- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

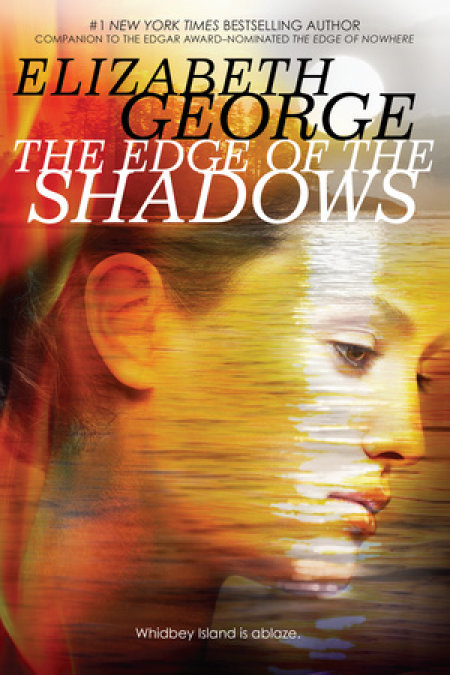

Synopsis

Late summer on Whidbey Island after nine weeks of no rain and fire season has arrived . . . along with a fire starter who soon begins tormenting the residents of this peaceful Pacific Northwest idyll with fires that escalate in intensity. Becca King and her friends Jenn and Derric are with her at the county fair when the third fire starts in a shed housing animals. The shed is destroyed, some of the animals are killed, and Becca hears from the nearby forest the 'whispers' of the fire starter who has remained to watch the havoc. More fires ensue and the situation escalates until someone dies. Becca thinks she knows who's behind it all, but only with the help of her friends and the development of her own incipient psychic talents can the perpetrator be brought to justice.

Release date: May 26, 2015

Publisher: Viking Books for Young Readers

Print pages: 464

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Edge of the Shadows

Elizabeth George

Island County Fairgrounds

The third fire happened at Island County Fairgrounds in August, and it was the first one to get serious attention. The other two weren’t big enough. One was set in a trash container outside the convenience store at a forested place called Bailey’s Corner, which was more or less in the middle of nowhere, so no one thought much about it. Some dumb practical joke with a sparkler after the Fourth of July, right? Then, when the second flamed up along the main highway, right at the edge of a struggling little farmers’ market, pretty much everyone decided that that one took off because an idiot had thrown a lit cigarette from his car window right in the middle of the driest season of the year.

But the third fire was different. Not only because it happened at the fairgrounds, which were just yards away from the middle school and less than a quarter mile from the village of Langley, but also because the flames began during the county fair when hundreds of people were milling around a midway.

A girl called Becca King was among them, along with her boyfriend and her best girl friend: Derric Mathieson and Jenn McDaniels. The three were a study in contrasts, with Becca light-haired, trim from months of bicycle riding, and wearing heavy-rimmed glasses and enough makeup to suggest she was auditioning for membership in the reincarnation of the rock band Kiss; Derric tall, well-built, shaven-headed, African, and gorgeous; and Jenn all sinew and attitude, hair cut like a boy’s and tan from a summer of intense soccer practice. These three were sitting in the bleachers set back from an outdoor stage upon which a group called the Time Benders was about to begin performing.

It was Saturday night, the night that drew the most people to the fairgrounds because it was also the night when the entertainment was, as Jenn put it, “marginally less suicide-inducing than the other days.” Those other days the entertainment consisted of tap dancers, yodelers, magicians, fiddlers, and a one-man band. On Saturday night an Elvis impersonator and the Time Benders comprised what went for the highlight of the fair.

For Becca King, with a lifetime spent in San Diego and just short of one year in the Puget Sound area, the fair was like everything else she’d discovered on Whidbey Island: something in miniature. The barn-red buildings were standard stuff, but their size was minuscule compared to the vast buildings she was used to at the Del Mar racetrack where the San Diego County Fair took place. This held true for the stables for horses, sheep, cattle, alpacas, and goats. It was doubly true for the performance ring where the dogs were shown and the horses were ridden. The food, however, was the same as it was at county fairs everywhere, and as the Time Benders readied themselves to take the stage after Elvis’s final bow during which he nearly lost his wig, Becca and Derric and Jenn were chowing down on funnel cake and kettle corn.

The crowd, who turned up to watch the Time Benders every single year, was gearing up its excitement level for the performance. It didn’t matter that the act would be the same as last August and the August before that and the one before that. The Time Benders were a real crowd pleaser in a place where the nearest mall was a ferry ride away and first-run movies were virtually unheard of. So a singing group who performed rock ’n’ roll through the ages by altering their wigs and their costumes and re-enacting the greatest hits of the 1950s onwards was akin to a mystical appearance by Kurt Cobain, especially if you had any imagination.

Jenn was grousing. Watching the Time Benders was bad enough, she was saying. Watching the Time Benders at the same time as being a third wheel on “the Derric-and-Becca looove bike” was even worse.

Becca smiled and ignored her. Jenn loved to grouse. She said, “So who are these guys, anyway?” in reference to the Time Benders as she dipped into the kettle corn and leaned comfortably against Derric’s arm.

“God. Who d’you think?” was Jenn’s unhelpful reply. “Y’know how other county fairs have shows where has-been performers give their last gasp before they finally hang it up and retire? Well, what we got is unknown performers re-enacting the performances of has-been performers. Welcome to Whidbey. And would you stop feeling her up, Derric?” she said to their companion.

“Holding her hand isn’t feeling her up,” was the boy’s easy reply. “Now if you want to see some serious feeling up . . . ?” He leered at Becca. She laughed and gave him a playful shove.

“I hate this, you know,” Jenn told her friend. She was returning to the previous third-wheel-on-the-looove-bike topic. “I shoulda stayed home.”

“Lots of things come in threes,” Becca said.

“Like what?”

“Well . . . Tricycle wheels.”

“Triplets,” Derric said.

“Those three-wheel baby buggies for joggers who need to take their kids with them,” Becca added.

“Birds have three toes,” Derric pointed out. Then, “Don’t they?” he said to Becca.

“Great.” Jenn reached for more funnel cake and jammed it into her mouth. “I’m a bird toe. Lemme send that out on Twitter.”

Which would, of course, be the last thing Jenn McDaniels could have done, since among them Derric was the only one who possessed anything remotely close to technological. Jenn had neither computer nor iPhone nor iPad nor laptop, because her family was too poor for anything more than a third-hand color television the size of a Jeep, practically given away by the thrift store in town. As for Becca . . . Well, there were a lot of reasons why Becca remained at a distance from technology and all of them had to do with keeping a profile so low that it was invisible.

The Time Benders came forth at this point, climbing onto the stage past amplifiers that looked like bank vaults. Their wigs, pegged pants, white socks, and poodle skirts indicated that—just like last year—they’d be starting with the fifties. The Time Benders never worked in reverse.

The crowd cheered as the show began, lit by the rest of the midway with its games of chance and its creaking thrill rides. The best of the fifties blasted forth at maximum volume. Over the noise, Jenn shouted at Becca, “Hey, you probably won’t need that thing.”

That thing was a hearing device that looked like an iPod in possession of a single ear bud. It was called an AUD box and, despite what Jenn thought, Becca didn’t use it to help with her hearing. At least not in the way Jenn thought she used it. Jenn and everyone else believed that the AUD box helped Becca understand what was being said to her by blocking out nearby noises that her brain wouldn’t automatically block: like the noise from other tables that you might hear in a restaurant but normally be able to ignore when someone was talking to you. That was what Becca let people believe about the AUD box because it did, actually, block out some noise. Only, the noise it blocked was the noise inside the heads of the people who surrounded her. Without the AUD box she was bombarded by everyone’s thoughts, and while hearing people’s thoughts could have its benefits, most of the time Becca couldn’t tell who was thinking what. So since childhood, the AUD box was what she wore to deal with her “auditory processing problem,” as her mom had taught her to call it. Thankfully, no one questioned why the AUD box’s loud static helped her in understanding who was speaking. More important, no one knew that without it, she was one step away from reading their minds.

Becca said, “Yeah, I’ll turn it down,” and she pretended to do so. Up on the stage, the Time Benders were rocking and rolling through “Rock Around the Clock” while on either side of the stage, some of the older audience members had begun to dance in keeping with the music’s era.

That was when the first gust of smoke belched across the heads of the crowd. At first, it seemed logical that the smoke would be coming from the line of food booths, all doing brisk sales of everything from buffalo burgers to curly fries. Because of this, the Time Benders audience didn’t take much note. But when there was a pause in the music and the Time Benders were getting ready for the sixties with a change of costumes and wigs, the sirens hooting from the road just beyond the fairgrounds’ perimeter indicated something serious was going on.

The smell of smoke got heavier. People started to move. A murmur became a cry and then a shout. Just at the moment that panic was about to set in, the regular MC for the show took the stage and announced that “a small fire” had broken out on the far side of the fairgrounds, but there was nothing to worry about as the fire department was there and “as far as we know, all animals are safe.”

The last part was a serious mistake. “All animals” meant everything from ducks to the 4-H steer lovingly brought up by hand and worth a significant amount of money to the child who would sell it at the end of the fair. In between ducks and steers were fancy chickens, fiber-producing alpacas, award-winning cats, sheep worth their weight in wool, and an entire stable filled with horses. Among the audience for the Time Benders were the owners of these animals, and they began pushing their way in the direction of the buildings in which all the animals were housed.

In short order, a melee ensued. Derric grabbed Becca and Becca grabbed Jenn, and they clung to each other as the crowd surged out of the midway and past the barn where the crafts were displayed. They burst out behind it into an open area that looked onto the show ring and to the buildings beyond.

At the far side of the show ring, the stables were safe. The fire, everyone saw at once, was opposite them on the side of the show ring that was nearer the road into town. But this was where the dogs, cats, chickens, ducks, and rabbits had been snoozing in three ramshackle sheds that flaked old white paint onto very dry hay. The farthest of these sheds was up in flames. Fire licked up the walls and engulfed the roof.

The fact that the fire department was directly across the street from the fairgrounds had the effect of getting manpower to the flames in fairly short order. But the building was old, the weather had been bone dry for nine weeks—almost unheard of in the Pacific Northwest—and there were hay bales along the north side of the structure. So the best efforts of the fire department were directed toward keeping the fire away from the other buildings while letting the one that was burning burn to the ground.

This wasn’t a popular move. There were chickens and rabbits inside. There were dozens of 4-Hers who wanted to save those animals, and the news that someone had apparently released them at some time during the fire only made the onlookers crazed to get to them before they all got trampled. Soon enough there were too many fire chiefs and too few onlookers and enough chaos to make Derric, Jenn, and Becca head for the safety of the stables some distance away.

“Someone’s going to get hurt,” Becca said.

“It ain’t going to be one of us,” Derric told her. “Come on, over here.” He took her hand and Jenn’s, and together they made their way beyond the stables to where a woods grew up the side of a hill to a neighborhood tucked back into the trees. From this spot they could watch the action and listen to the chaos, and while they did this, Becca removed the ear bud from her ear and wiped her hot face.

As always, she heard the thoughts of her companions, Jenn’s profane as usual, Derric’s mild. But among Jenn’s colorful cursing and Derric’s wondering about the safety of the little kids whose parents were trying to keep them away from the fire, Becca heard quite clearly, Come on, come on . . . get it why don’t you? as if it was spoken right next to her.

She swung around, but it was dark on all sides, with the great fir trees looming above them and the cedars leaning heavy branches down toward the ground. At her movement, Derric looked at her and said, “What?” and then shifted his gaze into the trees as well.

“Is someone there?” Jenn asked them both.

“Becca?” Derric said.

Out of here before those kids . . . was enough to give Becca the answer to those questions.

Hayley Cartwright looked around for her sister Brooke, who’d claimed that she was leaving the family’s booth at Bayview Farmers’ Market just long enough to do her business in the rest room. Total lie. She’d been gone thirty minutes, leaving Hayley and her mom to run the booth all by themselves when it was, minimally, a three-person job. Brooke did the bagging and the weighing of veggies, Hayley wrapped the flowers and boxed the jewelry, and their mom took the money and made change. But with Brooke gone, Hayley was left dancing from one side of the booth to the other and trying to keep her eye on everything but especially upon the jewelry, which was fashioned from sea glass, difficult to make, and her main source of personal income.

Not that people actually shoplifted from the Cartwrights, at least not people who knew them. Taking even a dime from the Cartwrights was close to the same as emptying the family’s pitiful bank account, and everyone on the south end of Whidbey Island who knew the family also knew that. So most of the time people lined up patiently to pay for the flowers and veggies that the Cartwrights grew at Smugglers Cove Farm and Flowers. They chatted to each other in the warm early September sun, petted the myriad dogs who accompanied the market-goers among the colorful stalls, and listened to the music weekly supplied by one or another of the local marimba bands.

This day, though, a girl unknown to Hayley had been pawing through her necklaces, bracelets, earrings, and hair pieces for at least ten minutes. She’d also been trying them on. She was very pretty, with a swimmer’s broad shoulders and shapely arms and legs that were on full display beneath her tank top and shorts. She wore her hair in an odd Cleopatra style—if Cleopatra had been extremely blonde—and her bangs dipped almost into her eyes, which were so cornflower blue that only colored contact lenses could have achieved the hue.

She saw Hayley watching her as she was putting a third necklace around her ivory-skinned throat. She’d already donned four of the bracelets, and she was reaching for one of the more complicated pairs of earrings quite as if there was nothing strange about decking herself out like a jewelry tree.

Seeing Hayley observing her, she said, “I c’n never decide a single thing when I’m by myself. It’s absolute murder if I’m trying on clothes. My grandam is here somewhere”—here she looked around the crowded market distractedly—“and I guess I could ask her, but she’s got the most wretched taste, which you’d more or less have to expect from someone who carves up trees for a living. Not that there’s anything wrong with carving up trees, mind you. I’m Isis Martin, by the way. Egyptian. I mean the name is, not me. Isis was the goddess of something. I can never remember what but I truly hope she was the goddess of hot desire because I’ve got a seriously delicious boyfriend back home. Anyway, what’re these made of and which do you think looks best on me?” During all this, she’d put on a fourth necklace, odd because she was already wearing her own, a gold chain with elongated links that disappeared into her tank top and must have cost a fortune. She was peering into the stand-up mirror that Hayley provided, and she paused in her inspection of Hayley’s necklaces to put on lipstick that she excavated from a basket-weave purse.

Hayley liked the purse but was afraid to say this, for fear of setting the girl off again. So she said, “It’s sea glass. I make them. I mean, I make all the jewelry.”

“Sea glass?” Isis said. “You mean ‘sea’ like from the ocean? So do you get it from . . . like . . . I mean, are you a diver? I tried to learn to dive. My boyfriend before my current boyfriend? He and his family were into diving in a major way and they took me to the tip of Baja for spring vacation one time? They tried to help me learn to dive, which was a total joke because I am so, like, totally claustrophobic.”

“I find it on the beach,” Hayley told her when Isis took a breath. She looked over the other girl’s head to see if Brooke was anywhere in view. No such luck, which meant she had to get back to bagging and weighing. She glanced over her shoulder. The line of patient shoppers was extending and her mom was beginning to bag and weigh. She looked harried. She cast Hayley a supplicating glance.

“On the beach? Way cool,” Isis said. She reached for a fifth necklace. “I love the beach. Maybe I could go with you sometime? I’ve got a car. Well, my parents had to give me something to come up here, after all. I wouldn’t be any good at looking for sea glass, though. I’m blind as a whatever without my contacts and I generally don’t wear them at the beach because of the sand and how it can blow into your eyes if you know what I mean.”

“It’s over past Port Townsend,” Hayley told her. “The time to find it is winter, after a storm, more or less.”

“What’s past Port Townsend?” Isis peered at her reflection, then laughed. “Oh, I bet you mean the beach where you get the glass. God, I’m a flake. I c’n never remember what I’m talking about. Where’s Port Townsend? Should I go there? D’they have any decent shops?” She handed Hayley a sixth necklace, one that she hadn’t tried on. She picked one of the bracelets already on her arm along with a pair of earrings she’d not inspected and a barrette that matched nothing at all. “I think this’ll do it. Did you tell me your name? I can’t remember. I am such a ditz.”

She began disentangling the rest of the necklaces she’d donned as Hayley said that her name was Hayley Cartwright and, yes, Port Townsend had some really cool shops, if you could afford them. Hayley herself couldn’t, but she didn’t add that. She just wrote up the sale of the necklace, bracelet, earrings, and barrette, and she helped the other girl remove from herself everything else she’d donned. She told Isis the price, and the girl dug a thick wallet out of her woven purse. It was crammed with all sorts of things: newspaper clippings, folded notes with scribbles all over them, coffee reward cards, pictures, and cash. A great deal of cash. Isis pulled out a wad of it and distractedly handed it over.

She said, “Could you . . . ? Just take what you need.” Then she laughed. “I mean take what I owe you!” And she fixed the new necklace around her neck and scooped up some of her hair behind the barrette. She did this latter action with a lot of skill. She might be bird-brained, Hayley thought, but when it came to her appearance, she knew what she was doing.

Hayley counted out the appropriate amount of money and handed the rest back. Isis was admiring the barrette in her hair. The sea glass around her neck, as it turned out, was an inspired choice. It exactly matched the color of her eyes.

Isis took the rest of the money and crammed it into her wallet. She had a section of pictures inside this that was three fingers thick. She said, “Oh, you’ve got to look at him,” and flipped open to the first. “Is he totally hot or what?” She showed Hayley a picture of a boy whose hair stood out from his head in a way that made him look like a cartoon character recently electrocuted.

“Uh . . . he’s . . . ?” Absolutely nothing came into Hayley’s mind.

Isis laughed in delight. “He doesn’t really look like this. He just did that to piss his parents off.” She shoved the wallet back into her purse. “Hey, d’you want to get a lump-whatever? I can’t remember what it’s called but there’s a lady over there selling them and they look totally like something I shouldn’t be eating in a million years. Which, of course, is why I fully intend to buy two or three. What are they called?”

Hayley laughed in spite of herself. There was something beguiling about Isis Martin. She said, “Lumpia?”

“That’s it. I can tell I need you to help me navigate these mysterious island waters. I’ve been here since June. Did I tell you that? Me and my brother . . .” She rolled her eyes expressively, and at first Hayley thought this was in reference to her brother until Isis made the correction with, “My brother and I. Grandam goes berserk when I say ‘me’ as the subject of a sentence, so sometimes I do it on purpose. She thinks I don’t know it should be I. Well, I’m a congenital idiot, but I do know me is an objective case pronoun, for heaven’s sake. So d’you want a lumpia or two or six?”

Hayley said, “Sorry. I can’t leave . . .” She waved around her. “The booth, you know. My sister’s supposed to be here, but she’s disappeared.”

“Siblings. What a trial. Well, maybe another time?”

“You go on, Hayley.” It was Hayley’s mom speaking. She’d been on the edge of the conversation all along. “I can handle things here. Brooke’ll be back.”

“It’s okay. I don’t—”

“You go, sweetheart,” her mom said firmly.

Hayley knew what that meant. Here was an opportunity to be “just a kid,” and her mom wanted her to have that opportunity.

• • •

BROOKE FINALLY SHOWED up when they were disassembling their booth and getting ready to drop the unsold veggies at the nearby food bank, a feature of the island that most visitors to Whidbey didn’t know about. Tourists to the island came to soak up the atmosphere: the razor-edged bluffs rising up from beaches studded with sea shells and jumbled with driftwood, the pristine waters where a crab pot brought up fifteen Dungeness within two hours, the deep forests with shadowy hiking trails, the picturesque villages with their clapboard, seaside charm. As to the homeless population and the needy families . . . To visitors, they remained unseen. But people who lived on the island didn’t have to look far to find people in need, because many of them were neighbors, and when Brooke groused about how “totally dumb it is to be giving our food away when we should be selling it somewhere and making some money,” their mom cast a look into the rearview mirror and said to her, “There are actually people worse off than we are, sweetheart.”

Brooke’s response of “Yeah? Name ’em,” was out of character. But a lot of her remarks had been out of character lately. Their mom called this a stage that Brooke was going through. “The middle school years. You remember,” she said to Hayley as if Hayley had also been a Mouth with Attitude when she’d been thirteen. Hayley, on the other hand, pretty much believed that Brooke’s attitude had nothing to do with middle school at all. It had, instead, everything to do with the Big Topic that no one in their family would ever discuss.

Their dad, Bill Cartwright, was falling apart. It was a slow process that had begun in his ankles and had now worked its way up his legs so that they didn’t do what his brain asked them to do any longer. Time was when their dad would have been with them at the farmers’ market, working the booth. Time was when he would have shared the labor at Smugglers Cove Farm and Flowers, too. Hayley’s mom would have been raising the horses that she no longer raised and growing the flowers while he raised goats and worked in the huge vegetable beds as the girls took care of the chickens. But that time had passed, and now what went on at the farm was whatever the women could manage, minus the littlest Cartwright woman, Cassidy, who was only competent at collecting eggs. What couldn’t be managed by the women simply no longer occurred on the farm, but no one mentioned anything about this or anything about doing something that might help them out. It was, Hayley thought, an extremely dishonest way to live.

They were heading north on the highway on the route home, when Julie Cartwright asked Hayley about “the chatty girl who bought the jewelry.” Who was she? A day-tripper from over town? A vacationer? Someone from school? A new girl friend, perhaps? She didn’t look familiar.

Hayley heard the hopefulness in her mom’s voice. It had two prongs. The first was to change the topic of conversation in order to alter Brooke’s mood. The second was to direct Hayley toward getting a normal life. She told her mom that the girl was Isis Martin—

“What kind of weirdo name is that?” Brooke demanded.

—and she’d been on the island since June. She lived with her grandmother and her brother and . . . Hayley realized that despite all of Isis’s chatting, those were actually the only two facts she knew aside from her having a boyfriend. Isis had bought four lumpias and, cleverly, had decided that she could only eat two of the pastry-like stuffed delicacies. She’d handed the other two over to Hayley, saying, “Do me a fave and snarf these, okay.” It had been breezily done. Hayley had found herself liking the girl for doing it.

After eating and when Hayley had said she needed to get back to the market stall, Isis had scribbled down her smart phone number and handed it over. She’d said, “Hey, maybe me and you c’n be friends. Call me. Or text me. Or I’ll call you. We can hang. I mean, if you c’n put up with me.” She’d excavated in her straw purse for an enormous pair of sunglasses with rhinestones along the ear pieces, saying, “Aren’t these the trippiest ever? I got them in Portland. Hey, give me your number, too. I mean, if I haven’t totally put you off with my babbling. It’s ADD. If I take my meds, I’m more or less focused, but when I forget . . . ? I’m a verbal shotgun.”

Hayley had given the other girl her phone number, although her cell phone was as basic as they got, so there would be no texting. She also told her the family phone number to which Isis had said, “Wow, a land line!” as if having this was akin to having kerosene lamps.

“Anyway,” Hayley said to her mother, “she was sort of ditzy, but in a good way.”

“How lovely,” Julie Cartwright said.

When they arrived at Smugglers Cove Farm and Flowers and trundled up the long driveway toward the collection of barn-red buildings, they found Hayley’s dad on the front porch along with Cassidy. They were on the swing looking out at the farmyard. Cassidy had a death grip on one of the barn kittens. Bill Cartwright had a similar grip on the chain from which the swing did its swinging.

He struggled to his feet, and everyone did their usual thing of pretending not to notice. This was becoming progressively more difficult since he had begun using a walker. He worked his way to the edge of the porch as his women clambered out of the car. He called out, “Hayley, would you get that young man out of the vegetables? He wouldn’t take no for an answer,” which made Hayley look in the direction of the vegetable beds stretching out gloriously with the beginning of the autumn harvest.

She saw Seth Darrow’s 1965 VW before she saw him. The restored bug was parked to one side of the barn. Seth himself was crouched at the near end of the sweet potatoes. He had to be dealing with the watering system, she decided. They’d been having trouble with it all summer and he must have stopped by the farm, had a conversation with her dad during which the watering system had come up. It would be just like Seth to set off to deal with it.

“I tried to tell him I’d be getting to it tomor

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...