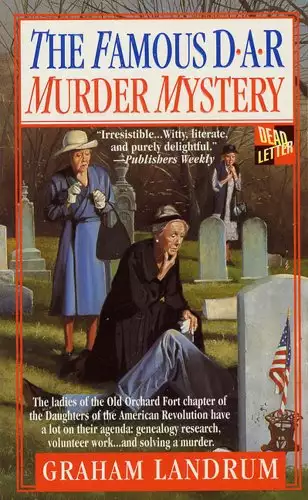

The Famous DAR Murder Mystery

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

The search for the grave of a Revolutionary War soldier takes a bizarre turn when four members of the Old Orchard Fort chapter of Daughters of the American Revolution stumble on a modern-day corpse. Though the sheriff dismisses the body as a transient battered in a drunken brawl, one of the ladies, organist Helen Delaporte, has other ideas. First, there are the victim's finely manicured hands...and then there is the map dropped at the scene of the crime.

Soon the D.A.R. members, including feisty, eighty-six-year-old Harriet Bushrow, are rebels with a cause, mounting an investigation of their own. Of course, when the press catches wind of it, they go to town. The coveted publicity for their chapter sets the ladies reveling...until Helen's windshield is showered with bullets...and it's clear that their new pet project could spell deadly ends for them all.

Told in the alternating voices of chapter members and other colorful characters, Graham Landrum's stunning novel is the first in a delightful series narrated by members of the community of Borderville (smack on the Virginia-Tennessee line).

Release date: April 1, 2011

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 198

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Famous DAR Murder Mystery

Graham Landrum

BROWN SPRING AND WHAT WE FOUND THERE

Helen Delaporte

We were looking for a dead man--one who had been buried over a century ago; and we found a dead man--one who had not been buried at all.

One of the activities of the DAR involves marking the graves of soldiers of the American Revolution. The national organization has rigid standards for this activity, and a local chapter may find that it takes a year or more to complete the required process. First we authenticate the soldier whose grave is to be marked. We find his record, which is usually not very difficult to do; but this calls for research and correspondence that can take several months. Then we must locate the grave as accurately as possible. Down here in southwestern Virginia and east Tennessee, many of the old soldiers were buried without gravestones or in graves that were marked with limestone or sandstone that has crumbled beyond recognition. "National" takes a reasonable attitude toward our problems. But we are all very anxious to be accurate, andidentifying unmarked or untended graves can be very difficult.

When the soldier has been researched and the grave located, a bronze marker is ordered and paid for by the chapter, and a ceremony is held at the grave when the marker is put in place.

The grave we were looking for was that of Adoniram Philipson. Philipson enlisted in 1778 at the age of seventeen and managed to be so severely wounded in his first battle that he was a cripple for life. It was a long life; and since Philipson died in 1851, and thus appeared in the 1850 census as a resident of Ambrose County, Virginia, we had assumed that we would find his grave without much search. He ought to have been with the rest of his family in the cemetery at Ambrose Courthouse.

But he was not. The chapter began work on poor old Adoniram in 1976 as a Bicentennial project. By the time Philipson died, there were few Revolutionary War veterans remaining; and Adoniram enjoyed considerable fame in our corner of the world. Thus there was an abundance of records. But we were absolutely balked when we tried to locate the grave.

We never quite gave the project up, but it was knocking around as unfinished business for almost ten years--until, in fact, I received a letter from George FitzSimmons Francis of Roanoke. Mr. Francis is very knowledgeable about southwest Virginia history; and in his researches he had found correspondence in which there was the sentence: "We laid Uncle Ad beside Cousin Emily Dunbar." The writer was Elizabeth Philipson Davis.

This information gave us a strong lead to follow because the Dunbars were a numerous family along the Holston where it flows into the state of Tennessee.

After some intense research, our Elizabeth Wheeler turnedup evidence that Emily Dunbar was a daughter of Adoniram Philipson's youngest sister. And when Elizabeth reported this to our November meeting last year, Margaret Chalmers, who grew up in the valley, announced that the Dunbars, although they had died out or moved away long before her time, were buried in great numbers in the Brown Spring Cemetery. And wonder of wonders, the Brown Spring Cemetery is just barely above the Tennessee line. Otherwise a Virginia chapter would be unable to mark the grave.

We learned all of that in the November meeting and were so encouraged that I thought we ought to complete this business right away.

With the Christmas music, however, and gifts, and cards--not to mention family--and with perfectly horrible weather in January, I felt that Adoniram's grave could go unmarked at least until we had a few sunny days.

The first such day came on February 22--Washington's real birthday, and a Tuesday. The sun was just rising clear over the knobs--it had not done so for three weeks--as Henry was getting off to the office. It seemed to me that all things were auspicious.

I called Margaret Chalmers, indispensable because she would have to pilot me to the cemetery. Yes, she could go--she would be glad to get out of the house.

Then because Elizabeth Wheeler was not only on the committee, but also because she enjoys cemeteries more than any other person I have ever known, I called her; and she could go.

I have to confess that I hesitated before I called Harriet Bushrow. If I had not called her, we might never have solved the mystery. But that is neither there nor there, because I called her although I had a qualm about taking her to such a place as the Brown Spring Cemetery. She is eighty-six and had a serious bout with flu in January. She is not as steady onher feet as she used to be. She is not actually large--that is to say not remarkably so--but because of the terrain we might encounter and the flu she had just had, I was afraid there might be difficulty.

Then I told myself that undoubtedly Harriet had been shut up in the house for several weeks and it would really be good for her to get out. There is, of course, a certain friction between Harriet and Elizabeth; and I suppose I had better explain why.

In order to join the DAR, one must be able to prove her legitimate descent from someone who fought on the American side in the Revolution or someone who furnished material aid to the colonists. After descent has been proved, she "goes in" on such-and-such as ancestor. The daughter then wears on her blue and white DAR ribbon a gold bar with the ancestor's name and rank engraved on it. If the daughter has other revolutionary ancestors, she may send proof to National and wear additional ancestor bars. Some daughters take great pride in the number of bars decorating their ribbons.

Elizabeth Wheeler has thirty-two bars!

That is, in fact, one gold bar for every male ancestor of military age in her entire lineage at the time of the Revolution. And she has three other ancestors she could claim in cases where both father and son aided the colonists.

I don't know that Elizabeth is unique in this matter, but it is a rare daughter that glitters as she does when she drapes her ribbons over her modest little chest. On the other hand, there is not a single commissioned officer in the whole collection. As Elizabeth herself will say, they were very ordinary people. But she will add that they all did their duty and--what is more important for her purposes--left a record of it.

Harriet, on the other hand! Well, Harriet has only three bars, and it rankles, because Harriet Gardner Bushrow is decidedly aristocratic with glamorous ancestors that far outshineElizabeth's. One was Major General Archibald Hadley, and another was Lieutentant General Nathan Andrews. But Harriet can secure ancestral bars for neither of these. General Andrews, being somewhat older than Hadley, had a beautiful daughter. After the war Hadley was so captivated by Miss Andrews that he eloped with her, leaving behind a legal Mrs. Hadley and several small and very legitimate Hadleys. The Hadley-Andrews alliance prospered without benefit of law, and the descendants married into the best families. Since Harriet's mother was twice a Hadley (that is, there was a marriage of cousins a few generations ago), the two generals appear twice in her ancestry and thus eliminate four possible bars.

Physically too, Harriet and Elizabeth are as different as can be. Elizabeth is somewhat under five feet tall and weighs in the neighborhood of ninety in her galoshes. At seventy-five, she is a lively, bright-eyed retired domestic science teacher, who always wears a little dark suit and a white shirt waist with ruffled collar and cuffs.

Harriet, on the other hand, seems to have inherited the military bearing of her famous and illegitimate ancestors. Even now she can draw herself up and be the handsomest figure in the room.

Although Harriet's house is neither large nor old--and I might add that it is very plain--she has furnished it with moveables of museum quality--not at all the usual personal collection, for she had nothing made after 1830 or originating at a distance greater than one hundred miles of the Virginia-Tennessee border.

Harriet wears pronounced colors--a good strong rose, forest green, or russet--and hats with wide brims, always sloping at a raffish angle so that she looks like a duchess by Leley or even Van Dyck. And there is always her cut crystal necklace of which she is so fond.

Enough about Harriet. Now let me say something about Margaret Chalmers.

Of course, there's really not much to say about Margaret. Her husband sold life insurance and apparently bought his own policies, because he died about twenty years ago and left Margaret in comfortable condition. She has no children, but she makes up for that deficiency with nieces, nephews, old aunts and uncles, and endless cousins. I am very fond of Margaret. If possible, I like to have her share a room with me at State Conference.

By the time I had collected everybody in the Pontiac and got on the Valley Pike, it was two-thirty. Since we were going into Margaret's special part of the county, she had her local history well in hand and was eager to entertain us with it.

"Helen," she began in her soft voice, "did you know that Dr. Edmond Spooner camped at Brown Spring in seventeen fifty-eight?"

Seventeen fifty-eight marks the first authenticated exploration of our area.

I: "Did he?"

Elizabeth: "He did." This came with great authority, for that is the sort of thing that Elizabeth knows.

Margaret: "Grandfather Weathered's big log house burned, but the chimneys are still standing. You can see them over there on the left."

Elizabeth: "My ancestor, George Bennington, was a mason; he made half the chimneys in Chinahook County, Father used to say."

I: "How interesting!"

Thus my conversation alternated with the two, each of the ladies contributing scraps of information known only to themselves and leaving Harriet as completely out of it as if shehad stayed at home. Harriet, you see, grew up in South Carolina and has no family ties to our local area.

Harriet's silence was icy. When I glimpsed her in the rearview mirror, that big hat was drooping over her face so that all I could see was the firm set of her jaw and her cut crystal beads flashing as she breathed.

We got behind a school bus just coming out from the Valley Pike Elementary School. As the bus stopped at every farm house, Margaret would recognize at least one child in each group that left the vehicle. This led to an individual detail of family history each time we came to a halt; and since Valley Pike is excessively crooked and also narrow, I had no chance to pass.

Elizabeth, on the other hand, found a way to enlarge the genealogical information related in every story contributed by Margaret. From time to time Harriet made an effort to start a different conversation.

Harriet: "Helen, do you like the Plymouth?"

I: "This is a Pontiac, Harriet."

Harriet: "Oh!"

After another five minutes of Margaret's local history enlarged by Elizabeth's footnotes, Harriet would try again.

Harriet: "Helen, do you find your heating bills high this year?"

We followed Valley Pike to Hipple's Store, then turned on Farm Road 17 until we reached the Hersey place, a grand old log house with clapboard siding and additions in all directions. The oaks are even older than the house and spread above it with great gnarled branches. At Margaret's direction I turned off onto a dirt road, which served well until we passed the Billy Pennybacker place, where the ruts became downright unpleasant and I began to worry about my shock absorbers. I drove on, dead slowly, for about ten minutes--back into the knobs. Margaret pointed out where the BrownSpring Church had stood before it was torn down, and we could see Brown Branch meandering off through the fields. At last we came to a rusty fence and a huge arch made of pipe with a somewhat battered sign hanging from its apex to tell us that we had arrived at the Brown Spring Cemetery. It was rather a pretty cemetery, cut out of the woods and lying between two knobs to the right and to the left. It was somewhat larger than I had expected it would be. Immediately in front of us there was a grassy slope crowned with monuments and stones--leaning this way and that, but always expectantly facing east. Perhaps thirty yards beyond the gate there was a slight rise, and apparently the cemetery sloped around on the other side and continued a short distance up the hollow.

The cemetery association had done an efficient job on the weeds and brambles, and I was relieved to see that I need not have feared that my ladies could not negotiate the terrain.

I am always impressed by the quiet of a country cemetery, and apparently so were my passengers; for as the Pontiac's engine died, our conversation died also.

We disembarked and entered almost timidly--perhaps with the feeling that we were intruding. Quietly we made our way through the gate, the only sound beside our footsteps resulting from Harriet's opening her purse to get a cough drop.

Suddenly Elizabeth broke our reverie with a polite shriek--"Hunsuckers!"

It sounded as though we were being warned of something--possibly a bird that would swoop down and attack us.

"And there's another one!"

Elizabeth is in her personal element in a cemetery, and we could tell that she was prepared to be delighted by this one.

"I have Hunsuckers!"

"Elizabeth Wheeler," Harriet said with annoyance, "What on earth are you talking about?"

"Great-Uncle John Payne married a Hunsucker," Elizabeth explained. "And just look at them!"

"Yes, there were a lot of them," said Margaret.

"Well," Harriet said, slightly out of humor, "by all means let Elizabeth collect her Hunsuckers while the rest of us locate Adoniram Philipson."

We did in fact find Adoniram Philipson. He was among the trees just outside the fence, which was perhaps put up at some time after Adoniram went to his long home. The stone was broken, lying face down and almost buried. It had apparently been in that condition for many years. But since it was only a fragment and the whole stone had not been very large anyhow, I had no trouble prying it up and turning it over. We felt ourselves very fortunate to be able to read:

ADON. PHI

BORN 1760--DI

I took shelf paper and a cobbler's heel from a shopping bag I always carry when I go to a cemetery. A rubbing makes the report a little more interesting to the chapter. I taped the paper to the stone and began rubbing briskly as Harriet and Margaret watched.

Suddenly we heard a stage whisper from Elizabeth and saw her running toward us at a strange little tiptoe pace.

"There is a man up there," she said in an excited whisper. "I think he needs help."

"Well, Elizabeth," Harriet boomed, "did you offer to help him?"

"I did clear my throat," Elizabeth said, "but he didn't move. He's lying partly behind a tombstone. I didn't get too close."

Harriet, always the descendant of generals, led off firmly as I put my rubbing equipment into my market bag. Elizabethand Margaret followed Harriet, and I brought up the rear--somewhat like the barnyard friends of Chicken Little.

At the peak of the slight rise, Elizabeth pointed to a tombstone with MOTHER carved across it in huge letters. Visible from behind one side of it, a pair of legs in blue jeans sprawled at an unnatural angle. A Jack Daniel's bottle lay about a yard away.

When I arrived on the scene, so to speak, Harriet was breathing heavily from her exertion, but she had drawn herself up to her full height, while the other two ladies somehow seemed smaller than themselves. They were a little to the rear of Harriet and gave the impression of frightened children peeking around their mother's skirts.

"I suppose he's drunk," Margaret said.

"Why, he is plainly dead!" Harriet announced as though only a fool would suppose otherwise.

"But perhaps he isn't. Do you suppose we should see if there is a pulse?" Margaret murmured so gently and timidly that I didn't hesitate to go through the motions I vaguely remembered from a long-forgotten course in first aid, saying "hello" loudly and feeling for a pulse.

Of course Harriet was right. The poor man had been attacked savagely about the neck, the lower face, and the left temple with something heavy enough to be frightfully lethal. The eyes were open, and at this point of my examination I discovered something quite surprising. Those eyes did not match. One was brown, very dark, staring at me in the manner of a dead fish. The pupil of the other eye was strange--not clear--as though there were a film across it.

There on my knees, holding that clammy hand, I was aware of two things: first that there was absolutely no pulse; and second that his hand was quite limp, which I realized later meant that rigor mortis had passed.

Even at that time I assumed that the man had been dead for a good while.

I never supposed I would have such an experience, and I certainly would never have been able to guess what my reaction would be. What happened was that the names of my favorite detective fiction authors passed through my mind: Agatha Christie, Marjorie Allingham, Dorothy Sayers. What would Inspector Appleby do in this case? How strange my reaction seems! After all, I am essentially a housewife and a church organist.

Although I wouldn't say that my memory is photographic, nevertheless it is visual. I can look closely at anything, and if I concentrate while I am looking at it, I can recall visually whatever I have observed in that way. I do this when I memorize music. And I was fixing in my visual memory what I was seeing at that time. I noted the peculiarities of the head, the eyes, the ears, the contusions, the clothing--which I immediately saw could not have been intended for this man--and the hands.

Hands tell so much about a person. Although dressed in filthy ragged clothing much too large for him, this man had clean hands. His nails were immaculate, rounded sensibly--and lacquered with clear nail polish. I was so surprised by this detail that I turned the hands over and examined the palms and the tips of the fingers--strong fingers; and there was a callus at each fingertip.

"We must call the sheriff," I said. Though only slightly north of the Tennessee line, we were of course in Virginia, (an obvious necessity if the grave is to be marked by a Virginia chapter); and so it was the sheriff on the Virginia side that must be notified.

"We can phone from Billy Pennybacker's place," Margaret volunteered, her voice not loud but alive with shock and excitement. Surely the Old Orchard Fort Chapter had neverbeen involved in anything like this. We made our way back to the Pontiac and crawled down that rutted lane, about three quarters of a mile.

Rachel Pennybacker is a handsome woman of about sixtyfive. Long a friend of Margaret, she opened her house to the four of us with immediate hospitality and great interest in our sensational discovery. We trooped through to her old-fashioned kitchen, where the phone was, and took possession.

The deputy who answered my call told us to stay where we were until the sheriff could get there.

Mrs. Pennybacker put a pot of coffee on the stove, and we discussed first the unknown dead man in the cemetery, then Adoniram Philipson, African violets, Sears appliances, and finally the Pennybacker grandchildren. At that point Harriet announced that she would visit the lavatory. Mrs. Pennybacker offered to take her upstairs to show her where the bathroom was, but Harriet firmly insisted that she could find it herself. Margaret gave me a knowing look, because we all know that if Harriet says she wants to use the bathroom, it usually means that she is going to explore the house.

Ten minutes later Harriet returned to us and said to our hostess, "I couldn't help noticing your cannonball bed. I suppose it was in your family?"

It was, and the conversation readily turned into a lecture on candle stands, clothespresses, mule-eared chairs, and bandboxes.

Finally, when Sheriff Gilroy arrived with Deputy Lassiter, Margaret, Elizabeth, and I left Harriet at the Pennybacker place because of her recent recovery from flu and returned to the cemetery.

The sheriff's car preceded mine; and when we got to the cemetery fence, the sheriffs radio was squawking away to let us know that a TV crew was on its way. This would be a treat for Channel Five. Our station has a hard time filling up itslocal news program and is always delighted with any gruesome event to fling at the public.

A good many things began to happen, and it was a long, drawn-out process. I was glad that Henry had an evening meeting of the library board and would not be home for dinner.

When I finally got to the house, I felt as if I had been gone a week. I took a hot bath, threw on a robe, made myself a tuna sandwich, and tried to work on the music for Holy Week, but it was hard to put the events of the day out of my mind.

At a quarter to ten I turned on the TV to Channel Five for the local news. I sat there through Ed Asher's Chevrolet ad, the efforts of the Boys Club to raise money for weight-lifting equipment, the little old lady on the Virginia side who had won $20,000 in the lottery, and then--the only grisly event of the day--our discovery at Brown Spring Cemetery.

They gave us almost eight minutes with shots of the cemetery, shots of the body covered with a black cloth, and a glimpse of me in the background. There was a good shot of Margaret, quite a lot of Sheriff Butch Gilroy blustering around, and finally a very good interview with Elizabeth.

I wish National could have seen that interview, because Elizabeth handled it beautifully. She explained fully and clearly what the DAR is and does. She included our support of schools, particularly the ones we own, like our Kate Duncan Smith DAR School in Alabama. And she spoke of the scholarships we give in American history, government, nursing, and occupational therapy. And of course she explained about locating and marking the graves of Revolutionary soldiers and patriots. There was a shot of the fragment of Philipson's headstone, and Elizabeth was in her glory explaining who he was in the most minute detail; and yet she did it all charmingly.

Since Elizabeth has been one of our best publicity chairmen for many years in the past, she knew exactly what to do, giving the name of our chapter--Old Orchard Fort--several times and linking the afternoon's events to the legitimate activities of the NSDAR.

I was still grinning like the cat who had been in the cream when Henry came home a few minutes later.

He had had a long and troublesome meeting at the library and was tired, but he revived considerably when I began to tell him what had happened in my life since he had last seen me.

I began at the very beginning and went through every detail. The telecast and my visual memory brought it back to me with absolute clarity.

"Henry," I said when I had finished my story, "that poor man had the most beautiful hands!"

"Beautiful hands!" Henry exclaimed. "Are you talking about the dead? The dead man!"

"Yes, he must have been an extraordinary person."

"De mortuis nil nisi bonum," Henry said. "You found him charming, I dare say." He treats me this way sometimes.

"Charming," I echoed. There is no point in resisting Henry's sarcasm. 'Perhaps he was not as conversational as he might have been," I added.

It was the discordance of the thing--the hands so carefully groomed. Nothing would lead one to expect such hands. Not the clothing, which was three or four sizes too big--not the discarded Jack Daniel's bottle. Nor did the manner of death go with the hands. I told Henry what I was thinking.

"Let the sheriff worry about that," he said.

I followed Henry to bed. In the morning the Banner-Democrat had a story on the front page as follows:

CITY WOMEN FIND CORPSE IN CEMETERY

Members of a local women's organization were surprised to find the body of an unknown man apparently killed in a drunken brawl. "I never was so surprised in my life," said Ms. Elizabeth Wheeler, who discovered the body. "There he was lying behind a tombstone."

Sheriff Calvin ("Butch") Gilroy reported that no identification was found on the body and assumes that the deceased was a transient. "Two or three of them probably got drunk and started a fight," Gilroy speculated. "We get lots of this."

The attack upon the deceased was directed at the face and throat apparently with a blunt object. County Coroner Donald R. Woolwine reported that the death was caused by rupture of the thorax.

I said to Henry, who was reading the editorial page, "Butch Gilroy is going to attribute everything to a fight between drunks and forget about it."

"Oh yes, that business out at Brown Spring," Henry said. "It wouldn't surprise me at all."

"Well," I said, thinking it over. "I was on the ground; I know as much about it as Butch Gilroy; and I say he is wrong. And I don't like his cavalier attitude. He obviously expects to dismiss the whole thing as if it didn't matter." Gilroy belongs to a fraternal order or two. When the B.O.P. brings the circus here, he dresses up like a clown, gets on the tube, and begs us all to buy tickets so that underprivileged children can see the show. He boosts the high-school teams--which is all very well; but he does as little work in the sheriff's office as possible unless he can appear on television. When election time comesaround, he is to be seen with a toothy grin all over town. I do not like him.

Henry had now turned to the market reports. I could tell by the way he was holding the paper that he had got down to Pennsylvania Power and Light. Henry is a darling man, but he tends to overlook me at times, and I sometimes don't appreciate that.

"Henry!"

"Yes?"

"Well, it was a murder, you know; and it has to be taken as seriously as it would be taken if the victim had been the president of the Planters Trust Bank"

"Oh, yes," he said, lowering his paper. "In theory crimes should never go unpunished. But you know, my dear, there are crimes that cannot be explained and therefore cannot be punished. And a casual crime such as this one appears to be is the most hopeless situation that law enforcement can face: an unknown--in an out-of-the-way place that has no logical connection with the murdered individual or with the crime--is killed in a fight with another unknown, who has never been on the scene before and will never be on the scene again. No witnesses. No suspects. No motive. What can you expect of a sheriff like Gilroy--a good old boy who is dumb enough to like being sheriff and smart enough to hang on to the job. He hasn't got enough money in his budget to hire a staff capable of handling the routine cases that come his way. Even if he put half his force on a hopeless case like this, he would have to draw men from other duty where they are actually serving the county and send them on this goose chase. There is no possible satisfactory conclusion for a case like this, and he probably feels that there are better ways to spend his time and the taxpayers' money."

"You, Henry Delaporte," I said, "have told me times without number about the responsibility of the law to extendequal protection to every citizen, no matter who he is or how unable he is to pay a lawyer. You even addressed the chapter during Constitution Week on this very topic. How can you sit there and condone a system that protects the rights of a man who's known in the community and ignores a stranger?"

"I know, but the casual murder of a bum is not at all likely to be solved."

I thought that one over a second while Henry returned to his paper.

"He was not a bum," I said.

"He had beautiful hands," Henry mumbled, his head still in the paper.

"And he was murdered casually by hoodlums--in the Brown Spring Cemetery?" I continued. Look--he must have been murdered somewhere else. There is no other possibility." I could not get the inconsistencies out of my mind. Those misfit clothes ... They couldn't have been his.

Inhaling the fumes from my coffee, I reexamined that picture I had summoned to my mind. I could see the face that had been so severely battered--such gashes on that face--and yet it now occurred to me that there was no blood on the shirt. It came to me, as things do, like a picture. And then I noticed something that I had not noticed before.

"Henry, there's something else."

"All right, what?" Henry reached across the table and took the section of the paper that had been lying in front of me.

"He had quite a tan."

"Don't most bums have a tan?"

"He was clean-shaven and had a tan--like a tan a man might get on a golf course."

"Oh, come on! Your imagination is out of control, my dear."

"The tan went right on up to his bald head, which wasn't tanned at all."

"The man wore a hat."

"Yes, I suppose so." And yet there was a distinct line where the hair should have begun, but perhaps Henry was right. Perhaps I was playing my game too hard. I concentrated on my coffee.

A cup of good coffee usually puts dreamy things into my head. So I tried to think of something more pleasant. What the poor murdered man might perhaps have looked like before he was so savagely battered. I visualized him in evening clothes. As I saw him, he was rather handsome. I made him out to be about fifty. There he was--but with that bald head! Then something in my brain clicked. The sensitive hands, the white tie and tails, and perhaps a toupee--bowing after a performance of some kind. Then I thought about the calluses on his fingers. There was a clue there. Certain musicians, such as guitarists, have such calluses. Whatever might be the truth, I was convincing myself more and more of my original statement. "He was not a bum," I insisted.

Henry laughed. "All right, my dear, your man was a very important fellow, but you'll have a hard time convincing the sheriff of that."

That was Wednesday. Wednesday means choir practice, and I had laund

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...