- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

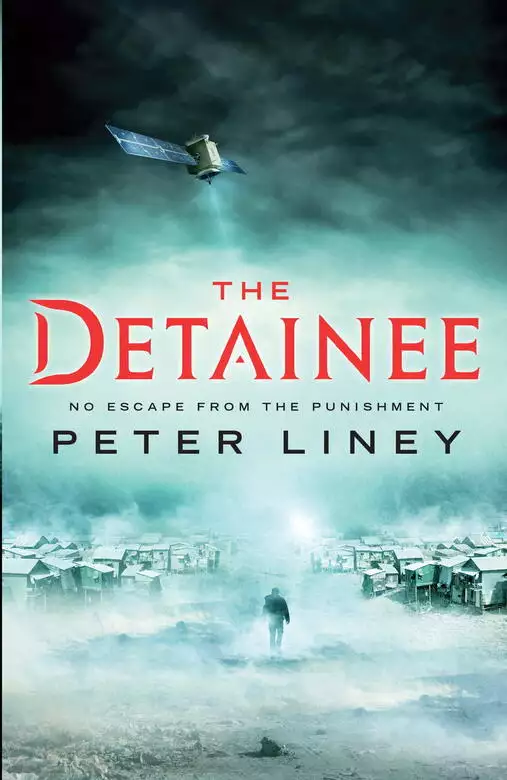

Synopsis

‘I never thought it would come to this, never in my worst nightmares. No matter how bad things got, how much the government warned us, I still thought we'd be okay.'

When the fog comes and the drums start, the inhabitants of the island tremble: for the satellites are blind in the darkness, and the islanders become prey. The inhabitants are the old, the sick, the poor: dumped on the island with the rest of Society's waste. The island is the end of all hope, until Clancy finds a blind woman living in a secret underground warren, and discovers a reason to fight.

Release date: July 4, 2013

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Detainee

Peter Liney

If you’ve never heard that scream, I hope for your sake you never will. I, on the other hand, must’ve heard it a thousand times. I can hear it now. A woman somewhere over towards the rocks is squealing like an animal that’s just realised it exists to be butchered, her cries issuing out of the fog like blood through a bandage. Now some guy, probably her partner, has joined in. Shouting at them, telling them to leave her alone, as if he has some influence on the situation. But you know he hasn’t. Fear’s slicing so hard at his voice it’s cutting right through. Soon she’ll die, and so will he. And I can do nothing but lie here in the dark, listening to my frightened heart pounding; just as all around me, hundreds of others must be lying there, listening to their frightened hearts pounding. It makes you feel sick to do it. But we don’t seem to have a choice.

*

If I could have one wish in life, do you know what it would be? Do you? To be young again. To be thirty, no, shit, forget it, twenty-one. Oh yeah, I know, ‘Age brings wisdom; each age has its own compensations.’ That ain’t nothing but shit. Nothing but whistling into the grave. There ain’t no dignity in getting old. Ain’t no honour in being forever sick and your body rotting and being reluctant to mend with you. And I’m weak, too. My muscles hang off my bones now like they’re melting, like they’re wanting to ooze on down to the floor. Once I could’ve shifted anything. Anything or anyone that stood in my way, no problem.

Not that I was mean. I worked for some mean sonsofbitches but I didn’t do that much myself. Just the sight of me was usually enough. This big, wide bastard, with a face off the side of a cliff, erupting with muscle. I was Vesuvius with muscle to burn. You’d see me come in through the door, blocking all the light and you’d say: ‘Yes, sir, whatever you say, sir. It’s a pleasure doing business, sir. But don’t set that big bastard on me.’

Truth was, I was more of an actor than anything. A frightener. But I was strong if I had to be. Twenty, maybe fifteen years ago I could’ve taken hold of this sack of old bones wherein clanks my weary heart and crushed it like a bag of broken cookies. So don’t you believe any of this shit they give you about getting old. ’Cuz the truth is, it makes you want to weep, it makes you want to cry for the health and strength you once had. Nowadays, if I look in a mirror, there’s this old guy staring back at me. I don’t know him. His skin’s a size too big for his bones, his hair’s all dry and drained of colour, and there ain’t the slightest flicker left in those sad flat blue eyes. In short, he’s old. And for old read helpless. Read unable to stop all these terrible things that’ve been going on round here.

*

Jesus! What the hell was that? What are they doing to her to make her scream that way? … Leave her alone! For chrissake. Let her be. Block it out, that’s the thing. Seal off all the entrances and don’t let anything or anyone through. Just me in here, inside this tortured old head, surrounded by barricades of fading and fragile memories.

Maybe if I was to share them with you? Pass them on before they dry right up and blow away? Maybe it would help you understand how we all ended up living like this.

*

How far back do you want me to go? The past seems so far away now. I won’t bore you with my childhood. I remember only one thing about my old man: on Saturday nights he’d come home stumbling drunk and either start serenading my mother like a fool, or laying into her like a madman. A combination she apparently found irresistible, ’cuz when he died in his sleep one night she refused to admit it to anyone. Just carried on, getting up, going about her usual business, even sleeping with the body. I tell you, if it hadn’t been for me going in there one morning, jumping up and down on his blotched and bloated hide, this terrible stench suddenly ripping out of him, he’d probably still be there now.

It’s a sad thing to have to tell you, but, for myself, I never actually been married. Never even had a proper relationship. Don’t ask me why. I used to have a perfectly respectable career, working for one of the classiest criminals around, but do you know something, the big guy never gets the girl. Have you ever noticed that? It’s the same in the movies. Mind you, the movies are pretty unkind to us all round: the big guy’s always stupid, the dope who never gets the joke. My theory is that it’s little guys who make movies.

*

She’s making a run for it. Shrieking at the top of her voice, tripping over in the dark with them chasing along behind her. Laughing and teasing in that way they do, working themselves up for the kill. The man’s voice stopped some time ago. They must’ve finished him off already. Please. Don’t come this way, lady. I hate myself for saying it, but don’t come over here to do your dying.

*

Where was I? … Oh yeah. All this talk about the past, about getting old, you won’t be surprised to learn I’m an Island Detainee. Got sent out here almost ten years ago after being means-tested and found wanting. I have this little lean-to, in the middle of the Village, out towards the eastern shore. It ain’t a lot, just a few planks and some sheets of plastic, but it’s as much as any of us can hope for now. Damp, of course, which don’t go down well with my chest. And cold in winter, too. There’s a special kind of cold seeps off that ocean, like it’s being injected into your bloodstream by icicles.

Then there’s the rats. Thousands of them. I tell you, some days it looks like the whole island’s on the move. Bold as brass, too. They don’t take the blindest bit of notice, no matter what you shout or throw at them. All you can do is look on them as your fellow creatures, living, not so much alongside, as with you. Sharing your home, your food, sometimes even your bed. If you don’t, it’ll drive you crazy.

I guess that makes things sound pretty bad. Endless rows of makeshift lean-tos lurching this way and that, acres of sheets of multicoloured plastic flapping like tethered birds, flies constantly trying to suck the juices from your mouth and eyes. But that ain’t the worst of it. That ain’t the worst by far. The worst bit is the smell.

They say you get used to it in the end, but even now, after all this time, there are days when I feel nauseous right from the moment I get up ’til the moment I go back to bed. Sometimes I even wake in the middle of the night, retching, spilling my dry guts out across the ground.

A lot of it depends on the weather. Top of the summer, when it’s stifling and still, it’s more than you can bear. There’s a constant sweet and sickly fug so thick it’s like someone jamming their dirty fingers down your throat. It ain’t something I can truly do justice to, but if you’ve ever smelled a dead animal rotting on a hot summer’s day, well, times that by a hundred, by a thousand, and you’ll have some idea.

Garbage. Nothing but garbage. Acres and acres, heaped up, stretching and stinking into the distance like a flyblown corpse dried and contorted by death. Most has been combed out, dragged and checked for anything of value, then just left to rot. Year in, year out, ’til it subsides enough to be tipped on again – and again, and again.

Some places, you dig down deep enough you’ll come across the twentieth century. Antique garbage and, believe it or not, there are those willing to excavate for it. Course it’s dangerous. You gotta wear a mask. But that ain’t much in the way of protection from what’s down there. Cancer ain’t nothing on the Island. Dead cancer, walking cancer, distended bulges and weeping sores. We don’t even think of it as a disease anymore. Just a parasite. Like those flies you got to keep an eye on in case they try to lay their eggs in your cuts and grazes.

*

Thank God, it’s over. Death has come to death and left nothing at all. Just the dark emptiness of the fog, holding us in, keeping us prisoner, whilst allowing them to go free.

At least it was quick, that much I’ll give them. I’ve known nights it’s gone on ’til almost dawn. Screams running back and forth, stopping, starting up again, like their victims are being tortured to the point of death and then just held there.

Though the worst part is when someone begs you to help. When they stand outside your lean-to squealing for you to come out and save them. Can you imagine how that feels? To someone like me? Once I might’ve been able to do something. But not now. Not against them. I wouldn’t stand a chance.

*

When I was young and used to see homeless old people hanging round, I never dreamed I would end up being one myself one day. Why would I? I was healthy, strong, and once I started working for Mr Meltoni, always had plenty of money. And there ain’t nothing like a pocketful of dough and some bounce in your stride to make you think you’re gonna live forever. In any case, everyone always assumed it was gonna get better, not worse. But it’s those with a home who are the exception now. Those across the water, behind their fortified walls, in their private enclaves, who make all the rules and who decided that by sending us out here, by giving us this ‘last chance to become self-sufficient’, they’d done everything for us they could. Which, in case you don’t know, is how we ended up living on this dollop of crap; four miles long, three across and a little over a mile offshore.

Once it used to be a residential island, part of the commuter belt, the Island Loop, but somewhere along the line someone decided it was the ideal place to start offloading the Mainland’s waste. Gradually, over the years, with garbage mounting up and threatening to topple back over everyone, it became less of a residence and more of a dump. ’Til finally, almost thirty years ago, the last inhabitants were forced to abandon it to its rotting fate.

I guess it never occurred to anyone then that it would be lived on again. I mean, it ain’t fit for purpose. But there are thousands of us out here. Mostly old people, those with no money, who once might’ve thought they’d be taken care of. However, no one takes care of you anymore. You either survive or die, simple as that. Sure as hell the State don’t. They can’t afford to look after anyone. And do you know who they say’s to blame? Not incompetent and corrupt politicians, not those pigs gorging themselves down at the stock exchange trough, but us. Old people. Old people ’cuz we got too old. As if we had a choice.

Most of the country’s population’s over seventy. The social safety-net gave way long ago – not enough young people putting in, too many old people taking out – so it’s our fault ’cuz we didn’t look out for ourselves. Well, I’ll tell you something, I thought I did. Mr Meltoni always insisted on me putting away a little something every month in a pension fund.

‘Look after yourself, Big Guy,’ he used to say. ‘’Cuz no one’s going to do it for you anymore.’

And do you know something? He got it right. Unfortunately though, the pension companies got it wrong. After everything that happened, all the problems we had with banks and the financial system at the start of the century, they still put everything on the market. Can you believe that? An entire society’s future. All it took was one tiny whisper on the Internet saying they’d got their sums wrong, the advances in medical science meant their clients would be drawing pensions a lot longer than they thought, and the whole thing came tumbling down. Not just the market, not just the pension companies and the banks backing them, but this time everything else, too.

I mean, you couldn’t believe it. This structure we knew as society … civilisation … everyday life … that we thought of as permanent and beyond question, just collapsed around us in a matter of weeks.

*

‘Big Guy!’

Jimmy’s slightly quavering voice, just outside my lean-to, suddenly woke me, and I realised that, no matter how tortured the night, I must’ve finally fallen asleep.

‘Big Guy, you in there?’

Jimmy’s this little gnome-like character, bent and big-nosed, with a few tufts of white hair on the sides of his freckly bald head that he likes to strain back into a ponytail and a limp that has no story to it. He just woke up one morning and there it was. Later he tried to make up some tale about how he got it – that made him look good – but we all know, as does he, that it’s just another symptom of getting old.

He did try a faith healer for a while (there ain’t no real doctors on the Island, leastways not for us). For ages he went round with this moss poultice strapped to his leg, well after it had dried up and gone all brown. But it didn’t do him any good. Now, when it starts to give him problems he has to use a stick.

I’ve known Jimmy almost all the time I been out here. I like him, he knows when to back off. I don’t even have to say nothing. I just give him the look, and he’s gone.

‘Big Guy!’

‘Okay,’ I grunted. ‘I’m coming.’

I heaved myself out of my pit and into a morning cold, clear and, thankfully, free of fog. Jimmy was standing there with that slightly shifty expression on his face that means he’s about to ask me for something and doesn’t know how I’ll react.

‘Did you hear?’

I nodded. He knew I heard. Everyone had.

He paused for a moment. ‘Would you er … Would you mind … giving me a hand?’

I sighed long and hard, which he took to mean I had no strong objections, and turned and limped away, expecting me to follow.

For a few moments I just stayed where I was, feeling a little put upon, that he was being presumptuous as usual, then I reluctantly tagged along behind.

We made our way down the long line of lean-tos, Jimmy stealing a quick look at his place opposite to make sure he hadn’t been seen, then taking a turning towards the ocean, along another line and in the direction of last night’s screams.

Soon we reached a lean-to where the plastic had been wrenched from its frame and used to cover something on the ground. It didn’t take a genius to work out what.

‘I came over earlier. Made a real mess of them,’ he said grimly.

I lifted the plastic and peered underneath. He was right. A couple I vaguely recognised had been hacked to death, the final cuts to behead them. I turned away and let the plastic fall from my hand. You just can’t believe it. It’s like a shock that goes on forever. Hard enough to take in what’s being done, let alone who’s doing it.

‘Jesus,’ I muttered.

Jimmy nodded. ‘I just think, you know … you can’t just leave them here.’

I sighed. He was right – someone had to do their ‘civic duty’ – though knowing him, I was pretty sure he had some kind of ulterior motive.

Taking care not to lose anything out of the ends, we rolled the bodies up into the plastic and dragged them off in the direction of the corrosives pool. Where nobody, nor anything else for that matter, lasts for more than a couple of hours.

All along the way, eyes much older and more weary than mine stared out of the darkened insides of their lean-tos. Yet no one spoke, no one asked what happened. It’s as if the longer we live like this, with no meaning or structure to our lives, the more we regress to what we’ve always been: dumb animals. Eating when we can, sleeping when we can, mutely accepting those who occasionally come to cull this sickly old herd.

I tell you, some days it makes me so mad I want to run around and smash every lean-to I can down to the ground. Just to make them react, to make them say something for once, but instead I become more and more insular, more bad-tempered, more a person that, I know, most Villagers go out of their way to avoid.

We reached the corrosives pool accompanied by a mob of flies that knew there was a banquet somewhere, but weren’t exactly sure where. The woman’s head fell out as we were unwrapping the plastic and Jimmy looked away as I toe-poked it down the slope. Almost the instant it hit the waiting greenish liquid you could see the flesh starting to pucker away from the bone. It was like some creature we fed, devouring everything we gave it yet always hungry for more.

For a few moments we stood and watched as the two headless torsos slipped out of sight and existence, then Jimmy turned and, with a sudden sense of purpose, began to peg it back towards the Village, unconcerned that he was leaving me some yards behind.

Along the way, from the top of one of many mountains of garbage, I could see almost the entire island. The vomited sprawl of the Village, the ruins of the Old City, and in the distance the pier where the garbage boats come in every day (actually, it’s not a ‘pier’, but all that remains of the bridge that used to stretch out here from the Mainland. It was demolished one foggy night by a tanker, and, as a matter of convenience, never rebuilt). Down in the Camp they had their usual fire going, its rising column of black smoke circling round the Island like some huge snake slowly choking the life out of us.

Of all the hells that humankind’s ever created, this is surely one of the worst. Nothing but mile after mile of waste, discharge and debris; the ass-end of civilisation. And we’re left choking in its shit, just as one day, you suspect, everyone else will have to do the same.

I turned and looked across towards the Mainland. There was still a layer of last night’s fog lingering in the bay and the city rose up out of it like an orchestra; its walls rinsed pink by the early-morning sun. That new building certainly does dominate. Jimmy reckons it belongs to one of the utility companies, but I’m not so sure. Whatever, it’s the major piece on the chessboard. I mean, it could be Heaven. Or maybe the Promised Land. Not that I’m saying I envy what they got over there – I don’t. They can keep their wealth, their warmth, and their privileged lives. I don’t even care that they don’t have to worry about who comes for us on a dark foggy night. There’s only one thing they got I want. Mind you, I want it so badly, sometimes it feels as if, deep inside me, I’m crying out for it every moment of the day and night.

I want to be allowed to go free. To get off this foul and sickening pile of crap, fill my lungs with fresh air, my heart with hope and believe in people again.

But I might as well sit and howl for the moon. No one’s ever got off the Island. No one. They seen to that good and proper. Once you’re out here, the only way you leave is by dying. By the wings of your spirit lifting you up and flying you out of this godforsaken place.

For the rest of the day everyone in the Village kept a real close eye on the weather. The sun’s always appreciated at this time of year, giving a bit of relief to old and creaking joints – like a squirt of warm oil. But the fact that it means the fog might return later, and that it might bring them with it, is another matter.

I remember someone explaining to me once why it is we get so much fog out here. Something to do with currents and land mass – I don’t know, I wasn’t really listening. All I do know is that, during some periods of the year, you can go for a week without seeing the Mainland. It’s strange, almost as if they’ve managed to cut us loose. The world goes on spinning whilst we’re cast adrift in some silent grey pocket of sodden space. Out of sight, out of mind, and by inference, everything that happens to us out here happens with their blessing.

On the way back from dumping the bodies, Jimmy made some excuse and headed off on his own. I wasn’t altogether surprised when later he came struggling up the row with an armful of junk he’d obviously taken from the victims’ lean-to.

‘I should’ve guessed,’ I grunted, immediately realising that this had been his ulterior motive for helping to move the bodies in the first place.

‘Got some really cool stuff,’ he told me, indicating the large box that, despite his walking stick, he was still managing to carry.

He angled it towards me so I could look inside and I caught a glimpse of a load of odds and ends that it would be optimistic to call junk: part of an old radio, a metal tube, lengths of wire. God knows what he’s going to do with it.

I just nodded. It’s not exactly an unwritten law, but having cleared up the bodies, I guess he had every right to be the first to sort through their stuff – and he knows I wouldn’t be interested.

He tossed the box down into the entrance of his lean-to and turned to head back for some more. He hadn’t got more than a dozen paces before Delilah came rushing out.

‘Jimmy! What the hell’s this?’ she shouted, taking a heavy kick at the box.

The little guy hunched up his shoulders, lowered his bald head into them like some shy turtle and limped on as if he couldn’t hear a thing. Though, if he couldn’t, he was about the only person this side of the Island.

‘Jimmy!’

Delilah’s Jimmy’s companion. I would say lover, but I think companion’s more accurate on account of the fact that they keep a great deal of company, but don’t show a lot of love. She’s this great long, twisted stick of a woman, so thin you wouldn’t think she had the strength to stand, but actually she’s as tough as old nails. If the human race ever reached a point where the genes of every nationality were poured into one person, I reckon they’d be in her. Her complexion’s that browny-grey colour you get when you’ve been mixing too many paints together and you know you gotta start all over again. Her broad nose, angular cheekbones, huge mouth – any of her facial features – could easily be laid claim to by a number of ethnic groups. Her temper could only be derived from the most fiery.

Jeez, do her and Jimmy fight. I’ve known him to come rushing out of there at night, not giving a damn about who or what might be outside, only knowing that it was preferable to what was within.

How long they been together, even they couldn’t rightly say. It’s a matter of whether you want to include the times she’s left him or not. Which, I guess, makes them sound pretty fragile, but you know how those things are; sometimes they can go on forever.

*

It went through my head to go over to the Old City in the afternoon and do some scavenging. But, with every chance of the fog rolling back in, I decided to stay in the Village and do some of the chores I’d been putting off; like sewing up that big tear in my old overcoat. I hunted out a needle and thread and went to sit outside in the pale warmth of the winter afternoon. I was one of many out there trying to uncurl their locked old spines and I felt a touch embarrassed by my display of domesticity; a guy like me doing needlework.

I’d only been out there a short while when I heard Jimmy screaming for me. I looked up to see him hopping and stepping wildly in my direction, pushing people out of his way, stumbling along with some crazy chasing after him.

‘Big Guy! Big Guy!’ he cried.

It was pretty obvious what had happened. Jimmy’d been sorting through the dead couple’s lean-to for more stuff and this crazy had decided to join him. The little guy wouldn’t have liked that. He probably got all snippy, tried to shoo the intruder away, to tell him everything was his, and a fight had broken out.

‘Big Guy, help!’

It was a noticeably uneven race. Jimmy hop-stepping it along, his stick flailing in the air, legs going at all angles, whilst his pursuer, a look of concentrated fury on his face, was rapidly gaining on him.

My first instinct was to laugh. I mean, he really does ask for it sometimes. But something about how single-minded the crazy looked and how frightened Jimmy was, made me realise this was a bit more than the usual squabbles we get round here.

‘Big Guy!’ Jimmy wailed, rapidly running out of breath.

With that, his bad leg gave way and he fell over, lurching into the side of someone’s lean-to, almost collapsing it.

The crazy was on him in a moment, straddling him, and it was only then – as he drew it out, as he raised it up – that I realised why Jimmy was so frightened. The guy had an axe; big and heavy, with a blade polished and shiny from being forever sharpened.

I jumped to my feet and started to make my way over, but I knew I wasn’t going to make it. I shouted as the axe momentarily hung there, like a bird of prey about to dive, then the guy brought it down as hard as he could onto Jimmy’s naked head.

Only thing was, it never made it. There was a sound something like the snap of short-circuiting electricity, and the next thing I knew the crazy was flat on his face, his body twitching like he was having a fit.

I tell you, I seen it before, but never up that close. It’s so sudden. So absolute. One moment the guy had been about to take Jimmy out, the next he’d been taken out himself.

‘Jesus!’ Jimmy whined, struggling free of the convulsing body. ‘What the hell happened?’

‘Satellite,’ I growled, with a calm I certainly didn’t feel.

Jimmy tried to scramble to his feet, his good leg no more steady than his bad. ‘Is he alive?’

‘Yeah. Must’ve seen it as Violent Assault. Or Bearing a Weapon.’

For several moments we stood there looking at the crazy twitching on the ground, his eyes gaping like they were ready to burst out of their sockets, a string of drool sliding from his mouth.

A crowd began to gather, moving tentatively in, as if they were ready to turn and flee at any moment. I mean, it’s really something – our new God, this judgement from On High – and to see it up close like that left you feeling like you’d just witnessed some terrible miracle.

*

I don’t rightly know how to explain to you about satellite policing. I guess its roots lie in the early part of this century, when so. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...