- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

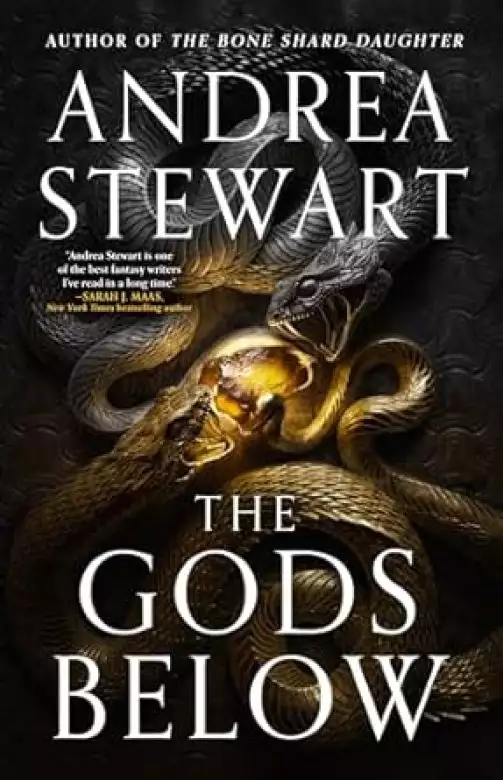

From one of the biggest new stars in epic fantasy comes a sweeping epic of warring gods, loyalty, betrayal, and a world in turmoil.

In a world ravaged by ancient magic, precious gemstones bestow magical abilities on the few individuals who are able to harness their power.

Hakara, a young woman searching for her missing sister will do anything to find her – even lead a rebellion against the gods themselves.

Full of clandestine power struggles and the battles between gods, this beginning of a new trilogy is sure to attract fans of The Bone Shard Daughter and The Poppy War.

Release date: September 3, 2024

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Gods Below

Andrea Stewart

The mortals broke the world. They took the living wood of the Numinars, feeding it to their machines to capture and use their magic. Once, the great branches reached into the sky, each tree an ecosystem for countless lives. By the time the Numinars were almost gone, the world was changed. The mortals tried, but they could not repair the damage they’d caused. As the skies filled with ash and the air grew hot, the mortal Tolemne made his way down into the depths of the world to ask a boon of the gods.

And the gods, ensconced in their hollow, in the inner sanctum of the earth, told Tolemne that the scorched land above was not their problem. The gods ignored his pleas.

All except one.

Maman lied when she told me there were ghosts in the ocean. Cold water pressed at my ears, the breath in my lungs warm and taut as a paper lantern. Shapes appeared in the murk below, towers rising out of the darkness. Strands of kelp swayed back and forth between broken stone and rotting wood with the ceaseless rhythm of breathing. There were no ghosts down here – just the pitted, pockmarked bones of a long-dead world. I forced myself to calm, to make my breath last longer.

A shark swam above, between me and the surface, its shadow passing over my face. I hovered next to a tower wall, not even letting a bubble free from my lips, my elbow hooked over the stone lip of a window. An abalone lay in my left hand, the snail curling into itself, the rocky shell of it rough against my palm. My blunt knife lay in my right. A shimmering school of small fish circled next to me, light catching their silver scales like so many scattered coins. I willed them to swim away. There was nothing interesting here. Nothing to see. Nothing to eat.

Somewhere beyond the shore, Rasha curled in our tent, silent and waiting.

The first time I went to the sea, my sister had begged me not to go. I’d held her face between my palms, wiped her tears away with my thumbs and then pressed her cheeks together until her mouth opened like a fish’s. “Glug glug,” I’d said. I’d laughed and then she’d laughed, and then I’d whisked myself to the tent flap before she could protest any further. “That’s all that’s down there. Things that are good to eat and to sell. I’ll come back. I promise.”

Always told her I’d come back, just in case she forgot.

I imagined Rasha in our tent, getting the fire going, sorting through our stash of dried and salted goods to throw together some semblance of a meal. The fishing hadn’t been good lately and now I had a snail in hand, as big as my face. I could begin to make things right if I could make it home.

If I died here, Rasha would die too. She’d have no one to defend her, to care for her. I counted the passing seconds, my heartbeat thudding in my ears, hoping the shark would swim away. My throat tightened, my chest aching. I was running out of time. I could hold my breath longer than most, but I had limits.

There was a stone ledge far beneath me – the remnants of a crumbled balcony. I had two things in hand – my abalone knife and the abalone. I needed that abalone and they were so hard to find these days. Each one would buy several days’ worth of meals. But it wasn’t worth my life. Nothing else for it. I dropped the snail and moved, slowly as I could manage, around the tower.

Its shell cracked against the ledge and the shark darted toward the sound.

I swam upward, the tautness of my chest threatening to shatter, to let the water come rushing in. The bright shimmer of the world above seemed at once close and too far. I kicked, hoping the shark was occupied with the abalone. My breath came out in short bursts when I broke the surface.

I swam for the closest rock, doing my best not to splash. Any moment, I imagined, the beast from below would shear off a leg with its bite. The water that had welcomed me only moments before now felt like a vast, unknowable thing. And then my hands were on the rock and I was hauling myself out of the water, my fingers scrabbling against slick algae and barnacles, doing my best not to shake. A close call, but not the first I’d ever had. Another diver was setting up on shore. “Shark in the ruins!” I called to him. “Best wait until it’s cleared off.”

He waved me away. “Sure. Children always think they see sharks when they’re scared.”

Did he think just because I was young that my eyes didn’t work right? Went the other way around, didn’t it? “Go on, then.” I waved at the water. “Be a big brave adult and get yourself eaten.”

He made a rude gesture at me before fastening his bag to his belt and dropping from the rocks into the water. Not the wisest decision, but he was probably just as desperate as the rest of us. I could smell the shoreline from my rock – sea life rotting under the heat of the sun, crisped seaweed, thick white bird droppings.

I wrapped my arms around my knees and watched him submerge as I breathed into my belly, calming my too-fast heartbeat. Waves lapped against the shore behind me. Early-morning light shone piss-yellow through the haze, the air smelling faintly like a campfire. Not the most auspicious start to the day, but most mornings in Kashan weren’t. My smallclothes clung to me, trickles of water tickling my skin. I’d head out again once I thought the shark had moved on. Or once it had taken a bite out of the other diver and had a nice meal. Either way, I’d slide into the water again, no matter the dangers.

I think Maman told me about ghosts in a misguided attempt to scare me. Like I was supposed to look at her, round-eyed, and avoid the ocean ever after instead of eagerly asking her if underwater ghosts ate sharks or people’s souls. Had to admit I was a bit disappointed not to find spirits lurking around the ruined city when I’d finally hauled my hungry carcass to the shore and plunged my face beneath the water. Would have had a lot of questions to ask my ancestors.

Maman wasn’t here to warn me away, and our Mimi had rid herself of that responsibility when she’d sighed out her last breath a year ago. We had no parents left. Besides, who was Maman to warn me against danger when she’d walked into the barrier between Kashan and Cressima? At least our Mimi had died through no fault of her own.

Sometimes I could hear Maman’s voice in the back of my head as I swam down, down, so far that I started free-falling into the depths.

Don’t go too far. Don’t push yourself too hard. Stay safe.

And each time that voice in my head spoke up, I stayed down a little longer, until my chest burned, until I felt I would die if I didn’t gasp in a breath. I couldn’t listen to Maman’s voice. Not with Rasha counting on me. Mimi had told me to take care of my sister. She’d not needed to say it, but I felt the weight of her last words like the press of a palm against my back.

This time of year, when the afternoon sun bore down on the water like a fire on a tea kettle, the abalone I fished for retreated deeper. They clung to the sides of the ruins, smaller ones hiding in crevices, their shells blending in with the surrounding rocks. Hints of metal and machinery lay deeper down, artifacts of the time before. All broken into unrecognizable pieces, or I’d have gone after them instead. There was always some sucker with money fascinated by our pre-Shattering civilization.

Rasha and I could eat fish, but abalone we could sell – the shells and their meat both – and children always needed things. It seemed I could get by on less and less the older I got, my fifteen-year-old frame gaunt and dry as a withered tree trunk. But Rasha was nine and I knew she needed toys, warm clothes, books, vegetables and fruits – all those little comforts she used to have when both Maman and Mimi had been alive. Every year got a little harder. More heat, more floods, more fires. Kluehnn’s devoted followers prayed for restoration to take Kashan, to remake its people and its landscape, the way it had realm after realm. It was our turn, they said.

Couldn’t say I relished the thought of being remade. I’d run if it ever came to that. I’d make for the border with Rasha and I wouldn’t look back. Kluehnn’s followers said that was a coward’s choice. I was perfectly fine with being a coward if it meant I kept my bodily self unchanged and all in one piece.

I frowned as I glanced back at the shore, rocks fading into yellowed grasses and wilting trees. There should have been more divers out by now. I might have always been first, but others usually followed quickly, jostling for the best fishing spots.

It was deserted enough that I managed to find three more abalone once I got back into the water; only one other diver made her way into the ruins. My mind picked over all the possible reasons. A fire come too close? Rasha knew what to do in case of fire. A sickness passing through camp? It had happened before. I cut my diving short and walked back to our tent barefoot, the well-worn path soft beneath my feet, the scattered remains of dried seagrass forming a cushiony surface.

Ours was not the only tent pitched near Batabyan Bay. Together with the others we formed a loose settlement. This morning, though, three flattened areas of grass lay where tents had once been pitched. They’d been there when I’d left for the ocean.

Rasha had started a fire in the pit, the musty scent of burning dung drifting toward me. A covered cast-iron pot hung over it, the lid cracked to let out steam. She ran toward me, nearly bowling me over with a hug.

I squeezed her back until she wheezed. Maybe got a bit carried away, but she didn’t complain. Her long black hair had some indefinable scent I only knew as home. Something of Maman and Mimi clung to the thick walls of our tent, permeating our clothes and our skin. I waved away the pungent smoke as I let her go, gesturing toward the empty campsites. “What happened over there?”

She shrugged. “They left just as I woke up. All three. Packed up their belongings and just hauled them out.”

I smoothed the hair from her forehead. It was quick as instinct, the way I moved to soothe away her worries. Worrying was for me, not her. “Did they leave anything behind?”

She gave me a tentative smile before holding up a comb and a horsehair doll. I held my hand out for the comb. That one had been left by mistake. Tortoiseshell, carved with the face of Lithuas, one of the dead elder gods. Her hair flowed out to the tines of the comb, which had been left smooth. I should have been excited by the find; instead, uneasiness rose like a high tide. Most people would have scoured their campsite. Most people would have taken the time to find what they’d lost. The people here weren’t rich, and the comb was a luxury, one that had passed hands from one generation to the next. No one carved the elder gods into combs anymore.

I lifted the abalone in my mesh sack. “I got something too.”

Rasha’s eyes sparkled, and her expression was a bulwark against anxiety. “Is it enough?”

I gave her a mock-startled look. “For what? What do you mean?”

She laughed before grabbing a pole to take the pot off the fire. “You know what.”

“Pretty sure you called me stupid the other day, and stupid people have terrible memories.”

“I was joking.”

“Yes, being called stupid is a very funny joke.”

“I said ‘don’t be stupid. You can’t go to the mines.’”

I mussed her hair. “Please. Same difference. Besides, if the ocean stops giving us what we need, I might be able to find work at the sinkholes. I have to consider it.”

She spooned out the porridge with the air of someone who’d come to the realization that this shitty gruel was her last meal. “No, you don’t.”

Ah, I’d ruined the mood in one fell swoop, hadn’t I? Count on me to crush delicate hopes with the clumsiness of a toddler wandering into a seabird’s nest. “We have enough, and I can dive deeper than most. Let’s not think about it. Not when we have this, eh?” I brandished the comb. “I’ll sell it at market with the abalone. And then yes, I’ll see about the garden you want.”

Wished she would answer me with a sly “So you do remember”, but she’d never been as able as I was to recover a good mood. It was a big ask. We both knew it. I could buy the seeds and we had water, but the weather was unpredictable. Crops had to grow quickly to be harvested before heat or flooding ruined them. Only thing that would make them grow more quickly was god gems, and I wasn’t going to risk the black market.

Magic wasn’t for the likes of us.

Maybe a few herbs, though. Some small greens we could carry in pots. I could do that. I dug into the porridge she’d made, putting on a show of how incredible it tasted until she smiled again. I’d once gotten drunk on fermented mare’s milk when a passing traveler had left a skin of it out after he’d gone to sleep. It felt like that, getting Rasha to smile, to laugh. But better. No pounding headache the morning after, only a soft satisfaction that for one more day, I’d mattered.

But both were fleeting feelings. When we made our way to the market, it was nearly empty. Two stalls remained.

I’d never been as attuned to the community as perhaps I should have been. Rasha and I were a unit, and I couldn’t afford to let anyone too close in case I’d misjudged them. We were young, and though my sister didn’t understand our vulnerability, I did. All it would take was two armed, halfway-skilled grown men or women, and our stash of food would be ransacked. Maybe they’d kill us both for good measure. The law didn’t mean much when you lived on the fringes. We had one another and that was enough. Or I’d thought it was enough.

I took the abalone to one of the two remaining stalls, where a woman clasped her hands together, her face rapturous. Rasha clung to the end of my shirt. I could feel the tension in her fingers, in every errant tug. It unsettled me more than it should have.

“Hey, Grandma – where’s everyone?” I plunked the abalone on her counter, though I had no idea if she wanted to buy it.

She didn’t even seem to notice. “It’s Kluehnn,” she breathed, her eyes bright.

The back of my neck prickled. I knew right then what was happening, though I still searched for a gap, for some other explanation. Restoration had been coming to realms quicker and quicker these days, but it was too soon after Cressima. I wasn’t ready. Rasha was too young, we were too small. “What, the one true god popped up out of the ground and gave everyone a holiday?”

She smiled and shook her head, wisps of white hair floating around her face like spiderwebs. “No. People have seen the black wall. It’s moving over Kashan and it’s on its way here. Everyone is setting their affairs in order. Restoration. It’s our turn.”

My heart pounded faster than it had with the shark overhead. I grabbed the abalone and Rasha’s hand. I ran.

Kashan – the Langzuan border

Everyone agrees that the Numinars were burned for their magic. That the magic was captured and used to create a lifestyle for mortals beyond our current knowledge. There are pre-Shattering relics we don’t understand – fractured items made of strange materials, paintings of cities with buildings that defy imagination, old engravings that describe magical weapons used to fight in the wars between realms.

We only had one pair of shoes as we fled the shadow wall, so I’d given them to Rasha. Dried grass and gravel crunched beneath my throbbing feet. All around us people screamed, they shouted, they lifted their voices in prayer. Rasha’s wide brown eyes looked up at mine, her nostrils flaring.

I bent and pressed my lips to her hair, knowing she couldn’t hear my whispers. “Breathe. This will all be over soon. Just breathe.” I took my own advice, the damp, smoky smell of the shadow wall filling my nostrils. The lullaby our Mimi always sang hummed in my throat, and I held Rasha’s cheek to my chest, hoping she could at least feel it. The surrounding crowd jostled, sweat beaded on brows and upper lips, the whites of eyes punctuating the sea of people – bright stars against a darkening sky. They moved like water, every so often a wave breaking against us. My body curled around Rasha’s, protecting her even as I tried to give her space for air. I risked a glance back down the hill.

A billowing black wall swept over the landscape, swallowing everything in its path. People ran ahead of it, clutching children, loved ones, belongings. One by one, they fell, they grew tired, they stopped and gave up – and restoration took them. I would not be them. I would not let Rasha be them.

Our tent was gone, the settlement we’d lived in, gone. I didn’t know what else would be gone when the restoration was complete; perhaps the entire ocean would disappear, the animals within irrevocably changed. That was what a restoration did. It made things green and lush again, but that took magic and matter. Half of the population of Kashan would be altered to suit the new landscape. Half of us would disappear, our matter used to remake our realm. The pact with Kluehnn was a two-handed bargain – one giving and one taking away.

I’d never personally agreed to it.

Stones dug into my knee as I knelt and tapped Rasha’s feet. I was the one who had to do the talking at the border, and I wouldn’t be convincing without shoes. She kicked them off. Swiftly, I pulled out the padding at the toes and strapped the shoes onto my bruised and swollen feet. Each tightening of the laces sent a jolt of pain up my legs.

I stood and pushed toward the Langzuan tents set up by the border, using my elbows and knees when the crowd didn’t give way. My sister and I were both small enough to slip through most gaps. Ahead of us, the churning, dust-filled barrier between our realms rose toward the sky, the remaining population of Kashan crushed between two insubstantial walls. The closer we drew to the tents, the more my hands shook. I didn’t have money to pay for a guide through the barrier. I wasn’t a doctor, I wasn’t a skilled artisan or anyone of note. All I had were forged papers and the desperation of a rat in a swiftly closing trap. We might still make it through to the other side, though I wasn’t sure what came next. It was easier, most days, to think only of survival. A breath held, the air aching in my lungs, the water pressing against my back as I wedged my knife beneath the abalone that I sold to keep food in my sister’s belly. All moments, all things that passed, all things that didn’t matter.

What mattered was Rasha.

A horse by the tents stamped and tossed its head. If I closed my eyes and ears, I might think it any other morning. A morning where I’d throw off my blankets, shove my feet into my shoes and rush to the shoreline before the boats disturbed the water.

There I would breathe, hearing the rasp of air in and out of my lungs as I filled my chest to its limits. And then I would slip into the chilly water, tasting salt against my lips and feeling icy wetness permeating my hair.

But I didn’t know if I’d ever swim again. We’d had to sell most of our belongings to buy forged papers, had packed the rest into small bags. The shadow wall had crept forward slowly enough that we’d been able to catch a few hours’ sleep every day. But each time we awoke it was there again, threatening to bear down on us.

“We don’t have a guide,” Rasha gasped out.

I took her by the hand, laced my fingers in hers and squeezed. “Look – we made it this far. What’s a few steps more?”

The smile she gave me was weak, but it was there, and it firmed up my heart. I wouldn’t be like Maman, whom I’d always seen as giving up. She’d walked into the barrier of her own volition, certain she could find her family in Cressima. She’d left us. Sometimes I wasn’t sure which was stronger: my grief or my anger.

There was no order here. There was not enough time for order. Ahead of us was the line for most of the refugees. To our right, a row of guards, weapons in hand, separating the riff-raff from those who’d had enough money to pay privately for escorts and guides.

Someone swathed in gray pushed past us, his voice raised. A large embroidered white eye stared at me from the back of his robe as he made his way toward the wealthy citizens. “Fleeing restoration is a weakness! Become altered or let your matter join in the effort of restoration. This is the pact we willingly made with Kluehnn. Our mortal flesh is weak! All realms will one day be altered. Will you keep running, or will you accept the blessing of the one true god?”

Someone spat at him and he ignored them. I caught a glimpse between the guards of palanquins, of bright handkerchiefs being tied over mouths. Little good some scraps of cloth would do those people when it came to the aether in the barrier, but I couldn’t blame them for trying. I could blame them for using all that money to save themselves in comfort. One of those richly carved palanquins could have bought me enough shoes for a lifetime.

And then we were close enough to the opening of the tent, a bureaucrat from Langzu hunched over the desk they’d set up there. Armed guards stood on either side of him, scale armor gleaming dully, swords drawn in a clear message: Stay back.

“I have papers!” I shouted in Langzuan, drawing them from my vest pocket. “We are legally allowed to cross!”

The bureaucrat looked at us over metal-framed glasses, his beard pinched by the press of his lips. He lifted his chin and waved us forward. A few people near us muttered curses, but I couldn’t care about anything except getting to Langzu, where nothing had yet been restored.

I slapped the papers into his hand as soon as we reached the front, Rasha’s fingers still twined in mine. She did her best to hide her bare feet. The bureaucrat looked us up and down with a skeptical gaze, and I knew what he saw. Our birth father was from Cressima, our Mimi from Kashan. Someone from Kashan might pass for Langzuan, but we never would. My heart pounded in my throat, a headache building at my temples as I forced myself to stand still, to stand taller, to look like the woman the papers had been written for.

“You are a scholar?” he said in Kashani.

Heat crept up the back of my neck. It was clear my Langzuan was not passable. “Yes,” I replied in Langzuan. “I have studied both here and in Langzu. My sister is not a scholar, but she has assisted me and also speaks both languages.” I clenched my teeth, hoping he wouldn’t test that lie. Hoping that he saw the approaching wall and knew he had to be quick.

He gave a short nod and wrote something in his ledger. “Then you’ll have the passage price.”

I felt the dry crack of my lips as I opened them, knowing this was the tipping point. We’d gotten this far. This was the last test. “I do not. We were robbed as we made our way to the border. We are both young, sir, and the people here are desperate.” As though I was not one of them. As though I hadn’t practiced these exact Langzuan phrases over and over the past few days. “But you’ll never meet anyone as willing to work as me and my sister. I can pay what I owe when we get to Langzu.”

The man sighed as though he’d heard this tale one too many times. I could feel that door closing, the opportunity slipping.

“Please,” I tried. Someone jostled me from behind and I stumbled a little to the side. Too late I realized I’d spoken in Kashani and not Langzuan. Ah, my mother tongue, betraying me at the last.

His face closed like a book. “No passage price, no passage. Next!”

I opened my mouth to protest, but the guard nearest to me took a half-step forward. I held out a hand for my forged papers, but the man only tucked them beneath his ledger. “Next!” he called again. I was floating, watching myself from some distant part of my mind, my heart a clenched claw.

“Hakara…” Rasha’s voice sounded quiet in my ears.

My feet returned to the earth as I breathed through the panic. I had to acknowledge that this way was closed to me. If I threw myself at the guards, I’d accomplish nothing except my death. I led Rasha away from the most crushing part of the crowd.

“You did your best,” she was saying, her voice smaller than even her size would suggest. “Just… hold my hand when restoration comes? I don’t want to be alone.”

“No.”

“No?” Her voice was on the edge of tears. She was trying to be strong. My sweet Rasha, who tried to mend the broken wings of birds and who’d wept when I’d slaughtered our old camel for food.

I searched the churning border wall as though I could find a gap. The aether inside whipped dust and sand into a frenzy; I could not see through to the other side. Each realm was separated from the others by these barriers, so that Kluehnn could gather enough magic to change the world in pieces. “There has to be another way. We won’t be caught here, Rasha. What if one of us doesn’t make it through restoration? What if one of us disappears?” I could live with being altered, with both of us being altered. I wasn’t sure which I dreaded more: Rasha disappearing or myself. Both sent a spike of fear through my heart.

Kluehnn’s priests told us restoration was necessary, that it was glorious. Half of us would be remade to better survive in the new landscape, in forms that held none of our mortal weaknesses. I’d heard stories of Cressima after restoration, and the landscape had gone from cold and barren to lush.

But the cost felt too dear to me and to all the other refugees gathered at the border.

Why couldn’t things just remain the same?

There wasn’t time to dwell on that. The shadow wall was moving closer, its progress inexorable. Think. I had to think. I’d failed at getting us past through the official channels. There would be other groups at the border, not just the fabulously wealthy ones. Ones who’d spent most of their money to hire their own guides, who already had something waiting for them on the other side. They’d be going through on their own. I was strong, I was quick – there had to be something I could offer.

“Come on.” I tugged at Rasha’s hand and we left the tents of Langzu behind. People still crowded the border beyond the tents. I watched as a few took in a breath and decided to chance the swirling, dust-filled barrier, their backs fading into the space between. No one bothered to stop them. They wouldn’t make it. Most would fall victim to the toxic air within the barrier. Some would slip into the cracks that opened up into the earth below. You needed a guide – someone who knew the way, who could hold their breath long enough to make headway and who had a strong natural resistance to the aether.

That was what I needed to find if Rasha and I were to make it before restoration hit us. We weaved in and out of weeping mothers, terror-stricken children, between those who had at the last moment turned faithful and dropped to their knees to pray. We dodged a few who had changed their minds, who ran toward restoration with open arms.

I was an arrow, drawn and loosed with only one purpose.

None of the groups I spotted by the wall looked suitable. The mercenaries – they wouldn’t take me on. The horse breeders with mounts much finer than the stubby ponies that habited the Kashani coastline – I had nothing to offer them. And then, just when I’d begun to grit my teeth against despair, I saw a group of sinkhole miners.

Their clothing was rough, fingers blackened from working the mines. Their faces were lean and hard, muscles like corded ropes. I counted eleven, plus one foreman who was negotiating with a guide. An odd number, which meant they’d lost someone. Sinkhole miners always worked in pairs.

Which meant there was an opening.

There were other stragglers near to them, pressing at the group, begging the miners to take them with them. To take their children or their wives. They pushed these people back, sometimes with a flat hand, sometimes with a fist or a foot. I turned to Rasha as I unslung my pack. “Stay here. Stay right here and I’ll be back.”

Her eyes, a softer brown than mine, brimmed with tears. “Hakara. Don’t go. Don’t leave me here. I can’t—”

“Hush.” I ran a hand over her dark hair. “I wouldn’t leave you. But miners are rough people. I want you to be safe, and we still have a little time. I’ll be back, I promise. Would I break that promise? Have I ever broken that promise?”

A tremulous smile touched her lips. “No.”

I gave her one last pat on the shoulder before I turned to the mining crew and picked my way across the rocks. Sinkhole mining was hard, dangerous work. The sinkholes opened up and just as quickly collapsed, often taking miners with them. It meant crossing the first aerocline into the aether below – the same toxic air that filled the barriers. If you couldn’t hold your breath for long enough while you dug the gems from the side of the sinkhole, you’d succumb. Diving into the ocean was less dangerous.

If I became a miner, I couldn’t always promise Rasha I’d come home. But we’d be in Langzu. We’d both be alive.

Panic described the foreman to me in flashes. A roughly stubbled chin, black dust settling into the cracks of his wide face. A bald pate, and arms as thick as his legs. He might not have heard my approach; the din surrounding us drowned out my footsteps. Still, he did not turn even as I addressed him.

“You’re short a crew member.”

“I’ll pay you the re

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...