- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Leaving the heartache of sexual betrayal behind her in London, historian Sarah Thomson intends to make the most of her research trip to Venice. But she soon finds her attention consumed by mysterious millionaire Marco Donato. Despite their deepening relationship, however, the handsome playboy persists in playing a secretive game. What exactly is Marco hiding? The subject of Sarah's research is eighteenth-century Venetian Luciana Giordano. At a time when debauchery is the city's favourite pastime, virginal Luciana is kept out of trouble by a zealous chaperone - until she meets a man who promises to help her escape her restraints. But just what does the worldly stranger want to teach her in return?

Release date: March 28, 2013

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 297

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

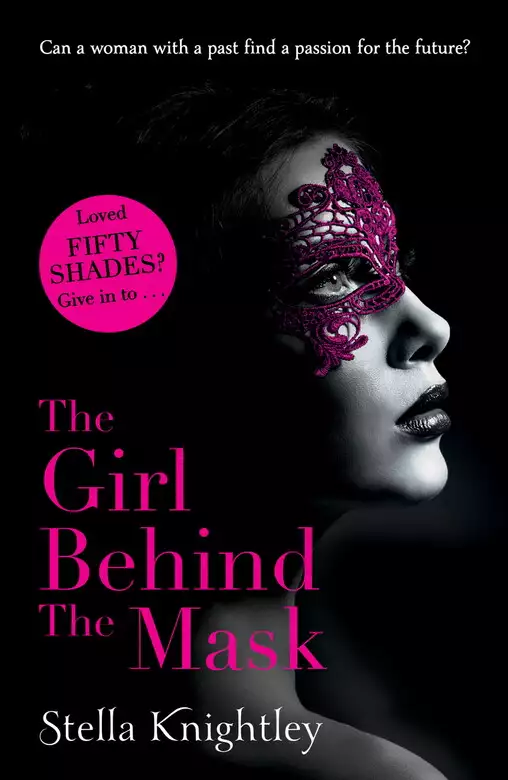

The Girl Behind the Mask

Stella Knightley

Venice, last January

You never forget the first time you see Venice.

Leaving England on the 7.40 a.m. flight from Gatwick, all I could think about was how much I wished I were still in my bed. I left the house in pitch darkness. The cold London air bore intimations of snow. Now, just two and a half hours later, I was standing by the waterside in bright sunshine. The quay at Venice’s Marco Polo airport certainly made a change from the Victoria platform for the Gatwick Express. Though it was still only January, the warmth of those unexpected rays coaxed me to unfasten my coat and loosen the thick woolly scarf I’d expected to be wearing until April. I lifted my face to the sky and let the light pour over me like a creature coming out of hibernation. I stood there in a dream state, letting the heat find my winter-weary bones, until I realised that the crowd behind me was at last boarding a boat.

The yellow-hulled municipal ferry spluttered across the shallow water, trailing a thick cloud of grey warning smoke in its wake, but nothing could detract from the beauty of that morning for me. The sunshine reflected by the shallow sandy-bottomed lagoon made it seem as though the whole world was bathed in lemon and pink and baby blue. I found myself a spot by a grubby salt-splashed window and, while my fellow passengers attended to their endlessly chirping phones, I watched life on the water. A handsome water-taxi skimmed by like a flying fish. There was just enough time to see its passengers embrace. A moment of affection for them. A small stab of poignancy for me.

On the portside, an island loomed. I craned to see a boatyard, a tiny church and a simple cottage with washing all aflutter on the line outside. And then the ferry passed Murano, where the glassmakers ply their trade, hugging close to the coast so we could almost see into the islanders’ houses. Next came San Michele, the island of the dead with its high cemetery walls and sad cypress trees. A brief moment of introspection seemed to fall over all the passengers in the ferry as we lowered our eyes in respect.

Then finally, Venice itself, almost close enough to swim to. It was exactly as it looked in the pictures. A jumble of proud campanili. Red bricks. White marble. Warm terracotta and mustard-plastered walls. A thousand wooden poles studded the water, marking out the safest routes to shore. Venice owed her success in no small part to the treachery of the lagoon, where her ancient enemies had found themselves grounded by unmarked shallows.

And there! At last! My very first gondola. I was so surprised to see it – a genuine gondola, with sleek black hull and six-pronged ferro on the prow – that I automatically turned to share my delight. But this was a quotidian view for the Venetian grandmother standing beside me.

‘Sì, gondola,’ the woman said, as though she thought me a bit slow.

‘È la mia prima,’ I explained.

The woman smiled and nodded. ‘Sì, sì.’

She knew it wouldn’t be my last.

As the boat’s captain threw the engine into reverse to bring the footbridge closer to the dock, the other passengers started to gather themselves, sensing the end of the journey. As I stepped onto the land and looked about me with appropriate wonder, I had the feeling I was just beginning mine.

Chapter 10

I glanced up at the clock and did a double take. It seemed as though I had entered the library only minutes earlier, but now the clock was telling me I had just two minutes left until the old retainer would return to escort me from the premises again. What a disaster. Even with my enormous Italian–English dictionary alongside me, I had only managed to read four pages of Luciana’s scrappy diary. Her handwriting had been difficult to decipher at first. So much so that I began to wonder if she was writing in code. Then there was the complication that Luciana’s Italian was quite unlike the modern Italian I had studied at school. Or even the Latin. And she used plenty of Venetian slang. I had no hope whatsoever of translating that in a hurry. The Venetian dialect was as foreign to me as the Arabic from which much of it derived.

I stared at the clock as though willing the hands to travel backwards. I felt as though I had only just started to hear Luciana’s voice, but at midday on the dot, the door to the library swung open and the old retainer waited impatiently while I gathered my notes and my dictionary. Please God, I muttered to myself, don’t let this be the last time I am here.

I expected the old man to accompany me all the way back to the waterside, or to the street, but instead when we got to the courtyard, he merely asked me whether I would be going back by boat or on foot.

‘On foot,’ I replied.

‘Then you need that door there,’ he said. ‘Go straight down the passage and you will emerge on to the Calle Squero. I trust you’ll find your own way. I have work to do.’

Then he turned, leaving me quite alone in the hall.

Obviously, I could not have failed to notice that my presence at the house was not entirely welcome, but with the old man gone, I couldn’t resist taking a longer look at the courtyard garden and the surrounding galleries as I passed through. The fountain still wasn’t playing, but a leaking washer somewhere in its plumbing meant that every so often a drop splashed from the fountainhead into the surrounding stone bowl, where years of such innocuous drops had eroded a little dent. Two sparrows were taking it in turns to wait for a glittering drop to fall, taking a sparrow-sized shower before they dried themselves off in the sunlight. It was magical.

Though it was still only January, there was life in this sheltered garden. London’s greenery was still deep in hibernation, but the first signs of spring were already in evidence on the edge of the Adriatic. I ran my fingers along the sharp edge of a box leaf. There was even a flower: a single winter rose, proud and beautiful and brave. I don’t know what possessed me in that moment, but suddenly, without thinking about the consequences – like Beauty’s father in ‘Beauty and the Beast’, always my favourite fairytale – I reached out and plucked the trembling white flower from its stem. I was immediately ashamed. Hiding it inside my cupped hand, I quickly headed for the door the old man had pointed out to me, my heart quickening from the excitement of my petty theft. Nobody stopped me of course but, just as when I first crossed the courtyard, I had the distinct impression that I was being watched.

Back at the university I drafted an email to Donato, thanking him for allowing me to use his library. However, I suddenly decided that it was important to make a better impression. An email would have been easy but I had actually started our correspondence with a proper, handwritten letter and perhaps that was what had made the difference. So I got out the fountain pen that my grandfather had given me on my eighteenth birthday. My lucky pen. I hardly ever used it, not least because after years of working on keyboards, I found it difficult to write more than a few paragraphs without getting cramp. But when I wanted to make a real impression, to convey to the person receiving my words that they were truly heartfelt, I brought out the pen.

Dear Mr Donato,

I want to thank you for your kindness in allowing me to visit your library this morning. I cannot tell you how much it meant to me to be able to see Luciana Giordano’s correspondence. Reading her letters, holding them in my hands, made me feel as though Luciana and I were actually talking to one another across the centuries. How wonderful it was to read a page from her diary, so vibrant and funny. It was as though she had written it yesterday. I can’t thank you enough for that experience.

I know it was no small matter for you to let a stranger into your house and for that reason I hesitate to beg your further indulgence, but I must tell you that Luciana’s writings are extremely important to my research and possibly to the wider academic community. If you were to see your way to allowing me access to those letters even one more time, it would make an enormous difference.

Though I wrote the letter in English, I signed off with a florid Italian turn of phrase, courtesy of Bea. At five o’clock, the post-boy popped his head round the office door to see if anyone had any mail to send. I picked up my letter and almost handed it over, but then decided against it. Donato’s house was just a twenty-minute walk away, assuming I didn’t get lost. It seemed ridiculous to let the post-boy take it only for it to travel to the outskirts of town to the sorting office and perhaps spend three or four days languishing there before it reached its target.

So I delivered the letter on my walk home that evening. Though I was starting to be able to orient myself I still managed to take a couple of wrong turns. Not that wrong turns in Venice are ever such a disaster, since they almost always turn up something beautiful or interesting. I felt I could wander the calli of Venice for a thousand years and never get bored. Eventually, however, I came to the street entrance of the palazzo – the one through which I had left at midday. There was no letterbox that I could see, so I rang the bell. It was at least five minutes before the old retainer appeared. He didn’t exactly exude warmth as I greeted him and showed him the letter.

‘It’s important he gets it quickly,’ I tried to explain in my faulty Italian. ‘Is he here in Venice at the moment? Because if he isn’t, then I’ll email him too. I don’t want him to think I’m not grateful for being allowed in the library this morning.’

‘He’s here,’ the old man said, nodding. ‘He is always here.’

‘Oh.’ I was surprised and, if I’m honest, a little offended then that he had not made the effort to meet me. ‘OK . . . I’ll just leave this with you.’

The old man took the letter, closing the door simultaneously, leaving me on the street wondering whether he would really pass on the letter or use it as kindling.

I waited for a moment or two, toying with the idea of knocking on the door again and asking, since Mr Donato was in, whether his servant wouldn’t mind if I delivered my thank-you note in person. But my bravado soon deserted me. If Donato hadn’t wanted to see me that morning, why would he want to see me now? Or perhaps he had seen me. Perhaps his was the shadow that had lurked in the gallery bordering the garden. Yes, that was it. He had seen me all dolled up in my very best pencil skirt and decided I wasn’t worth getting to know, unlike the long-legged, large-breasted supermodels of St Moritz and Saint Tropez. I felt myself growing hunched at the comparison.

My mobile phone vibrated in my pocket.

It was Nick.

‘Aperitivo?’ he suggested, in an exaggerated Italian accent. ‘Look for the Ponte dei Pugni. There’s a bar right at the foot of it. You can’t miss it. Everyone spills out onto the bridge.’

‘OK,’ I said. ‘Why not?’

I needed company again. I felt oddly downcast by Donato’s decision not to make my acquaintance that morning and that small rejection somehow amplified the much larger hurt I was already feeling with regard to Steven. Plus, there was something about the Donato house. It seemed to have thrown a shadow that remained with me as I walked away. There was sadness there, most definitely. But why? I glanced up at its shuttered windows one last time as I got to the end of the street. Perhaps I was going bonkers, but I was sure someone was watching me again.

Chapter 11

12th November, 1752

Night could not come quickly enough. Even though it is November and the days are supposed to be short, I felt as though darkness would never fall. The hours I spent sewing in front of the fire seemed like a year. And then, even when it was dark, I had to wait longer. Maria normally sends me up to bed at the earliest possible opportunity, but tonight of all nights she was not in any hurry. I asked if the priest was coming to take her confession. She bristled and told me the priest has gone to visit an elderly relative in Padua. Besides, she added when she realised her answer might have told me too much, she had no reason to confess. Unlike some. She nodded her head towards the windows and the darkness beyond. I knew she wanted to gossip about the people in the house across the canal but of course, she couldn’t gossip with me. More’s the pity for her. I could have added some real colour to her hearsay.

Instead we had to sit in silence, both of us frustrated. Her without the prospect of divine intervention. Me just waiting for the end of this interminable day. If only I felt Maria could be trusted. If I could have told her exactly what happened on the canal beneath my window last night, how quickly our evening together might have passed.

Anyway, I digress. At last, at last, the time came when Maria suggested I go to my bed. I had been hinting for several hours already. Yawning and sighing, complaining of dropped stitches. But I know Maria dislikes being alone in the darkened rooms of the palazzo. My father is away on business. My brother has accompanied him this time. There remains only me to keep her company. Both Maria and I knew that Fabio, my father’s boatman and general factotum, would have taken advantage of the absence of the master of the house and gone to visit his sweetheart. Lucky Fabio, having a sweetheart whose parents don’t care about her reputation at all.

So, I went to bed. I made a show of reluctance, of course, but Maria said it was her duty to ensure I didn’t fall asleep in church the following day. I agreed that would be a terrible shame, though church is where I have my best naps. Maria rarely notices because she is so busy mooning over the priest.

Maria unlaced my dress and helped me into my nightgown. She unfastened my hair and combed it out. I have told her several times she doesn’t need to comb my hair. I am perfectly capable of doing it myself. But tonight she insisted. I don’t know why. She certainly doesn’t seem to enjoy the job. Though I suppose I should be grateful she doesn’t seem to be doing the task for the pleasure of hurting me either. When she finds a knot, she very rarely bothers to untangle it. At that point she hands the comb over to me.

I washed my face and hands and Maria joined me by the prie-dieu as I said my night-time prayers. I prayed for my father and my brother, my mother in Heaven, for Maria – I was rewarded with a sort-of-smile for that – and for all those on the water that evening. Maria’s brow wrinkled.

‘All those on the water?’

‘I heard there might be a storm,’ I said.

While Maria fussed about the room, letting down the curtains round the bed and blowing out most of the candles, I completed my prayers in silence. I wasn’t sure what God would make of my request for the safe passage of my gondolier and his master, but I made it all the same.

‘Goodnight,’ said Maria.

‘Goodnight,’ I answered from my place on the pillows. Knowing she would turn round when she got to the door, I made a show of finding it hard to keep my eyes open. I let my body go limp and my eyes fall shut. I was the very image of an innocent girl in her dreams.

But as soon as the door shut behind my chaperone, my eyes were open. I listened to the sound of her footsteps in the dark. I listened for the creak of the board halfway down the corridor. She was going straight to her own room. Good. I waited for a minute or two more before I swung my legs out of bed and found my still warm slippers on the floor. I wrapped my dressing gown around me and padded to the window. Softly, I opened the shutters. There is always a danger that one of them will squeak but tonight they were good to me, complicit in my plan.

The night air rushed in. It was so cold my first breath almost stopped my heart. Such a night! Who would be out now by choice? Mist swirled along the water, curling its way up to my balcony. I listened to the campanile strike twelve and hoped I would not have to wait too long.

There was, of course, no scene being played out at the house across the canal that evening. I’d overheard Maria and the cook saying it would be a couple of weeks before the husband ventured out alone again. I leaned as far out of my window as I could to see the distant entrance to the Grand Canal. Thanks to the fog rolling in from the lagoon, I could see next to nothing, but the voices of the revellers let me know they were still there. Snatches of song, shouts and whistles met my ears, though they were softened and distant, like the voices of the dead.

You can imagine then how ghostlike was the black gondola this evening. Just this once, I heard it before I saw it. I heard the gentle slap of the oar in the water as the gondolier steered skilfully towards my house. Then I saw the polished ferro, and the gondolier’s hat. He lifted his lantern towards me. The light shining on his face, illuminating that alone, made him look like some sort of floating demon. I ducked back into my window. He whistled up.

‘Hey! Hey! It’s the Madonna of the Window.’

I leaned back out, putting my finger to my lips. He was going to get me into trouble.

‘Have you written your reply?’ he asked.

I showed him the paper, folded and sealed with a piece of string and a plain blob of wax from my bedtime candle. I don’t have a seal so I used the end of my pen to scratch my initials into it. I hoped my correspondent would understand this embarrassing lapse.

The gondolier reached up his oar and I fastened my letter to the end of it. He plucked the letter off and passed it into the felce. He tipped his hat at me and began to row away at once.

Now I feel horribly foolish. What have I done? I have sent a letter containing all my innermost secrets and frustrations to a man I do not know. He might be anybody. How could I have been so insane as to believe I could trust someone who doesn’t show his face, even in this town where no one shows his face? I imagine my letter being passed from hand to hand in some tavern. Oh, what an evening’s sport I will make for a bunch of men on the Rialto. What if the letter falls into the hands of someone who knows my brother? Or, far worse, my poor papà? I can almost hear the gates of the convent closing behind me.

I cannot sleep. I can do nothing but lie on my back and stare up at the canopy, imagining the stream of events I have just set in motion.

Chapter 12

I was quickly learning that an aperitivo with Nick always turned into an event. When I met him at the bar, Bea was already there. There were other faces I recognised from the corridors of the university and a whole host of other people I didn’t know yet, but who greeted Nick like an old friend. The proprietor of the bar seemed especially happy to see him. When Nick wrapped his arm round my shoulder – treating me to a cloud of his delicious aftershave – and took me into the bar itself, to see the sort of food that was on offer, the old proprietress gave him a beaming smile. She gave me an altogether more appraising look. It put me in mind of Donato’s old retainer.

‘And what can I get for her?’ the old woman asked, jerking her head in my direction.

I tried not to take offence. Instead, I smiled and said ‘Grazie, grazie,’ a million times as Nick picked out a selection of small bites – cichetti – he thought I might like. Then Nick ordered me a spritz – Venice’s signature tipple, a mixture of white wine, soda water and Aperol – and we went back outside. Despite the freezing weather, international students in their North Face puffa jackets and locals looking altogether more glamorous in their Prada and real fur thronged the bridge.

‘This bar has been here for centuries,’ Nick explained. ‘Bea thinks Casanova might have mentioned it.’

‘I worked it out from the location,’ Bea explained.

‘I don’t suppose it’s changed much,’ said Nick.

Bea picked up a crostino and examined it. Her nose wrinkled. ‘This has certainly been on the counter for several centuries already.’

It was true that the quality of the cichetti Nick had picked out was variable, but no one came to this particular bar to eat. They came to be seen. They came to meet old friends. They came to flirt with strangers. After two glasses of spritz, which I’d quickly got a taste for, I forgot about the cold. After three, I was delighted to join Nick and some other guys for dinner. When I finally pushed open the door to my apartment at midnight, I had the feeling I was going to have a slow sort of morning the following day.

I fell into the spooky old four-poster quite gratefully. I pulled the red velvet curtains closed to keep in the warmth and snuggled deep beneath the scratchy blankets. Laying my head down on the pillows, I thought about my morning at the Palazzo Donato.

I drifted into sleep thinking especially about the secret courtyard. I heard the drip, drip, drip of the broken fountain. I saw the statues – parted lovers frozen in time – eternally beckoning to each other across the crooked path. I saw the playful sparrows jumping in and out of the water as sunlight turned the droplets on their wings into dazzling sequins. I saw the fruit trees waiting for the first breath of spring. I saw my hand closing on the stem of the single white winter rose, breaking the sap-filled green stalk to set the blossom free. And then another hand, large and masculine, was suddenly closing around mine. I felt hot breath on the side of my face.

‘What will you give me in return for my most precious possession?’

I turned in horror. Towering over me was a man in a half-mask similar to those sold in every tourist shop in the city. He was smiling but with no intention of putting me at my ease.

I apologised for my clumsy theft, my face reddening with shame as I struggled to find the right words. I tried to step backwards but the stranger held on to my hand and unbalanced me. The rose stem was squeezed inside my palm. I waited to feel a thorn pierce my skin, but no pain came. The masked man stared at me. Behind the mask, his eyes were dark and almost animal. Like a bear’s. I was hypnotised. As I looked closer, they started to change. Far from being hard, now they seemed sad but kind. They were at odds with his cruel, twisted smile and I felt my fear begin to ebb away.

‘It’s yours,’ he said eventually. ‘It was waiting just for you.’

And then suddenly that cruel mouth was upon mine, kissing me passionately. Our two hands were still joined together round the flower. His free hand was round my waist, posed as though we were dancing. He kissed me until I ran out of breath and started wilting in his embrace. The rose was forgotten as we unlaced our hands so I could wrap both my arms around his neck. He picked me up. He was strong and certain. He lifted me as though I weighed less than the broken flower. I knew he would not drop me.

He carried me into the house, past the door to the library and on down the corridor. Still carrying me, he pushed open a door with his shoulder and took me into his chamber. In the centre of the room was a high four-poster bed made up with bright white sheets. He laid me down upon it.

Helpless with desire, I sank into the pillows. I reached my hands up to him. He stripped off his shirt. His back was wide and strong. His arms, as I had gathered when he carried me, were hewn from thick hard muscle. I stared at his body. On his chest was a scar that looked like an exploding comet. It. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...