- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

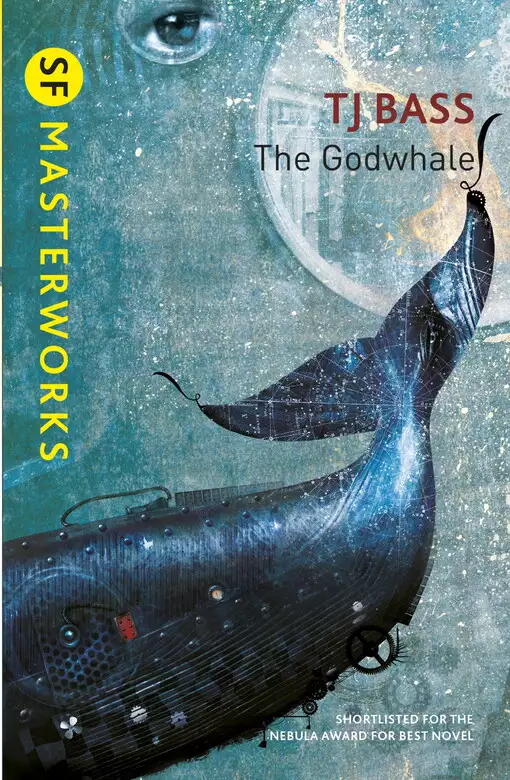

A post-apocalyptic dystopian fable by the acclaimed author of HALF PAST HUMAN, with an introduction by Ken MacLeod Rorqual Maru was a cyborg - part organic whale, part mechanised ship - and part god. She was a harvester - a vast plankton rake, now without a crop, abandoned by earth society when the seas died. So she selected an island for her grave, hoping to keep her carcass visible for salvage. Although her long ear heard nothing, she believed that man still lived in his hive. If he should ever return to the sea, she wanted to serve. She longed for the thrill of a human's bare feet touching the skin of her deck. She missed the hearty hails, the sweat and the laughter. She needed mankind. But all humans were long gone ... or were they?

Release date: March 13, 2014

Publisher: Gateway

Print pages: 302

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Godwhale

T.J. Bass

The challenge comes from two sources. One is the recognition that the repugnant future world we’re shown is a logical projection of certain trends in ours. The other is that our repugnance is given every opportunity to make itself felt. What carries us through – what makes us grimace, gulp, and read on – is the author’s skill at making us indentify with characters most of us would shudder to meet and rather die than be.

Thomas J. Bassler (1932–2011) was a medical doctor, who in the late 1960s and early 1970s wrote science fiction as T. J. Bass. He used his professional knowledge and vocabulary to remarkable effect in his novels, where physiological terms are used to describe hot feelings and sharp shocks in chill prose.

The central character of the opening chapter is Larry Dever, a vigorous young man out for a run in the park. He lives in a not-too-distant future of overcrowded cities in which this is a rare, rationed privilege. We have just come to empathise with him when, as a result of his own recklessness, he is cut in half at the waist. He has the option of suspended animation – frozen sleep – until such time as he can be repaired. He wakes after centuries to a world even more crowded, but sending out starship colonies under the direction of the artificial intelligence OLGA. Medicine has indeed advanced, but Larry finds the method offered to repair him ethically revolting – as do we. He returns to the cold sleep. Millennia later, he’s thawed again.

Then his troubles begin.

He’s soon dragging his mutilated body along for dear life through the sewers of Earth Society, the ultimate outcome of the world he was born into and the later world he glimpsed. OLGA and her star colonies are long forgotten. Humanity has been genetically modified and prenatally altered into a short-statured, short-lived species, the aptly named Nebish. Three trillion of them live in shaft cities. The entire land surface is farmed. The oceans are dead – or so everyone thinks.

Everyone is wrong. Species after species has mysteriously returned to the seas. Beyond the sky OLGA has been at work, and below it so has her remaining faithful servant, the robot whale Rorqual Maru. The remnants of the unmodified human species, which in Half Past Human haunted the Gardens as hunted scavengers, have taken to a Benthic life. When they are joined by Larry, his atavistic ally Har, and Rorqual, they become a threat to Earth Society – and an opportunity.

We follow both sides of the struggle that ensues. Without losing sight of the side we’re on, we come to identify with Hive Citizens as well as with Benthics – to say nothing of identifying with machines, some of which may well not be conscious in any human-like sense, but who charm nonetheless. In the end – but you must find that out yourself. I won’t give it away, but it leaves us with questions, one of which is whether the end of this book is indeed the end of the story the author had imagined. It seems likely that in Bass’ mind there were stories still to be told, and it’s certain that the issues so sharply raised are not in the end resolved. As Bass’ entry in the online Encyclopedia of Science Fiction concludes: ‘But he fell silent, his series incomplete.’

Why? We can only speculate, but one possibility is that the polarity Bass set up, between a humanity biologically adapted to an ever more crowded civilization and an unmodified humanity capable of surviving in the wild, can never be satisfactorily resolved. Not even interstellar colonization can offer an escape – ultimately, every successful human colony is a potential seed of another Hive.

We could, of course, decide to limit population growth, voluntarily or otherwise. Current projections suggest a levelling out of human numbers at about ten billion by mid-century, followed by a slow decline. But a declining, aging population presents its own difficulties, which in time might seem worse than the alternative. And who knows how our descendants would respond if new methods of agriculture and industrial production made room for renewed population growth without obvious inconvenience? Denying unborn generations a chance of life might – on an entirely secular ethic, leave alone religious strictures – come to be seen as wrong. And subtly adjusting people’s minds and bodies to make them happier in crowded conditions might not horrify those concerned. But then we’re on the way to becoming the Nebish, or something very like it.

The only alternative, it would seem, to this gruesome fate would be to let civilization crash and the survivors roam as savages until the next asteroid impact or ice age. This does raise ethical problems of its own, genocide being generally and (in my opinion) rightly frowned upon. The same result could happen without deliberate intent, as a by-product of nuclear war or environmental catastrophe, but again . . .

Given the parameters Bass set up, we find ourselves at an impasse. It may be that he did too, and that was why he fell silent. But that’s no reason for us to give up on the problem, or to not enjoy – with some discomfort – his blackly comic and imaginatively fertile work. As I’ve argued in the introduction to the Masterworks edition of Half Past Human, Bass’ books are very much a product of their time, but in confronting us with sharp questions about our most fundamental moral and economic assumptions they remain of pressing relevance today. They’re also, in their own grim way, great fun to read.

The doctor gave us the diagnosis, and the prognosis. He left it for us to write the prescription.

Ken MacLeod

Guillotining ruins your dayBut if you can’t be repairedIt ruins your life.

– Sage of Todd Island

Larry Dever knelt in darkness at East Gate, knees in damp gravel and hands on cold granular bars. Pre-dawn mists flattened his shock of yellow hair. Cool droplets clung to his young angular face. Jerkin and fibrejeans moist.

‘Share and update,’ murmured Larry.

‘I share,’ said his Belt, blinking an amorphous chalcogenide telltale. ‘The Park will be warm this day – ninety-two degrees – clear. Pickables: numerous.’

The long night had chilled his bones. Where was that sun? Where was warmth?

‘Sex?’

‘Probability zero point two,’ said Belt.

Larry smiled. That was probably too high, considering his youth – when gonadal activity was over 98 percent anticipatory. He rested his bony face against the bars – a Dever face that carried the heavy malar and mandibular lines of his clan. The eastern sky lightened to blue, then pale ochre, as it slowly extruded a copper solar disc that rose and drove the fog from the lake.

‘Finally.’

Optics rotated on a sentry pole. The gates squeaked open.

‘Enjoy. Enjoy. Run and spend your CBCs,’ shouted Belt. The words were accompanied by brisk music, a cavalry charge tune that warmed Larry’s blood and pulled him, running on stiff legs, into the long, dew-damp grass. Six small brown birds burst from cover and flew off. Larry raced on, disturbing leafhoppers and a squadron of yellow-grey moths. Reaching the limits of his myoglobin oxygen, he paused to catch his breath. The sun warmed the nape of his neck and dried his fibrejeans.

‘Pickables?’ asked Larry.

Belt showed him a variety of fruits and grains – huge steak-tomatoes, rich breadfruit, sticky grapes. He was dazed by the wild profusion of edible biologicals. Names? His vocabulary was limited to the city’s gelatin flavours: ambergris, calamus, kola nut, melilotus, rue, storax, and ilang-ilang.

‘Show me a flavour that is both stimulating and subtle.’

‘Genus Malus,’ suggested Belt. ‘Swim the lake and climb that far hill on your left. Look for a tree with thick gnarled branches and fruits of many colours.’

Larry ran down to the water’s edge and kicked off his woven sandals. A disturbed catfish cut a ‘V’ away from the grassy bank. Throwing his fibrejeans aside, he stepped into the cool water. Mud oozed between his toes. A chill line of gooseflesh crept up his legs and back. He tossed his jerkin back on to the grass and lowered himself into the sparkling wavelets – shuddering. Now the more purposeful cutaneous capillaries puckered to conserve heat. A stray drop choked him. His first strokes were clumsy until remotely learned cerebellar reflexes took over and he managed an eccentric rhythm – a cogwheel stroke that jerked him across the water. A spillway slide put him in the out-creek. He climbed a bridge aqueduct and rode the high stream, bodysurfing in the rushing water of the elevated waterway, high above the maze of canals and walkribbons.

The grass was soft at Malus hill. A hidden clutter of twigs bruised a sole made sensitive by the soak. Dripping, he pulled himself up into a tree and sat gingerly on the rough bark. Grafting had placed a variety of pome fruits within his reach: acid crabs, heavy reds, and light yellows. He picked a waxy red and bit into it with a juicy snap! Crisp pulp crunched noisily. Flavour! A warm checkerboard of sunlight splashed through the leaves, drying him. Fermenting windfalls attracted a noisy bee. Belt sang. Larry shifted his weight on the knobbly limb and dozed off. Dusk’s cool breeze awakened him.

‘How much have we spent?’ he asked.

Belt calculated: ‘1,207 footprints at 0.027 plus 6.11 water-minutes at 1.0 gives us 38.7 Crushing-Biota Credits.’

‘38.7 CBCs,’ mumbled Larry. ‘That much! I guess we’d better take the free way back.’ Exposing his bark-reddened hunkers, he climbed down and trotted along the inert polymer walkribbon to his heap of clothing, dressed in the sun-warmed fibres, tucking the jerkin under Belt. The cyber sputtered:

‘Did you enjoy Park’s sensory experiences?’

Larry nodded absently. Day was ending, and with it he lost Park stimuli. Returning to City-central meant monotonous, mind-dulling tedium. Pausing outside the station, he was repulsed by the sight of the crowded passenger levels with their fetid vapours. On lower levels the freight capsules waited on their rail sidings, offering a wilder but illegal ride – a temptation for new tactile thrills plus an opportunity to avoid the olfactory insults of the passenger tubeways. Climbing the protective grills, Larry ventured between dark, heavy machines reeking of aromatic lubricants.

‘Danger,’ admonished Belt.

‘Where’s your spirit of adventure? My credits will cover the trespass.’ He approached a capsule riding low on its springs – heavy. He stepped up into rungs and climbed to the catwalk. ‘Smell this tank. Must be labile calories.’ Lifting the dust cover, he set the controls on manual, wedging the cover against the toggle switch. A red light blinked. The controls slipped back to auto. He wedged the dust cover tighter.

‘Danger,’ repeated Belt.

Larry crawled along the catwalk and tugged on the hatch. It hissed open, wafting cool, spicy air into his face. The cargo was dark and refrigerated.

‘Fermenting.’ He smiled. ‘Raisins or grapes.’

‘Let’s not steal.’

‘Relax,’ coaxed Larry. His tongue was buoyed up by copious parotid secretions. ‘We won’t be caught.’ He glanced up and down the rails. The line of freight capsules stretched out of sight in both directions. He saw no guards or sentry towers so he leaned quickly inside and scooped up a handful of the moist pearls.

‘WARNING! WARNING!’

Larry’s purple, dripping hand was at his mouth when he stopped, irritated. ‘Now what?’ Belt’s amber lights changed to red. The train groaned and the capsule lurched. Larry’s wet hand slipped on the door frame. The hatch slid shut, softly but firmly, catching Larry by his waist. Belt sputtered through a bent lingual membrane.

‘Damn! Now I’ll get caught and fined for sure,’ said Larry.

The train lurched again. The dust cover fell away from the control switch. Larry felt the hatch tighten its grip. He struggled, tearing at the hatch with bloody fingernails. His stomach and liver were squeezed against his diaphragm. The air was forced out of his lungs and he found he couldn’t inhale. Belt squawked as its circuits were crushed. Larry’s tongue and eyes felt swollen. His senses clouded. The pressure on his abdomen increased as the hatch inched tighter. A narrow slit of sunlight showed his limp hands trailing in the shifting, wet mass of grapes. The click, click, click of wheels muffled as the slit narrowed further.

Darkness.

Consciousness returned. Pain had lessened. He still hung upside down, like a bat. Lips and eyelids were puffy and numb. The cargo slurped at his hands. Juices had surfaced with the vibrations – a wet flavoured quicksand that threatened to drown him. He searched for support, groping at the hatch. It was closed flush! An involuntary shudder rattled his teeth as he traced the hatch rim with moist fingers. No clearance. He wondered if the sun was still shining. There was no sensation of heat on his legs. There was no sensation at all! Not a sound penetrated the capsule’s thick walls. He listened for the wheel clicking. Nothing. Just cargo sloshing.

‘Belt!’ he wheezed. ‘Call for a White Team. I’m hurt bad. Belt? Belt?’ He palpated the crushed, funnel-shaped cyber at his waist. ‘The door killed you!’ He ran his trembling fingers over his face. ‘The door killed me too,’ he said flatly. ‘I’ve been cut in two. Damn! What a stupid thing to let happen!’

Fingers traced the edge of the hatch again and again. Unwilling to accept the loss of his pelvis and legs, he squeezed his eyes shut and tried to feel his toes. Cerebral efforts at knee bending, urination, and foot movement failed to produce any reassuring sensory feedback – only the phantom limbs of yesterday. His mind remembered the lost legs and gave him a hazy sensation of feet – cold and unreal – that refused to obey his orders.

‘Damn! Damn! Damn! I’m dead,’ he whispered.

The pop of a broken seal interrupted his premature eulogizing. Light flickered where a tank sensor squeaked out on its screw threads. The hole that appeared was located at the far end of capsule, about twenty feet away. It was large enough to admit a man’s forearm. Something fidgeted around outside of the hole and interrupted the light beams several times.

‘Help?’ said Larry, questioning whether he had found the magic word that would save him.

‘He’s alive,’ said a distant voice.

‘Let’s get him out of there,’ said another.

‘No! Wait. Please. If you open the door I’ll . . .’ His voice trailed off. His lungs seemed too small to permit both talking and breathing. He had visions of the hatch opening and releasing its grip on his severed abdomen – spilling guts and blood – and dropping him headfirst into the deep cargo of tangy, purple mush.

‘No!’

The hatch jerked open. He did not fall. In the glare of two meck light beams he saw the upraised arms of a white robot – the Medimeck – a mending octopus with clamps, haemostats, and sutures poised to stem any flood that might occur. None came. Larry hung from a tangle of circuitry – Belt had been crushed into a big clamp. The Medimeck proceeded to put in through-and-through ‘stay sutures’. Thick, white bandage-packing was pressed into the wound as the stays were tightened. Needles with wide bores were stabbed into Larry’s arms to guide flexitubes into his blood vessels. Soon he felt warm and comfortable as nutrient and sedative fluids washed through his vascular system, soothing frayed autonomics.

‘He’s stable. Let’s lift him to the stretcher.’

Larry’s detached grin faded as they buckled him into the web cradle on the Medimeck’s back. He found that he was not alone. The lower end of the cradle held a twitching bundle wrapped in a winding-sheet. The Mediteck checked the pulsing tubules attaching Larry to the life-support console. Similar tubes entered the bundle. As the teck lifted the sheet a foot kicked out, a foot clad in a woven sandal – Larry’s.

‘That’s it,’ said the teck. ‘We’ve got all of him. Let’s get back to the Clinic.’

The amphitheatre was crowded. Five colour-coded Transplant Teams were milling around the rows of seats chatting casually. Larry felt warm in his zone of the air laminar flow. Music and molecules soothed.

‘Debridgement completed. Bone Team in.’

A block of protein-sponge-matrix containing Larry’s bone dust was wired into the vertebral defect. The Vascular Team worked at a leisurely pace since the console oxygenated the detached hemitorso.

‘Is he awake?’

Larry grimaced around the large, crusted breathing tube. Mediteck glanced at the EEG patterns.

‘Encephalogram looks alert.’

‘Good. Watch for emboli. We’re going to hook up the vessels now. We’ve tried pulse irrigation, but there may still be some clots lurking in those big leg veins. Here we go.’

Flavours. A bad taste told Larry that the venous return from his legs wasn’t clear. Something had died down there and was leaking bad molecules – enzymes and myoglobin fractions. In a moment the new flavour vanished. A member of the Bone Team tested their graft for oxyhaemoglobin levels. Satisfied, he returned to his seat. Someone back in the last row began to pass food items round – snack sandwiches, sweet bars, and drinks.

‘Lost footage, ten feet. Malabsorption unlikely,’ said the captain of the Gut Team as he studied Larry’s loops of intestine through transparent sacks of wash fluid. ‘The caecum and terminal ileum are gone. So is most of the left colon. But I think we can close the gaps.’

As the repair work continued Larry dozed off several times. Most of the faces he saw were relaxed, optimistic, almost cavalier in their attitude towards their work. The only looks of concern were on the Renal and Neural Teams.

‘Only about forty grams of kidney tissue here.’

‘Same over here. He has to stay away from the Gram negative organisms. I guess we should make the Blood Scrubber unit available a couple days a week.’

‘The spinal cord looks OK, above Lumbar-two. He’ll lose a couple segments of his dermatome – somites L-three and L-four; but spreading should cover it eventually.’

Larry’s room was bright and cheerful. A wide window gave him a view of the city’s skyline through a trellis of flowers. One wall was coarse, unmatched stone with climbing vines and a noisy waterfall. The other wall was a mirror, one-way, he guessed, for anonymous observation. The wall behind his headboard was heavily telemetered. He puffed up his pillow and gazed between his numb feet towards the picture window. He smiled. Less than twenty hours after his accident, he was whole again. Skin, bones, muscles, kidneys, gut, and nerves – all sutured and beginning to knit.

‘I’m sorry to inform you that Belt didn’t make it,’ said Mahvin the Psychteck. ‘The crush was too much for the amorphous elements in his circuitry – the glasses – especially his delicate semiconductors and the chalcogenides. Belt’s personality is gone for ever.’

Larry had expected as much. ‘I don’t think I’ll be able to afford to pay—’

‘Now we mustn’t worry about that.’ Mahvin smiled, interlacing his long, soft fingers. ‘You are now classified as handicapped – temporarily, we hope – and your debts become Society’s debts. Your loan on Belt has been wiped clean. You will be given First Class Living and Rec allowances. I’ll take care of everything.’

Mahvin punctuated each sentence with an overly solicitous pat on Larry’s forearm. The words rolled around on his tongue as if they had a flavour of their own.

‘How long will I be – er – handicapped?’

‘Not long. Not long at all.’ Mahvin smiled.

‘Days? Months?’ begged Larry.

‘I’m not in Bio,’ said Mahvin sweetly. ‘Your healers have all the facts right at their fingertips. Why not ask them? I’ll be in to check on you every day. If you need anything, just fill out one of these request slips.’

‘My feet. I still can’t feel my feet,’ said Larry. The Neuro Team had been at his bedside most of the morning. Eight weeks had passed since the surgical repair, and there had been little change since the first day. A teck had placed a web of sensor wires over his numb legs and pelvis. Muscles jumped under faradic and galvanic stimulations, but he felt nothing. A lengthy printout confirmed their suspicions: spinal cord regeneration – negative.

‘Tinel’s sign is still absent,’ said the teck.

The team made more notes on their printouts.

‘My feet?’

‘I’m afraid we can’t expect much more improvement than we have right now. Ordinarily we can expect one or two millimetres a day regeneration in peripheral nerves, but your injury involved the central nervous system – and CNS tissue just doesn’t seem to heal satisfactorily. Your regenerating fibres are all caught up in the CNS scar tissue. Our tests show a ball of hyperplasic glial fibres at L-two. Nothing is getting past it.’

Larry stared at his flaccid feet – limp, white and already swollen with the fluids of inactivity.

‘But look at my dermatograms,’ pleaded Larry. ‘The skin sensation is spreading down past the scars. Why, I have four or five inches of skin with new feeling.’

‘I’m sorry, but those are peripheral nerves spreading from skin above the suture line. They usually do nicely in cases like yours. It is the cord that gives us a problem.’

‘But the surgery was a success. I’m all healed up fine. I need my nerves to walk and for bladder and bowel control. I can’t just lie here in pools of urine and faeces with all this dead meat attached to me. I’m getting bed sores already.’

‘The answer to that is a hemicorporectomy.’

‘I’m to be a paperweight?’

‘Yes. The dead meat, as you call it, can be removed.’

Larry remained depressed, silent.

‘It won’t be so bad,’ continued the Neuroteck. ‘You’ll be issued a mannequin – a cosmetic body with a companion meck personality and powerful android muscles. Ferrite converters, I think. You’ll be freed from this bed and there will be accessories for blood scrubbing. Bowel and bladder care will be automatic too. I think it will be a real improvement.’

Larry nodded. Anything would be an improvement.

The teams milled around the operating table.

‘What do we do with this part that is – left over?’

‘Why?’

‘Is he asleep?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well there’s a collector from Embryonics. They need live organs for tissue culture and budding experiments.’

‘Let them have the lower torso; just be sure it is correctly labelled in case someone orders more tests on it.’

Sixty pounds of meat and bones left the operating room, with the label ‘Larry Dever’.

Stump revision continued.

‘Cut the cord below the knob of scar tissue. Graft this bar of ilium crosswise at the base of the spine.’

The colostomy and ureterostomy openings were routed through the rectus muscles at a sharp angle so the belly muscle could act as a sphincter. Skin suture-lines were placed away from the weight-bearing points under the spine and rib cage.

Larry awoke seated in an easy chair near his picture window, a warm shawl on his lap. Only the lap was not his – nor the powerful thighs. His own head and shoulders projected from the top of a slightly oversized android – his mannequin. Larry groaned and tried to scratch his suture-line. It was cradled deep in the meck torso, behind thick chest plates.

‘Uncomfortable?’ asked the mannequin. ‘I think I have something for that.’ Soothing synthetic molecules were added to the fluids of the Blood Scrubber. Larry felt better almost immediately.

‘Thanks.’

The mannequin got to its feet slowly, gently. ‘Time to put us to bed, don’t you think?’ The sturdy legs carried him past the window. A tray of clear fluids tempted him with a variety of herbaceous distillates – floral, seedy, and fruity aromas. He sipped enough to wet his mouth, and napped.

Adapting to a mannequin was easy, physically. Larry felt clean, dry, and comfortable as the artificial kidneys worked on a blood shunt attached to his internal arteries and veins.

Psychologically, it was difficult. The tireless legs took him wherever he wished – walks, climbs, even the Long Tour. This hundred-mile foot-race toured a park strip around one of the Lesser Lakes. Contestants usually covered the course in three consecutive days of running, but Larry found it easy to do in one day. His powerful legs averaged five miles per hour, completing the tour in twenty hours. His frame was taller and bulkier now, earning respect from strangers’ eyes. Cloying females and furtive males of parasitic occupations studied him carefully now. This façade of masculine power was to make his ego even more vulnerable when the illusion had to be broken.

Rusty Stafford rubbed citrus on her skin and slept on thin bales of fresh alfalfa. Her wide-mesh body stocking accentuated her body paint as she strutted through the park strip, hunting. She saw a familiar set of cheekbones.

‘Larry! Larry Dever, you old scabbard hound.’

He broke his pace and smiled sheepishly. She ran up to him, tossing her hair from side to side. ‘I heard about your accident,’ she said. ‘I’m glad to see you on your feet again. You look great!’ Her scented hand was on his arm, guiding him towards a cluster of Dispenser benches. ‘Do you have time for a snack? Why, you’re hardly sweating at all. How many miles today?’

He shrugged off her question and offered her a seat, dialling effervescent drinks. They munched and sipped talking of their days of study at the stacks. She leaned on him, her hand on his thigh.

‘Remember what you used to call me?’ she teased.

‘I was drunk.’

‘A succulent concubine,’ she giggled.

‘You were Earl’s succulent – er – how is Earl?’

‘Gone.’ She pouted. ‘He opted for the Near Space Engineers. We untied our knot and he went out with the October convoy.’ She glanced up. ‘I guess he’s nicely settled with one of those satellite girls by now.’

Larry followed her gaze upward. ‘OLGA’s monitors . . . They do make nice wives.’

‘Mothers!’ she spat. ‘They’re so busy playing nursemaid to the entire human race that they don’t know the difference between a son and a lover. Those satellite girls are just big – big-breasted Nordics who try to mother everyone and everything. They don’t know how to treat a man after they wash him, feed him, and care for his clothes.’

Larry cleared his throat noisily and toyed with this food. She relaxed her flare and. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...