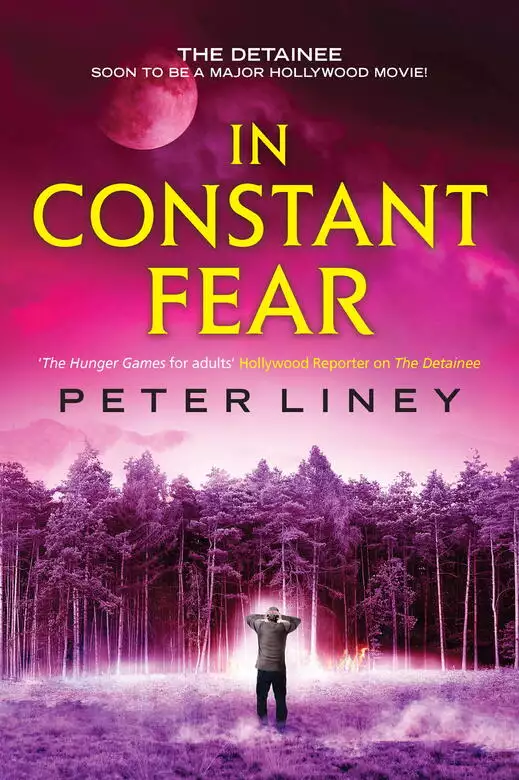

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Over a year has passed since "Big Guy" Clancy and the ragged band of survivors managed to escape from the hellish reality of the City. Pursued by the ruthless leader of Infinity-the corporation behind the systematic extermination of thousands of "lower class" citizens-they've been on the run ever since, constantly looking over their shoulders. Despite this, they have forged a new life working the land on an abandoned smallholding on the other side of the mountains. Hidden there, they are as close to happy as they can be. But peace is short-lived. Strange things start to happen in the valley: too many unlucky coincidences convince them that another power is rising against them, and there are many questions to be answered: what is the shadow maker? And who-or what-has begun to howl in the night?

Release date: December 22, 2015

Publisher: Jo Fletcher Books

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

In Constant Fear

Peter Liney

I didn’t know what it was. Really, I had no idea. It wasn’t a howl and it wasn’t a scream, it was something in between, but whatever was making it – and I guess it was some kinda animal – it sure was in a bad way. For a moment I just stood there, every fibre of my body locked, my breath hanging out in mid-air, hugging my precious little bundle that bit closer to me.

I’d heard it first a few days earlier – around about the same time, in the early hours – just the one animal, and much further away, over towards the mountain, but now there were two or more, and a whole lot closer, maybe only on the far side of the woods.

God, but that was one helluva disturbing sound. Worse than torture, that made you think that, like it or not, you were part of it – it couldn’t just be dismissed as particular to another species. It was a universal pain, and I’d bet there wasn’t one living creature in the valley that wasn’t holding its breath or feeling sick to the stomach the same way I was.

It did go through my head to go over there, or at least get that bit closer – maybe someone had set traps or something? A herd of deer had wandered in, steel jaws snapping shut all around, and now they howled and screamed as they tried to wrench their limbs free, ready to tear their bodies apart in their blind urge for freedom? But I didn’t dare risk it, not with who I had with me.

A pizza moon with an extra large bite out of it continued its slow descent towards the mountaintops, ghostlike and abandoned, the occasional dark cloud passing before it, creating monochrome and murk. I waited ’til the howling had died down, ’til whatever it was fell exhausted – maybe even dead? – then resumed my slow pacing of the farmyard, knowing I’d soon be in a whole lotta trouble if I didn’t.

It was over a year since we’d escaped from the City: a year of relentlessly being pursued, always having to move on, looking over our shoulders even in our sleep – and you wanna know something? – the best year of my life.

I guess that’s one of the things about life: we might think we do, but the truth is, we got no idea what’s waiting for us – no matter how much we might plan or how far we think we can see ahead. That’s just a projection, a possibility, us trying to make order out of chaos. We got no idea what might be waiting for us around the next bend – in fact, I hate to tell ya this, but we might not even make it round that next bend. Take me, for example: if you’d told me a couple of years back when I was imprisoned on that stinking, merciless Island how my life would change, where I’d be now, I probably would’ve laughed in your face. In fact, I was such a bad-tempered sonofabitch, I might’ve laid you out cold for trying to make fun of me. But here I am, at an age where a lot of folk might think it’s time to start taking things easy, and guess what? . . . I’m a father.

It’s true! From this wrinkled old body has sprung the most unbelievably tender of new life.

I have a son. His name is Thomas, and I love him every bit as much as I love his mother, but in a different way, which was why I was walking him around the yard at three in the morning, ’cuz although he wanted to inform everyone he was exactly seven months old that very day, I had a fair idea no one else was interested.

I owed it all to Lena, of course. She’d given me back my life – in fact, she’d returned it to me a thousand times better than it ever was before. All those years of being one of society’s unwanted, no longer the ‘Big Guy’ but just a ragged, bitter old hulk scratching out the most pathetic of existences on that Island . . . I’d given up. Then she came along: this remarkable blind young woman hiding in the old subway tunnels, and with her came hope, a reason not just to go on but to fight against the vicious scum who ran that place – if you can call terrorising the old and abusing the young ‘running’ a place – ’til finally, with the aid of our own little techno genius, Jimmy, and one or two other equally unlikely allies, we managed to destroy that hell that held us and escape to a better life.

The only problem with that was, it wasn’t better, it was a whole lot worse. When we finally left the Island and got ashore, the night of the big exodus, the City was burning from one end to the other. The streets were a battlefield: rioting, looting, people killing each other for no good reason. What was more, the fires spread and with the whole city ringed by flame, there was no way out. We had to find somewhere to hide, somewhere safe not only from fires and mobs but also from Infinity; those in control, who made the Wastelords look like nothing scarier than kids who pulled the wings off butterflies. And at their head – a whole new development of the human species, and one who, though female, I’d freely admit, frightened me more than anyone else had in my life.

If you’ll forgive the presumption of a guy who took sixty-four years to become a father, a little tip for those of you planning on having a kid: it’s a real convenience if one of you’s an insomniac. I’ve always had periods when I couldn’t sleep – a couple of months on, a couple of months off, just one of those things, I guess. It can drive you crazy – I mean, literally, you get some pretty dark characters come calling for you in the middle of the night. But now I had someone to keep me company: this little bundle I was always carrying around with me. Mind you, his choice of conversation wasn’t exactly wide-ranging, being pretty well limited to what went in and what came out. To be fair, when he wasn’t hollering, he made a damn fine listener; just lying there, staring up at me with those drunken blue eyes as if he was in shock that someone like me could be his father.

Can I say that again? I’ve always hated those people who go on and on about kids and parenthood like it’s the greatest thing ever, but you know, I am the boy’s father, and dumb old big guy or not, I did help make him . . . not that you need to be that intelligent to produce children, as you may have noticed.

We never actually discussed it, but gradually Lena and me fell into this routine where she mostly took care of him in the day and I did what I could at night: answering that shrill call, assessing his needs and passing him over if all else failed so that greedy little mouth of his could start snuffling out mother’s milk on draught. The only problem with that was, it didn’t take him long to work out that I was always there, at his beck and call right throughout the night, and he really played on it.

Like that night: I knew there was nothing wrong with him – he’d been changed, fed, winded, whatever and just wanted a bit of company. Still, it had given me the excuse to take him outside, to pretend I didn’t wanna disturb the others, when actually, I was feeling that bit disturbed myself.

We’d been squatting on the farm for five months or so by then, and apart from the occasional unwanted visitor, the many crazies roaming around, we’d slowly begun to relax, to pray that maybe Infinity had given up on finding us. To be honest, it was more of a smallholding than a farm. There were any number of them abandoned out there: family concerns whose proud owners would rather walk away than sell up to the creeping conglomerates.

The irony of those smallholdings was that they’d had people busily working on them, while the giant spreads where the big boys’d got their own way and everything was flattened up to the horizon, were computer-operated, ‘ghost farms’, watched over by satellites and with everything done by machine: planting, watering, harvesting – so all the company had to do was to come out and pick up the packed crates.

’course, everything got messed up when some of the commercial and communication satellites were brought down with the punishment ones. They tried bringing workers out here, reverting to good old-fashioned people-power, but the fires, the remoteness, no way to enforce protection – or discipline – thanks to the absence of punishment satellites, meant there weren’t too many prepared to give it a go.

Our place had belonged to a family, that was clear ’cuz of the stuff left behind – not just bats and balls and bikes, things like that, but pencil marks on the kitchen wall showing how the kids were growing – and for some reason it made me feel that bit more warmly disposed towards it.

Mind you, the first time we laid eyes on the place, it looked pretty sorry for itself: two small fields, once laid to wheat, all dried up and flattened like a pair of straw tablemats, vegetables rotting in the ground or run to seed, worm-riddled fruit fermenting under the trees. We salvaged every last ounce we could, and were grateful for it, but it was clear that if we were gonna stay there, we had to plant more.

Without any kind of vehicle or livestock, we had no choice but to restore the old plough Jimmy’d found in the lean-to at the back of the barn and drag it across the fields by hand. We took it in turns, working in teams of four, me trying to insist on doing more than my share and keeping going ’til my old legs felt like a couple of condemned tower blocks.

What really did surprise me was how much the kids took to it out there – it was as if they were growing along with everything else. Gordie was starting to look like a proper young man, and actually, with the sun on him, plenty of exercise, his hair that bit longer, not a bad-looking one at that. Gigi didn’t change that much, just grew a bit taller, a bit more substantial – she let her old clothes out rather than come up with anything new, maybe so she could keep her ‘style’, that odd, multi-layered look; she even kept the same seagull feathers in her hair. But Hanna – well, she was the one who really blossomed. She’d completely lost that slightly startled look she used to have about her, as if every oncoming moment of her life was a potential threat, and with all that tall measured grace and tumbling dark hair, I tell ya, was becoming quite a beauty. She gained in confidence, no longer keeping her ballet just for when she was alone but dancing all over, especially out in the fields – she didn’t care if you stood and watched her or not.

As for the more senior members of the gang, well, our new situation had done Jimmy and Delilah a power of good: they were more content, more in harmony, than I ever could’ve imagined back when I first met them on the Island. Not only were they finally free, they weren’t tripping over each other any more either. The little guy spent most of his time out in the barn (or should I say, ‘his workshop’), playing around with an impressive stockpile of assorted technology, powered by the old solar panel tree he cleaned up and restored; while Lile sat out on the porch, quietly smiling to herself and counting and then recounting all her belated blessings.

As for Lena and me, well, I guess I don’t have to tell you how well things’d worked out for us. I’d thought we were happy before, but now, with Thomas, I knew I’d got more – way more – than anyone had a right to. It’s true we had our problems when we first left the City. That day we escaped and stood there looking down from the hills and she told me she’d gone blind again – I can’t tell you how bad I felt. I wanted to turn around then and there and go right back, find Doctor Evan Simon and get him to operate on her again, but with Infinity chasing after us – well, it wasn’t exactly an option. Over and over I told her that as soon as it was safe we’d go back and get them fixed, until eventually she started getting that bit impatient with me, going all silent or changing the subject, and I realised it was best to shut up, though that didn’t mean I wasn’t still thinking about it.

When we first settled on the farm I came up with all sorts of ideas to make her life easier: some worked out, others didn’t. I found these rolls of wire in the barn and used them to map out the surrounding area. I hammered in posts and hung lines with identifying markers on each one, so the wire leading to the woods had twigs attached; the one to the barn had steel washers, and to the road, small rocks – and so on. I mean, she would’ve mapped everything out in her head soon enough – she’s always had this unnatural gift for it – but I wanted to give her a head start. ’course, she didn’t need them for long, but I left them there just in case.

But great as it was not just to have our own place but to be out in the country, smelling fresh air for the first time in more years than I could recall, it was having Thomas that really transformed us from being a couple to a family, and that’s a helluva leap, believe me.

Almost as if I couldn’t go another second without seeing him, without having proof of his existence, I paused in my slow, jigging circuit of the farmyard and looked down into the folds of the little guy’s favourite blanket – the blue and white checked one that, even at his age, he was reluctant to be parted from. I was greeted by that same dazed expression that hinted at a terrible mistake: surely his father should’ve been the next guy in line, or the one after that? The banker or the businessman, the one with all the money and comfort in the world, not this wheezy old big guy squatting on someone else’s abandoned property?

It’s kinda odd to build your life around something that barely fits into the palm of your hand – well, my hand anyway. Though I guess that’s why you do it: ’cuz he or she is so vulnerable they need your constant protection. Sometimes it’d frighten the hell outta me that in this insane and brutal world we’d voluntarily created our own weakness, an Achilles heel which could so easily destroy us, then again, we wouldn’t’ve had it any other way.

I was about to return into the house and try to settle him back down when that terrible howling started up again, and much closer this time, almost sounding like it was on this side of the woods – like whatever it was had been silently stealing over in my direction.

What the hell? It wasn’t like anything I’d ever heard before. Not so much threatening in itself, but more like I could feel their pain, how terrified they were.

I stood there for a moment, debating whether to take Thomas inside and grab a torch, when I heard the door of the farmhouse close behind me.

‘Clancy?’ Lena whispered into the darkness.

‘Yeah,’ I answered, and in a moment she’d honed in on my voice and was at my side, her expression almost as pained as the howling. ‘What is that?’

‘I dunno,’ I replied.

‘Sounds like something’s being tortured,’ she said, instinctively taking Thomas from me, I guess also feeling that urge to protect.

‘Hey. What do we know?’ I replied, trying not to sound that concerned. ‘City folk. Could be anything. An owl maybe.’

‘We’ve been out in the country for a year now and I’ve never heard anything like that,’ she pointed out, ‘and I don’t think you have either.’

I sighed to myself, all those dark thoughts churning away inside me again, that in some way this might be connected with Infinity.

‘You sure it’s an animal?’ Lena asked.

‘I’m not sure of anything.’

We stood there listening for a few moments as the noise thankfully started to subside again. ‘Come to bed,’ she said, as if she’d made a decision, and turned towards the house, Thomas firmly clutched in her arms.

‘Gimme a moment.’

‘Clancy.’

‘Okay, I’m coming.’

Still more concerned than I was letting on, I slowly followed after her. The fly-screen clicked shut just as I reached it and I was about to swing it back open, to follow Lena inside, when – Jeez, I don’t how to describe it – the weirdest thing happened: something passed me by. Something was there – and then it wasn’t. There was a disturbance, like a ripple throughout the night, and then it was gone.

I turned back to the step, looking all around me, the hairs on the back of my neck twanging away like they had electricity passing through them.

What the hell was that? There was nothing in the sky, I couldn’t see anything moving across the land, but something had been there, all right. Even the howling had stopped abruptly, as if whatever it was had been sufficiently unnerved to forget their distress.

I stayed there for several minutes, squinting hard into the darkness, checking all around, those hairs on the back of my neck springing up again every time I recalled how I’d felt, but nothing else happened.

Finally I followed Lena in, locking and bolting the door, then taking one last look outta the window. There was still nothing to see, but I had this strong sense that a shadow had somehow stretched its way over the mountains, across the valley and the road and now was travelling up the slope towards us.

CHAPTER TWO

Those first couple of days out of the City, skimming along country roads in the limo we took from Doctor Simon, were really something. At first I described everything to Lena – the mountains, the forest, a beautiful view – trying to make sure she didn’t miss a thing, but again she got all impatient with me, telling me to pipe down and complaining that I was spoiling the moment. I guess the thing was, she could feel the freedom every bit as much as anyone else, and as far as she was concerned, that was all that mattered.

It took me a while to see it her way, to appreciate I’d been creating a bit of tension; when I finally did, the mood in the limo noticeably lifted: four adults and three kids blasting off to Planet Delirium. We sang endlessly, laughed long and hard for no particular reason, and for ever hung outta the windows calling out to every animal, tree and rock we passed. Okay, so there was still the occasional fire that meant a lengthy detour, and any number of times we crested the top of a hill to be met by nothing but a blackened wasteland, but we knew it would grow back again – and so would we.

Jimmy had reprogrammed the limo, taken out most of the security features – locator, return-to-owner, voice recognition – so we could go wherever we wanted (and more importantly, I suspect, so he could add to his growing collection of scavenged technology). The only problem was, once we got off the main road and left the power strip, the limo switched to auxiliary – good old-fashioned gas – and we had to be real careful about every mile we covered.

I can’t tell you how many close shaves we had during those first couple of months, the number of times we almost got caught. Infinity Dragonflies were coming and going day and night, swinging from one side of the sky to the other, stopping dead and hovering over one particular spot; that thunderous thrumming pulsating across the forest floor, their spotlights arrowing down like they were borne on silver stilts. Some days there were so many we had to stay put, camouflaging the limo with branches and hiding amongst the trees. They even brought in armoured pursuit vehicles, each one carrying half a dozen or so Specials, roaring around all over the place, smashing up everything in their way. A couple of times they were upon us almost before we knew and all we could do was make a run for it, desperate to draw them away from the hidden limo, going deeper and darker into the forest, like parent birds distracting predators from the nest, slipping back only after we were sure they’d gone.

It got to the point where we were utterly exhausted, starved of sleep and food, and though no one was saying it, there was this growing sense that it could only be a matter of time. But Jimmy – God bless that little guy – worked out that we had to be close to the limit of a Dragonfly’s range; if we travelled on another twenty or thirty miles, maybe up into the mountains, we’d be out of their reach.

That night we all piled into the limo and slowly worked our way out of the forest and onto the deserted country road. ’course I couldn’t use the headlights and it wasn’t long before I was reminded that my old eyesight ain’t what it used to be by going off the road, not once, but twice, putting more dents into the Doc’s precious vehicle, a lotta swearing and cussing going into getting us out of the ditch and back onto the road.

I got us as far as I could, to the foothills that led up to the mountains, but was forced to stop the moment I saw the dawn starting to clamber up over the horizon. We returned the limo to the forest, again disguising it with branches, everyone splitting up to explore the immediate area.

It was the kids who found the cave – hidden away behind this big slab of upended rock, like it was the front door or something. Gordie, competitive as ever, claimed it was him, but Gigi got so annoyed that in the end he had to acknowledge it might’ve been more her. They called us over, jumping up and down and getting all excited, like they’d found an abandoned castle or something. Mind you, it was quite a find, especially how roomy it was. A little damp, which proved a bit of a problem, but we still ended up living there for the best part of six months. And, of course, it was where Thomas was born.

Thank God, Delilah took over that afternoon, what with me rushing around like a wild-eyed headless chicken. I didn’t have a clue what to do and couldn’t have been more panicked if Lena’d had half a dozen bullets inside her. Lile sent the kids off for a walk before ordering Jimmy to get lost too – telling him outright it wasn’t seemly for him to be that close to a woman in her condition. All I can remember is her screaming at Lena to push, ignore the pain it rewards you with and ‘Push! Push! Push!’ for all she was worth.

If you’ve never seen it, when that baby starts to come out, and no matter how natural you tell yourself childbirth is, it is one helluva shock – as if you can’t believe that’s where it’s been hiding all that time. I cut the cord myself, with the hunting knife I’d spent for ever sharpening and sterilising (the same one I once used to scar my side that time, to make out I’d had a kidney transplant so I’d be taken into the fortress of the Infinity building to have it removed).

Afterwards, Lena just lay there, cuddling little Thomas and looking so proud of herself. She kept gently feeling him all over, working out what he looked like, and if she was frustrated at not being able to see him, if she was feeling the weight of her disability, she sure didn’t mention it.

For a while everything seemed to work out just fine. ’course, it was a helluvan adjustment having another person around, especially such a demanding one, and maybe it was my age – I was beginning to feel every one of those sixty-four years – but he really tired me out. Yet gradually, I guess as all new parents do, we got used to him. Then one day the little guy developed a cough, his tiny lungs started to clog and we knew we had to move on, that the cave was too damp for such a new life.

Jimmy suggested we go over the mountains, that not only would we be safer from Infinity, but the lie of the land would mean there’d be far less hydrazine residue left over from the punishment satellites. The only problem with that was there wasn’t a direct route: if we’d taken the limo, we would’ve had to have headed down to the pass and gone around that way, but it would’ve meant the best part of a day and just about all of our gas.

In the end, it was Hanna who came up with the answer: why not just hide the limo in the cave and make our way over the mountain on foot?

That poor vehicle took a real battering on its way up the slope and into the cave. The slab just outside the entrance meant I had to keep going back and forth, back and forth, ’til eventually I managed to manoeuvre it into place. And as for the mountain, once we started to climb – it might not’ve been that steep or high, but it was still one helluva challenge for someone like Lile and that old sawing single lung of hers. Not that I reckoned any of us felt we had a choice: not where the baby’s health was involved.

There were times when I wondered if Thomas was the real reason why Lena didn’t wanna talk about her blindness any more. Perhaps some animal instinct had kicked in and shifted all her priorities from her to him. She was always aware of the little guy, no matter what the situation, where he was and what he was doing – as if my knife hadn’t cut that cord at all, and never could do.

It took a while of waiting for what I hoped was the right moment, but in the end I told her what Doc Simon had said: about her being the only woman he was aware of who was able to bear a child, that those four years of living underground in the tunnels had meant she’d avoided the effects of the hydrazine poisoning that’d been spilling out of punishment satellites – or ’til Jimmy went and brought them all down.

I thought she’d be really shocked, that she wouldn’t know how to deal with it, but she just dismissed it as another of the Doc’s games – which I guess made a kinda sense. As far as she was concerned, Thomas was our little miracle and that was an end to it. It would’ve worried the hell out of her to have to entertain the idea of him being other people’s miracle too; that we might have some kinda moral responsibility to share the little guy.

Anyway, in terms of our survival, of Infinity’s pursuit, I don’t reckon it made a whole heap of difference. They had more than enough reasons for hunting us down: like Gigi double-crossing Nora Jagger, and both of us briefly thinking that we’d put an end to her miserable life.

I tell ya, I’ve come across some pretty vile examples of humanity in my time. Some of the scum Mr Meltoni used to send me to deal with – well, let’s be honest, some of the scum he had working for him – were so randomly vicious and violent, so beyond redemption, you felt like you wanted to burn out what they had in their heads, set them to default, and hope you ended up with something better. But Nora Jagger? . . . Jesus, she’s something else. She’s got no arms and legs, just these specially-made prosthetics – or to be more accurate, weapons – she attaches to herself. They’re stronger, more powerful than you could ever imagine, and utterly lethal at her bidding.

I’d seen enough of her to know she’d never give up searching for us, no matter what the reason; that she probably spent hours each and every day dreaming up new ways to torture and kill us and wouldn’t stop ’til she’d used each and every one. If that was the reason why those animals were screaming into the night, ’cuz they could sense her on her way, for sure, I didn’t blame them – in fact, if that did turn out to be the case, I’d start screaming too.

*

The following morning, Jimmy, Gigi and me headed up over the hill towards the next valley. It said a lot that I often left Gordie behind now, trusting him to look after Lena and the baby in case any crazies came a-calling. And if he stayed, generally that meant that Hanna did too, and Gigi would immediately make a point of volunteering to go along, so who stayed and who went pretty well resolved itself.

Our smallholding was kinda on the edge of things. You only had to get over the hill and there were half a dozen other groups and families who’d done the same as us: taken over abandoned spreads, done any necessary repairs, dismantled any automatic machinery that could be used by hand. Several of them had even got livestock: not much, maybe a dozen or so cows and a bull, a horse to help out with the ploughing (though, apparently it had a mule-like habit of occasionally refusing), a couple of goats – some had been rounded up but most just wandered in of their own accord, like they’d given independence a shot but hadn’t much cared for it.

We would’ve preferred to have lived over there, too – strength in numbers, after all – but by the time we’d arrived there was nowhere left. Mind you, they did tell us about our place – how it’d been left empty, that no one had moved in ’cuz it was out on its own and considered too vulnerable.

I don’t know how many people were living in that valley, maybe thirty or so, and all sorts, young and old. No kids, I noticed, and no babies – I mean, it could’ve been just coincidence, but I wouldn’t have wanted to bet on it.

We were going to see this guy, Nick, in his fifties, short but heavy, of Greek extraction. He didn’t exactly care for the title, but most of those over there saw him as the village elder, mainly ’cuz him and his grown-up family were the first there. Jimmy’d done this trade with him – his wheat seed for a signal-booster – and it was time to make the exchange. There’s not a lotta communication gets over that side of the mountains, not since Jimmy prompted the punishment satellites to have their little shoot-out in the sky. There were one or two places where you might get a signal, but you’d better be prepared to climb way up, and even then, it’s weak or intermittent at best. I didn’t know whether Jimmy’s booster would make any difference, but I guessed Nick thought it was worth playing around with.

For our part, we were really hoping that if we could plant some wheat, get a good harvest, we could start grinding flour, for bread, pies, cakes, whatever. Nick’d cautioned us that it was getting a little late for summer wheat, but as long as the weather was kin

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...