- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

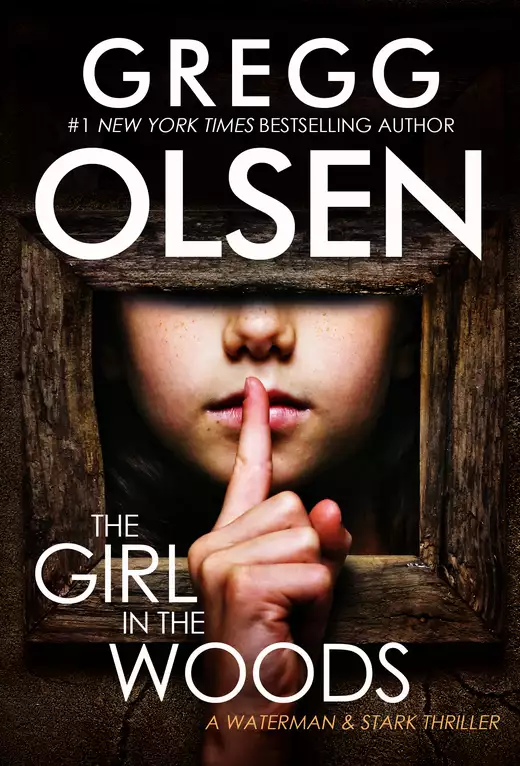

Synopsis

A schoolgirl found it on a nature hike. A severed human foot wearing pink nail polish. A gruesome but invaluable clue that leads forensic pathologist Birdy Waterman down a much darker trail-to a dangerous psychopath whose powers of persuasion seem to have no end. Only by teaming up with sheriff's detective Kendall Stark can Birdy hope to even the odds in a deadly game. It's a fateful decision the killer wants them to make. And it's the only way Birdy and Kendall can find their way to a murderer who's ready to kill again...

Release date: October 28, 2014

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Girl in the Woods

Gregg Olsen

Great! Where are those keys?

“Hang on,” she said into the phone, grabbing a tissue and wiping off her hand. “Everything happens at once. Someone’s here. I’ll be there in fifteen minutes.”

She swung the door open. On her doorstep was a soaking wet teenaged boy.

“Make that twenty,” she said, pulling the phone away from her ear.

It was her sister’s son, Elan.

“Elan, what are you doing here?”

“Can I come in?” he asked.

“Hang on,” she said back into the phone.

“Wait, did I get the date wrong?” she asked him.

The kid shook his head.

Birdy looked past Elan to see if he was alone. He was only sixteen. They had made plans for him to come over during spring break. He hadn’t been getting along with his parents and Birdy offered to have him stay with her. She’d circled the date on the calendar on her desk at the Kitsap County coroner’s office and on the one that hung in the kitchen next to the refrigerator. It couldn’t have slipped her mind. She even made plans for activities that the two of them could do—most of which were in Seattle, a place the boy revered because it was the Northwest’s largest city. To a teenager from the Makah Reservation, it held a lot of cachet.

“Where’s your mom?” Birdy asked, looking past him, still clinging to her cell phone.

The boy, who looked so much like his mother—Birdy’s sister, Summer—shook his head. “She’s not here. And I don’t care where she is.”

“How’d you get here?”

“I caught a ride and I walked from the foot ferry. I hitched, but no one would pick me up.”

“You shouldn’t do that,” Birdy said. “Not safe.” She motioned him inside. She didn’t tell him to take off his shoes, wet and muddy as they were. He was such a sight she nearly forgot that she had the phone in her hand. Elan, gangly, but now not so much, was almost a man. He had medium length dark hair, straight and coarse enough to mimic the tail of a mare. On his chin were the faintest of whiskers. He was trying to grow up.

She turned away from the teen and spoke back into her phone.

“I have an unexpected visitor,” Birdy said. She paused and listened. “Everything is fine. I’ll see you at the scene as soon as I can get there.”

Elan removed his damp dark gray hoody and stood frozen in the small foyer. They looked at each other the way strangers sometimes do. Indeed they nearly were. Elan’s mother had all but cut Birdy out of her life over the past few years. There were old reasons for it, and there seemed to be very little to be done about it. The sisters had been close and they’d grown apart. Birdy figured there would be reconciliation someday. Indeed, she hoped that her entertaining Elan for spring break would be the start of something good between her and Summer. Her heart was always heavy when she and her sister stopped speaking.

As the Kitsap County forensic pathologist, Dr. Birdy Waterman had seen what real family discord could do. She was grateful that hers was more of a war of words than weapons.

“You are going to catch a cold,” she said. “And I have to leave right this minute.”

Elan’s hooded eyes sparkled. “If I caught a cold would you split me open and look at my guts?” he asked.

She half smiled at him and feigned exasperation. “If I had to, yes.” She’d only seen him a half dozen times in the past three years at her sister’s place on the reservation. He was a smart aleck then. And he still was. She liked him.

“I’ll be gone awhile. You are going to get out of all of your wet clothes and put them in the dryer.”

He looked at her with a blank stare. “What am I supposed to wear?” he asked. “You don’t want a naked man running around, do you?”

She ignored his somewhat petulant sarcasm.

Man? That was a stretch.

She noticed Elan’s muddy shoes, and the mess they were making of her buffed hardwood floors, but said nothing about that. Instead, she led him to her bedroom.

“Uninvited guests,” she said, then pretended to edit herself. “Surprise guests get a surprise.” She pulled a lilac terry robe from a wooden peg behind her bedroom door.

“This will have to do,” she said, offering the garment.

Elan made an irritated face but accepted the robe. He obviously hated the idea of wearing his aunt’s bathrobe—probably any woman’s bathrobe. At least it didn’t have a row of pink roses around the neckline like his mother’s. Besides, no one, he was pretty sure, would see him holed up in his aunt’s place.

“Aunt Birdy, are you going to a crime scene?” he asked. “I want to go.”

“I am,” she said, continuing to push the robe at him until he had no choice but to accept it. “But you’re not coming. Stay here and chill. I’ll be back soon enough. And when I get back you’ll tell me why you’re here so early. By the way, does your mom know you’re here?”

He kept his eyes on the robe. “No. She doesn’t. And I don’t want her to.”

That wasn’t going to happen. The last thing she needed was another reason for her sister to be miffed at her.

“Your dad?” she asked.

Elan looked up and caught his aunt’s direct gaze. His dark brown eyes flashed. “I hate him even more.”

Birdy rolled her eyes upward. “That’s perfect,” she said. “We can sort out your drama when I get back.”

“I’ m—”

She put her hand up and cut him off. “Hungry? Frozen pizza is the best I’ve got. Didn’t have time to bake you a cake.”

She found her keys from the dish set atop a birdseye maple console by the door and went outside. It had just stopped raining. But in late March in the Pacific Northwest, a cease-fire on precipitation only meant the clouds were taking a coffee break. Jinx, the neighbor’s cat, ran over the wet pavement for a scratch under her chin, but Birdy wasn’t offering one right then. The cat, a tabby with a stomach that dragged on the lawn, skulked away. Birdy was in a hurry.

She dressed for the weather, which meant layers—dark dyed blue jeans, a sunflower yellow cotton sweater, a North Face black jacket. If it got halfway warm, she’d discard the North Face. That almost always made her too hot. She carried her purse, a raincoat, and a small black bag. Not a doctor’s bag, really. But a bag that held a few of the tools of her trade—latex gloves, a flashlight, a voice recorder, evidence tags, a rule, and a camera. She wouldn’t necessarily need any of that where she was going, but Dr. Waterman lived by the tried and oh-so-true adage:

Better safe than sorry.

As she unlocked her car, a Seattle-bound ferry plowed the slate waters of Rich Passage on the other side of Beach Drive. A small assemblage of seagulls wrestled over a soggy, and very dead, opossum on the roadside.

Elan had arrived early. Not good.

Birdy pulled out of the driveway and turned on the jazz CD that had been on continuous rotation. The music always calmed her. She was sure that Elan would consider it completely boring and hopelessly uncool, but she probably wouldn’t like his music either. She needed a little calming influence just then. Nothing was ever easy in her family. Her nephew had basically run away—at least as far as she could tell. Summer was going to blame her for this, somehow. She always did. As Birdy drove up Mile Hill Road and then the long stretch of Banner Road, she wondered why the best intentions of the past were always a source of hurt in the present.

And yet the worst of it all was not her family, her nephew, or her sister. The worst of it was what the dispatcher from the coroner’s office had told her moments just before Elan arrived.

A dismembered human foot had been found in Banner Forest.

Tracy Montgomery had smelled the odor first. The twelve-year-old and the other members of Suzanne Hatfield’s sixth grade Olalla Elementary School class had made their way through the twists and turns of a trail understandably called Tunnel Vision toward the sodden intersection of Croaking Frog, when she first got a whiff. It was so rank it made her pinch her nose like she did when jumping in the pool at the Y in nearby Gig Harbor.

“Ewww, stinks here,” the girl said in a manner that indicated more of an announcement than a mere observation.

Tracy was a know-it-all who wore purple Ugg boots that were destined to be ruined by the muddy late March nature walk in Banner Forest, a Kitsap County park of 630-plus acres. She’d been warned that the boots were not appropriate for the sure-to-be-soggy trek inside the one-square-mile woods that were dank and drippy even on a sunny spring day. There was no doubt that Tracy’s mother was going to survey the damage of those annoyingly bright boots and phone a complaint into the principal’s office.

“That’s why they call it skunk cabbage,” said Ms. Hatfield, a veteran teacher who had seen the interest in anything that had to do with nature decline with increasing velocity in the last decade of her thirty-year teaching career. She could hardly wait until retirement, a mere forty-four school days away. Kids today were all but certain that lettuce grew in a cellophane bag and chickens were hatched shaped like nuggets.

Ms. Hatfield brightened a little as a thought came to mind. Her mental calculations hadn’t been updated to take into account this day.

Technically, she only had forty-three days left on the job.

A squirrel darted across the shrouded entrance to Croaking Frog, turned left, then right, before zipping up a mostly dead Douglas fir.

“My dad shoots those in our yard,” Davy Saunders said. The schoolboy’s disclosure didn’t surprise anyone. Davy’s dad went to jail for confronting an intruder—a driver from the Mattress Ranch store in Gorst—with a loaded weapon. The driver’s crime? The young man used the Saunders driveway to make a three-point turn.

“Want to hear something really gross?”

This time the voice belonged to Cameron Lee. He was packed into the middle of the mass of kids and two beleaguered moms clogging the trail. “My cousin sent me a video that showed some old guy cutting up a squirrel and cooking it. You know, like for food.”

Ms. Hatfield considered using Cameron’s comment as a learning moment about how some people forage for survival, but honestly, she was simply tired of competing with reality TV, the Internet, and the constant prattling of the digital generation. They knew less and less it seemed because they simply didn’t have to really know anything.

Everything was always at their fingertips.

Ms. Hatfield knew the Latin name for the skunk cabbage that had so irritated Tracy’s olfactory senses—Lysichiton americanus—but she didn’t bother mentioning it to her students. Instead, she sighed and spouted off a few mundane facts about the enormous-leafed plant with bright yellow spires protruding from the muddy soil like lanterns in a dark night.

“It smells bad for a reason,” she said. “Anyone know why?”

She looked around. Apparently, no one did. She glanced in the direction of Viola Mertz, but even she didn’t offer up a reason. The teacher could scarcely recall a moment in the classroom when Viola didn’t raise her hand.

If she’d lost Viola, there was no hope.

Ms. Hatfield gamely continued. “It smells bad to attract—”

“Smells like Ryan and he can’t attract anyone,” Cooper Wilson said, picking on scrawny Ryan Jonas whenever he could.

Ms. Hatfield ignored the remark. Cooper was a thug and she hoped that when puberty tapped Ryan on the shoulders, he’d bulk up and beat the crap out of his tormentor. But that would be later, long after she was gone from the classroom.

“. . . to attract pollinators,” she went on, wondering if she should skip counting days left on the job and switch to hours. “Bugs, bees, flies, whatever.”

“I’m bored,” Carrie Bowden said.

Ms. Hatfield wanted to say that she was bored too, but of course she didn’t. She looked over at one of the two moms who’d come along on the nature hike—Carrie’s mom, a willowy brunette named Angie, who had corked ear buds into her ears for the bus ride from the school and hadn’t taken them out since. Cooper Wilson’s mom, Mariah, must be bored too. She flipped through her phone’s email, cursing the bad reception she was getting.

“It might smell bad,” Ms. Hatfield said, trying to carry on with her last field trip ever. “But believe it or not this plant actually tastes good to bears. They love it like you love a Subway sandwich.”

Only Cooper Wilson brightened a little. He loved Subway.

“Indigenous people ate the plant’s roots too,” the teacher went on. She flashed back to when she first started teaching and how she’d first used the word Indians, then Native Americans, then, and now, indigenous people.

Lots of changes in three decades.

“Skunk cabbage might smell bad,” she said, “but it had very important uses for our Chinook people. They used the leaves to wrap around salmon when roasting it on the hot coals of an alder wood fire.”

“I went to a luau in Hawaii and they did that with a pig,” Carrie piped up, not so much because she wanted to add to the conversation, but because she liked to remind the others in the class that she’d been to Hawaii over Christmas break. She brought it up at least once a week since her sunburned and lei-wearing return in January. “They wrapped it up in big green leaves before putting it into the ground on some coals,” she said. “That’s what they did in Hawaii.”

“Ms. Hatfield,” Tracy said, her voice rising above the din of not-so-nature lovers. “I need to show you something.”

Tracy always had something to say. And Ms. Hatfield knew it was always super important. Everything with Tracy was super important.

“Just a minute,” the teacher said, a little too sharply. She tried to diffuse her obvious irritation with a quick smile. “Kids, about what Cameron said a moment ago,” she continued. “I want you to know that a squirrel is probably a decent source of protein. When game was scarce, many pioneers survived on small rodents and birds.”

“Ms. Hatfield! I’m seriously going to puke,” Tracy called out. Her voice now had enough urgency to cut through the buzzing and complaining of the two dozen other kids on the field trip.

Tracy knew how to command attention. Her purple Uggs were proof of that.

Ms. Hatfield pushed past the others. Her weathered but delicate hands reached over to Tracy.

“Are you all right?” she asked.

The girl with big brown eyes that set the standard for just how much eye makeup a sixth grader could wear kept her steely gaze focused away from her teacher. She faced the trail, eyes cast downward.

Tracy could be a crier and Ms. Hatfield knew she had to neutralize the situation—whatever it was. And fast.

“Honey, I’m sorry if the squirrel story upset you.”

The girl shook her head. “That wasn’t it, Ms. Hatfield.”

The teacher felt relief wash over her. Good. It wasn’t something she said.

“What is it?”

Tracy looked up with wide, frightened, almost Manga eyes.

“Are you sick?” the teacher asked.

Tracy didn’t say a word. She looked back down and with the tip of her purple boot lifted the feathery stalk of a sword fern.

At first, Ms. Hatfield wasn’t sure what she was seeing. The combination of a stench—far worse than anything emitted by skunk cabbage—and the sight of a wriggling mass of maggots assaulted her senses.

Instinctively, she swept her arm toward Tracy to hold her back, as if the girl was lunging toward the disgusting sight, which she most certainly was not. It was like a mother reaching across a child’s chest when she hit the brakes too hard and doubted the ability of the safety belt to protect her precious cargo.

All hell broke loose. Carrie started to scream and her voice was joined by a cacophony. It was a domino that included every kid in the group. Even bully Cooper screamed out in disgust and horror. Angie Bowden yanked out her ear buds as if she was pulling the ripcord on a parachute.

No one had ever seen anything as awful as that.

Later, the kids in Ms. Hatfield’s class would tell their friends that it was the best field trip ever.

Birdy Waterman parked her red Prius on Olalla Valley Road behind a row of marked and unmarked Kitsap County sheriff’s vehicles. She pulled on her badly wrinkled raincoat, also red, from the passenger seat and called over to Deputy Gary Wilkins, who stood next to the main trailhead. At twenty-six, he was a young deputy and this kind of thing, a dead thing, was still new to him. He was a block of a man, with square shoulders and muscular thighs. He nodded in her direction and his gray eyes flashed recognition and anxiety at the same time.

“Your turn?” he asked, already knowing the answer.

Birdy shut the car door. It was her turn. The county had a PR nightmare on its hands the previous year when a coroner’s assistant screwed up a homicide case. In an embarrassing and ultimately futile attempt to save himself, he put the blame on the sheriff’s detectives and their evidence-gathering process. It was a colossal error that hadn’t yet healed over when the coroner and the sheriff decided a “working together” rotation was the solution to all of their problems.

People in both offices could still recall the subject line of the email:

There’s no “I” in “Team.”

It was an eye-roller of the greatest magnitude.

Because of that memo, and the weeks of touchy-feely training that ensued, Birdy was standing in the muddy parking strip while the nephew she barely knew was probably burning down her house, making that sad frozen pizza she’d offered as his best bet for a hot meal. She almost never visited crime scenes, but she was in the rotation when Ms. Hatfield called 911.

“How’s the family?” Birdy asked Gary, slipping on her coat as a seam in the sky tore just enough to send down another trickle of Pacific Northwest springtime weather. She picked her way across the little ridge that separated the forest entrance from Banner Road, a nine-mile thrill ride of a two-lane blacktop that hopped up and over the hills of the southernmost edge of the county. She wore street shoes instead of boots, because distracted by her nephew’s sudden appearance on her doorstep, she hadn’t considered she’d be traipsing through the woods until she was halfway there.

Banner Forest. Stupid me, she thought.

“Good. I mean, not really,” Gary said. “Abby got a stubborn cold, which means I’m next,” he went on, referring to his two-year-old. Birdy liked Gary and right then she especially liked that he didn’t ask for advice on how to help his daughter get over her cold. She was a doctor, of course. She’d had the same training as any MD, but her patients had little need for a calm bedside manner.

They were always dead.

“What happened here?” she asked.

“No one has really said anything to me. Other than, you know, the kids apparently found part of a dead body down the trail. They were pretty freaked out.”

“I imagine they would be,” Birdy said. She indicated the row of sheriff department cars.

“Kendall here?”

Gary tipped his head toward the dark, tree-shrouded funnel-like opening of the trail that led deep into Banner Forest.

“Yup,” he said. “They’re all down there by—and you’ll love this—Croaking Frog.”

Birdy arched a brow and looked down the pathway.

“What’s that?” she asked.

“The name of the trail,” he said. Gary had found something amusing in the worst of circumstances. He’d make a very good deputy.

“Croaking Frog?” she repeated, though she was pretty sure she heard him correctly.

“Welcome to South Kitsap County,” he said. “You’ll find Kendall and the others about a hundred yards down that way.”

Birdy followed his fingertip toward the rutted trail into the woods.

Kendall Stark was a homicide detective Birdy liked working with more than the investigators in her unit in the sheriff’s office. That wasn’t to say that Birdy thought others in the Kitsap County Sheriff’s Department were any less competent at what they did. They were skilled investigators, no doubt about that. It wasn’t because Kendall was the only woman either. If that had been the reason, Birdy would never say so anyway. Saying so would surely invite more sensitivity training.

And yet, if she’d been completely honest with herself, the forensic pathologist did believe that Detective Stark had an ability to empathize with a victim’s family to a greater degree than some of her male counterparts. It wasn’t solely her gender—there were plenty of women in law enforcement who were so cerebral, so clinical, that emotions were sealed behind a fortress of their own making. Birdy had trained with several at the University of Washington who were all about CSI and crisp white lab coats and heels that thundered when they walked down corridors—an obnoxious drumbeat announcing their impending arrival.

Kendall was different from those women, Birdy thought, because she was a mother. And a good one. In Birdy’s world, a good mother—and God knew she learned that little fact the hard way—had the ability to understand the loss and suffering of others and the hurt that becomes a festering wound. Those were the cases in which a child was murdered, the darkest, saddest, of any that came across either woman’s desk. The obvious truth about any homicide was that no matter the victim’s age, he or she had a mother.

Kendall was where she needed to be—at the scene or with witnesses. Birdy needed to be in the lab.

Or at home with her nephew.

Cross training, she thought, was so irritating.

She glanced at a trail map on a sheltered kiosk behind Gary, but it looked like a crudely executed rendering of a sack full of snakes. The forest was crisscrossed by a series of hiking and horseback-riding trails that had lately been taken over by dirt bikers. Several trails—including Tunnel Vision—featured earthen ramps that sent bikers soaring into the air. When the forest was saved from development, the vision of the committee that had fought for it had been to see it used as a nature preserve, a hiking and horseback-riding trail.

Not a speedway for dirt bikes.

Birdy wondered how a dismembered foot had turned up in Banner Forest. Birdy knew that cougars had been spotted there, as well as the notorious case in which a black bear mauled a man when his dogs frightened the mother bear’s cubs.

There were two lessons there. Never let a dog off its leash. And never, ever anger a mother bear.

Birdy followed the muddy trail to the intersection of Tunnel Vision and Croaking Frog. The ground was damp from the rain, but so compacted by the dirt bikes that it wasn’t as gooey as it might have been. Tire treads laced the pathway.

As Birdy passed a NO HUNTING sign nailed to an old growth cedar stump, another possibility ran through her head.

Maybe a hunter accidentally shot a child? Thought a small figure in the woods was a deer? Deer were thick in that part of the county. Even with NO HUNTING signs posted all over the place, there were plenty of rule breakers—especially midweek when fewer people frequented the woods.

As she drew closer to Croaking Frog, she recognized the voices of the techs and Detective Stark.

Kendall looked up. Her short blond hair had grown out some and softened the angular features of her face. The spikiness was gone and the look flattered her. Even her deep blue eyes benefited from the change. “I wondered if it was your turn to be a team player,” she said.

Birdy glanced past the detective.

A tech was hunched among the sword ferns.

“There’s no I in Team,” Birdy said, recalling the obnoxious training they’d all been forced to attend to ensure that mistakes would never happen again.

“You make an Ass out of U and Me when you assume something,” Kendall said with a sigh. “Thank goodness the ass that got us all into this mess got fired.”

Birdy was grateful for that too. “No kidding,” she said. “What have we got here?”

“Not much,” Kendall said.

“No visible sign of cause?” she asked.

It wasn’t Kendall’s job to determine what happened to any victim, of course. But that didn’t stop most detectives in most jurisdictions all over the country from announcing what they were “pretty sure” had occurred.

Kendall shook her head. “No, not that. What I mean is not much of anything.” She pointed downward. “All we’ve got is a foot.”

Birdy wedged herself into the mossy space next to a human foot painted with a writhing mass of maggots.

“I’m not . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...