- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

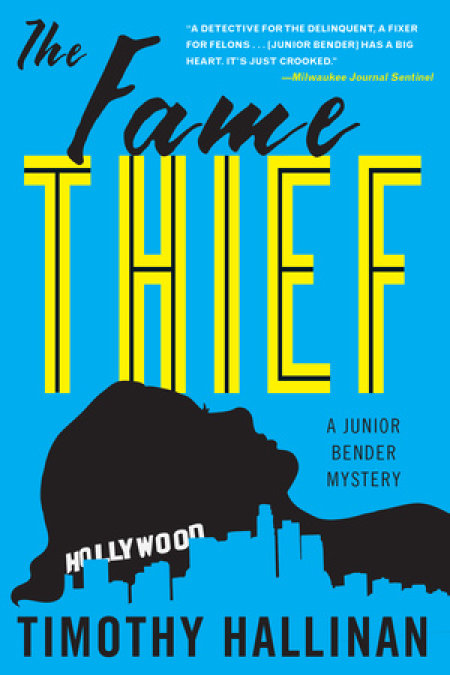

The highly anticipated, laugh-out-loud third installment in the fan-favorite Junior Bender mysteries

There are not many people brave enough to say no to Irwin Dressler, Hollywood’s scariest mob boss turned movie king. Even though Dressler is ninety-three years old, LA burglar Junior Bender is quaking in his boots when Dressler’s henchmen haul him in for a meeting. Dressler wants Junior to solve a crime he believes was committed more than seventy years ago, when an old friend of his, once-famous starlet Dolores La Marr, had her career destroyed after compromising photos were taken of her at a Las Vegas party. Dressler wants justice for Dolores and the shining career she never had.

Junior can’t help but think the whole thing is a little crazy. After all, it’s been seventy years. Even if someone did set Dolores up for a fall from grace, they’re probably long dead now. But he can’t say no to Irwin Dressler—no one can, really—so he starts digging. What he finds is that some vendettas never die; they only get more dangerous.

Release date: July 2, 2013

Publisher: Soho Crime

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Fame Thief

Timothy Hallinan

My business plan calls for long periods of inactivity

Irwin Dressler crossed one eye-agonizing plaid leg over the other, leaned back on a white leather couch half the width of the Queen Mary, and said, “Junior, I’m disappointed in you.”

If Dressler had said that to me the first time I’d been hauled up to his Bel Air estate for a command appearance, I’d have dropped to my knees and begged for a painless death. He was, after all, the Dark Lord in the flesh. But now I’d survived him once, so I said, “Well, Mr. Dressler—“

A row of yellow teeth, bared in what was supposed to be a smile but looked like the last thing many small animals see. “Call me Irwin.”

“Well, Mr. Dressler, at the risk of being rowed into the center of the Hollywood Reservoir wired to half a dozen cinder blocks and being offered the chance to swim home, what have I done to disappoint you?”

“Nothing. That’s the problem.” Despite the golf slacks and the polo shirt, Dressler was old without being grandfatherly, old without going all dumpling, old without getting quaint. He’d been a dangerous young man in 1943, when he assumed control of mob activity in Los Angeles, and he’d gone on being dangerous until he was a dangerous old man. Forty minutes ago, I’d been snatched off a Hollywood sidewalk by two walking biceps and thrown into the back seat of a big old Lincoln Town Car, and when I’d said, “Where’s your weapon?” the guy in the front said, “Irwin Dressler,” and I’d shut up.

Dressler gave me a glance I could have searched for hours without finding any friendliness in it. “You got yourself a franchise, Junior, a monopoly, and you’re not working it.”

I said, “My business plan calls for long periods of inactivity.”

“That’s not how this country was built, Junior.” Like many great crooks, even the very few at his stratospheric level, Dressler was a political conservative. “What made America great? I’ll tell you: backbone, elbow grease, noses to the grindstone.”

“Sounds uncomfortable.”

Dressler had lowered his head while he was speaking, perhaps to demonstrate the approved nose-to-the-grindstone position. Only his eyes moved. Beneath heavy white eyebrows, they came up to meet mine, as smooth, dry, and friendly as a couple of river stones. He kept them on me until the back of my neck began to prickle and I shifted in my chair.

“This is amusing?” he said. “I’m amusing you?”

“No, sir.” I picked up the platter of bread and brie and said, “Cheese?”

“In my own house he’s offering me cheese.” Dressler addressed this line to some household spirit hovering invisibly over the table. “It’s true, it’s true. I’ve grown old.”

“No, sir,” I said again. “It’s, uh, it’s . . .”

“The loss of American verbal skills,” he said, nodding, “is a terrible thing. Even in someone like you. I remember a time, this will be hard for you to believe, when almost everyone could speak in complete sentences. In English, no less. What have I done, Junior, that you should laugh at me? Get so old that I don’t frighten you any more?”

“I wasn’t—”

“I bring you here, I give you cheese, good cheese—is the cheese good, Junior?”

“Fabulous,” I said, seriously rattled. This had the earmarks of one of Irwin’s legendary rants, rants that frequently ended with one less person alive in the room.

“Fabulous, he says, it’s fabulous. What are you, a hat maker? Of course, it’s fabulous. The Jews, you know, we’re a desert people. The two gods everybody’s killing each other over now, Jehovah and the other one, Allah, they’re both desert gods, did you know that, Junior?”

“Um, yes, sir.”

“Desert gods are short on forgiveness, you know? And we Jews, we’re the chosen people of a desert god and hospitality is part of our tradition, and now I’m going to get badmouthed for my cheese by some pisher, some vonce—you know what a vonce is, Junior?”

“No, sir.”

“It’s a bedbug, in Yiddish, great language for invective. I’ll tell you, Junior, I could flay the skin off you using Yiddish alone, I wouldn’t even need Babe and Tuffy in the next room there, listening to everything we’re saying so they can come in and kill you if I get too excited. My heart, you know? A man my age, I can’t be too careful. Someone gets me upset, better for Babe and Tuffy just to kill them first, before my heart attacks me.”

“I’m sorry, Mr. Dressler. I wasn’t thinking.”

“But thinking, Junior, that’s what you’re supposed to be good at.” He reached out and took some bread off the platter, which I was apparently still holding, and said, “Down, put it down. Did I offer you wine?”

“Yes, sir.” He hadn’t, but I wasn’t about to bring it up. I put the tray in front of him on the table. Inched it toward him so he wouldn’t have to lean forward.

“I still got arms,” he said, tearing some bread. “What were we talking about before you got so upset?”

“My franchise.”

“Right, right. You may not know this, Junior, but you’re the only one there is. You’re like Lew Winterman when he—did you know Lew?”

“Not personally.” Lew Winterman had been the head of Universe Pictures and long considered the most powerful man in Hollywood, at least by those who didn’t know that the first thing he did every morning and the last thing he did every night was to phone Irwin Dressler.

“When he and I thought of packaging, we had to get horses to carry it to the bank, that’s how much the money weighed,” Dressler said. “You know packaging? You can have Jimmy Stewart for your movie, but you also gotta take some whozis, I don’t know, John Gavin. And every other actor in your picture and also the cameraman and the writers, and he represented them all, Lew did. For about a year after we figured it out, he was the only guy in Hollywood who knew how to do it, and he did it ten hours a day, seven days a week. You know how much he made?”

“No, sir. How much?”

“Don’t ask. You can’t think that high. So you’re like that now, like Lew, but on your own level, and what are you doing? Sitting around on your tuchis, that’s what you’re doing. That whole thing you got going? Solving crimes for crooks? And living through it? You got Vinnie DiGaudio out of the picture for me with every cop in L.A. trying to pin him. You helped Trey Annunziato with her dirty movie, although she didn’t like it much, the way you did it. When four hundred and eighty flatscreens got bagged out of Arnie Muffins’ garage in Panorama City, you brought them back, and without a crowd of people getting killed, which is something, the way Arnie is. You’re it, Junior, you’re the only one. And you’re not working it.”

“Every time I do it,” I said, “I almost get killed.”

“Ehhh,” Dressler said. “You’re a young man, in the prime of life. What’re you, thirty-eight?”

“Thirty-seven.”

“Prime of life. Got your reflexes, got all your IQ, at least as much as you were born with. You’re piddling along with a franchise that, I’m telling you, could be worth millions. Where’s the wine?”

I said, “I’ll get it.”

“You’ll get it? You think I’m going to let you in my cellar?”

He picked up a silver bell and rang it. A moment later, one of the bruisers who’d abducted me and dragged me up here came into the room. He was roughly nine feet tall and his belt had to be five feet long, and none of it was fat.

“Yes, Mr. Dressler?”

“Tuffy,” Dressler said. “You I don’t want. Where’s Juana?”

“She’s got a headache.” Despite being the size of a genie in The Thousand and One Nights, Tuffy had the high, hoarse voice of someone who gargled thumbtacks.

“So mix her my special cocktail, half a glass of water, half a teaspoon each of bicarbonate of soda and cream of Tartar. Stir it up real good, till it foams, and take it to her with two aspirins. And get us a bottle of—what do you think, Junior? Burgundy

or Bordeaux?”

“Ummm—”

“You’re right, it’s not a Bordeaux day. Too drizzly. We need something with some sunshine in it. Tuffy. Get us a nice Hermitage, the 1990. Wide-mouthed goblets so it can breathe fast. Got it?”

Tuffy said, “Yes, Mr. Dressler.”

I said, “And put on an apron.”

Tuffy took an involuntary step toward me, but Dressler raised one parchment-yellow hand and said, “He just needs to pick on somebody. Don’t take it personal.”

Tuffy gave me a little bonus eye-action for a moment but then ducked his head in Dressler’s direction and exited stage left.

Dressler said, “So. People try to kill you.”

“Occupational hazard. I’m working for crooks, but I’m also catching crooks. If I solve the crime, the perp wants to kill me. If I don’t solve it, my client wants to kill me.”

“Nobody’s really tough any more,” Dressler said, shaking his head at the Decline of the West. “You know how we took care of the Italians?”

I did. “Not really.”

“Kind of a long way to say no, isn’t it? Three syllables instead of one. So, okay, the Italians came out to California first, and when we got here from Chicago it was like Naples, just Guidos everywhere, running all the obvious stuff: girls, betting, alcohol, unions, pawnshops, dope. Well, we were nice Jewish boys who didn’t want to make widows and orphans everywhere so you know what we used? Never mind answering, we used baseball bats. Didn’t kill anybody except a few who were extra-stubborn, but we wrapped things up pretty quick. See, that’s tough, walking into a room full of guns with a baseball bat. Ask a guy to do that these days, he’d have to be wearing Depends.”

I said, “Huh.”

Dressler nodded a couple of times, in total agreement with himself. “But let’s say the people who want to kill you, give them the benefit of the doubt, let’s say they could manage it. And all that nonsense with a different motel every month isn’t really going to cut it, is it? What’s the motel this month? Valentine something?”

“Valentine Shmalentine,” I said, feeling like I was drowning.

“In Canoga Park.”

“Valentine Shmalentine? Kind of name is that?”

“Supposed to be the world’s only kosher love motel.”

“What’s kosher mean for a love motel? No missionary position?”

“Heh heh heh,” I said. He wasn’t supposed to know about the motel of the month. Nobody was, beyond my immediate circle: my girlfriend, Ronnie; my daughter, Rina; and a couple of close friends and accomplices, such as Louie the Lost. But, I comforted myself, even if word about the motels had leaked, I still had the ultra-secret apartment in Koreatown. Nobody in the world knew about that except for Winnie Park, the Korean con woman who had sublet it to me, and Winnie was in jail in Singapore and had been for seven years.

“So the motels don’t work,” Dressler said, “not even taking the room next door like you do, with the connecting door and all, to give you a backup exit. It’s a cute trick though, I’ll give you that. So I’ll tell you what you need. Since you can’t hide, I mean. You need a patron, so people know you’re under his protection. Somebody who wouldn’t kill you even if they caught you playing kneesie with their teenage daughter, and you know how crooks are about their daughters.”

“What I need,” I said, “is to quit. Just do the occasional burglary, like a regular crook.”

“Not an option,” Dressler said. “You agree that everyone, even a schmuck like Bernie Madoff, has the right to a good defense attorney?”

I examined the question and saw the booby trap, but what could I do? “I suppose.”

“Then why don’t they deserve a detective when some ganef steals something from them? Or tries to frame them, like Vinnie Di Gaudio? You remember helping Vinnie Di Gaudio?”

“Sure. That was how I met you.”

“See? You lived through it. You got told to keep Vinnie out of the cops’ eyes for a murder even though it looked like he did it, and you kept me out of the picture so my little line to Vinnie shouldn’t attract attention. This was a job that required tact and finesse, and you showed me both of those things, didn’t you? And now you’re eating this nice cheese and you’re about to drink a wine, a wine that’ll put a choir in your ear. So quitting is not an option.”

“What is an option?” I held up the platter, feeling like I was making an Old-Testament sacrifice. “Cheese? It’s terrific cheese.”

“You can lighten up on the cheese. I know it’s good. You thought this dodge up all by yourself, Junior, and I respect that. Something new. Gives me hope for your generation. Like I said, a patron, patronage, that’s what you need. And an A-list client, somebody nobody’s going to mess with.”

“A client and a patron,” I said. “Two different people?”

“That’s funny,” Dressler said gravely. “You gotta work with me here, Junior. I’ve got your best interests in mind.”

“And don’t think I don’t appreciate it. But I—”

“I do think you don’t appreciate it,” Dressler said, “and I don’t give a shit.”

I said, “Right.”’

“And also, I gotta tell you, this is a job I wouldn’t give to just anybody. The client, for example—”

“I thought you were the client.”

“Literal, you’re too literal. I’m the client in the sense that I’m the one who chose you for the job and the one who’ll foot the bill. But think about it, Junior. Am I somebody some crook’s going to hit?”

“No.”

“How stupid would anybody have to be to hit me?”

“Someone would have to be insane to take your newspaper off your lawn.”

“Not bad. Sometimes I get glimpses of something that makes me think maybe you’re smart after all. No, the client, in the sense that she’s the one who got ripped off, the client is—are you ready, Junior?” He sat back as though to measure my reaction better.

I put both hands on the arms of my chair to demonstrate readiness. “Ready.”

“Your client is . . . Dolores La Marr.”

There was a little ta-daaa in his voice and something expectant in his expression, something that tipped me off that this was a test I didn’t want to fail. So I said, “You’re kidding.”

“Dolores,” he said, nodding three times, “La Marr.”

I said, “Wow. Dolores La Marr.”

“The most beautiful woman in the world,” Dressler said, and there was a hush of reverence in his voice. “Life magazine said so. On the cover, no less.”

Life ceased publication on a regular basis in 1972, which I know because I once stole a framed display of the first issue, from 1883, paired with the last, both in mint condition. I got $6500 for it from the Valley’s top fence, Tetweiler, and Stinky turned it around to a dealer for $14 K. A year later it fetched $22,700 at auction while I gnashed my teeth in frustration. So it seemed safe to ask Dressler, “What year was that?”

“Nineteen-fifty. April 10, 1950. She was twenty-one then. Most beautiful thing I ever saw in my life.”

The penny dropped. Dolores La Marr. Always referred to as “Hollywood starlet Dolores La Marr” in the sensational coverage of the Senate subcommittee hearings into organized crime at which she testified, reluctantly, during the early 1950s.

I said, “She’d be what now, eighty?”

“She’s eighty-three,” Dressler said. “But she admits to sixty-six.”

“Sixty-six?” I said. “That would mean Life named her the most beautiful woman in the world when she was four. I know journalism was better back then, but—”

“A lady has her privileges,” Dressler said, a bit stiffly. “She’s as old as she wants to be.”

“Well, sure.”

“I gotta admit,” Dressler said, “I didn’t expect you to know who she was. “What’re you, thirty-eight?”

“Thirty-seven,” I said again.

“Oh, yeah, I already asked that. Don’t think it’s cause I’m getting old. It’s cause I don’t care. But you know, you’re practically a larva, but you remember Dolly.”

“Dolly? Oh, sorry, Dolores. I remember her because I’m a criminal. I read a lot about crime. I pay special attention to that, just like some baseball players can tell you the batting averages of every MVP for fifty years. I read the old coverage of the Congressional hearings into organized crime like it was a best-seller.”

Tuffy came in with an open bottle of wine and a couple of glasses on a tray. To me, he said, “Say one cute thing, and you’ll be drinking this through the cork.”

I asked Dressler, “You let the help talk to your guests like that?”

“Tuffy, be nice. If Mr. Bender and I don’t reach a satisfactory conclusion to our chat, you have my permission to put him in a full-body cast.” Dressler looked at me. “A little joke.”

I waited while Tuffy yanked the cork and poured. Then I waited until he’d left the room. Then I waited until Dressler picked up his glass and said, “Cheers.” Only then did I pick up my own glass and drink. An entire world opened before me: fine dust on grape leaves in the hot French sun, echoing stone passageways in fifteenth-century chateaus, the rippling laughter of Emile Zola’s courtesans.

“Jesus,” I said. “Where do you get this stuff?”

“Doesn’t matter,” Dressler said. “They wouldn’t deal with you. Tell you what. You take care of Dolores and I’ll see you get a case of this.”

“And a case of the one we had last time,” I said. “I’ve thought about it every day since I drank it.”

“You drive a hard bargain. Done. If you can fix things for Dolores. If not, I’ll let Tuffy pay you.”

“I don’t need threats,” I said, feeling obscurely hurt. “If I say I’ll do something, I’ll do it. And I’ll do it the best I can.”

“That’s fine,” Dressler said. “But I might need better than that."

2

And Makes Me Poor Indeed

“So,” I said, halfway into the second glass, “what did somebody do to Dolores La Marr?”

“What’s the most valuable thing we’ve got, Junior?”

“We?” I asked. “Or me?”

“Let’s start with you.” Dressler rang the bell again.

“My daughter,” I said. “Rina.”

“Okay, that’s you. That’s good, family should always come first, but think bigger. Look, there’s one thing you’ve got that someone can steal, you listening? Of course, you’re listening. And once they steal it, they’re no richer, but you’re a lot poorer. You know what it is?” Tuffy came into the room. “Be a nice guy,” Dressler said to him, “and get us some green olives. The big ones with that weird red thing in it.”

“Pimento,” I said.

Dressler said, “Did I ask you?”

“Sorry.”

“In the refrigerator. In the door, second shelf down, on the right. Jar with a green label. Don’t bring us the jar, just put three olives each on six of the big toothpicks, in the second drawer to the left of the sink, put them on the good china with some napkins, and bring them in. That’s eighteen olives on six toothpicks. And don’t touch them with your fingers.”

Tuffy’s forehead wrinkled in perplexity, and I thought he probably did that a lot. “How do I get them on the toothpick without touching them?”

Dressler said, “You want I should come in and do it myself?”

Tuffy took a step backward. “No, no, Mr. Dressler.”

“Good. You figure it out. Every time I have to do something myself, I figure that’s one less person I need.”

As Tuffy scurried from the room, and I said, “I admire your management style.”

“We’ll see how much you admire it when it’s aimed at you. Answer my question. What do you have that somebody can steal and it hurts you but doesn’t give them bupkes?”

“Oh,” I said. Rephrased, there was something familiar about it. “I’ve got a kind of tingle.”

“So tell your neurologist. Do you read Shakespeare?”

“Yes.”

He looked at me, one eye a lot smaller than the other. “And? What is it?”

“My good name,” I said. The window to my memory opened noiselessly, and in my imagination I dropped gratefully to my knees in front of it. I closed my eyes, and said,

“Good name in man and woman, dear my lord,

Is the immediate jewel of their souls.

Who steals my purse steals trash; ‘tis something, nothing;

‘Twas mine, ‘tis his, and da-da, da-da,-da-da—”

“Has been slave to thousands,” Dressler prompted, and I finished it up:

“But he that filches from me my good name

Robs me of that which not enriches him,

And makes me poor indeed.

“Iago,” I said. “Not someone who deserves a good rep.”

“If he hadn’t had one,” Dressler said, “he’d have been hung before the end of Act One. Play should have been called Iago, not Othello. Why name a play after the mark?” He drank the wine as if it were Kool-Aid. “Who needs a good reputation better than a crook?”

“Good point.”

“That was a question.”

Context is everything, and we’d been talking about Dolores La Marr. “An actress.”

“I could learn to like you,” Dressler said, “maybe. First the Shakespeare, then the common sense. They shouldn’t call it common sense, you know? Nobody’s got it any more.”

I didn’t think there had ever been a period in human history when common sense had been thick on the ground, but it didn’t seem like an observation that would interest Dressler. So I said something he’d undoubtedly heard a lot of. I said, “You’re right.”

“Everything, the girl lost everything. She was getting good parts in bad movies, working up to bad parts in good movies, and then Lew was going to give her a good part in a good movie. Her whole life, she wanted one thing, just one thing, and she worked like a bugger to get it. And then somebody took it all away from her. He that filches from me my good name,” Dressler declaimed, “Robs me of that which not enriches him—”

“And makes me poor indeed,” I said in unison with him. We both gave it a little extra, since the wine had kicked in, and Tuffy, coming in with a plate in his hands, stopped as though he’d found the two of us sitting shoulder to shoulder at the piano, playing “Chopsticks.”

“I couldn’t do it,” he said, looking worried. “I brought the olives and the toothpicks, but the olives are just rolling around on the dish ‘cause I couldn’t get them on the toothpicks. I ate the ones I touched. I figure the genius here can figure it out.”

“In my sleep,” I said.

“Just put it down,” Dressler said. “Where’s Babe?”

“He’s, uh, he’s taking a nap.”

“What is this? Juana’s got a headache, Babe’s asleep, and you can’t put olives on a toothpick. I’ve gotten old, I’ve gotten old. Nobody’s afraid of me any more.”

“I am,” I said.

“You don’t count. Wake Babe up. He can sleep tonight.”

“Yes, Mr. Dressler.” Tuffy was backing up.

“Aahhh, let him sleep,” Dressler said. “They got a baby at home. Probably up all night.”

“Yes sir.” Tuffy licked his lips and fidgeted.

“Just fucking say it,” Dressler said.

“Kid’s teething,” Tuffy said.

Dressler lifted a hand and let it drop. “Achh, I remember. My sister, two of my nieces and nephews. Misery, it’s misery. Okay, let him sleep.”

Tuffy left the room rather quickly, and Dressler said to me, “Give me an olive.”

“I don’t know how to do it, either,” I said. “How to get them on the toothpicks without touching them.”

He pulled his head back, a snake preparing to strike. &ldq

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...