The Last Will and Testament of Ellie Frame

This is the hardest story I’ve ever had to tell. Not because I don’t have anything to say, though. And not because I don’t have anything of value to leave behind. It’s the hardest story I’ve ever had to tell because I’m the one who’s been left behind. And there’s no one my last words will find. There’s no one to read my testament and say, Ellie was my best friend. Or She helped me push my car out of a snowdrift down the road from her house that year we had a freak snowstorm in the middle of April. Or Ellie was my girlfriend, and whenever she saw me, she always kissed me first on the cheek, then on the lips, and in private, when no one else was looking, on the space between my neck and shoulder. That was Ellie Frame. Remember her? She always had a smile ready, even for people who seemed to perpetually scowl at the world.

Her.

The girl with the camera.

I think she was the editor of our yearbook.

Everyone I ever loved is gone now. Dead. Dead as dead can be.

Dead as dead can be. An expression that, only a few weeks after “the outbreak,” as my mom calls the storms that took so many lives, is open to interpretation. It turns out that dead as dead can be is different for everyone. For you. For me. For the dead. Because some of them remain very much . . . alive, even now, after they’ve lost everything: heartbeats, brain waves. The last breaths they held in their chests as they knelt in the hallways of our high school, right before the roof and the walls began to fly apart, whirling up into the sky, higher and higher. The last thoughts they held in their minds. The last words they held in their mouths, right before the world turned to fire around them.

Some people, dead or alive, simply can’t leave. They have their reasons. And no matter how much grief their presence may cause, they sit across the table from us anyway, pretending to sip at a mug of coffee. Or they stand just over there, in a dark corner, waiting for something even they don’t know they need. Some are angry, some are frustrated, some are confused, and some are sad--so, so sad. Some of them are all of these things, and nothing any one of us can say or do will put them at ease.

And this is the hardest story I’ve ever had to tell for reasons that go beyond not having anyone left to hear it. It’s hard because already I’ve made a mistake in trying to tell it. I said, Everyone I ever loved is gone now, but that isn’t completely true. My mom and dad are still with me. It’s my friends who are gone. Becca, Adrienne, Rose.

And him--Noah. The one who, whenever I saw him, I would kiss first on his bristly cheek, then on his lips, where the scent of cinnamon gum still lingered, and, when no one else was looking, on the space between his neck and shoulder, that soft and private place where no one, he said, had ever kissed him before I did.

All of them are gone now. And Newfoundland itself is barely recognizable, unless you squint at the wreckage of the place in just the right way, at just the right time of day, when the shadows of evening move closer, in order to see the ghost of what it once was.

My parents, on the other hand, are all too present. They hover with worry. I hear their concerned whispers coming from their bedroom at night, when they think I’ve fallen asleep, when they don’t realize I’m awake and holding my breath, trying not to scream, trying to figure out how to tell this story, if to no one else, then to myself. I love them, I do love them. I love them more than anything, really. So when I say that everyone I ever loved is gone now, that’s not the truth.

It just feels like it.

The last day I didn’t feel alone in the world was in the middle of May, when I could see the end of high school opening up on the horizon. The summer I envisioned would be beautiful, like a dream you’d never want to wake from. A dream of three perfect months made up of laughing with friends. And three perfect months of seemingly endless days spent in my backyard, swinging in a hammock under the trees, with Noah’s arms around me as we planned a future where he’d be driving from Ohio State to Pittsburgh every weekend to visit me for the next four years. His cheek would be pressed close to mine, close enough for him to turn and kiss me awake whenever I’d start to drift off. “No sleeping,” he’d whisper, then kiss the corner of my mouth so that I’d turn toward him, smiling, to kiss him back. “We have to stay awake to enjoy all of this before we go away.”

But life has a way of changing quickly. Something you could have never imagined just . . . happens. And when it’s over, everything you knew and loved--your friends, your neighbors, the place you call home--is taken from you.

Noah and I were standing between our cars in the school parking lot on the day that changed things forever. We were continuing an argument that had started the night before, a stupid argument, the most stupid argument in the world. But I didn’t realize it right then because we were busy arguing about Ingrid Mueller, the girl who lived across the road from Noah in a farmhouse so old, it looked like something out of Little House on the Prairie. The surrounding farmland hadn’t been used for nearly a decade, after Ingrid’s father was killed in a hunting accident when she was eight. Shot through the heart by Charles Johnson, the feed mill owner, who mistook Mr. Mueller for a deer breaking through the brush below his tree stand. Ingrid’s father hadn’t been wearing any orange safety clothing mandated by law, even though he was hunting, so Mr. Johnson wasn’t charged in his death. And for the same reason, my mom once explained to me, the insurance company wouldn’t pay out the full amount of Mr. Mueller’s policy, which meant Ingrid’s mother had to get help from the state. The people in Newfoundland pitched in, too, of course. It’s what we do for each other. Neighbors and parents of Ingrid’s school friends brought food in the days and weeks after her dad died. Sometimes, a check or a card with some money in it. “A little something to help her keep the lights on,” my dad once said. But since then Mrs. Mueller had pretty much vanished from the public eye. And if you did see her, it was when she stepped out into the daylight to collect her mail.

Ingrid was in my grade, but after her father died, it was like she became a ghost, in the innocent way we all thought about ghosts back then. She rarely spoke unless called on, seemingly able to blend into the walls if you weren’t looking at her, only to reappear in different places, right when you thought you were alone. She didn’t make eye contact, looked away from people most of the time, down at the tips of her worn-out shoes, her eyes always sliding off to one side to peer at a blank wall or a corner. Her clothes were always three years behind the trends, and she cut her own hair--badly. If she’d been a popular girl with the money to buy what everyone else was wearing, the uneven hair could have been a fashion statement, but on Ingrid it came off as just another sad detail.

Noah was her friend, maybe her only friend. That isn’t to say I wasn’t nice to her; I was always nice to Ingrid. But Noah was a real friend to her and knew her in ways that nobody else did. He helped her and her mom on a regular basis, neighborly things. Mowed their lawn in summer. Fixed broken things, if he knew how to fix them. Wobbly table legs. A light switch that had stopped working. One time, he climbed a ladder up to their old slate roof to reaffix several pieces that had come loose and slid off after the winter ice had melted.

He did other things for Ingrid, too. Things that never bothered me until he and I had been together for a while. On Sweetest Day, when everyone bought carnations and had them delivered to their crushes during homeroom, Noah always sent one to Ingrid, even if he had a girlfriend at the time. Two years ago, when he wasn’t dating anyone, he ditched homecoming to take Ingrid out to dinner at one of the restaurants where everyone ate before the dance. These displays of attention let Ingrid know someone cared about her. And though a lot of girls would have thought it meant something more, Ingrid never seemed to push Noah for anything other than the friendship they’d shared since childhood.

But after Noah and I had been dating for about six months--the longest either of us had dated anyone--Ingrid started acting strange. In the hallways between classes, she’d be drearily drifting toward her locker with her head down, watching her feet, and suddenly she’d look up to meet my eyes. She’d never smile. She’d never say hello. Not even when I said hello first, trying to spark at least some sense of friendliness between us. And during lunch, I’d sometimes look up from whatever I was eating and find her staring at me across the long expanse of the cafeteria. I never once saw Ingrid eat anything but an apple during lunch, and even as she lifted a half-bitten core to her mouth to sink her teeth into the remaining flesh, her eyes would never leave me.

“She’s weirding me out,” I told Noah after enduring several weeks of Ingrid’s newfound creepiness. We were sitting together on the couch at his house. “I think she’s mad that we’re still together.”

“Ingrid isn’t mad,” Noah said. “You’re just imagining things, Ellie.”

“No, I’m not,” I said. “I mean it. I think she’s mad we’re still together. I think she has a time limit in her head for your relationships with other girls, and ours has expired. This is the longest you’ve ever been with anyone. I think she’s trying to scare me off you.”

Noah snorted, hearing that, trying to make me feel silly, telling me I was overreacting. He slipped one arm around the small of my back to pull me closer, to kiss me, leaving the taste of his cinnamon gum on my lips. Then he pulled away again, holding me at arm’s length to say, “Ellie, I hope you don’t scare that easily.”

“I’m not afraid of her,” I said, then pursed my lips, still worried, still frustrated by his nonchalant response. “But I do feel bad, if that’s what this is about, her not wanting us to be together.”

“I’m telling you, Ellie,” Noah said, bringing one finger up to my temple to tap at it. “It’s all in your head. Ingrid isn’t like that. Ingrid’s just . . . you know . . . Ingrid. She’s quiet. And a little socially awkward.”

I brushed his tapping finger away from my face and scowled. “Why won’t you believe me?” I asked.

Noah just pretended like I hadn’t asked the question. He tried to pull me close again, to kiss away the anger in my voice. So I backed away, flailing my hands in the air to emphasize every word I said next. “I’m not making this up. I’m trying to tell you something. You’re not supposed to act like I’m a delusional idiot.”

“Look at you,” he said, laughing lightly again, smirking in a way that made me only madder. “When you go to Pitt this fall,” he said, “I bet you’re going to major in psychology, aren’t you?”

If I could breathe fire, I would have opened my mouth right then and watched him melt into a puddle in front of me. But instead, I took a deep breath and folded my arms across my chest, then looked away from him, exhausted from going around in circles. I didn’t like where this was heading. I’d never seen this side of him before--Noah didn’t blow off my feelings, ever. He wasn’t like some of the guys at school who treated their girlfriends like objects. It was one of the things I liked about him. We had things in common. Things that meant something. Things we took the time to talk about.

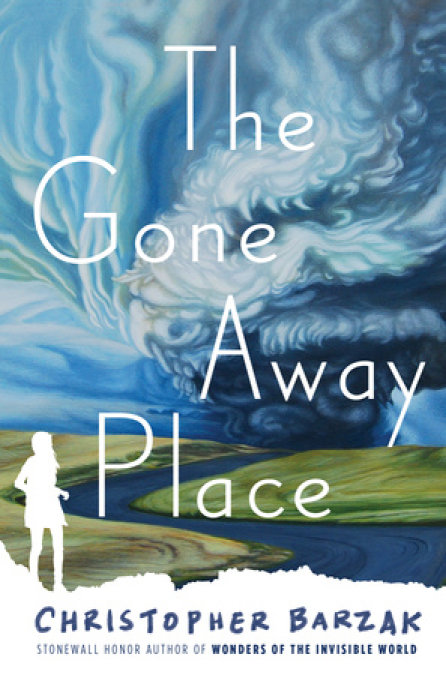

We’d gotten together in the fall when we both used our elective periods to work on the senior yearbook. And we’d talk for hours about things no one else was all that interested in: possible repeating imagery for design, the layout, the stuff other yearbooks always did that we thought was outdated. We’d talk about our vision for the yearbook, and how we were going to make a digital edition for it. We planned out a website with audio and visual content, in addition to a printed book. Something that people wouldn’t just toss into a drawer. We wanted to make something that would still speak to us after the print yearbooks had been forgotten, and we were all old and gray and could log on to the yearbook website and see ourselves and our friends as we were when we were young and fresh, just starting out.

Initially, I’d assumed Noah was nothing but the kind of guy who traveled the hallways in a pack of soccer players, the ones who take up all the space and laugh too loudly, as if they own the place. But when he took yearbook as an elective that fall, and in the first week nominated me as head editor, telling the others in class that I took the best photos for the school’s online news and always wrote interesting editorials, I had to rethink my idea of him.

I hadn’t known he’d ever even noticed me before, let alone noticed something I’d done--something I’d put my heart into, like my photography and writing. And soon I found myself starting to pay more attention to him, too. Smiling at him in the hallway. Waving at him from across the soccer field behind the school, where he and his teammates were practicing, pretending I was just taking a shortcut to the library. Asking him for his opinion on photos I’d started to take for the yearbook. We discovered we both geeked out on talking photography, the way a really good photo could reveal the essence of a person, and eventually it got to be that I couldn’t wait for my free period to see him. I knew he was feeling the same way, because he was always in the yearbook classroom before I even got there, waiting for me.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved