the cold and emerged out of the floor and into dim red light. One wall of the room was a floor-to-ceiling window—or it had been, before age and decay had filmed the window over. The result was a semi-opaque piece of plastic through which nothing could be seen except the diffuse firelight of the dying star that the Nameless orbited.

That was the only light in the room. The Nameless’s computers might be—partly—functional, but the lights had burned out long, long ago. The room itself was long and hushed and dark and empty, like the antechamber to a tomb. The walls were splotched and crumbling, decay creeping dust through the flaws in their build. I coughed.

“Remember,” Quint said loudly as I emerged, “we have only a week before the sun goes nova, and we have to search this whole ship first. Our boss will let you take whatever you find on the way, but we have to find the data.”

Or else consequences, terrible consequences, fatal consequences, etc. We knew the score, Quint. I ignored her, scanning the room for anything useful, and my flashlight beam fell upon something carved into the far wall.

I hurried to the wall and fell to my knees, running my fingers over the uneven, ancient scratchings in the metal. I knew that they were letters, though they were not written in the script that I had learned as a child, nor was it written in any of the languages anyone spoke now—not my native tongue, Kystrene, or the Sister Standard that was the only language I regularly spoke anymore. This language was gone, dead, had been dead for a thousand years: Ameng. Real Ameng, right here in front of me.

I trailed my fingers over the letters, carved here a thousand years ago by someone whose dust I was probably now breathing in. A message undisturbed for a millennium until I’d come along, like it had been left specifically for me. I felt out the letters, pieced together the words.

IT IS TRUE

Something scraped to my right, probably Benny or Leah, trying to pry salvageable metal out of the decay. I bent closer to the wall and those long-forgotten letters.

WE SHALL BE MONSTERS

That scraping sound grew louder.

CUT OFF FROM ALL THE WORLD

A piece of the wall fell off beside me, clanging like a cymbal as it hit the floor. The floor hit my palms hard as I fell backwards, recoiling from the clamor.

Dirty fingers reached out from within the wall, curling around the edge. The nails were cracked and yellow. A head of thick, dark hair emerged, the locks trailing over shoulders and down the side of the wall.

The creature from inside the ship flipped out onto the floor and rose to her feet, shaking wild hair out of her face. It was a woman, the bones of her face standing out sharply, pale brown eyes large in her hungry face.

All movement in the room ceased. We stared at her as she stared at us, with just as much surprise.

Then she dropped her head back and screamed.

CHAPTER TWO:THREE CONVICTS AND A GENEROUS OPPORTUNITY

Let me be clear: that ship should have been empty. If that hadn’t been the case, we would’ve never been sent there.

A week before a ghost-woman screamed at me on an abandoned spacecraft, some men in suits arrived near midnight to take me from my cell. I didn’t think the Republican authorities on the planet Parnasse were prone to ‘disappearing’ illegal refugees who were accidental thieves and repentant almost-murderers, but it wasn’t totally outside the bounds of possibility. Still, I’ve spent a lot of my life being hauled around by authority figures, so I’ve learned when kicking up a fuss won’t do me any good. I followed them onto some cargo elevator that stopped between floors and emptied out into a hallway without cameras. This was the most interesting thing that had happened since the take-down a week ago, which had been full of police officers shouting orders in Sister Standard so tersely and with such heavy Republican accents that I’d almost had trouble understanding them. The guns pointed at my head and Benny’s had made their meaning clear enough, in the end.

“Where’s Benny?” I asked as we started down the hallway. I got no response.

Maybe they couldn’t speak, or couldn’t understand. I tried my question in Kystrene, and Illenich, and Patrene, and once in what I was pretty sure was the local dialect of sign language, but they gave no sign of understanding, which meant they were probably just ignoring me. Fine, I was used to being ignored. Only a handful of Kystrene had escaped the subjugation of our homeworld, and promptly been absorbed by a Republic that preferred pretending nothing had ever happened to facing the fact that they’d abandoned our planet to its fate. Averted eyes and shut doors were commonplace; a little feigned blindness wasn’t about to stop me.

My escorts paused in front of a closed door. It was a perfectly ordinary door, like every other door in the camera-less hallway, but I had some reservations about opening it.

“Did you know there are dialects of sign language?” I asked my escorts, staring at the handle for that door. “There’s a standardized version, thanks to the Ministers, but it varies by region anyway. Visual languages follow the same rules as spoken ones—”

One of my escorts turned the handle, opened the door, and shoved me inside. I stumbled into a well-appointed room. And standing in the corner was—

“Benny.”

He toyed with the standard hospital-issue hand brace that had replaced his weaponized homemade one, but when he heard my voice he looked up and his lips went thin. Such a look. It stopped me like a brick wall.

There were two other people in the finely-appointed room with us, both strangers to me. The woman sitting backwards on one of the fine leather chairs was wearing the same rough prison clothing as me and Benny. She looked like a dirty knife thrown in with the silver. I liked her immediately. Later, I would learn that her name was Leah.

The other woman was skinny, with a short, fussy haircut. She stood behind a polished wooden desk, beneath blacked-out windows, arms crossed over her narrow chest so that her tailored jacket buckled under the arms. Her name, as I would learn, was Quint.

The three of them had arranged themselves according to the fundamental law of mob bosses meeting for a parlay: each of them with their back to a different wall. Thoughtfully, they’d left the fourth wall—the one with the door— open for me.

There was a chair in front of Quint’s desk, near the dead center of the room. I shuffled over to that chair and sat down on its generous leather cushions.

Quint eyed me down the line of her narrow nose, then said, “The three of you have committed very serious crimes. Murder,” and for a heart-stopping moment I thought that meant the boy had died, but she nodded at Leah when she said it, “or attempted murder of a very important personage,” and this time she glanced at Benny and me.

So I wasn’t a murderer. Not now, not ever. I exhaled relief and glanced at Benny, only to find he wasn’t looking at me.

“We haven’t committed anything.” Leah dug her fingernails into the fine leather back of her chair like she intended to split it. “Haven’t been to trial yet.”

“But you’ll be convicted,” Quint said. “The evidence against all of you is overwhelming. After your convictions, you’ll be given a choice: life in prison, or sentence commutation through voluntary military service.”

So, life in prison or a violent death at the hands of the Ministers on some isolated planetoid. And they said the Republic had eliminated the death penalty. ‘Voluntary.’

There was an antique clock on Quint’s desk, shiny bronze and ticking audibly and altogether better to contemplate than imagining facing down the Ministers again. I picked it up to hide the way my hands shook.

“This isn’t some corrupt Minister court in Maria Nova.” Leah’s voice was clipped. “Talk to our lawyers.”

“Benny and I are stateless citizens. I’m not even sure we get lawyers,” I said, and flipped the clock over to examine the back rather than see the way Benny was looking at me. I didn’t think I’d ever seen him this mad before.

“My boss is offering you a third option,” Quint said. “A full pardon. For all of your crimes.”

A full pardon? Not just commute the charges, minimize them, whatever weasel-word way of saying they didn’t plan on doing anything, but actually wipe them clean? I could get my translation jobs back without having to bolt every time the police rounded the corner. I could travel again, seek out strange new verbs and look for a place that might feel, in some indefinable and wordless way, like it could be home.

Bullshit. The past didn’t just go away, and I didn’t want to meet anyone who believed it could.

“Who’s your boss?” I asked, at the same time as Leah demanded, “What’s the catch?”

“There’s an abandoned ship orbiting a star near the end of its lifespan. Our estimates say the star will go nova within the month, likely within the next two weeks. My boss wishes you to retrieve a piece of data from the ship before the supernova destroys it.”

A simple enough task. Simple enough, in fact, that I couldn’t see the need for three felons and a secret room with no electronics. The antique clock was weighty in my lap, ticking away. I got my nails between the seam of body and back panel and started to pry the clock open.

“All three of you have experience with salvage and… avoiding customs,” Quint said, eying me while I disassembled the furniture. “My boss requires competence and discretion.”

The inside of the clock was all intermeshed wheels, mysteriously interlocked, ticking steadily. “Why does your boss need us to be discreet?”

“The data is of a sensitive nature.”

I pulled one of the gears free. “And who is your boss that he wants sensitive data and discretion?”

“My boss’s name doesn’t matter. What matters is that he’s in a position to help you.”

“Where is this dying star?” Leah asked. “If we’re stealing something, we’ll end up right back in jail. And,” she pointed one finger at Quint like the muzzle of a gun, “there’s no way we’re going to Maria Nova to steal anything from the Ministers.”

“A prison cell sounds better than the Ministers,” I agreed. So did splinters beneath the nails and any other variety of tortures. The gears I’d taken from the clock carved bright lines of pain against my palm.

“The ship is in unclaimed space, and no one but my boss knows its location. You will be the only salvagers there.”

“What exactly do you want us to steal?” I asked.

“Data. More information will be provided to you on your departure, as well as a ship and necessary supplies.”

Leah scoffed. “You don’t know what supplies we need.”

“You can choose them yourself,” Quint said. “Your budget is generous.”

“We would need a fast ship.” I’d pulled a handful of smaller gears from the back of the clock, and it was starting to look a little empty. “If this supernova is in unclaimed space and we have fourteen days or less to explore the ship before the star explodes, we’ll need to get there within a few hours. That means cutting-edge FTL.” I upturned my handful of gears onto the desk. They fell, glittering and ringing like coins.

Faster-than-light engines, or FTL, and its sister technology of artificial gravity were relatively new inventions, barely a century old. The tech was commonly available in the Republic, where it had been invented, and it was constantly being improved as part of the arms race between the two Sister Systems. No one knew if FTL was a common technology in the other Sister System, Maria Nova. The Ministers—the deadly alien race that had appeared out of nowhere, subjugated humanity for hundreds of years, and still ruled humanity in the Maria Nova system—kept information about Maria Nova strictly controlled. All we knew was that the Ministers themselves used FTL tech.

Of course, the fastest, newest ships were the most expensive. The price of the most advanced ships could be greater than the total monetary value of an outer colony like my home planet, Kystrom, had been.

“You’ll have whatever you need,” Quint said.

The clock in my hand was missing too many pieces to tick anymore, and so the silence in the room was absolute. Quint crossed her arms over her chest, but didn’t take back her word.

I exchanged a glance with Leah. Benny still avoided looking at me, but we’d worked together for eight years now. I didn’t need to meet his eyes to know what he was thinking. I said to Quint, “How much will you pay us?”

“Five hundred thousand terraques.”

That was the price of a ship by itself, and she’d offered it without demur.

“A star about to blow sounds dangerous,” said Leah. “Is that all you think our lives are worth?” She’d dug her nails through the leather of her chair all right, her arm draped over the back.

“One million terraques, then,” Quint said.

I tossed another gear on the table. “Personally, I don’t get out of bed for less than two.”

A slight hesitation, this time. “Done,” Quint said.

“Each.”

A longer silence, so long I thought she would refuse.

Quint said, “Deal.”

I ran my finger through the pile of gears, separating them out onto the table. How many people in the Republic had that kind of finances? Not very many. “It’s an attractive offer. How do we know your boss can pay?”

“My boss is… a significant politician in the Republic. He has the means, and the authority, to enlist your services and pay as promised.”

So Quint’s boss was a Senator. How many Senators did the Republic have? Twenty-five? Thirty? And how many of those Senators had this much money? I separated out a few gears from the pile: one, two, three.

“So you understand,” Quint added, “why discretion is important.”

“We understand,” I assured her, toying with those three little gears.

“Then you accept the offer?”

“I’m in,” Leah said.

Benny spoke for the first time. “So am I.”

Quint clasped her hands together. “Very good. I’ve prepared an overview of what we know of the salvage vessel, and what—”

“Wait, wait, wait.” I waved my arm over my head; my hand ended up directly in front of her face. “You never asked me.”

I saw Quint suppress a sigh. “Mr. Wren, do you accept the offer?”

I smiled at her. “No,” I said.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...