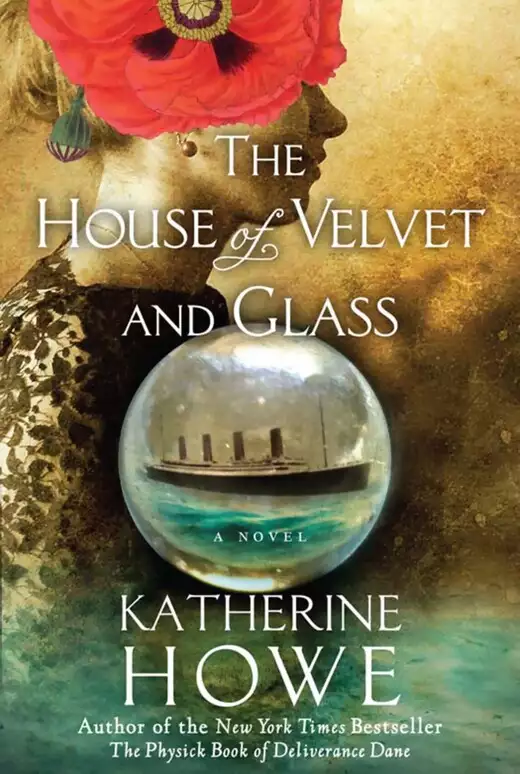

The House of Velvet and Glass

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Katherine Howe, author of the phenomenal New York Times bestseller The Physick Book of Deliverance Dane, returns with an entrancing historical novel set in Boston in 1915, where a young woman stands on the cusp of a new century, torn between loss and love, driven to seek answers in the depths of a crystal ball.

Still reeling from the deaths of her mother and sister on the Titanic, Sibyl Allston is living a life of quiet desperation with her taciturn father and scandal-plagued brother in an elegant town house in Boston's Back Bay. Trapped in a world over which she has no control, Sybil flees for solace to the parlor of a table-turning medium.

But when her brother is suddenly kicked out of Harvard under mysterious circumstances and falls under the sway of a strange young woman, Sibyl turns for help to psychology professor Benton Jones, despite the unspoken tensions of their shared past. As Benton and Sibyl work together to solve a harrowing mystery, their long-simmering spark flares to life, and they realize that there may be something even more magical between them than a medium's scrying glass.

From the opium dens of Boston's Chinatown to the opulent salons of high society, from the back alleys of colonial Shanghai to the decks of the Titanic, The House of Velvet and Glass weaves together meticulous period detail, intoxicating romance, and a final shocking twist in a breathtaking novel that will thrill readers.

Bonus features in the eBook: Katherine Howe's essay on scrying; Boston Daily Globe article on the Titanic from April 15, 1912; and a Reading Group Guide and Q&A with the author, Katherine Howe.

Release date: April 10, 2012

Publisher: Hachette Books

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The House of Velvet and Glass

Katherine Howe

North Atlantic OceanOutward BoundApril 14, 1912

Somewhere below the hubbub of the dinner hour, under the omnipresent vibrating of the ship’s engines, a clock could be heard beginning to chime. Helen Allston tightened her grip on her daughter’s elbow, brushing aside the lace from Eulah’s sleeve to better settle her fingers in its crook. She cast a sidelong glance at Eulah, whose buoyant anticipation seemed not to register her mother’s weight on her arm. Eulah’s face, flushed and pink, eyelids darkened with such a cunning hand that even Helen, who knew better, found the change difficult to detect, wore a bright, open expression that few other women’s daughters could manage with success. Helen sighed with satisfaction. She never tired of seeing the world through Eulah’s eyes, young and willing as they were.

But not too willing, of course.

“What a fetching way you’ve done your hair,” she murmured, steering Eulah with a firm hand toward the grand staircase. Her daughter’s blond curls, too unruly for Helen’s liking most of the time, had been twisted off her forehead and fastened back in a roll, then smothered with a cloud of fragile black netting fastened at the crown with a butterfly, its enamel wings set en tremblant, and so shimmering slightly with Eulah’s every movement.

“My brooch?” Helen said aloud, recognizing the ornament, and Eulah turned to her, eyes wide with mock innocence.

“You don’t mind, do you, Mother?” she asked, dimpling. “Nellie said that all the New York girls were wearing brooches this way, and I thought . . .”

Helen held her gaze for a moment, sufficient to indicate whose brooch this was really, but not long enough to instill any real remorse. She knew that she was inclined to give Eulah too much, rather than too little, leeway. Eulah had a way of making one see the absolute logic of her preferences, no matter how unorthodox. And she had to admit that the new maid they’d brought with them had a good eye for what was fashionable in hairdressing.

“Well,” she demurred, and Eulah laughed, placing her hand on her mother’s, knowing the battle was won before it started.

“Just remember, my dear, that for all that New York fashion, you’re a Boston girl,” Helen whispered, to Eulah’s puff of exasperation. This motherly remonstration dispensed with, the two Allston women paused at the top of the staircase, readying themselves.

Helen’s gaze traveled over her daughter for a final appraisal, wanting to ensure that everything was in its place before they swept down the stairs and into the first-class dining room. Under the netting Eulah’s liquid blue eyes glimmered with anticipation, behind which lurked something else that Helen struggled to identify. She peered closer. Determination, perhaps.

She was accustomed to seeing her youngest child determined. All her children were willful, of course, but Eulah had taken the Allston stubbornness and aimed it outward, at a world that she felt needed fixing, with the same alacrity that Helen’s two older children aimed inward, at themselves. Perhaps after all Eulah finally understood the opportunities available to her on this journey, even more than Helen had guessed.

This determination appeared in the obvious care that her daughter had taken with her evening dress. Helen took pleasure in the creativity Eulah showed in instructing the dressmakers back on Tremont Street, and she suspected that her hours with the dressmakers in Paris would only make Eulah’s directions more demanding. Well, she supposed they would be, anyway, given all that time poring over Journal des Dames et des Modes.

Helen thought it best that Eulah not attempt to look too French, at least not until well after they returned from the tour, so she was glad to see her waist just a little high but still bound with a satin sash, a deep vermilion that she recognized from one of Eulah’s coming-out dresses last winter. The reused satin gathered a rich, narrow column of marigold silk with a matching lace overlay around the bodice, which suited her figure marvelously. Granted, the bodice was just a shade low for Helen’s taste. But she had to admit that the lower cut set off Eulah’s grandmother’s cameo beautifully. All in all, Helen concluded that the months in Italy and France had done wonders for her daughter. Eulah had left Boston a fresh, lively girl, and now she had all the freshness of before, but with the sophisticated gloss that can only be imparted by prolonged exposure to certain works of art, performances of opera, and the perfumed air of fashionable restaurants.

Helen cast a melancholy eye down at her own costume, an evening dress a few seasons out-of-date, but still serviceable. Navy taffeta, low on the shoulders, with black beadwork and sashed with pale blue. She wished she had thought to take it over to Mme. Planchette’s atelier for a sprucing up, shortening above the floor, at least. Her slippers groped around in puddles of silk, hunting for purchase on the polished deck. Helen frowned, regretting her age, and her hand sneaked up to finger the seed pearl choker nestled in the delicate skin of her throat.

Of course Eulah’s loveliness was a credit to her mother. And Helen prided herself on being remarkably well preserved. Her face had only the slightest trace of lines at the edge of her mouth, her eyes were as clear as they ever were, and she only kept the spectacles on a golden lorgnette at her waist for the reading of menus. The rinse that she used was very clever indeed—not even Eulah suspected that Helen’s rich dark hair, now heaped in an elegant pouf at her crown, was less than natural in coloring. At least the navy of her dress complemented Helen’s skin, pearlescent in the low electric light. She would have preferred gas, at least from an aesthetic standpoint, but she supposed the ship must have all the latest modern conveniences. Lan would disapprove, surely. At the thought of her husband, Helen’s face darkened but brightened again almost immediately.

“Why, if it isn’t the Misses Allston!” boomed a young man’s voice, and Helen felt a familiar hand at her elbow. She turned and met the merry face of Deke Emerson, slick haired and apple cheeked in his tight evening clothes, already flushed from his exertions in the library in the hours preceding dinner.

“Why, Deckie!” Eulah squealed, clapping her hands. “I wondered if we’d see you. Mother says that there’re quite a lot of our set on the manifest, but we haven’t seen anyone yet. Isn’t it just marvelous!”

“It is. Doubly so,” Emerson managed, with a little trouble, “now that I’ve found two such sharming dinner companions.”

Helen smiled her most tolerant smile. “My dear Mr. Emerson, what a pleasure. We would be so grateful if you would escort us into the dining room. We’ve engaged to dine with Mrs. Widener this evening.” She emphasized their dining partner’s name, and gave him a weighted look.

“Ah!” said Emerson, comprehending, with an acquiescent waggle of his eyebrows. “I approached you with no other object in mind.” He offered each woman an arm, and with a gathering of skirts and nerves, they descended the grand staircase to the dining room.

As Eulah nattered to Deckie about the wonders of motor dashes through the Bois de Boulogne and the fashions worn by Parisian women, Helen caught her breath at the glittering scene unfolding before her. The staircase itself was a marvel, more suited to a Parisian hotel than an ocean liner. It was carved out of an elegant wood—Lan would know what it was, and he would probably scoff at going to such expense on the fittings of a ship. Like most seagoing men, Lan could be pigheaded about traveling for pleasure. Well, it couldn’t be helped—Eulah must go on the tour. When he saw the change wrought in his youngest daughter, the exquisite finish that Europe had applied to her, Helen knew that Lan would agree she had been right.

The staircase was festooned with carved wooden curlicues, lit by a cherub on the central railing holding aloft an electric torch. Overhead soared an illuminated crystal dome delineated by wrought iron, which reminded Helen of the coils and leaves of the shopping arcades in the rue du Faubourg. The landing of the grand staircase featured a clock with Roman numerals and sharp hands, its face dwarfed by ornate woodwork. She gazed at the clock as they passed down the stairs; presumably the dinner chimes hailed from it. Helen frowned, confused.

“Mr. Emerson,” she said, interrupting Eulah’s enthused discourse on an opera singer whom she had spotted in a café the evening before they departed for England.

“Yes, Mrs. Allston?” her escort replied, solicitous in his pronunciation.

“Is there anything the matter with that clock that you can see?” she asked, nodding her head in its direction.

“Why, I should think not.” He laughed, matching his pace to theirs. “Ship’s brand-new, you know. What’s the word these sailor types use? Shipshape?”

Eulah giggled, digging her elbow into Emerson, and Helen’s frown deepened. The clock bothered her. It looked oddly familiar, but she couldn’t have seen its like before. And try as she might, she couldn’t quite make herself understand what time it was reading. Even this confusion felt familiar; in another moment she would be able to remember what this reminded her of. It was the most curious sensation.

Just then an elderly couple whom Helen recognized from their Tuesday evening lecture society passed by on the way upstairs to the first-class lounge, and she snapped to attention. They bowed, and she nodded, introducing her daughter and Mr. Emerson. The group joined in a few moments’ collective exclamation over the relative fineness of the ship, the dreariness of shipboard life, the delight in continually running into one’s Boston acquaintances while abroad, the miserableness of the Popish peasantry in rural Italy, and the great relief to be returning to Boston, where one could have a proper meal at last.

“Gracious, Mother, listen!” exclaimed Eulah once they had freed themselves from the elderly couple. The band had begun to play, and at the bottom of the staircase they swept through the reception hall and arrived at a splendid dining room, tables all laid with crisp white linen. Tiny candles cast the sterling tableware in warm, twinkling light, and the room was filling with murmuring clusters of people, some few couples dancing at the end of the gallery, the men in perfectly turned-out evening dress.

But the women! Helen smiled as she surveyed the flock of women illuminating each cluster of black-coated men, like tropical birds in a sea of penguins. There was Mrs. Brown, as if Helen needed any help finding her, so insistent was her bellowing western voice, her impressive girth swathed in layers of mink unfitting to April and unmistakably expensive. And there was beautiful young Mrs. Astor, the same age as Eulah, in quiet conference with Mrs. Appleton, neither of whom Helen had met, but Eulah often remarked over their doings when reading the columns in Town Topics. Mercy, how elegant Mrs. Appleton looked. Her gown was of a shell pink so delicate that it almost seemed not to exist.

The sound of humming broke in on these reflections, and Helen shot a reproving look at Eulah, the humming’s source.

“Oh, but I love this song, Mother.” Eulah smiled. “Dum dah dee dum dum duuuuum.”

“Goose,” teased Emerson as he propelled them to their table. “You can’t know this song. It’s brand-new. Why, I only just heard it in Paree, and at a café where your mother wouldn’t ever let you go.”

“I do so know it!” Eulah mock-pouted. “I can even remember some of the words.”

“Is that a fact.” Emerson smiled.

“Dum dee dah dah, hmmm hmmmm silver liiiining . . .” Eulah warbled, her gloved hand drawing musical circles in the air at her shoulder.

“Eulah!” Helen scolded. But her exhortations were cut short by their arrival at the appointed table.

“Well, ladies,” Emerson said, holding on to the back of a chair for extra support as he executed a gentlemanly bow. “Here is where I bid you adieu.”

“You’re too kind, Mr. Emerson,” Helen said, dismissing him, not unkindly.

Eulah gifted Emerson with her most celestial smile, and after he had helped them, as best he could, to their seats, he withdrew.

Helen leaned in to admonish her daughter about her conversation, when she was interrupted by the appearance of Mrs. Widener and, just behind her, a mustachioed eminence who could only be her husband, George. Helen sighed, resigned. She hoped Eulah would have better sense than to go on about her absurd political ideas in front of Mrs. Widener. For all Europe’s salutary influence, Helen worried that her daughter was still dangerously forward thinking. Helen had even caught her lecturing Lady Rutherford in the dressing room at the opera on the necessity of female suffrage.

Of course, Helen had a few unorthodox interests of her own. Not political of course. Spiritual ones, mainly. Mrs. Dee always said Helen owed it to herself—to the world—to expound about the wonderful things they were accomplishing at her Wednesday evenings. Perhaps Eulah was right and Helen oughtn’t lecture her about proselytizing. But babbling on about nonsense in one’s sewing circle was one thing, and doing it at dinner on the first real night of a transatlantic passage was something else.

“Eleanor!” Helen smiled up at her dinner companion, nudging Eulah under the table with a slipper to summon her attention. “My dear, how are you? What a long time it’s been. And Mr. Widener traveling with you. How nice.”

“Helen,” Mrs. Widener acknowledged, offering her hand, which Helen took. Mrs. Widener adjusted the ermine at her shoulders, casting a slow, calculating gaze around the dining room. Finally she sighed and sank into the seat next to Helen Allston, rearranging her skirts and settling against the gilded seat with patient assistance from her husband, who then seated himself and proceeded to drum his meaty fingertips on the tabletop. A few moments passed with the table in silence as the band continued, diners in small clusters began to pick their way to their own tables, and Helen fumbled in her mind for something more to say.

“Well,” Mrs. Widener said at length. “Here we are.” Her husband grunted in assent.

Helen smiled, leaning nearer, and began, “My dear Eleanor, but you remember my daughter Eulah, don’t you? We’re on our way home from the tour,” as Eulah trampled over her mother’s introduction with “How d’you do, Mrs. Widener! And Mr. Widener,” extending her gloved hand across the little nosegay of lilies at the center of the table.

“Of course,” Mrs. Widener allowed, clutching and releasing Eulah’s hand. Her husband followed suit.

Just then a breathless young man appeared from within the crush of people and stooped down to Mrs. Widener’s ear with a “There you are, Mother. I’ve just spent five minutes trapped at a table with Eddie Calderhead, listening to some business scheme of his. Picked up the wrong table card. Nearly had to promise him twenty thousand dollars just so’s he’d let me leave.”

“You didn’t, did you?” Mr. Widener grumbled, but his son paid him no mind.

The young man collapsed into the free chair at his mother’s side with a grin. “Nearly, I said,” he tossed off with a laugh. Mrs. Widener smiled a mother’s indulgent smile, and turned to Helen.

“And you remember my son, don’t you? Here, Harry, meet some lovely people I know from Boston. Mrs. Helen and Miss Eulah Allston.”

“How d’you do,” Harry said, rising with a nod at each, and then seating himself. Helen took in this unexpected development closely. So the Wideners had brought along their son. He was older than Eulah, to be sure, but not so very much. Twenties, thereabouts. A Harvard man, impeccably dressed. Hair a bit messy, but it gave him a sweet, bookish air. Fine jaw. Lovely, straight Roman nose. Roman, or Grecian? Oh, she could never remember. Helen wondered if he was entering into his father’s business. Trolley cars, wasn’t it? Lan would know. Of course, his mother being an Elkins, what his father did hardly mattered.

“I was just telling your mother,” Helen ventured, “that Eulah and I are returning from Paris. Her first time, you know.”

Harry’s eyes settled on Eulah with interest. “Why, that’s capital! Everyone should go to Paris at least once. Some excellent book dealers there as well. How’d you find it?”

Eulah allowed herself a small, mysterious smile, as though she were newly privy to untold mysteries at which Harry could only guess.

“Why, I suppose it was . . .” She paused, pretending to search for the perfect word, and so drawing his attention. He edged closer to hear what she might say, and Helen felt her heart flutter.

“Magical,” Eulah finished. “Just so. It was all magical. The art. The opera. The balls.”

“The ateliers,” Mr. Widener muttered to no one in particular.

“What is it that you do, Harry?” Helen dove in, rescuing the table from Eulah’s tendency to rhapsodize.

“I am a bibliophile,” he said with gravity, ignoring Mr. Widener’s audible snort.

“Are you!” Eulah exclaimed as Helen blinked in confusion.

“Indeed. We were just in Paris as well, as a matter of fact. I was there seeing if I could hunt down this particular volume, and Mother and Father decided they would come along for a change of scene.”

“Paris!” Eulah cried. “How funny we didn’t see you any sooner. I wish you’d tell me about the book you were looking for. I just love books, you know. Did you find it?”

“It’s called Le Sang de Morphée,” Harry said, rising. “And I will tell you everything there is to know about it, if you’ll only dance with me.”

Mrs. Widener suppressed a startled cough as Eulah turned her delighted eyes to Helen. “May I?” she asked, already halfway to her feet, Harry reaching, too late, to pull back her chair.

“Why, of course, my dear!” Helen beamed. “You needn’t bother about us. Catch them while they’re still playing that song you like.”

Giggling, Eulah placed her hand into Harry’s and allowed him to help her away from the table, the music seeming to swell in concert with Eulah’s growing pleasure. Harry supported her back with a firm hand and, executing a few masterly steps, waltzed them away into the throng of dancers at the end of the gallery.

Helen sighed, pleased, thinking of the cotillion when she first saw Lan. She had felt so grown up, in the stiff silk evening dress her mother ordered, her hair put up for the first time. Helen noticed him right away, even before her mother pointed him out, whispering his marriageable qualifications in her ear with irritating urgency. Helen hadn’t heard a thing her mother said. Perhaps his being so much older was a part of it: his face was nut brown, and his eyes looked haunted and knowing. All those years at sea, and it seemed that part of him was forever at sea, unreachable. She shivered at the memory.

Harry Widener might not be as mysterious to Eulah as Lan had been to her, but then Eulah didn’t have Helen’s taste for mystery. Mrs. Dee had recognized the spark of the unusual in Helen right away, but it was a private spark, one that she kept hidden beneath a well-rehearsed public face.

Eulah, however, was an outward-looking girl. Headstrong, too quick with her desires and opinions. Helen worried that she was hungry for life, almost demanding of it. She would do well with a young man like Harry: well educated, moneyed, bookish, reliable. A trifle boring. He would settle Eulah down. Helen pressed her lips together in resolve. Never mind the four thousand dollars for the ticket, then. Lan could complain about the expense as he might, but it was worth it if she could see at least one of her children settled.

“Le Sang de Morphée indeed,” Mrs. Widener remarked to herself, surveying the glittering scene before her with a gaze of supreme boredom.

“Blood from a stone, more like,” Mr. Widener replied, resettling a pair of gold spectacles on the bridge of his nose and applying his attention to a sheet of heavy card stock in his hand. Helen was shaken out of her reverie long enough to notice that menu cards had appeared. Oysters! Well, she supposed that was apt. And perhaps that boded well for Eulah’s chances. Helen placed equal stock in the power of old wives’ tales as she did in the newer branches of thought. Consommé Olga, whatever that was. Poached salmon and mousseline sauce with cucumbers.

“What is the name of this tune, Helen?” Mrs. Widener interrupted her thoughts with a poke of her gloved finger on Helen’s forearm.

“Why, I’m sure I don’t know.” Helen smiled, catching a glimpse of Eulah in the crowd of dancers, her head thrown back in exquisite laughter at something Harry was saying. Through the rising babble of dinner conversation, the clinking of cutlery and glassware, the swelling horn section of the band, Helen wondered if she could be hearing the clock tolling again. Was it tolling in actuality, or just in the back of her mind? She pushed the question aside, taking up the menu again to see what gustatory delights lay in store for her and her daughter.

Roast duckling in applesauce. Parmentier and boiled new potatoes. Cold asparagus vinaigrette. Pâté de foie gras, and—oh, Eulah would be so pleased—chocolate and vanilla eclairs! Helen turned in her seat, searching for her daughter’s gay face in the crowd of revelers, dropping the menu in her haste on the floor, where it settled against the gilded leg of her chair.

At the top of the menu, engraved in elegant, nautical letters, was written the name of the splendid ocean liner that was carrying them home: TITANIC.

Chapter One

Beacon HillBoston, MassachusettsApril 15, 1915

Goodness, but the air was cloying. Sibyl Allston felt a cough rise in her chest and pressed her handkerchief to her lips to silence it. Thankfully she had soaked the kerchief in a little 4711 this time; the astringent, citrusy scent of the cologne sharpened her mind and pushed away the room’s miasma. She shifted, feeling her heart turn over in her chest, lurching in trepidation tinted with a strange kind of excitement.

Across the table, Sibyl observed an anonymous man, on the elderly side of middle age, also overcome by the heavy atmosphere. His eyes watered, and skin hung in sallow folds over his detachable collar. She didn’t know his name, though she supposed it would have been easy to deduce from the papers if she bothered to look. Sibyl saw him, every once in a rare while, driving down Beacon Street in an old-fashioned brougham, one of the last ones in town, his eyes sheathed in worry. Strange that they should always see each other here, always be seated directly opposite one another, and yet never breathe a word.

Mrs. Dee insisted on that. Absolute secrecy, and absolute silence. Mrs. Dee had a way of dealing only in absolutes that Sibyl had once found reassuring.

The parlor where they gathered every year had been redone in the modern style some decades ago, in homage to Mrs. Dee’s “celebrated” status. The furniture was all carved rococo woods, weighted down with curlicues and waxen fruit and snarling animal faces, the seats upholstered in scarlet silk with golden tassels. The walls bore silk upholstery in a rival shade of magenta patterned with rosebuds, their dignity screened from sunlight by double-hung velvet portieres in deep navy, kissed by sun bleaching at their fringed edges, ends puddling on the floor. The fireplace mantel was black marble, crowded with daguerreotypes and small geodes clustered on a doily, with twin crystal whale-oil lamps at either end.

The mantel also held a small brass dish, shaped like a leaf, with a smoldering cake of incense, its smoke snaking upward to the ceiling. Two ochre Turkish rugs warred for prominence over the floor, rivaled only by the vitrine against the far wall, cluttered with porcelain, bronze sculptures of frolicking nymphs, and glass-eyed stuffed birds frozen in flight. At the center of the riot of objects, each coated in a dignified veil of dust, glowed a glasslike orb nested in velvet. Sibyl eyed this item idly, attracted to its cleanness, she supposed, for it alone seemed to bear the trace of polish and care.

Sibyl herself sat perched on a hassock that positioned her too low relative to the table in the center of the room, her knees drawn up and angled sideways, one hand clasping the opposite wrist. A slender woman, ebony eyed and dark browed, with a long nose and milky skin, Sibyl dressed practically, in shirtwaist and slim dove gray skirt, her hair gathered in a bun at the crown of her head. Her one concession to adornment was a small pin at her throat, of gold and black enamel encircling an ivory wafer patterned with two laurel leaves. The laurel leaves were so cunningly worked that it was almost impossible to tell that they were formed from pale human hair: Helen’s mother’s. Helen herself had worn the laurel leaves for years; it was a wonder the pin hadn’t made the voyage with her. Sibyl reached up to finger it, reassuring herself.

The pin was an outdated ornament, but Sibyl herself was outdated in some respects. Not that she really minded anymore. At twenty-seven she had finally accepted that her life would remain confined to the oversight of her father’s household. She clasped her hands in her lap, digging a thumbnail into the flesh of her palm to distract her from the sore spots forming under the bones of her corset. Maybe Eulah had been right about rational dress after all. She shifted her weight, stomach sinking at the thought of her sister. The waiting was the worst part. Soon they would begin.

“If you would all kindly take your seats,” Mrs. Dee intoned from the parlor door, where she had appeared with no warning.

The celebrated medium enjoyed making an entrance though sometimes found it difficult, given her small stature. Sibyl appreciated that Mrs. Dee was always the last one in the room, counting on the element of anticipation and surprise to make up for what she lacked in intrinsic majesty. Plump and mono-bosomed, waddling in last year’s hobble skirt, Mrs. Dee waved her hands in a herding motion to gather her supplicants around the mahogany dining table. A silent butler drew back the most ornate of the various chairs, a pointed Gothic monstrosity that had been raised on casters to make Mrs. Dee seem taller. She settled herself in her throne as the dozen Bostonians in her parlor picked their way to seats that belonged to them by force of habit.

Sibyl knew a few of them; some she had known from before, in the little world of Boston society with its tight web of marriages and cousinships. Mr. Brown she knew from Belmont: she’d been to dancing school with his niece. Mrs. Futrelle, in from Scituate, her grief making her sharp features more drawn and ethereal with each passing year. Mrs. Hilliard had been in the same Thursday evening lecture club as Helen. The two Miss Newells, survivors both of the gruesome ordeal, the elder of whom, Madeleine, had been in Sibyl’s sewing circle. They were put in a lifeboat by their father on that dreadful night, never to see him again.

Not in this life, anyway.

Sibyl shivered, an inward chill raising goose bumps on her arms.

The others, like the sallow man seated across the table, remained a mystery. She knew that she might see them here and there, glimpsed in a church pew, or in a distant row at the Colonial Society; might even see one of their pictures in the Evening Transcript. No acknowledgment would be made on either side. What happened in Mrs. Dee’s parlor every April fifteenth was for them, and them alone.

“The lights, please,” Mrs. Dee commanded the butler, who obligingly turned down the gas in the overhead chandelier as he withdrew. When he slid the pocket doors to the parlor closed, the room sank into an eerie twilight. Sibyl could just make out the faint outlines of the people gathered about the table, and the shadows of the stuffed birds frozen in the vitrine. The rest of the room was murky and black, the smell of the incense almost overpowering. Her heartbeat quickened.

“Let us join hands,” Mrs. Dee’s voice suggested, swimming out of the darkness. Sibyl placed her two hands outward, palms up, on the cool tabletop, and felt unseen hands grasp them, warm and reassuring. She always found holding the hands strangely troubling, as though she were both tethered to the earth, yet isolated in the void. It felt almost obscene, this pressing of flesh, intimate, yet anonymous. As these uncomfortable thoughts passed through her mind, one of the hands offered an unsolicited squeeze.

“Now,” Mrs. Dee’s voice continued, distant and placeless. “I would like each of you to inhale deeply.” She paused. “And then exhale. And as you feel the air travel out of your body, I want you to relax.”

Sibyl did as the voice suggested, drawing the turgid air into her lungs as deeply as she could, and then letting it back out through her nose. As she did so, she felt her scalp begin to tingle, the skin loosening, just as it did when she unpinned her hair after a long day. She breathed in again, more softly, and as she exhaled the close atmosphere of the room receded, and the tingling deepened. Her head nodded forward.

“Very good,” soothed the voice, sounding farther away. “Now I would like all of you to clear your minds completely. Wipe them as blank as a chalkboard at the end of a day of tedious lessons.”

Sibyl closed her eyes, picturing her mind as the voice suggested. She wiped once, twice, three times. Then the board was empty, and Sibyl exhaled with relief.

“Now,” the voice suggested, far at the outer rims of Sibyl’s consciousness, “I would like you to focus your attention on the face of the person you would most like to reach.”

Sibyl concentrated, trying to recall Helen’s face. Her mother, looking younger than her years, though a little jowly. But Sibyl had trouble getting the details right. Her mother’s hair, for instance: how had she been wearing it? Sibyl could remember the high pinned curls that Helen wore when Sibyl was small, but she must have changed it half a dozen times since then. Had she started to gray, or was she still dark? What color had Helen’s eyes been? Hazel? Sibyl knew they hadn’t been brown, like her own. Had they been blue, like Eulah’s? Sibyl frowned, mouth pulled down in guilt. As Sibyl had grown, she found herself less willing to look Helen in the face. Her mother lingered in her memory as a voice of disapproval from the corner of the room, no longer attached to a living, expressive face.

For some reason Eulah left a more vibrant image in Sibyl’s mind. She’d been so like Helen, in her unconventional opinions and her affection for fine things, making the two women overlap in Sibyl’s memory. But Eulah, young, vibrant, suffered none of Helen’s worried disappointment. Sibyl had no trouble recalling her sister’s liquid blue eyes, the dimples in her cheeks when she said something daring, even the way that Eulah’s wild curls could be tamed into an elegant sweep up the back of her head. She could still hear the timbre of Eulah’s voice, lower and more earnest than her looks implied. When Sibyl tried to picture Helen, Eulah invariably got in the way. But that was how it was when they were alive, too: Eulah had always gotten in the way. Sibyl had only been out four seasons when their mother gave her up as a lost cause and started plotting Eulah’s entree into society instead. Eulah, who wouldn’t squander her opportunities, as Sibyl had.

“Try to see every contour of the person’s face,” the voice interrupted. “The eyes. The nose. The texture of the skin. The hair. Hold your loved one’s face before you as if you were sitting right across from him, in this very room.”

Sibyl heard murmurs of grief and recognition escape from various ends of the table, and she squinted her closed eyes, trying to do as she was told. So she couldn’t picture Helen this time; no matter. She would try to reach Eulah instead. She loved her sister, as everyone had. She had as much cause to reach her as anyone. Yes, there was Eulah’s form, the general outline of her face. Her eyes. Her nose—wait. No. Her nose had been smaller. There were her dimples, and her chin. Sibyl pressed her lips together in concentration.

“Ah!” the voice breathed. “I sense that we are being joined from the beyond! Everyone, remain focused and calm. You have nothing to fear. These are your loved ones, come to share their wisdom with us.”

Sibyl tensed, worried that she hadn’t captured the right qualities of Eulah’s face. The image kept unraveling before her, pulling apart and reforming, hazy and indistinct.

“I sense a male presence in the room!” Mrs. Dee announced, and Sibyl felt secretly relieved. Now she had more time to gather her recollections together. She was afraid that she might hurt Helen or Eulah, as if they could somehow see into the hollows of her mind and perceive the imperfection of her memory. She was afraid that they would find her love inadequate and, worse, trembled to think that they might be right.

“Sir, are you there? Can you hear us?”

Three sharp raps vibrated through the wood of the table, causing the backs of Sibyl’s hands to slap against the tabletop. A woman’s voiced gasped, and Sibyl’s pulse beat in her throat.

“John!” the unseen woman cried through the darkness. “John, it must be you!”

“O unworldly spirit,” Mrs. Dee’s voice beckoned. “Can you identify yourself ? Have you come to share your visions of the great beyond with us?”

“John?” the woman broke in, too eager to wait. “Tell me it is you! Oh, how I’ve missed you, my darling!”

Three more weighty raps shook the table, and the group heaved a collective “Ooooooh” of wonder.

“Oh, I knew it must be you!” the woman burst, her voice catching in her throat. “There’s so much that I’ve wanted to tell you.”

A long pause lingered over the table, and Sibyl could sense the tension building in the two hands that clutched hers in the dark. She tightened her own grip. No matter how many times she attended the gathering, the first manifestation always shocked her.

“Speeeeeeeeak,” groaned another, different voice, something like Mrs. Dee’s, but gravelly and deep, as though the medium’s body had been transformed into something larger. The sound was placeless, seeming to come from overhead.

“Well,” the woman began, choking back sobs. “I . . . I wanted you to know that . . . that I’ve missed you terribly.” She waited, choosing her next words. The room hung in silence, waiting.

“And Josiah—you’d be so proud of him! His schoolwork goes well. He’s growing up to be such a healthy, strapping boy. So helpful to me, and to his sisters. He excels at his lessons, and . . .” The woman paused, as though suddenly aware that a roomful of strangers was listening in on her conference with her departed husband. She swallowed audibly.

“And at chess, just like you wanted. But I make sure he doesn’t while away too much time at it. It’s not good for boys to be kept too much indoors, you know.” This last comment seemed designed more for the eavesdroppers around the table than for the visiting spirit.

“Goooooooood,” groaned the mysterious voice, and the listeners all sighed, moved by this benediction from beyond.

“But, John . . . ,” the woman broke in, aware that her alloted time was drawing to an end. “I . . . I must . . .” She gasped, sniffling back her tears, and then pausing to collect herself. She drew a deep breath, and continued. “There’s something very important that I must ask you.”

Sibyl noticed a thrum of interest travel among the seekers at the table. A secret, about to be revealed. She was glad that Mrs. Dee was so adamant about anonymity.

“Asssssssskkk,” the disembodied voice groaned, and the assembly held its breath in anticipation.

“Well, since you’ve been lost to us, we’ve had some . . . ” She paused, her voice strangled with shame. “Difficulty,” she finished.

Sibyl’s heart contracted. Most of the passengers who drowned with the ocean liner had been men, of course, as they insisted that women and children be the first into the lifeboats. It was even said that the orchestra had played hymns as the ship deck tilted, to give courage to the men remaining. Boston learned of their self-sacrifice with pride, and pointed to it as a sign of the innate manliness and worth of the sons that it had lost. Less often spoken of was the effect on families left behind, so many of whom now lacked the person most able to provide income and support. For some, poverty stalked on the heels of emotional devastation.

“You needn’t worry, John. We can manage. And Carlton has been particularly keen on looking after us. He stepped in right away to ensure that no debts went unpaid, never bothering me with any of it. He’s so like you, you know, and I was grateful to have his help, that I could concentrate on the children. Josiah took it so hard, you see, and I was terribly afraid it might turn into some sort of nervous condition. And in all that time, Carlton made himself indispensable, and I came to rely on him. I don’t know why I never noticed before, but he’s grown rather devoted to me, you see. And the children are quite taken with him.” Her words tumbled out, one over the other, as if their speed would squash any objection.

“Not that anyone could ever replace you in our hearts,” she hastened to add. “Only we’ve got to think of the future, all of us. And Carlton is really nothing like the brother you knew. If you could only see him with Josiah, I know you’d understand. . . .” The woman’s voice trailed off, uncertain, wavering.

A pause lingered over the table, as if the disembodied voice were considering what it had heard. At length it sighed.

“I . . . sssssseeeeeeeee.”

“Oh!” the woman gasped, with palpable relief. “Oh, my darling, thank you! I knew you’d never object, if you only could see.” She dissolved into weeping, and Sibyl heard the sound of a nose being blown, delicately, into a handkerchief.

“Thank you,” the anonymous woman murmured through her tears. And then, more quietly, “Thank you.”

One of the hands holding Sibyl’s squeezed, as though moved by the family scene playing out before them. Sibyl hesitated, then squeezed back.

“And now,” intoned Mrs. Dee, her voice transformed back into its recognizable, if ethereal, self. “I sense the presence changing. Who is there? Who can it be? We must all concentrate very keenly. Everyone, keep your eyes closed. Hold the image of your lost loved one in your mind.”

Sibyl did so, allowing her mind to soften. The sniffles of the woman who would marry her husband’s brother faded, and she felt herself floating, comfortable and serene, aware only of Mrs. Dee’s voice. She redoubled her efforts, painting in details of Helen’s and Eulah’s faces. She thought of them, in the days before leaving for the tour. The laughter and preparations. Her own envy. Sibyl scowled. It was her duty to remember them.

“The presence is making himself felt to me,” Mrs. Dee murmured. “But he asks that all eyes stay closed. He is shy. Spirit, we will honor your request. We only yearn to help you reach us. No matter what happens, we pledge to honor you!”

A low rumbling filled the room, indistinct. Sibyl’s heartbeat quickened.

“What are you trying to say to us, spirit?” Mrs. Dee asked. “Are you sad? Could you be angry?”

Sibyl gasped and straightened in her seat. She thought the table had shifted under her hands.

“O spirit!” Mrs. Dee said, her voice rising. “We feel your anger! Your life was over too soon! We hear your anguish!”

Sibyl’s heart thudded in her chest, astonished, her mouth falling open, and she fought to keep her eyes sealed shut. For the table was pressing against the backs of her hands. A sudden lurch, and without warning one side of the table lifted itself, then fell back to the floor with a thunk. Sibyl cried out, and gasps echoed around the room. Now the other side of the table rose, carrying the séance-holders’ hands with it, then threw itself back to the floor. First one side, then the other, until the table was rocking back and forth with gusto, as though on board a ship tossed at sea. The table shook into a crescendo of fury, the clutched hands of the supplicants hopping and slapping against its surface. Then, abruptly, it stopped.

Sibyl felt her palms grown clammy with sweat. Around the table, small sighs could be heard as held breath was let go. The hands gripping Sibyl’s loosened. For a moment, silence reigned.

“We may never know whose anger we have just seen,” said Mrs. Dee, her voice steady and reassuring. “For he has gone without a further word. But we can rest assured that merely in allowing him to share his distress with us, we’ve brought comfort to a suffering soul.”

Murmurs of satisfaction encircled the table, and Sibyl shivered with the exquisite pleasure that comes from confronting fear. The table-tipping was the most substantial manifestation she had witnessed in all her years attending Mrs. Dee’s gatherings. She wondered whose spirit had visited them. But it was a man. It couldn’t have been Helen. Or Eulah. They would never have been so angry. In public, anyway.

“We have such time and energy gathered here, that I feel one more spirit yearning to commune with us. Everyone, please turn your gaze. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...