- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

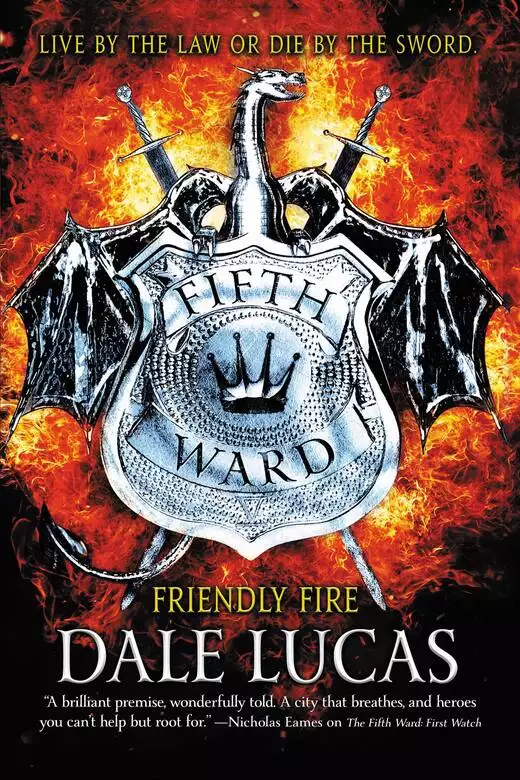

Synopsis

'A brilliant premise, wonderfully told. A city that breathes, and heroes you can't help but root for' Nicholas Eames on The Fifth Ward: First Watch

Humans, orcs, mages, elves and dwarves all jostle for success and survival in the cramped quarters of the city of Yenara, while understaffed Watch Wardens struggle to keep its citizens in line.

In the most dangerous district in the city, Rem and Torval have been perfecting their good cop, bad cop routine. But when a perplexing case of arson leads to a series of gruesome murders, the two partners must challenge their own assumptions and loyalties if they are to wrest justice from the chaos and keep their ward from tearing itself apart.

Release date: August 7, 2018

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 496

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Fifth Ward, The: Friendly Fire

Dale Lucas

Rem struggled to regain himself—to wipe the mud from his eyes, to draw breath, to stand—despite pains both broad and acute from head to toe. He heard the raucous clip-clopping of the bulky draft horse’s shod hooves galloping along Fishmonger’s Row, the speeding cart rumbling rowdily behind it.

“Are you just going to lay there?” the piss-monger brayed, his oafish son at his elbow. “That thieving swine’s getting away!”

I know, Rem wanted to say. That’s why I was in the mud, you plank. Did you not see me on the cart’s running board? Trying to clamber on? Narrowly avoiding those enormous wheels as I fell?

But he knew it would do no good. Thus Rem ignored the malodorous nightman, found his feet, and reeled out into the middle of the wide, cobbled street. His quarry raced into the distance, heading east. If the fleeing rogue kept the cart on cobbled streets—to keep from bogging in the mud—his path would have to loop back toward the river and follow it for a short length before he could finally wend eastward again, toward the city gate. If he reached the gates with enough speed behind him, not even the city guards could hinder his escape. Rem knew for a fact that the lazy bastards were in the habit of guarding the city gates at night—but rarely closing them.

Rem leapt into a desperate sprint in the cart’s wake, his mind formulating something like a plan, fuzzy though it might be. Ahead, beyond the rattling pisswain, something caught his eye.

A short, stocky form trotted out of a side alley a block on from the rushing wagon. It was his partner, the dwarf Torval, hurrying back onto the main drag from the side street he’d been searching.

And he was rushing right into the cart’s path!

Rem had time to shout Torval’s name once—just once—before the hurtling cart ran over his stocky dwarven partner, losing no momentum as it jounced down the length of Fishmonger’s Row.

Rem screamed something that was no longer Torval’s name—just a howl of disbelief, terror, unbridled rage. He sprinted in the wake of the cart while the thief whipped the draft horse hard, opening the distance between them second by second. Something in Rem relented. There was no way he could catch that cart, but at any moment—any horrible, soon-to-arrive moment—he’d see Torval’s crushed and twisted dwarven corpse come rolling out from underneath the damned thing.

Any moment now.

Any moment …

Losing speed, Rem squinted, trying to get a good look at the cart in the dim moon- and starlight supplemented by the few lit post lamps lining the boulevard. He blinked. Did his eyes deceive him? Could it be?

There was Torval, still very much alive, clinging to the axle assembly on the underside of the cart. The whole bloody thing must have passed right over the old stump, the horse’s hooves somehow missing him in its headlong dash.

Rem slowed to a trot, knowing that he could not catch the cart, no matter how fast he ran … and curious as to just what his seemingly unkillable partner was up to.

In a series of quick, jerky movements, Torval worked his way to the rear of the cart. Eager to get up off the cobbled street, he clawed for purchase. As the cart rolled on, Torval dragged himself, hand over hand—precariously, laboriously—into the open rear bed of the cart as it jounced over the cobbles on Fishmonger’s Row.

“You’ve got to be fucking kidding,” Rem muttered as he jogged.

But there was no jest to be found. He saw clearly in the dim glow of the post lamps and windows lining the street that Torval had clawed his way up onto the cart bed and now sought a clear path forward among the stout, sloshing jars of piss and shit that stood between him and the thief on the driver’s bench. Thus far the thief hadn’t looked over his shoulder even once. He just sat there, hunched on the driver’s bench, whipping the horse on, keen to leave Rem well in his wake.

Rem gave up. He had to take a moment—just a moment—to regain himself. He fell to his knees and drank in the night air like sweet, cool water in the midst of a vast desert. His lungs burned. His legs felt like warmed-over beef fat.

Get up, a voice inside him said. Your partner needs you.

Rem raised his eyes. The cart was just veering right, out of sight, bending southerly now at the beginning of that long loop that would take it back toward the river on cobbled streets before it turned once more eastward, onto a long, straight course toward the city gate.

Rem considered where he was, where the cart was headed, what pathways were available to him … and then realized that there was a route capable of leading him straight into the path of the cart’s flight. If he hurried. If he could only find …

He saw what he required not a hundred yards from him: a livery stable, all closed up for the night.

“Aemon wept,” he cursed, then struggled to his feet and ran a little farther.

He managed to bridle his chosen mount quickly, but couldn’t waste time on a saddle … nor on making the stabler aware that one of his stock had been commandeered by a desperate watchwarden.

Before the present mess with the piss cart, the evening had been lovely: deep into the month of Haniss, creeping toward the solstice, the nights in Yenara utterly devoid of the fog that so often shrouded the city in a choking diaphanous haze. No, that night had been like many of late: keen and crisp, clear as glass, the heavens strewn with a million tiny pinpricks of firelight winking like diamonds thrown carelessly upon a jeweler’s black velvet counting cloth, the moon fat as a silver pie, not a cloud to mar the majestic, vertiginous view.

Rem and Torval had been on patrol along Fishmonger’s Row, the long, wide boulevard that bisected the little harborside peninsula known as Gaunt’s Point. When they heard the hue and cry, the two set aside their heated exchange—an in-depth debate on which bird tasted best from a brazier of coals, pigeon or gull—and broke into a dead run toward the disturbance.

The cries led them from the main thoroughfare into a maze of side streets nearer the waterfront and to a boxy dwelling tucked away between a tavern and a seamen’s hostel. It was a home for the orphaned or abandoned children of mariners and fishermen, run by a kindly middle-aged widow named Dorma. Smoke and flames poured from its opened lower windows while local fire brigade volunteers shuttled in water to try to douse it. A few dozen people milled at the edges of the courtyard, coughing smoke from their lungs, most of them women and children. Their injuries seemed superficial for the most part—bruises, scrapes, some soot stains, and a lot of coughing—but there were two or three little ones struggling mightily for breath. The sight immediately turned Rem’s stomach.

Dorma stood in the middle of the street, soot streaked, graying hair a tangled mess, banging two cookpots together and shouting.

“Here we are,” Torval spat. “Hang that racket.”

Dorma stopped beating the pots together, dropped them, and stepped forward. To Rem’s great surprise, she laid hands on Torval, a move that—had she been a man—would probably have earned her broken fingers or a sprained wrist.

“They’ve taken her! There’s no time to lose!”

“Taken who?” Rem asked, as softly as he could.

“Iesta!” the woman said, as if it were the clearest fact in all the world. “Recover her, I beg you! No reward shall be too great if you can return her!”

Torval gently shrugged off the woman’s grip. “Who’s this Iesta? One of the children? Is she kidnapped?”

“No,” Rem said, still not sure why Dorma was in such a twist, “Iesta’s one of the goddesses of the Panoply. Empress of the Abandoned. Patron of beggars, orphans, and mendicants, correct?”

“Precisely!” the woman said. “And she’s gone! They’ve taken her!”

“Hold on,” Torval said. “You’re telling me your home is burning and you’ve got hurt children all about and you’re in a twist about a bloody idol from your house shrine?”

“The idol’s hollow!” Dorma shouted, then bent close to add, “All our savings are inside it. Without that coin—”

Ah, there it was. The fire was not just some accidental blaze, but a distraction to cover a thief’s flight.

Rem nodded and clapped Torval on the shoulder; time to go to work. “See to the children,” he told Dorma. “We’ll have Iesta back by sunrise.”

She gave them a hurried description of the idol—a heavy, awkward sculpture of half-wrought old jewelry and tinkers’ castoffs, about the size of a well-fed toddler—and then the two were off.

“Stealing a household god,” Rem huffed as they ran, the cold night air burning his lungs. “Shameful. Who purloins a god, anyway?”

Torval took a sudden left down a dark, narrow alley, and Rem very nearly overshot and lost him altogether. Torval barked back over his shoulder, “Where there’s need, there’s no decency,” he said.

They broke out of the alleyway onto Fishmonger’s Row, the only cobbled street in all of Gaunt’s Point, running nearly its length. Torval scrambled to a halt and scanned the area. Rem skidded to a stop beside Torval and struggled to catch his breath. Between the late hour and the bitter cold, foot traffic was light, but there were a few shadowy figures scattered along the avenue, reeling their way home from a drink or trudging off to a midnight shift in some warehouse or mill on the riverbank.

“What are we looking for?” Rem asked between great gulps of air.

“Consider the idol,” Torval said. “An awkward size and shape. Probably heavy, too. To move such a thing, our thief would have to go by horseback or cart sooner or later.”

“Simple enough,” Rem huffed. “Carts and horses are forbidden on the streets from dusk ’til dawn. He’d stick out like a sore thumb. He could just be holed up, waiting for morning—”

“Not likely,” Torval said. “He had to know that if they raised an alarm, there’d be watchwardens swarming the Point in no time. His only hope for escape is speed and distance. And if he’s going to gain ground, he needs hooves or wheels, and fast.”

“It’s a fool’s move,” Rem pressed. “Knowing that he’d be caught so easily, on a horse or a wagon, out in the open, when there are none about—”

Torval turned to Rem and eyed him askance. “Except for …?”

Rem suddenly realized what Torval was getting at. “Honeywagons,” Rem said.

“Honeywagons,” Torval repeated, proud that his protégé had followed his lead.

The only beast-drawn carts allowed to move through the streets at night were those of the nightmen, known colloquially as gong farmers, slop-brokers, or piss-mongers—men who contracted with the wards and their neighborhood councils to collect urine and excrement from the waste barrels that haunted the darkest downstairs corners of most tenements and boardinghouses. They’d crawl slowly up and down the side streets of Yenara all night long in their horse- or ox-drawn slop wains, hauling out those stinking barrels wherein Yenara’s good citizens emptied their chamber pots, transferring all that stewing egesta into great clay jars that were then delivered to the city’s tanneries for use in industrial leather curing, or beyond the walls to be used as fertilizer for nearby farms. Once or twice Rem and Torval had broken up brawls between competing slop-mongers, as one might try to horn in on another’s contracted routes to illicitly top off his jars. Tanners and farmers paid good money for all that piss and shit, after all, and very few people lined up for the dubious honor of collecting it. Generally, though, the wardwatch were aware of the progress of the honeywagons only peripherally, the sight, sound, and smell of them a barely noticed but prosaic element of Yenara’s everyday life—best ignored, if not forgotten.

“So, split up?” Rem asked. “I’ll head west, you east.”

Torval nodded. “Just so. Check any haul you find. Make any piss-mongers you meet aware of who and what we’re looking for. Could be, if they’re on their guard, our thief won’t manage to so easily overtake them.”

They split up then. Three blocks along, down a side alley, Rem found just what he sought: two human silhouettes beside a large horse-drawn wain parked in the lee of a three-story tenement. Rem set off down the length of the dark side street, the cart only a short block beyond the main road.

“You there!” Rem cried. “Step away from that cart and stand where you are! Wardwatch!”

The two silhouettes froze and seemed to study him. The shorter of the two clapped the larger one on the shoulder. The tall one bent to his labors again, while the other advanced toward Rem.

“I said stand where you are!” Rem shouted. “Throw up your hands!” Slowing now, he drew his sword, the blade hissing as it slid from its scabbard, keen edges glinting a little in the dim lamplight of the gloomy street. So armed, he slowed his approach just ten feet from the cart and its reeking contents, face-to-face with the big liver-colored draft horse hitched to the wain’s traces. The shorter and thicker of the two men stepped between Rem and the cart, then raised something: a wooden ax handle with an improvised lumpy iron crown.

“My permits are paid,” the fellow spat, shaking his bludgeon. “If you’re from Toomey’s camp, trying to jack this load, you’ll find my boy and me hard contests, indeed!”

The lug at the rear of the cart lifted his head again. “Need help, Da?”

“Bend to your work, boy. I can handle this one.”

Rem reached into his greatcoat—standard issue for all watchwardens in these colder months—and drew out his lead badge on its leather string. “I’m wardwatch, sir,” Rem said, showing it plainly. “You have my word. We’re just looking for—”

“Steady on, old-timer,” the broad, muscled boy at the rear of the cart said.

It took Rem a moment to realize that the boy wasn’t talking to him, nor to his own father. He was instead addressing a new arrival on the scene—a bent old man with what looked like a horribly hunched back shuffling up the street toward the cart. The old man leaned on a crooked stick to support himself as he made slow, crabwise progress along the muddy street. It seemed that the boy had noticed the old fellow’s struggling, shuffling gait, for he now moved toward him, eager to help him along.

“Myrick,” the father said over his shoulder, never taking his eyes off Rem, “get back on those slop jars!”

“Just a moment, Da,” the boy said. “This old duffer just about stumbled right over them.”

The old man suddenly swatted the young man’s shins with his walking stick. The young piss collector bent, crying out. The walking stick rose in the air, then thumped him hard on his melon head. Down the lad went into the mud, moaning. The piss-monger turned to see what troubled his boy.

Rem stared for a moment, trying to puzzle it out: Why thump the boy like that? He’d only been trying to help.

Then something strange happened. The bent old man stood upright, spun round—putting his back to the cart—and yanked at a knot on his tunic. Something heavy—the very hump on his back—dropped with a thud into the cart bed. Suddenly Rem understood.

This was their thief. That hump on his back had been the idol itself, tied beneath his cloak. Now the thief had dumped his cargo and was climbing into the honeywagon.

Rem shot forward as the thief scurried up the length of the cart toward the driver’s bench. Just as Rem reached the middle of the wagon and leapt awkwardly onto the running board, planning to clamber over the cart’s plank frame in a clumsy effort to cut off his suspect, the thief danced nimbly past him, thumped down onto the sprung driver’s bench, and snatched up the reins of the draft horse. There was a snap. The horse jerked in its traces, and the cart was under way.

Rem clung to the side, one boot on the running board, another flailing through space. He had one good handgrip on the rail of the cart bed, but holding his sword in his other hand meant he could not gain purchase without first dropping his weapon. He was trying to decide what to do about that when the thief rose up in the driver’s seat and, without loosing the reins, turned and gave the slop jar nearest the outside rail—nearest Rem—a stout kick. Terrified of getting a face full of piss and excrement, Rem threw himself off the trundling cart.

He fell clear of the wagon and hit the mud with stunning force. Somewhere he heard the shattering of a clay jar, and the world was suddenly rich with the smell of ordure—but none of it, thank all the gods of the ancients and the Panoply, had landed on him.

“Are you just going to lay there?” the piss-monger then brayed from above him, his oafish son at his elbow. “That thieving swine’s getting away!”

But that was all behind him now, literally, for Rem was galloping along at a foolhardy pace, bent low over his stolen horse as he squeezed its foaming flanks between aching knees and whipped it with reins gripped in sweating hands. Beast and rider barreled on past drunken laborers reeling out of cellar stairwells, barking house mutts, corner congregations of underfed cats, and at least one stumbling, bleary-eyed molly who stank of witchweed and cheap brandy. Less than a mile due west, in the city center, the Brother of the Watch at the great tower of Aemon began his dutiful tolling of the hourly bell, low and sonorous. Rem’s heart beat a syncopated tattoo after each plaintive knell. He counted three.

His lungs burned. His thigh muscles screamed. He’d thought running toward his intended rendezvous would exhaust him, yet keeping himself upright on an unsaddled horse—especially one weaving through narrow streets at such a breakneck pace—was no mean feat. But Torval needed him. If Rem didn’t make the bridge he sought in time …

There. Up ahead. He saw two familiar high-rises—each towering a dizzying seven stories in the air above him. Those twin blocks marked the entrance to a steep flight of stairs that would put him on a footbridge that arced over Eastgate, the wide cobbled boulevard that the fleeing thief would eventually careen onto. Rem imagined he heard the rumbling rattle of the cart hurtling nearer even now, but knew that it was probably just his own mount’s hooves thumping on the street mud.

Rem reined in the mare and she balked, spinning in the street, screaming in protest. He hated to so mistreat her, but he had no time for niceties. Without bothering to hobble or tie her, he swung himself down from his perch, mounted the stairs that rose between the tenements, and bounded upward toward the apex of the bridge. He’d made good time on horseback. If he could put himself in the center of that bridge as the thief’s plunging cart passed beneath him …

He could … what? Leap? Try to land in the shit-and-piss-jar-crammed conveyance?

He didn’t really have a plan. Probably wouldn’t have time to formulate one, either.

Plans? Fah! Torval would’ve scoffed. Who needs ’em?

Rem pounded onto the arcing stone bridge and slowed at its center. He was facing west now, along the gentle curve of Eastgate Street as it bent toward the Embrys River.

There, a thousand yards away and closing, was his quarry. The big horse yoked to the cart galloped flat out now—faster than good sense or safety should allow, hot breath billowing in torrid clouds as steam curled in tendrils off the animal’s foam-flecked coat. The clatter of its hooves on the cobbles was cacophonous, rising toward deafening as it rumbled closer and closer to where Rem stood on the bridge.

Rem blinked, trying to get a good look at what was happening on the moving cart.

The driver’s bench was empty. Two figures—the thief and Torval—grappled, swayed and jerked about in the cargo bed. Only three of the slop jars remained—the rest casualties of the hand-to-hand struggle, no doubt.

No one was driving the cart, meaning the horse’s reins would have fallen into the traces. Thief or no thief, a speeding cart behind an uncontrolled horse could spell disaster, not only for its occupants, but for anyone unlucky enough to stumble into its path.

Cack.

Rem mounted the stone railing. He watched the cart rattle nearer and nearer, making an unholy racket as it did so. More than a few of the residents and business-folk lining Eastgate leaned from their windows or peered cautiously from their doorways in answer to the tumult, staring, calling down into the streets to warn the few early-morning strollers or call for the wardwatch.

The cart was almost beneath him. Every tiny particle of Rem’s being screamed that he was making a terrible mistake—but Rem refused to listen. How high was he up here? Twenty feet? Thirty? When he looked straight down at the street below, it could have been a hundred. He said a short, silent prayer to whatever gods still might humor him, then leapt.

For just a moment it felt as if he were going nowhere at all—floating, not falling. Everything he saw became crystal clear and languid. He saw Torval and the thief grappling viciously in the cart bed—his partner’s bald pate and the dark-blue tattoos on it clear in the murky light, the thief’s own mop of unruly brown hair trailing a single long, tight braid at the base of his skull. It seemed to take such an impossibly long time that Rem feared the rushing cart would pass too quickly beneath him, that he’d miss it entirely.

Then there was a rush of wind, a strange feeling in his nethers, and he was on top of them. The three—Rem, Torval, the thief—tumbled backward in a tangle of arms and legs, spittle and curses and rancid breath. For one fleeting moment Rem felt Torval’s short, thick legs plant themselves in the cart bed to forestall their group plunge backward. Then the three of them—as a single organism—were thrown out of the cart into empty air.

Torval and the thief hit the cobbles first. Rem landed on top, but their momentum threw them into a wild roll along the street. Rem’s world was upended—he on the bottom, they on top, he on top, they on the bottom, and—Gods, those cobbles hurt!—they kept on rolling, and—Blast! Torval punched him in the flank, thinking his body was the thief’s—Son of a—then their happy little triptych flew apart and—Snikt! Did someone just draw a knife?—thankfully, blessedly, their roll became a played-out wobble. Finally they were at rest. Rem lay sprawled on the cobbles, belly-down, cheek against the cold, filthy paving.

“Ow,” he muttered, then lifted his head.

Ahead of them—far ahead of them—the horse drifted toward the sidewalk. The beast’s hooves left the cobbles and hit the flagstones. The cart followed, jouncing sideways, then leapt up from the flags onto the lowest of a broad series of steps leading up to the entrance of a great stone building. The steps turned the cart up onto its street-side wheels. The horse bucked against its twisting harness and the uncomfortable shove of the wooden shafts binding it. Then the cart, already half-upended, somersaulted sideways. As Rem watched, the horse’s harness and shafts tore loose. The cart vaulted into the street and came to rest, its broken wheels spinning in the air, the open cargo bed smashed against the cobbles. The last three slop jars had shattered, spilling their stinking contents across the breadth of Eastgate, nearby witnesses shrinking from the stench and yanking their tunics up over their noses. The horse kept running, faster and faster now that it was free, on along Eastgate and out of sight.

“Watch it, lad!” Torval shouted, and Rem threw himself over onto his back just in time to see the thief plunging toward him, a shiny, sharp dagger in his left hand. As the thief bent over him, Rem planted one foot in his would-be assailant’s gut and shoved as hard as he could. The thief flew backward, right into Torval’s waiting arms. As Rem scurried to his feet, he saw Torval’s long, muscular arms curl up beneath the thief’s armpits. To Rem’s great astonishment, their quarry was a very young man of decidedly ordinary appearance and dress. Had Rem seen him on the street, he wouldn’t have pegged him as the sort to lead them on such a wild, wearying chase.

Torval’s thick, square hands locked behind the boy’s head, and his arms flexed. The boy found himself bent halfway over backward, head shoved forward, arms raised comically at his sides. Torval shook the lad and the dagger clattered to the ground.

Rem needed no invitation and lunged forward to hook his left fist into the young man’s belly. The boy groaned and bent double in Torval’s grip. The dwarf, seeing his prey tenderized, released his hold, and the young thief hit the ground in a bloody heap. He was gasping for breath, moaning, but he made no attempt to rise.

“Stay down,” Rem said. He brandished his sheathed sword so that the bent-double thief could see it. “If you move again, I’ll take it as resistance, and I’ll run you through without a second thought. Do you understand?”

The thief nodded weakly. He couldn’t seem to find any words. Rem, gasping for breath himself, knew exactly how he felt. Studying the boy now, seeing how young he was—fifteen, sixteen at most—Rem almost felt sorry for him … almost regretted having hit him so hard after Torval had him subdued. Then he remembered what they’d just survived and shoved his pity aside. The boy might have daring and a mountain of fight in him, but he didn’t have the sense the gods gave a goat.

Torval stood for a moment, huffing and puffing in the cold night air, an angry (if diminutive) bull not quite sure if it should charge or beg off. Finally the dwarf shook all over—a strange gesture, Rem thought, almost as if Torval were trying to wriggle the fury out of himself. Then, seemingly calm, Torval turned to his partner.

Now Rem felt even worse. He’d hit the boy in anger and Torval hadn’t. How dare the old stump choose that moment to show how much self-control he could exercise!

“Did my eyes not deceive me?” Torval asked, sounding more angry than pleased. “Did you not just leap off that bridge back there into our speeding cart?”

Rem nodded, quite pleased with himself. “I surely did. You’re welcome.”

Torval, to his great surprise, gave him an angry shove. “You daft twat! You could have killed yourself! Or me!”

Rem blinked. “Well, then, old stump, next time I’ll just let the cart man drive away with you! Do you have any idea what I went through just trying to get here and head the two of you off?”

“I had him!” Torval growled. “I was an inch away from subduing him when—”

“He pulled a knife!” Rem shouted back. “I suppose you were ready for that, were you?”

“It was sloppy!” Torval sputtered. “Sloppy and reckless and foolish and—”

“And lifesaving?” Rem offered.

“Whose life?” Torval countered. “You could’ve missed us entirely and cracked your skull like a morning egg! And then where would I be? Another dead partner on my conscience! Never again, boy—do you understand me?”

Rem was about to respond, but Torval gave a disgusted wave of his arms, spun away, and marched up the street toward the wreckage of the pisswain. He shoved through all the lookie-loos now crowding around the mess, and Rem lost sight of him.

Rem stood beside their sprawled, groaning detainee, feeling both infuriated and humiliated. He’d just been trying to help. Was Torval truly angry with him for that?

The boy thief suddenly tried to skitter to his feet and flee. It was a fast, unexpected move—clearly planned through several minutes of feigned injury. Luckily, Rem managed to snatch at the boy’s tunic and throw him back to the ground. Once he had him down, he knelt on his back, snatched a length of double-looped rope from his belt, and tied the boy’s hands behind him.

“What part of stay down escapes your understanding?” Rem asked as he yanked the knots tight. He stood and surveyed his work. The boy flopped on his belly, but his hands were bound tight behind him now. He wouldn’t be rising anytime soon.

Torval trudged back toward them. He carried the stolen idol in his arms, cradled like a baby. It was an ugly thing, vaguely anthropomorphic, with a too-large face and too-short arms and legs and almost no torso, forged from a vast and varied coterie of costume jewels, bangles, torques, rings, and varied metal chains, none of quality, all melted toward viscosity and then pressed together by hammer and tongs into a bizarre and almost laughable approximation of a human figure.

This was what Dorma and her orphans paid their obsequies to and submitted their prayers to in their cramped little hostel. What Rem and Torval had almost died for. Though Rem knew that the idol contained a treasure of great importance—the whole savings of that orphanage, its only bulwark against poverty, dissolution, and destitute despair—it still made his stomach turn a little. Despite the blessing it held within, the idol itself was ugly and absurd.

Torval studied their prize and offered an assessment. “Pitiful, isn’t it?”

Rem nodded. He felt a crooked smile creeping onto his sweat-cooled face. “People put their faith in the strangest of things, don’t they?”

To his relief a similar bent smile bloomed on Torval’s broad, flat mug as well. “They do at that,” the dwarf said. His eyes narrowed, but his

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...