It was on a wet Thursday morning, while she was struggling to attach a daffodil to a sprig of blossom, that Connie McColl recognised the stirrings of restlessness again. Not only that – as a result of her daydreaming, she’d managed to tape her finger into the flower arrangement as well, and swore under her breath as she unpeeled it all. She glanced down at what she hoped was an artistic impression of ‘Spring to Life’, today’s theme, and then studied the fifteen women in the class, all chattering away as they wrestled with bits of evergreen, sprigs of blossom and the inevitable daffodils. They all seemed happy enough. What is it with me? Connie wondered. Single again for nearly three years, so what was there to escape from? I’m sixty-nine, she thought, and I’m supposed to be grown up…

This group of ladies had been disappointed when she’d told them that she wouldn’t be continuing with the flower-arranging classes after Easter. Why not? they wanted to know. Why not indeed? Connie wasn’t certain herself why not. Was it purely that she fancied escaping the unpredictability of the British summer ahead? But it wasn’t just that. In truth, she knew what it was. It was her exciting new discovery.

She looked at Mrs Briggs, right there in the front row, who’d plainly given up on her ‘Spring to Life’, which was now in a state of collapse on the table. She was deep in conversation with the woman next to her, whose name Connie could never remember, about the problems with daughters-in-law. And there seemed to be plenty of them; in fact Connie could have contributed a few of her own.

Connie had enjoyed the classes until now: ‘Autumn Leaves’, ‘Christmas Table Arrangements’, ‘Here Comes Spring/Summer’ and the rest. She had to dream up seasonal names to enhance these Thursday morning gatherings of mature ladies, hell-bent on brightening up their suburban lives under mostly grey London skies.

It was the end of the final lesson before Easter and, as always, the same two women stayed on behind to help Connie clear up the debris: little Maggie scratching away with a nearly bald broom in an attempt to extract squashed catkins from the floorboards, and Gill mopping up puddles of water and discarded leaves on the table tops. Floristry was messy.

‘A right bleedin’ mess,’ confirmed Gill, never one to mince her words, as she attempted to tuck a stray blonde tendril back into its wobbly beehive, which Connie reckoned must have been a real wow back in the sixties.

‘Will you really not be doing these classes again?’ Maggie asked anxiously. She still had a Glaswegian accent you could cut with a skean-dhu, even after forty years in London.

‘I’m afraid not,’ said Connie.

Maggie Holmes had admitted that she’d only enrolled in the flower-arranging class because her friend, Pam, was going. Pam said that Maggie needed to get out more instead of hanging around waiting for that man to come home. So Maggie did as she was told, and then Pam didn’t join because she’d forgotten she was going on holiday and would miss two whole sessions. ‘How could you forget you were going on holiday?’ Maggie had asked. She herself hadn’t had a proper holiday in years and she most certainly would not be forgetting if she was lucky enough to have one in the pipeline.

Maggie sighed. ‘So no more Thursday morning flowers then?’

Connie shook her head. ‘I don’t think so, Maggie.’

‘Don’t laugh but I never meant to sign up for a flower-arranging class,’ Gill said. ‘I thought I was enrolling for a life-drawing class.’

‘A life-drawing class!’ Maggie exclaimed. ‘Are you artistic then?’

‘Not really. I just hoped I might see some naked manly bodies. But somehow or other I clicked on the wrong box, and didn’t know how to change it.’

All three of them burst out laughing.

‘Aw, Connie!’ Maggie went on. ‘Who am I going to giggle with on Thursday mornings?’

Connie had become fond of the pair of them, different as haggis and hairspray, in spite of the fact that neither displayed any particular talent for the dainty business of flower arranging. Connie reckoned most of these older ladies came along mainly for companionship and gossip, and perhaps a little therapy woven into their home-going masterpieces.

‘Tell you what,’ she said. ‘I don’t know about Thursday mornings but, right now, why don’t we go across to the pub and I’ll buy you both a lunchtime drink.’

‘Hey, thanks, Connie, I’m up for it!’ said Gill.

Maggie hesitated only for a moment. Then: ‘Och, why not?’

Ten minutes later they’d found themselves a wobbly corner table in the Dog and Duck, where Maggie folded a tissue neatly under the offending table leg. ‘There, now,’ she said. Maggie was like that: practical. Connie looked round at the gloomy Victorian interior, its walls still yellowed from decades of cigarette smoke, and wondered if she should have suggested finding somewhere more cheerful. But her two companions seemed happy enough.

‘Thank you both for all your help this term again,’ said Connie as they clinked glasses of wine. ‘I’m going to miss you.’ She thought for a moment. ‘But maybe we should meet up now and again, right here?’

Gill took an enormous slurp of her drink. ‘Great idea, Connie, but why won’t you be doing the classes any more?’

Connie shrugged. ‘I don’t want to commit myself to anything just at the moment. I’m getting itchy feet and I’m not sure I’ll want to stay in London.’

‘But where would you go?’ Maggie, as always, sounded anxious and tired, her skin pale against her faded once-red hair.

‘I’ve got some ideas but no definite plans as yet.’ And maybe, thought Connie, it was crazy to plan too far ahead when you were coming up to seventy. The last time she’d felt like this she’d left her husband of forty-one years. She had no regrets whatsoever, although it had taken her some time to recover from the resulting upheaval. Now that the unpleasantness of their bizarre uncoupling – and it was truly weird – had passed, the house had been sold and there was some money in the bank, she should really be looking to buy her own place back down in Sussex, near to the rest of her family. Time to be sensible again, perhaps? Oh God no, she thought. Not yet.

She knew very little about the other two. Gill, surely the epitome of an ancient Essex Girl, was divorced at least once, had six children, and still eyed every passing male with relish. And she knew even less about Maggie, other than that she lived with some dodgy bloke, had a son on the other side of the world, and never seemed particularly happy. But, against the odds, she’d become rather fond of them both. Connie had realised fairly early on that there was more to each of them than first impressions allowed.

Gill Riley fought against time, tooth (new, white and expensive) and nail (French manicured). ‘You ’ave ze ’ands of a woman ’alf your age,’ said Mimi at the nail bar as she glued the extensions into place. Mimi’s accent rarely slipped, although it was rumoured she originally hailed from Southend. Gill had been a type of model in her prime; not exactly Vogue, of course, but then she’d never had to do anything too saucy either, although she’d been asked to do so many times due to being exceptionally well endowed. More top shelf than top drawer.

Now, alone after two husbands and countless lovers, she mourned not only the passing of her youth but also of Harvey, her cat. He’d been her only true and constant companion for years and now he, too, had gone. Gill was, of course, invisible to men, as are all women over a certain age, and she was considerably over that certain age. And feeling lonely.

Nevertheless, she knew how important it was to stay looking good because you never knew just when he might show up. And she definitely wanted him to show up. But some of these guys online were a complete joke – or they might have been had Gill’s humour not begun to run dry, like everything else. She would be seventy next birthday, but she had no wish to celebrate that, thank you very much, since everyone except her six kids and their respective fathers thought she was only sixty. Well, she hoped they did. Blimey, her eldest, Marlene, at fifty-two, was a grandmother herself! They were scattered all over the place, the six of them, but threatening a mass get-together for her seventieth…

No, she certainly wouldn’t be having any of that.

Gill drained her glass.

‘I’m empty,’ she said, waving it in the air. ‘It’s my round! Who would like a top-up?’

Connie pushed her glass forward, and Maggie said, ‘Same again, but I’ll need to go to the loo to make some space!’

As Maggie washed her hands, she stared at her pale reflection in the age-spotted mirror and mourned the red-haired beauty of her youth. Where had ‘Miss Pride of the Clyde 1966’ gone? She might have been a model, she’d been told, if she’d only been six inches taller, but that was before Dave Holmes swept her off her eighteen-year-old feet with his good looks and gift of the gab. A shotgun wedding, they said. But in 1966 that’s what you did; no single mums getting council flats and handouts back then – not in her part of Glasgow at any rate.

She still hated removing her bra. Even after ten years she couldn’t suppress a shudder when she gazed at where her left breast used to be. She should probably have had reconstruction surgery, although she’d thought at her age it would hardly matter; but it obviously did matter to Ringer.

Ringer had come along three years after Dave’s fatal heart attack. He’d taken care of her and Alistair, her son, who was only five at the time. She’d adored him, so much so that she’d even agreed to come to London with him because that was where ‘it was all happening’, Ringer said. She never once asked where the money came from, because it was better really not to know, but she became an expert at providing believable alibis and hiding his hauls in all sorts of ridiculous places. Sometimes she forgot where she’d hidden them herself. Once she’d even made him turn off the water supply so she could fill the toilet cisterns with banknotes and, when the old bill came rummaging around, she prayed none of them would want a pee.

She lived well enough though. Ringer might not be the most generous of men but he’d got them a two-bedroom ground floor flat with a nice wee garden. But how many times had she dug up these flower borders over the years? When they’d been planting their annuals next door she’d been planting Ringer’s bags and boxes, and then covering over the disturbed earth with begonias, or dead leaves, depending on the season. Maggie loved flowers and would have liked a permanent display, but needs must.

Except that lately he’d been meaner than usual with his cash. And his affections.

A friend, Maureen, had seen him up west: ‘He’d got this blonde bimbo hanging on his arm and his every bloody word. Difficult to tell her age but a helluva lot younger than him – and us.’

Perhaps the blonde bimbo didn’t know Ringer had a partner back in the flat at Rotherhithe. Perhaps he’d told her he was single and, technically of course, he was. Either way it was time for Maggie to take stock.

She dried her hands and went back to join the other two.

Several glasses of wine later they agreed to meet up again just after Easter, ‘Right here: same time, same place.’

Connie walked home along the Thames Path, past the ruins of King Edward’s manor house, now no more than a series of small walls. She was fond of that particular spot and stopped to gaze out across the river and take stock of her thoughts. She felt no regrets at abandoning a stagnant marriage or the ‘retirement’ bungalow she’d never been able to love. She was now ensconced in her elder daughter’s stylish London apartment, Diana having moved in with her ‘boyfriend’. That’s if you could call a man of nearly fifty a boyfriend, Connie thought. ‘Partner’ was probably more correct these days, she supposed, although she still associated the word with ‘take your partners for a quickstep’ at the local Palais. All history now, like her marriage. Anyway, ‘lover’ was a much nicer word.

What Connie hadn’t realised was that she might sometimes be lonely, that she might miss her children and grandchildren down in Sussex. They’d all adapted to life without her, of course, which had hurt a little more than she’d anticipated. And she missed her friends too, especially Sue and their shopping trips to Brighton. And their endless discussions over countless bottles of wine about how they’d like to leave their boring husbands and demanding families. Well, Connie had done it, while Sue was still there.

Connie often went down to Sussex, and of course they all came up to London, but there were still some lonely hours to fill when she felt an unexpected emptiness and lack of purpose. Giving the flower-arranging classes helped, but what had helped more than anything was the research into her family history. And that had come about as a result of The Box making its appearance. The Box’s contents made Connie feel as if she was reclaiming some part of herself that she’d never known she had.

The Box. Why on earth had her aunt never produced it? Didn’t she know it was there? Because The Box was only discovered when Connie’s cousin was clearing the attic shortly after Aunt Lorna, aged ninety-nine, had finally breathed her last.

‘This stuff must be for you,’ Judith said, as Connie was about to leave after the funeral tea.

She handed over an old metal biscuit box rusting at the edges, ecru-coloured with romantic scenes of notable Scottish castles on each corner, with ‘Crawford’s Biscuits’, ‘From Scotland’ and ‘For Afternoon Tea’ displayed on three banners in the centre of the lid. And inside – along with papers yellowed at the edges, letters in faded italic script and old sepia photographs – was the marriage certificate. The marriage between one Robert Cox and one Maria Martilucci of Amalfi, Italy. The letters were in Italian and, as far as she could make out, from Maria’s parents. She’d need to find someone to translate these for her, which would not be easy as the ink had faded from its original colour to a pale yellow and, in places, was indecipherable.

The photos, too, were faded. A young girl with long black hair, all dressed in white like a bride. Maria’s first Mass, perhaps? And others of stiffly posed adults beside a large house, tiled and shuttered Italian-style. And a panorama of the sea, which was certainly nowhere around Newcastle. There was a man in some sort of uniform.

As well as the photographs there was a topaz ring, which Connie was now wearing on the ring finger of her right hand.

Connie’s Uncle Bill, her mother’s brother, and his wife, Aunt Lorna, had taken over when Connie was orphaned at five years old. They’d had four children of their own, so maybe The Box wasn’t exactly a priority. ‘Stick it in the attic for now,’ they’d probably said.

As a result, Connie knew nothing about any box, or about her father’s side of the family, other than that he had been an only child, had hailed from Newcastle, and appeared to have no living relatives.

And now, sixty-five years later, The Box had reappeared and Connie had discovered the marriage certificate and her Italian grandmother. An Italian grandmother! And that’s when the ideas began to form in her head, ideas that she’d have time to pursue now that the floristry classes were coming to an end. She’d have time to dig deeper into her family’s past; this Italian side of the family about which she knew nothing.

Connie had sold her car when she moved from Sussex. No need for a car in London, of course, and nowhere to park it, but she missed driving. Perhaps she should think about buying another one and driving down to Italy? She wouldn’t be thinking about going to Italy at all if it wasn’t for The Box. But, once she discovered what was in it, she couldn’t leave it unexplored, so she’d have to go to Italy. But how long would that take and would she have the courage to do it? She supposed she could take her time, all summer if she wanted. The idea had germinated and started to grow.

Then, as she sat in the train heading towards Sussex for the weekend with Nick and the family, it suddenly screeched to a halt. ‘Sorry, ladies and gentlemen.’ The guard’s voice could just about be heard through the fuzzy PA system. ‘We’ve had to stop for a fallen branch across the line. We may be here a few minutes while they clear the obstruction.’ There was a general moaning all round and Connie looked out of the window hoping to see the offending branch, but instead became aware for the first time of an enormous caravan dealership that bordered the railway line. She’d never noticed it before but on this occasion, the train being stationary, she was able to read the large banner which proclaimed: ‘Special Deal on Motor Homes!’ An omen, perhaps? Could she drive a motor home? No, of course not! Forget it!

But then again…

On one of her visits to Sussex, Connie told her son about her findings in The Box. Nick knew, as they all did, that she’d been orphaned when tiny and so knew precious little about her father’s side of the family. At first Nick had seemed sceptical, unconvinced that the contents of The Box would lead anywhere. But she knew that he, more than the others, worried about her being alone in London. And he admitted to being a little concerned as to what she might get up to next.

‘Surely you must have known about some of this before?’

‘I only knew her name was Maria because I’d visited their grave up in Newcastle; Robert and Maria they were called. I never met them because they both died around the time I was born. The only information I’ve got really was from an old neighbour I tracked down when I was up there years ago. He told me my granddad had had a little market stall, somewhere near the docks.’ Connie remembered the old boy who was only too eager to tell her about the flour, rice, spices and ‘funny foreign things’ her grandfather had had for sale. ‘See,’ he’d said, ‘there were lots of foreigners around the docks in them days looking for olives and funny stuff like that.’ But he’d made no mention of a foreign wife, funny or otherwise.

‘And what I’ve discovered from The Box,’ Connie went on, ‘is that my enterprising grandfather had married one Maria Martilucci from somewhere near Amalfi in Italy! I’d love to go there and see if I can find some cousins. Wouldn’t that be thrilling? Do you remember we drove along the Amalfi Coast years ago when you were tiny? So beautiful!’

‘Mum,’ Nick said with exaggerated patience. ‘You do get carried away sometimes. After all, there must be millions of Martiluccis in Italy and how are you ever going to find out if any are related?’

Connie had little idea, but replied, ‘I’d have a lot more chance of finding out in Italy than I ever would here.’ And she was fascinated by the idea that some Latin blood might be coursing around in her veins. Surveying her grey-green eyes and less-than-lush eyelashes in her hand mirror, Connie felt a desperate need for some of that traditional Latin lusciousness: the dark eyes, the lustrous lashes and that thick dark hair which turned an interesting steel colour with maturity. Well, at least she had thick hair, although sometimes she had difficulty in remembering what colour it had once been underneath the highlights and lowlights. British brown, if she remembered rightly.

For the first time in decades, after forty-one years of marriage and four children, Connie McColl was free to do as she wished. She went out to Waterstones and bought a Teach Yourself Italian book and CD. And then wondered if easyJet or Ryanair flew to Naples. That would be the sensible way to get there. She listened to her Andrea Bocelli CD while pondering the possibilities. Could this be another adventure?

Connie spent Easter with Nick, Tess and the boys. And she spent a lot of that time daydreaming.

A week later Connie asked, ‘Did you do anything nice over Easter?’ as the three women settled themselves at a non-wobbly table near the pub window. It was almost warm enough to sit outside.

‘Nah,’ said Gill. ‘Stayed with my daughter, the one who lives near Margate. Screaming kids everywhere.’ She was wearing a too-short skirt and shoes with what looked like four-inch heels.

Maggie took a gulp of her wine. ‘No, we didn’t do much either. Ringer was out on business a lot of the time.’ In contrast, Maggie was wearing jeans and trainers, topped with a purple fleece that drained her of what little colour she had.

Out on business, at Easter? Not for the first time Connie wondered about Maggie’s partner and exactly what business he was in.

‘What about you, Connie?’

‘Oh, the usual. A couple of days with Nick and his family, then a day or two with my younger daughter, Lou, and her family. Love them all to bits, but exhausting.’ And it was true. In the couple of years she’d been living in London she had definitely become much more tired much more easily. She didn’t relish coming up to seventy, but there it was and, as they say, better than the alternative.

Maggie stared gloomily out of the window. ‘I think I’m needing to shake up my life.’

The other two looked at her questioningly.

‘What’s wrong with your life then, Maggie?’ Gill asked.

Maggie shrugged. ‘It would appear I’m past my sell-by date. Being replaced by a newer model.’

‘Oh, Maggie!’ Connie and Gill spoke in unison.

Maggie took another large slurp. ‘Yeah, well.’

‘Men!’ exclaimed Connie. ‘Maybe it’s time you found yourself a younger model too.’

‘A toy-boy,’ said Gill, ‘but don’t hold your breath, Maggie, ’cos I’ve been looking for years.’

‘Ringer’s five years younger than me anyway,’ Maggie said, to no one in particular.

‘Why’s he called Ringer?’ Gill asked.

‘Well, he’s William really, but his surname’s Bell. So, Ringer Bell. That’s another story. Not that he does much bell-ringing.’ Maggie sniggered at the thought.

‘Hardly a campanologist then,’ scoffed Gill.

‘More of an escapologist,’ Maggie said drily.

Connie and Gill exchanged glances, both too embarrassed to ask Maggie exactly what she meant. Connie stared out of the window where an elderly couple were seated at a table on the pavement; he hidden from view by his outstretched edition of the Sun, while she gazed sadly into space. Marriage. Some marriages. Most marriages? Connie’s marriage had been similar, jogging along from years of habit. (‘Looks like rain, doesn’t it?’ ‘Will you be golfing today, dear?’)

‘You’re on your own, aren’t you, Connie?’ Maggie asked.

‘Yes, divorced. Just got some money from the sale of the house and from a small inheritance but haven’t decided what to do with it yet. I should, of course, be looking at somewhere to buy instead of paying rent.’ Connie shrugged. ‘I really must make my mind up what I’m going to do.’

‘Surely,’ said Gill, ‘you can do anything you fancy.’

Connie grinned. ‘You know what, Gill? You’re absolutely right!’ She looked out at the rain drumming against the window.

And what I fancy, Connie thought, is some sunshine.

Connie had finally succumbed to her urge and taken herself to have a wander round Get Moving, the motorhome dealership she’d spotted on the day the tree had shed its branch across the train line. She hadn’t looked inside any sort of caravan for years, not since the newlywed Nick and Tess had taken themselves off to Spain in an ancient camper van nearly ten years ago.

‘You’ll hardly be able to stand up or move in that thing,’ she’d remarked to her son, six foot two in his stockinged feet, and his well-upholstered wife.

‘We plan to be lying down most of the time,’ Nick had replied with a glint in his eye.

But these luxurious models were something else. Connie was bowled over by the clever designs, the proper kitchens, loos, showers and beds that popped out of nowhere. You could almost . . .

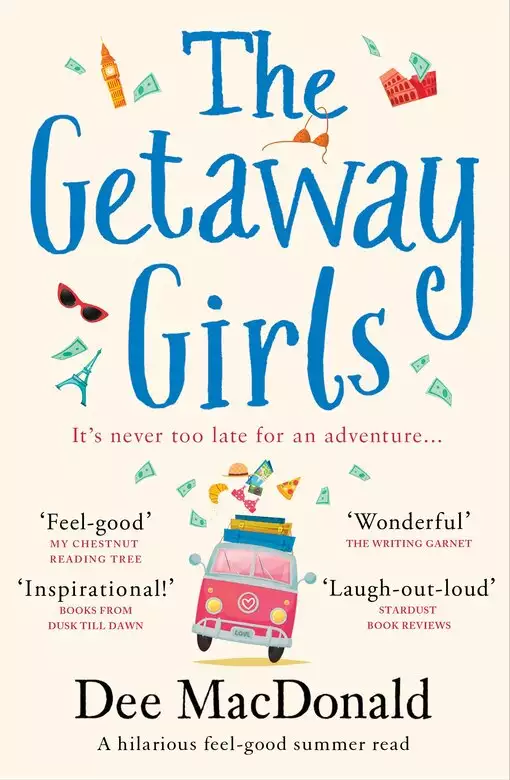

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved