Run.

It’s dark. So dark. Clouds scud across the charcoal sky, blanketing the moon and stars. Dampness fills my lungs and as I draw a sharp breath nausea crashes over me in sickening waves.

My energy is fading fast. My trainers slap against the concrete and I don’t think I can hear footsteps behind me any more, but it’s hard to tell over the howling wind.

I steal a glance over my shoulder but my feet stray onto soft earth and I lose my footing and stumble, splaying out my hands to break my fall. The side of my face hits something hard and solid that rips at my skin. My jaw snaps shut and my teeth slice into my tongue flooding my mouth with blood, and as I swallow it down, bile and fear rises in my throat.

Don’t make a sound.

I’m scared. So scared.

I lie on my stomach. Still. Silent. Waiting. My palms are stinging. Cheek throbbing. Rotting leaves pervade my nostrils. My stomach roils as I slowly inch forward, digging my elbows into the wet soil for traction. Left. Right. Left. Right.

I’m in the undergrowth now. Thorns pierce my skin and catch on my clothes but I stay low, surrounded by trees, thinking I can’t be seen, but the clouds part and in the moonlight I catch sight of the sleeve of my hoodie, which, unbelievably, is white, despite the mud splatters. I curse myself. Stupid. Stupid. Stupid. I yank it off and stuff it under a bush. My teeth clatter together with cold. With fear. To my left twigs snap underfoot and instinctively I push myself up and rock forward onto the balls of my feet like a runner about to sprint. Over my heartbeat pounding in my ears, I hear it.

A cough. Behind me now. Close. Too close.

Run.

I stumble forward. I can do this I tell myself, but it’s a lie. I know I can’t keep going for much longer.

The clouds roll across the sky again and the blackness is crushing. I momentarily slow, conscious I can’t see where I’m putting my feet. The ground is full of potholes and I can’t risk spraining my ankle, or worse. What would I do then? How could I get away? The wind gusts and the clouds are swept away and in my peripheral vision a shadow moves. I spin around and scream.

Run.

Every Tuesday, between four and five, I tell lies.

Vanessa, my therapist, nudges tortoiseshell glasses up the bridge of her nose and slides a box of Kleenex towards me, as if today will be the day my guilt spews out, coming to rest, putrid and toxic, on the impossibly polished table between us.

‘So, Jenna.’ She shuffles through my file. ‘It’s approaching the six-month anniversary – how do you feel?’

I shrug and pick at a stray thread hanging from my sleeve. The scent from the lavender potpourri irks me, as does the excess of shiny-leaved plants in this carefully created space, but I swallow down my agitation as I shift on the too-soft sofa. I can’t keep blaming my medication for my mood swings, can I?

‘Fine,’ I say, although that couldn’t be further from the truth. I have so many emotions waiting to pour out of me, but whenever I’m here, words tie themselves into knots on my tongue, and however much I want to properly open up, I never really do.

‘Have you been anywhere this week?’

‘I went out with Mum, on Friday.’ It’s hardly news. I do it every week. Sometimes I can’t understand why I see Vanessa at all. I’ve completed the set number of appointments I was supposed to, yet still I arrive on the dot each week. I guess it’s because I don’t get out much and I do like my routine, my little bit of normality.

‘And socially?’

‘No.’ I can’t remember the last time I had a night out. I’m only thirty but I feel double that, at least. I wasn’t up to socialising for ages afterwards and now I prefer to be at home. Alone. Safe.

‘Emotionally? Are things settling down?’

I break eye contact. She’s referring to my paranoia, and I don’t quite know what to say. At almost every hospital appointment the cocktail of drugs I am taking to stop my body rejecting my new heart is adjusted, but anxiety has wrapped itself around me like a second skin, and no matter how hard I try, I can’t shake it off.

‘The urge to…’ she consults her notes, ‘run away? Is that still with you?’

‘Yes.’ Adrenaline pricks my skin and the underarms of my T-shirt grow damp. The sense of danger that often washes over me is so overwhelming it sometimes feels like a premonition.

‘It’s not unusual to want to escape from your own life when something traumatic has happened that is difficult to process. We have to work together to break the cycle of obsessive thoughts.’

‘I don’t think it’s as simple as that.’ The fear is as real and solid as the amber paperweight that rests on Vanessa’s desk. ‘I’ve been having more…’ I’m not sure I want to tell her but she’s looking at me now in that way of hers, as if she can see right through me, ‘… episodes.’

‘Are they the same as before? The overwhelming dizziness?’ She lifts her chin slightly as she waits for my answer, and I wish I’d never mentioned it.

‘Yes. I don’t lose consciousness but my vision tunnels and everything sounds muffled. They’re getting more frequent.’

‘And how long are these episodes lasting?’

‘It’s hard to say. Seconds probably. But when it happens I feel so…’ I look around the office as though the word I am looking for might be painted on the wall, ‘… frightened.’

‘Feeling out of control is frightening, Jenna, and it’s understandable given what you’ve been through. Have you mentioned these episodes to Dr Kapur?’

‘Yes. He says panic attacks aren’t unheard of on my medication but if all goes well at my six-month check he can reduce my tablets and that should help.’

‘There you go then. And you’re due back at work…’ she glances at her papers, ‘… Monday?’

‘Yes. Only part-time though. At first.’ Linda and John, my bosses, have been more than generous with the time off they have given me. They’re friends of Dad’s and have known me most of my life, and although Linda said I shouldn’t feel obliged to return I’ve missed my job. I can’t imagine starting afresh somewhere new. Somewhere unfamiliar. I’m nervous though. I’ve been away so long. How will it feel? Being normal again. I’m jittery at the thought of mixing with people. I’ve got too used to my own company, being at home, filling my time. ‘Pottering around,’ Mum used to call it; ‘hiding myself away,’ she says now, but in my flat the jagged unease I carry with me isn’t quite so sharp. But life goes on, doesn’t it? And if I don’t force myself to start living again now I’m afraid I never will.

‘How do you feel about going back?’

My shoulders begin their automatic ascent towards my ears but I stop them. ‘OK, I think. My parents aren’t keen. They’ve been trying to talk me out of it. I can understand that they’re worried it will be too much, but Linda has said I can take it slowly to start with. Leave early if I get too tired and go in late if I’ve had a bad night.’ I’ve always had a good relationship with Linda, even if she hasn’t visited me in the past few months. She doesn’t know what to say, I suppose. No one does. The fact I nearly died makes people uncomfortable.

‘And the donor’s family? Are you still trying to contact them?’

I shift in my seat. Over the past few months I have poured my thanks into letter after letter that was rejected by my transplant co-ordinator. I’d inadvertently revealed too much. A clue about who I was, where I live. But without those details it all seemed so cold and anonymous. Eventually I paid a private investigator to find them and wrote to the family directly. It cost a small fortune just for their address but it was worth it to be able to express how grateful I am and how much their act means to my family, without filtering my words. I wasn’t going to bother them again and never expected to hear back but they replied straight away, and seemed genuinely pleased to have heard from me. I know Vanessa won’t like what’s coming.

My mouth dries and I lean forward to pick up my glass. My hand trembles and ice cubes chink and water sloshes over the side and trickles onto my lap where it soaks into my jeans. I sip my drink, conscious of the tick-tick-tick of Vanessa’s clock, discreetly positioned behind me. ‘I’m meeting them on Saturday.’

‘Oh, Jenna. That’s completely unethical. How did you trace them? I’m going to have to report this, you know.’

My face flames as I study my shoes. ‘I can’t tell you. I’m sorry.’

‘You know contact isn’t encouraged.’ Disapproval drips from every word. ‘Especially this early on in the process. It can be incredibly distressing for everyone, and it could set you back several stages. A simple thank you letter would have sufficed but meeting – I just…’

‘I know. They’ve been told exactly the same thing, but they want to meet me. They do. And I need to meet them. Just once. It feels as though someone else is inside of me, and I want to know who it is. I have to know.’ My voice cracks.

‘It’s become almost an obsession and it’s not healthy, Jenna. What good will it do you knowing whose heart you have?’

The colours in the painting behind her, something modern and chaotic, swirl together and the gnawing agitation inside me grows.

‘It would help me to understand.’

‘Understand what?’ Vanessa leans towards me like a jockey on a horse, pushing forwards, sensing a breakthrough.

‘Why I lived and they died.’

There’s an indent in my chocolate leather couch marking the place I’ve spent too many hours. There might as well be a sign,

‘girl with no life lives here’

I light a berry-scented candle before flopping down in my usual spot. I always feel so drained when I’ve been to see Vanessa, and I’m never sure whether it’s from the emotions that bubble to the surface when I sit in her immaculate office, or the effort of keeping them inside.

From the coffee table, I pick up my sketchbook. Drawing always relaxes me. I stream James Bay through my Bluetooth speaker and as he holds back the river I tap-tap-tap the pencil hard against my knee, staring at the bland walls as I wait for inspiration to hit. I’ve been meaning to decorate since Sam moved out nearly six months ago. Make the flat my own. Cover up the magnolia with sunshine yellow or rich red: bold colours that Sam hates. It’s not like he’s coming back although I know he’d like to. He never wanted us to split up but I couldn’t stand the look of sympathy in his eyes whenever he looked at me after my surgery, the way he fussed around asking if I was all right every five minutes. I didn’t want him to be stuck with someone like me, ‘helping me through’ as though we’re old and there’s nothing more to life. Cutting him free was the kindest thing I’ve ever done, even if my stomach still twists every time I think about him. We’re trying to be friends. Texting. Facebooking. But it’s not the same, is it? I add decorating to my mental list of things to do that I’ll probably never get around to. The days when I had to take it easy have passed but I’m stuck in a rut I can’t get out of and, truth be told, I’m scared. Despite the hours of physio and the mountain of leaflets I was sent home with, there’s a hesitancy about my movements. An enforced slowness. My body is healing well, my doctor says, but my mind doesn’t seem to believe it, and I’m terrified I will push myself too hard. That something will go wrong, and what would I do then? I picture myself lying on the floor. Unable to reach the phone. Unable to move. Who would know? I pretend to Mum I’m fine living alone. I pretend to everyone. Even myself.

What can I draw? I flick through the pages of my pad. Initially there is image after image of Sam, but lately my drawings have become darker. Menacing almost. Forests with twisted tree branches, eyes peering out of the gloom, an owl with beady eyes. I sigh. Perhaps Vanessa is right to be concerned about my mental health.

My mobile beeps. It’s a text from Rachel, and I know without opening it she’ll be asking what I’m doing later. I’ll tell her I’m having a night in and to have a drink for me at the pub. It’s our weekly routine, like Punch and Judy. The same every time even though sometimes you itch for a different ending. I could go, I think to myself but then I bat the thought away. It seems fruitless to try to fall back into the same habits. I’m not the person I was before, and besides, people treat me differently now, never quite meeting my gaze, not knowing what to say. I’ll see Rachel at work on Monday.

Nearly six months ago, someone died so I can live. My world has become so small it sometimes feels as though I can’t breathe. Who was it that died for me? I squeeze my eyes tightly closed but the thought still juggernauts towards me and I don’t know how to make it stop. I shiver and cross to the window. The breeze blowing in is freezing but I am grateful for the fresh air. I have been home for weeks now but the heavy smell of hospital seems to have embedded itself into my lungs, and whatever the weather I always have the windows cracked open. I peer out of the slatted blinds into the dusk and a chill creeps up my spine. A shadow shifts in the doorway across the road, and the urge to run I told Vanessa about swamps me. My breath quickens but the street is still. Quiet. I slam the window and close the blinds and am cocooned by the dim light in my living room. My world is shrinking; my confidence too.

Back on the sofa, my hands are shaking too much to hold the pencil steady. I’m safe, I tell myself. So why don’t I feel it?

Ten months ago, we’d both been ill. A virus had rocketed around Sam’s office, and I’d come home from work one day to find him huddled on the sofa, duvet draped over him, a pile of scrunched-up tissues on the floor. Radiators belted out heat, and I’d thrown off my coat and jumper.

‘I think I’m dying, Jenna,’ Sam croaked, stretching his arm towards me, and I’d laughed but as I took his hand it was slick with sweat, and I pressed my palm to his forehead. Despite the fact his teeth were rattling together with cold, he was burning up.

‘Man flu.’ I’d grazed my lips against his hot cheek. ‘Be back soon.’

I’d dashed out to the late-night chemist and stocked up on Lemsip and aspirin, and at home I warmed through chicken and sweetcorn soup. A couple of days later my throat stung, eyes streamed and I shivered so furiously I bit my tongue. We stayed in bed for days. The air grew thick and sour as we binge-watched box sets, volume blaring to drown out hacking coughs. We took it in turns to shuffle to the kitchen, slow and purposeful, like zombies, and fetched snacks we couldn’t swallow, drinks we couldn’t taste. It was such a relief to feel better. To hoist open the sash windows and let the cool breeze sweep away the stench of ill health. Under the shower, hot needles of water peppered my skin and I believed the worst was over.

Sam’s strength returned day by day, but mine didn’t and after about a week I felt so exhausted I was napping in the car during my lunch break, falling asleep on the couch as M&S ready meals blackened in the oven. At night, I’d wake gasping, trying to force oxygen into my lungs, and I’d stick my head out the window and gulp fresh air, wondering what was happening to me.

‘I’ve booked you a doctor’s appointment,’ Sam said one day. ‘Five o’clock. No arguing.’

I was too drained to protest. I sat in the GP’s waiting room, the fug of illness stale and oppressive. The doctor barely listened to my symptoms before he scratched his salt-and-pepper beard and told me what I was experiencing was completely normal and I just needed to rest. He reassured me that my energy would return.

Three weeks later I barely had the strength to get out of bed. I hadn’t been to work in over two weeks.

‘This doesn’t seem right to me,’ Sam said as he stood over me, his face etched with worry. ‘I’ve booked you an appointment to get a second opinion. I’ll be back to pick you up at lunchtime.’

Later that morning I’d hefted myself out of bed and was shuffling to the bathroom when I stopped to scoop the post up from the doormat, and that was the last thing I remembered. Apparently, Sam found me on the hallway floor, lips drained of colour, and I was rushed into hospital, sirens blaring, blue lights flashing.

The next few months were a blur. On one level, I was aware of what was going on around me. I had viral myocarditis which had aggressively attacked my heart function; and a transplant was my only option. Sam was permanently curled up in a ball in the chair next to my bed. Mum plastered on her bright, happy smile and visited every day. Dad paced around the room, hands in pockets, head bowed. The beeping of the machines was the last thing I heard at night and the sound I woke up to in the morning, wondering where I was until I inhaled. There’s nothing quite like the smell of hospitals, of disinfectant mixed with decay; hand gel mingled with hope. I was too weak to read, and I couldn’t focus on the TV.

‘Kardashians or soap stars?’ Rachel would ask as she read aloud from the gossip magazines, but I’d drift in and out of sleep and never could quite keep up with who was divorcing who, or which actress was currently too fat. Too thin. It all seemed so trivial, the things we used to laugh about in the pub, but I was grateful for her company. None of my other friends came to see me.

Before indistinguishable meals arrived on rattling trolleys Mum would prop me up against pillows. I never equated the fact she could hoist me up in bed with the amount of weight I’d lost. She’d cut soft hospital food into small pieces and I’d swallow them whole, too exhausted to chew. What must have run through her mind? Memories of the chubby toddler I was, strapped into my white plastic highchair, mouth open wide like a baby sparrow. How did she cope? I never saw her cry, not once. What no one told me was the doctors thought it was highly unlikely a heart would be found in time. I was dying. The transplant lists were flooded, and although I wasn’t well enough to go home, I wasn’t a priority either. How do you prepare for the worst? I can’t imagine. And I ache when I think of what they must have gone through: Mum, Rachel and Sam sitting around my bed, fingers laced together, as they prayed to a God they didn’t believe in. Dad, helpless and frustrated, visited every day but never stayed for long, and when he spoke there was an edge to his voice as if he was permanently furious, and he probably was. You don’t expect to watch your only child fade away in front of you, do you? Time was interminable: doctors consulted, nurses fussed and notes were made until, one day, a miracle happened.

‘We’ve found a heart,’ Dr Kapur announced.

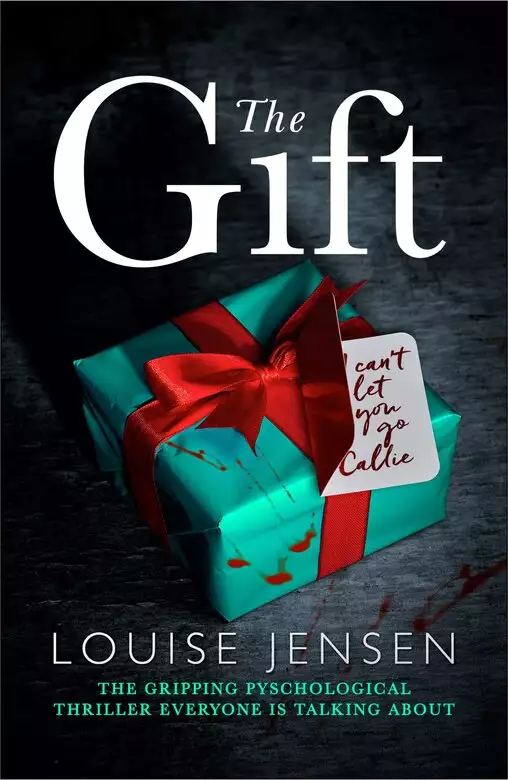

The heart was a perfect match but there was no celebration as I was prepped for surgery; everyone painfully aware this gift of life only came to fruition through another family’s grief.

The trolley wheels squeaked as I was rolled down the corridor, harsh overhead lights so white it was as if I could be sucked into their brightness and transported to an afterlife I desperately wanted to believe in.

I didn’t think it was possible to feel any worse, but when I woke two days afterwards in intensive care, I felt so ill I almost wished I’d died. Fluids were fed through tubes in my arm, and my chest drain felt as heavy as lead.

One day, by the side of my bed, Sam dropped to one knee, and at first I’d thought it was through exhaustion. I’d reached for the buzzer to call for the nurse when I noticed the black velvet box resting on his palm. A ring – oval sapphire surrounded by sparkling diamonds – inside.

‘This isn’t the romantic setting I’d envisaged, but marry me? Please?’ he’d asked.

‘Sam?’ I didn’t know what to say.

He had lifted the ring from the box and held it towards me. I ran my finger over the stone which was as deep a blue as the ocean.

‘It was Grandma’s. She wanted me to start a new tradition. Passing it down along the family.’

I swallowed hard. My head battling my heart.

‘I can buy another if you don’t like it?’

Sam looked uncertain, younger than his thirty years, and it took every ounce of willpower not to cry. I curled my fingers to stop him sliding the ring on. I knew I’d never want to take it off.

‘I can’t marry you,’ I whispered. ‘I’m so sorry.’

‘Why not? We’ve talked about it before.’

‘Everything is different now. I’m different.’

‘You’re still you.’ He stroked my cheek with such tenderness it was all I could do not to fall into his arms. Despite my unwashed hair, my stale breath, he gazed at me as if I was the most beautiful woman in the world. It tore me apart to look into his eyes and see worry reflected from the place lust once sat.

‘I don’t want to be with you any more, Sam.’ I forced out the words that hurt more than the scalpel that had sliced through my skin.

‘I don’t believe you, Jenna.’

‘It’s true. I’d been having second thoughts about us before all this.’

‘It’s just because you’re ill…’

‘It’s not. I’ve been having doubts for ages. I’m so sorry.’

‘Since when? Everything was fine before?’

Before. Such an innocuous word but there would always be a divide. Before and after. A glass wall separating the things I could do then with the things I couldn’t do any more.

‘Jenna, be honest. Do you love me?’

I was at a crossroads. Truth or lies.

‘I don’t love you, Sam.’ I chose lies. ‘I’m so sorry.’ It was the right thing to do. For him. Sam began to speak but I couldn’t meet his eye. I twisted the starched corner of the bed sheet between my fingers and willed myself to stay strong. He would be better off without me.

He put the ring back in the box, and I jumped as he snapped it shut and crossed the room, his shoulders slumped. I longed to call him back and tell him, of course I loved him, but the words were shackled to my tongue. He hesitated in the doorway and I bit the inside of my cheek hard to stop myself crying his name, my mouth full of metallic blood and regret, and as he carried on walking my gifted heart and guilt pulsed away inside of me.

Four weeks after my transplant I was discharged from hospital. Mum picked me up.

‘Where’s Dad?’

She ignored the question. She had settled me into the back seat of a taxi showing as much care as the new fathers leaving the maternity wing, clutching car seats cradling newborn babies, and dreams of a perfect future. Mum clicked my seatbelt into its holder despite my protests that I could do it myself and shook out a cotton-wool-soft plaid picnic blanket, placing it over my knees.

‘My daughter’s had a heart transplant. Please drive slowly,’ she said.

‘Blimey.’ The cabbie twisted the dial on his stereo and the music grew fainter. ‘You’re a bit young for that love, aren’t you? Kids! Always a worry, aren’t they? I’ve got three myself. Grandkiddies too.’

The taxi rumbled forward, and the traffic light air freshener swung from the interior mirror, its smell sickly-sweet. We’d crawled along at a snail’s pace – Mum not flinching at the cacophony of horns demanding we speed up – towards the three-bedroom bungalow I’d grown up in.

‘Paint It Black’ began to play: the Rolling Stones were one of Dad’s favourites, and over the music Mum chatted to the driver about what a mild winter it was so far. I closed my eyes, resting my heavy head against the window, slipping off into sleep. The vibrations from the engine made my cheeks tingle.

The sound of shouting roused me. Hard, angry voices climbing in pitch. Dazed I started to push myself upright, forcin. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved