1

APRIL

DECEMBER 29, 8:15 P.M.

I’m one breath away from losing a zipper. It wouldn’t even have to be a deep one—just a normal-sized breath, which I can barely manage in this glorified torture device of a ball gown. With every inhale, the boning cuts into my skin like teeth, reminding me of two universal truths. One: debutantes aren’t supposed to indulge, including in oxygen. And two: I’m pretty sure these dresses are designed to keep us from running away.

“Uh.” Milford, my appointed escort, looks up from the phone he snuck into his suit pocket. “Are you gonna be sick or something?”

Heat rushes to my face as I realize I’m death-gripping my magnolia bouquet. Milford doesn’t look especially worried, only disturbed, but my face gets hotter as I start to worry that he thinks I’m blushing because I have a crush on him. I don’t—but does worrying about this anyway make me a narcissist or just socially anxious? Or both? Suddenly I’m layers deep in a nesting doll of anxiety, worrying about my worrying, and all I can do is force out “I’m fine.”

I am decidedly not fine, but Milford goes back to his phone, thank god. I go back to breathing: in for four, hold for seven, out for eight. It’s not easy, since my lungs are, you know, being squeezed to death by a custom-made prison.

I wince, thinking again of how much this dress must have cost Dad: a clean thousand that could have gone toward my college fund or literally anything else. If Dad just wanted to burn dollars, I would have happily used them for photo paper or film, since I’ve been blowing through Beaumont’s darkroom supply. But according to Dad, it’s “expected”—his favorite word when it comes to all of this debutante stuff. Every Maid here has a custom dress. I just so happen to be the only one with the figure of a wooden plank, hence the extreme measures taken to keep my strapless dress from becoming a belt. Like an unfriendly reminder, my skin starts to itch under the beaded top.

“I think we’re next,” I mumble. I think, as if we’re not the only couple left in the hallway. The qualifiers always slip out before I can stop them, a knee-jerk apology for speaking.

Milford looks at the door to the ballroom, then sighs, slipping his phone back into his pocket and holding his gloved arm out for me. I take it, cringing at the forced formality. Apparently, we debutantes are also incapable of walking without a strong teenage boy to support us. Sorry, a strong teenage Duke, because that’s their official title. One way New Orleans debutante nonsense is different from regular debutante nonsense is that celebrating how rich and important we are isn’t enough. We have to literally be royalty. Maids, Dukes, Queens. It’s a Mardi Gras thing.

Also, one could say, an asshole thing.

My own personal Duke, Milford Wilcox III, was assigned to me by either the debutante gods or the alphabetical order of our last names, whichever came first. He’s also a senior at Beaumont, but all I really know about him is that 1) he lives in a multimillion-dollar mansion, 2) his dad is running for mayor, and 3) he’s probably not psyched to be escorting the most socially awkward Maid to ever disgrace this country club.

From the other side of the door, the jazz band’s muted rendition of “Someone to Watch Over Me” beats like a death march. I picture Dad’s beaming face in the audience and think of the mantra I’ve been repeating all night: This means a lot to my dad. My dad means a lot to me. Sure, debutante balls are historically racist, sexist, classist, and basically everything wrong with New Orleans and this country, but I can set aside my morals for one night. Right?

Wrong, says a louder voice in my head. Because now, in my too-tight dress and my too-big gloves, all I can think is that last year, Margot stood in this very ballroom less than a day before they found her body.

It rushes up in my throat: a plea, a panic, anything that will get me out of this. But it’s too late. Inside the ballroom, the applause for the last Maid fades, and Mrs. Johnson’s voice comes over the microphone like God, if He were an aging Southern belle.

“Presenting Maid April Whitman!”

I know I’m the one who was worried about missing our entrance, but now my shoes feel glued to the floor. But it’s officially too late to run. Milford has to tug me out of the hallway and under the hot lights of the stage.

The country-club ballroom yawns in front of us, high ceilings dripping with chandeliers that look suddenly precarious, like they could come crashing down at any moment. There’s a pitiful smattering of applause as we step onto the old wooden floor, white gloves against champagne flutes. I don’t blame them for feeling lackluster. I’m the last Maid, and it’s pretty hard to stay enthusiastic after watching nine other girls get paraded around like Wagyu cattle.

We round the stage, and the lights are blinding, turning the audience into shadowy shapes in folding chairs. I can still spot Dad, though. He gives an actual standing ovation as we pass, clapping with his hands up high, like this is one of his favorite operas and I’m the prima donna who just gave a career-defining performance. Next to him, Mom gives her best I know you hate this and I’m sorry smile, and I feel a bubble of warmth. We’re doing this for Dad. I can do this for Dad.

As we near the center of the ballroom floor, my shoulders itch for the familiar weight of my Nikon strap. Instead, I catch a glimpse of another camera: the official event photographer, setting his aim. Sweat prickles in my armpits, heat rushing to my face. It’s a special kind of panic, being the one on the other side of the lens. Being seen.

Milford clears his throat next to me, and I remember that I’m supposed to curtsy. Mrs. Johnson’s words from this morning’s rehearsal echo in my head: Brighter smile, April. It’s a ball, sweet pea, not a funeral.

Sure, I wanted to tell her. Until I die of oxygen deprivation.

Now I dip down just like I did this morning, doing my best approximation of happiness while my pulse beats in my ears.

Flash.

And then it’s over. Milford drops me off with the rest of the Maids, who ring the empty throne in the middle of the floor, before lumbering over to the makeshift backstage area. I breathe out shakily.

“Don’t lock your knees,” a voice next to me whispers, causing the tension to immediately reflood my body.

Vivian Atkins, one of the other two Maids in my class at Beaumont. At school, Vivian’s usually in jeans and a T-shirt or her soccer uniform, but somehow, she’s just as intimidating in a ball gown, her strawberry-blond hair cascading in a classy ponytail that she could probably use to strangle me. Maybe I’m projecting. While I disagree with popularity as a concept, Vivian is part of that crowd, and I don’t trust any of them. She’s also never spoken to me before.

I try to form a response, but my voice feels locked inside my throat, so all I manage is a barely audible “Thanks.”

Vivian shrugs, eyeing Mrs. Johnson. “She’ll go feral if a Maid passes out before Lily comes in.”

As if to confirm, Mrs. Johnson shoots us both a smile that says I will quite literally explode if y’all don’t stop whispering during my debutante ball. I guess I don’t blame Mrs. Johnson for being so intense: this whole thing is like her Super Bowl, especially this year. Across the row of debutantes, Piper Johnson—the other Beaumont Maid—is an echo of her mother, looking like the child bride at a Kennedy wedding in her modest cap-sleeve gown, brown hair pinned up in a stuffy sixties updo.

To be fair, we all look like child brides in our white dresses. Which is sort of on purpose, I think. Historically, debutante balls were a way for the elites to announce to society that their daughters were ready to be married off before they hit the ripe old age of twenty-two. Here in New Orleans, this particular brand of hell goes all the way back to the 1850s, when a bunch of rich white supremacists got together to form one of the first Mardi Gras social clubs, the Krewe of Deus—pronounced “crew,” and yes, all of the clubs spell it that way, because of course they do. As a secret society, Deus organized an extravagant, rowdy parade on Mardi Gras Day, followed by a superexclusive debutante ball at night—a lavish masquerade for only the richest and whitest in town.

Somewhere along the way, Deus spawned Les Masques, a debutante ball specifically for high-school girls, which is how I came to be standing here, craving the sweet release of the apocalypse.

Now, even though Mardi Gras clubs like Deus are technically open to anyone—as long as you’ve got money to pay the dues and another member to vouch for your worthiness—I still can’t get past the rotten, gnarled roots of it. And looking around at the other Maids onstage, this ball doesn’t look any less rich or white than they all did a century ago.

My chest tightens again, but I force myself to stay calm. It’s too late now to panic, anyway, because it’s almost the grand finale. The band’s song ends, leaving a hush of anticipation before they start up a drumroll.

“Presenting Her Royal Highness…” Mrs. Johnson pauses, relishing in the ceremony of it. “Queen Lily LeBlanc!”

A trumpet plays royal fanfare as the spotlight swings to the ballroom entrance—the main one, the grand one. The Maids came out of the side door, but this is an entry fit for royalty. Two “pages”—the lucky ten-year-old boys whose parents forced them into page-boy costumes, complete with blond bowl-cut wigs and feathered hats—pull open the heavy wooden doors. The band starts up a dreamy instrumental cover of “La Vie en Rose,” and every head in the room turns to see her.

Lily LeBlanc glides forward in her white ball gown, and somehow, despite all this, the pageantry, the absurdity, the room holds a collective breath. She’s the picture of everything a Queen should be. Regal spine, sparkling crown balanced perfectly on her white-blond updo, two careful coils falling out to frame her heart-shaped face. Wyatt Johnson, Lily’s boyfriend and Piper’s twin brother, is escorting her, but he might as well be invisible, a golden shadow serving only to complement her glow. Everything about Lily sparkles, from her blue eyes and bright smile to her ridiculous scepter and heavy beaded cape.

But I know what the rest of them don’t: it’s a rhinestone glow, so convincing that you almost think it’s real. Real enough that you don’t know you’ve been fooled until it’s too late.

The trumpet croons, punctuated by jazzy drum hits, as Lily and Wyatt parade to the throne at the center of the stage. He holds her gloved hand in his as she ascends the dais, watching her like he can’t believe he gets the honor of helping her up three whole steps. When she makes it to the top, Lily gives Wyatt an adoring smile, and it’s like a premonition of the wedding they’ll no doubt have before Lily turns twenty-five—old-maid status, by Southern standards—only the weird funhouse version where she towers above him on her throne.

With a bow, Wyatt turns and goes offstage with the other guys, and Lily is alone to rule her kingdom. Just before she sits, she steps forward, eyes up, unafraid of tripping over her cape. Her focus seems soft, but then I realize she’s looking at her parents, sitting front and center. Lily’s mom smiles perfectly, looking every bit the mother of a Queen in purple satin. Her dad is proud, eyes glinting the same steel color as the Krewe of Deus medallion around his neck.

I wonder if they’re thinking what I’m thinking, the terrible thought that just drifted into my head like one of the piano’s glissandos: “La Vie en rose” is the song Margot entered to last year. They’ve used it for every Queen’s entrance since god knows when, but some part of me thought maybe they’d change it. Now it feels cursed.

But if it’s crossed Lily’s mind, she doesn’t show it. She lifts her scepter, and slowly, just like she rehearsed, she moves it over the crowd, one side to the other, like she’s casting a spell. One that seems to be working. Time stops, the room enraptured. Then, in the last few measures of the song, she takes her seat, and the spell breaks. The applause is deafening.

I can’t believe these assholes fell for it.

The clapping fades, and so does the music, as we all wait for the next part of the program. I try to hide my cringe at what I know is coming.

“And now,” Mrs. Johnson announces, “presenting the Les Masques Jesters!”

If this whole thing wasn’t already weird enough, this is the cherry on top of the Southern-bullshit sundae. The Dukes stumble onstage like a nightmare, now disguised as “Jesters” in the literal horror show we’ve normalized as Mardi Gras costumes: sparkly medieval-style outfits, jingly hats, and worst of all, peach-colored masks with painted red lips, obscuring everything but their eyes, which peek through two holes in the plastic.

The band starts up a circus-style number, and the boys launch into their unchoreographed dance—bouncing, thrusting, TikTok dances of varying skill level—while Lily looks on, laughing with a glove over her mouth. It’s a tradition, the guys dancing around for the Queen, and everyone seems to think it’s cute. I, however, would rather eat my own bouquet than watch two more minutes of this.

The band rolls into their big finish, and the boys hit their final pose, a bow to their Queen. I let out a breath. Finally, it’s done. Only a few more minutes and I can leave this stage for good.

And then the lights go out.

There’s a breath of shocked silence before the murmuring starts. I strain through the darkness to look at the Maids next to me, but they’re all confused, too. We didn’t rehearse this. My heart pounds against my dress.

“Everyone, stay calm.” Mrs. Johnson’s voice, swallowed now by the din of the crowd. Her microphone must not be working. Wait, why isn’t it working?

And suddenly, light. Click. A projector shines from somewhere in the back of the darkened ballroom, its glow aimed right at Lily, making her shield her eyes. At first, I can’t tell what it is. Moving images of some kind.

When I realize, my stomach plunges.

Margot. Photos, videos dancing across the throne. Margot at school, smiling, laughing, giving the camera the finger. Margot as Queen, her crown crooked on her dark-blond curls like a messier, realer version of Lily. Her ghost. The videos are all silent, but I can still hear her laugh echoing in my memory. I feel around for something to grab onto, but there’s nothing but the limp flowers in my hands.

Through the panic, I try to be logical. Maybe this is some kind of tribute. They said tonight’s ball was dedicated to Margot, didn’t they? But then I see Lily’s face, the strange look in her eyes. Something like confusion.

Something like fear.

The projection cuts off, shrouding the ballroom and Lily in darkness. For a second, there’s nothing.

And then the room lights up. Bright red glows everywhere— on Lily’s pale face and the deep velvet curtains behind us, aimed from somewhere up high, at me and all the Maids. I back away from the light, nearly tripping over my dress, and then I see it: movement near the throne. An arc of red, splashing against Lily’s dress, her face.

Blood.

For a moment, there’s stillness. Lily brings a gloved hand to her face, too stunned to scream, frozen like a photograph with crimson dripping down her gown.

And then, chaos.

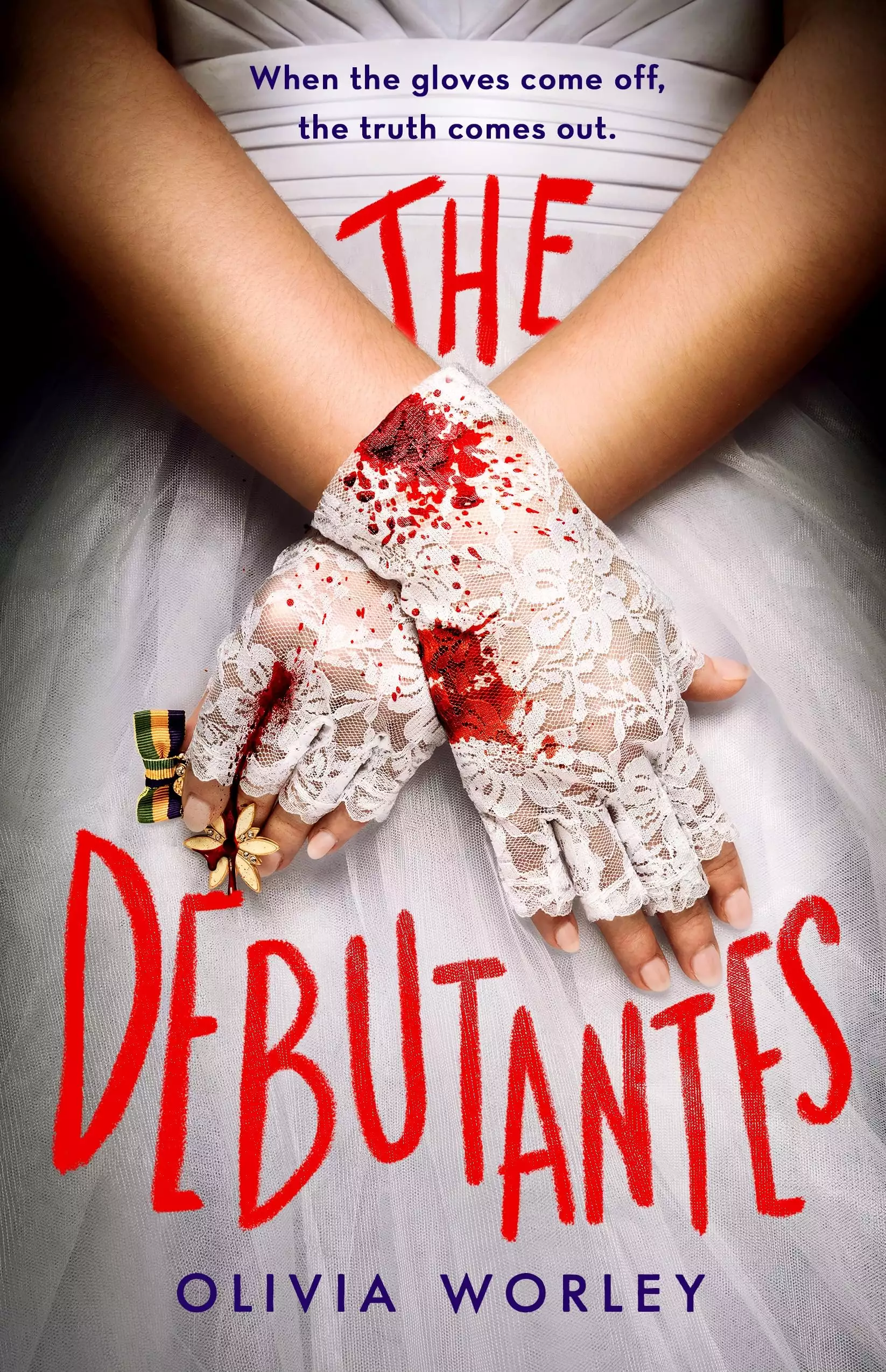

Copyright © 2024 by Olivia Worley

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved