- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

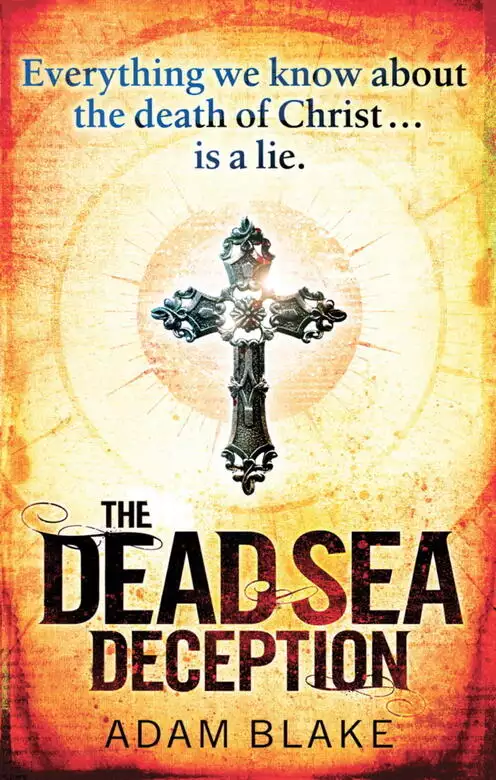

Hidden in the Dead Sea scrolls—the secret of how Christ really died As ex-mercenary Leo Tillman and ambitious cop Heather Kennedy investigate a series of baffling deaths, the trail leads them to the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the deadly gospel hidden within them. But soon Tillman and Kennedy are running for their lives from a band of sinister assassins who weep tears of blood and believe themselves descended from Judas. These "fallen angels" will stop at nothing to expose the world-changing secret of the Scrolls: the secret of how Christ really died. Rocketing from a spectacular plane crash in the American desert to a brutal murder at a London university to a phantom city in Mexico, this is the most gripping, revelatory thriller since The Da Vinci Code.

Release date: May 1, 2014

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Dead Sea Deception

Adam Blake

a spoon into an enormous bowl of ice cream. One of the thoughts that went through his mind as he listened, along with the

first gripes of pity for the dead and bereaved, and dismay at the shit-storm this would bring him, was that this seven-dollar

sundae was now surely going to waste.

‘Emergency landing?’ he asked, making sure he understood. He cupped his hand around the phone to shut out the reverberating

sounds of pins falling and being reset in the adjacent lane.

‘Nope.’ Connie was definitive. ‘No kind of landing at all. That bird just fell out of the sky, hit the ground and blew the

hell up. Don’t know how big it was or where it was coming from. I’ve put calls out to ATC at Phoenix and Los Angeles. I’ll

let you know when they get back to me.’

‘And it’s definitely inside the county limits?’ Gayle asked, clutching at a feeble straw. ‘I thought the flight path was more

to the west, out by Arcona.’

‘It came down right by the highway, Web. Honest to God, I can see the smoke right out the window here. It’s not just in the

limits, it’s so close you could walk to it from the Gateway mall. I already passed the word along to Doc Beattie. Anything else you want me to do?’

Gayle considered. ‘Yeah,’ he said after a moment. ‘Tell Anstruther to get up there and rope it off, a good ways out. Far enough

so we don’t get anyone stopping by to rubberneck or take pictures.’

‘What about Moggs?’ Meaning Eileen Moggs, who comprised the entirety of the full-time staff on the Peason Chronicler. Moggs was a journalist of the old school, in that she drove around and talked to people before she filed copy, and even

took her own photos with an over-sized digital SLR that made Gayle think of a strap-on dildo he’d seen once in a sex toys

catalogue and then tried to forget.

‘Moggs can go through,’ Gayle said. ‘I owe her a favour.’

‘Oh yeah?’ Connie queried, just blandly enough that Gayle couldn’t be sure there was any innuendo there. He shoved the bowl

of ice cream away from him, disconsolate. It was one of those fancy flavours with a long name and an even longer list of ingredients,

leaning heavily on chocolate, marshmallow and caramel in various combinations. Gayle was an addict, but had made peace with

his weakness a long time ago. It beat booze, by a long way. Probably beat heroin and crack cocaine, too, although he’d never

tried either.

‘I’m on my way over,’ he said. ‘Tell Anstruther a good quarter of a mile.’

‘A good quarter of a mile what, chief?’

He waved to the waitress to bring him the check. ‘The incident line, Connie. I want it to be at least five minutes’ walk from

the wreck. There’ll be people coming in from all over when they get a sniff of this, and the less they see, the sooner they’ll

turn around and go home again.’

‘Okay. Five minutes’ walk.’ Gayle could hear Connie scribbling it down. She hated numbers, claimed to be blind to them in the way some people are blind to colours. ‘Is that it?’

‘That’s it for now. Try the airports again. I’ll give you a call when I get out there.’

Gayle took his hat from the empty seat beside him and put it on. The waitress, an attractive dark-featured woman whose name

tag said MADHUKSARA, brought him the cheque for the ice cream and for a hot dog and fries he’d had earlier. She affected to

be scandalised at the fact that he hadn’t touched his dessert. ‘Well, I’d welcome a doggy bag if it was a practical proposition,’

he said, making the best of it. She got the joke, laughed louder and longer than it deserved. He creaked a little as he stood.

Getting old, and getting rheumatic, even in this climate. ‘Ma’am.’ He touched the brim of his hat to her and headed out.

Gayle’s thoughts were on idle as he crossed the baking backlot towards his battered blue Chevrolet Biscayne. He was entitled

to a new car on the police budget whenever he wanted one, but the Biscayne was a local landmark. Wherever he parked it, it

was like a sign saying, THE DOCTOR IS IN.

How was Madhuksara pronounced? Where did she come from, and what had brought her to live in Peason, Arizona? This was Gayle’s town, and he was

attached to it by strong, subterranean bonds, but he couldn’t imagine anyone coming from a great distance to be here. What

would be the draw? The mall? The three-screen movie theatre? The desert?

Of course, he reminded himself, this was the twenty-first century. Madhuksara didn’t have to be an immigrant at all. She could

have been born and raised right here in the south-western corner of the US of A. She certainly hadn’t had any trace of a foreign

accent. On the other hand, he hadn’t ever seen her around town before. Gayle wasn’t a racist, which at some points in his

career as a policeman had given him a certain novelty value. He liked variety, in humankind as much as in ice cream. But his instincts were a cop’s instincts and he tended to file

new faces of any colour in a mental pending tray, on the grounds that unknown quantities could always turn out to be trouble.

Highway 68 was clear all the way to the interstate, but long before he got to the crossroads he could see the coal-black column

stretching up into the sky. A pillar of smoke by day, a pillar of fire by night, Gayle thought irrelevantly. His mother had belonged to a Baptist church and quoted scripture the way some people talk about

the weather. Gayle himself hadn’t opened a bible in thirty years, but some of that stuff had stuck with him.

He turned off on to the single-file blacktop that bordered Bassett’s Farm and came up through the fields on a nameless dirt

track where once, a great many years before, he’d had his first kiss that hadn’t come from an elderly female relative.

He was surprised and pleased to find the road roped off with an emphatic strip of black-and-yellow incident tape, a hundred

yards or so before he was close enough to see the sprawl of twisted metal from which the smoke was rising. The tape had been

stretched between two pine fence posts, and Spence, one of his most taciturn and unexcitable deputies, was standing right

there to see that drivers didn’t just bypass the roadblock by taking a short detour into the cornfield.

As Spence untied the tape to let him pass, Gayle wound his window down.

‘Where’s Anstruther?’ he asked.

Spence pointed with a sideways nod. ‘Up there.’

‘Who else?’

‘Lewscynski. Scuff. And Mizz Moggs.’

Gayle nodded and drove on.

Like heroin and cocaine, a major airplane crash was something outside Gayle’s experience. In his imagination, the plane had come down like an arrow and embedded itself in the soil, tail up. The reality was not so neat. He saw a broad ridge of

gouged earth about two hundred yards long, maybe five or six feet high at its outer edge. The plane had broken up as it dug

that furrow, shedding great curved pieces of its fuselage like giant eggshells along the whole, tortured stretch of ground.

What was left of the fuselage was burning up at the far end and – now that Gayle’s window was down, he became aware – filling

the air with a terrible stench of combustion. Whether it was flesh or plastic that smelled like that as it burned he could

not be sure. He was in no hurry to find out.

He parked the Biscayne next to Anstruther’s black-and-white and got out. The wreck was a hundred yards away, but the heat

from the fire laid itself across Gayle’s body like a bar across a door as he walked over to where a small group of people

was standing, on top of the newly ploughed ridge. Anstruther, his senior deputy, was shielding his eyes as he looked out over

the remade country. Joel Scuff, a no-account trooper who at age twenty-seven was already more of a disgrace to the force than

men twice his age had managed, stood beside him, staring in the same direction. Both looked sombre and nonplussed, like people

at a funeral for someone they didn’t know that well, fearful that they might be called on for small talk.

Sitting at their feet, on the rucked-up earth, was Eileen Moggs. Her phallic camera sat impotently in her lap and her head

was bowed. It was hard to be sure from this angle, but her face had the crumpled look of someone who had recently been crying.

Gayle was about to say something to her, but at that point, as he trudged up the rising gradient of the earthworks, his head

crested the ridge and he saw what they were seeing. He stopped dead, involuntarily, his brain too overloaded with that horrible

image to maintain any commerce with his legs.

Bassett’s North 40 was sown with corpses: men and women and children, all strewn across the chewed-up earth, while the clothes

disgorged from their burst suitcases arced and twisted above them in the searing thermals, as though their ghosts were dancing

in fancy dress to celebrate their new-found freedom.

Gayle tried to swear, but his mouth was too dry, suddenly, for the sound to make it out. In the terrible heat, his tears evaporated

right off his cheeks before anyone could see them.

The photo showed a dead man sprawled at the foot of a staircase. It was perfectly framed and pin-sharp, and nobody seemed

to have noticed the most interesting thing about it, but it still didn’t fill Heather Kennedy with anything that resembled

enthusiasm.

She closed the manila folder again and pushed it back across the desk. There wasn’t much else in there to look at anyway.

‘I don’t want this,’ she said.

Facing her across the desk, DCI Summerhill shrugged: a shrug that said into each life a little rain must fall. ‘I don’t have anyone else to give it to, Heather,’ he told her, in the tone of a reasonable man doing what needed to be

done. ‘Slates are full across the department. You’re the one with the most slack.’ He didn’t add, but could have done, you know why the short straw is your straw, and you know what has to happen before that stops.

‘All right,’ Kennedy said. ‘I’m slack. So put me on runaround for Ratner or Denning. Don’t give me a dead-ball misallocation

that’s going to sit open on my docket until five miles south of judgement day.’

Summerhill didn’t even make the effort of looking sympathetic. ‘If it’s not murder,’ he said, ‘close it. Sign off on it. I’ll

back your call, so long as you can make it stick.’

‘How am I meant do that when the evidence is three weeks old?’ Kennedy shot back, acidly. She was going to lose this. Summerhill had already made up his mind. But she wasn’t going

to make it easy for the old bastard. ‘Nobody worked the crime scene. Nobody did anything with the body in situ. All I’ve got

to go on are a few photos taken by a bluebell from the local cop-shop.’

‘Well, that and the autopsy report,’ Summerhill said. ‘The north London lab came back with enough open questions to bring

the case back to life – and possibly to give you a few starting points.’ He pushed the file firmly and irrevocably back to

her.

‘Why was there an autopsy if nobody thought the death was suspicious?’ Kennedy asked, genuinely puzzled. How did this even get to be our problem?

Summerhill closed his eyes, massaged them with finger and thumb. He grimaced wearily. Clearly he just wanted her to take the

file and get the hell out of his morning. ‘The dead man had a sister, and the sister pushed. Now she’s got what she wanted

– an open verdict, implying a world of exciting possibilities. To be blunt, we don’t really have any alternative right now.

We look bad because we signed off on accidental death so quickly and we look bad because we stonewalled on the autopsy on

the first request. So we’ve got to reopen the case and we’ve got to go through the motions until one of two things happens:

we find an actual explanation for this guy’s death or else we hit a wall and we can reasonably say we tried.’

‘Which could take for ever,’ Kennedy pointed out. It was a classic black hole. A case that had had no real spadework done

at the front end meant you had to run yourself ragged for everything thereafter, from forensics to witness statements.

‘Yes. Easily. But look on the bright side, Heather. You’ll also be breaking in a new partner, a willing young DC who’s only

just joined the division and doesn’t know a thing about you. Chris Harper. Straight transfer from St John’s Wood via the academy. Treat him gently, won’t you. They’re used to more civilised

ways over at Newcourt Street.’

Kennedy opened her mouth to speak, closed it again. There was no point. In fact, on one level you had to admire the neatness

and economy of the stitch-up. Someone had screwed up heroically – signed off way too fast and then got bitten on the arse

by the evidence – so now the whole mess was being handed off to the most expendable detective in the division and a poor piece

of cannon fodder drafted in for the occasion from one of the boroughs. No harm, no foul. Or if it turned out there was, nobody

who mattered was going to be booked for it.

With a muttered oath, she headed for the door. Leaning back in his chair, hands clasped behind his head, Summerhill stared

at her retreating back. ‘Bring them back alive, Heather,’ he exhorted her, languidly.

When she got back to her desk, Kennedy found the latest gift from the get-her-out-by-Friday brigade. It was a dead rat in

a stainless steel break-back trap, lying across the papers on her desk. Seven or eight detectives were in the bear pit, sitting

around in elaborately casual groupings, and they were all watching her covertly, eager to see how she’d react. There might

even be money riding on the outcome, judging from the mood of suppressed excitement in the room.

Kennedy had been putting up quietly with lesser provocations, but as she stared down at the limp little corpse, a ruff of

blood crusted at its throat where it had fallen on the trap’s baited spike, she acknowledged instantly what she ninety-per-cent

already knew – that she wasn’t going to make this stop by uncomplainingly carrying her own cross.

So what were the options? She ran through a few until she found one that at least had the advantage of being immediate. She picked the trap up and pulled it open, with some difficulty

because the spring was stiff. The rat fell on to her desk with an audible thud. Then she tossed the trap aside, hearing it

clatter behind her, and picked up the body, not gingerly by the tail but firmly in her fist. It was cold: a lot colder than

ambient. Someone had been keeping it in his fridge, looking forward to this moment. Kennedy glanced around the room.

Josh Combes. It wasn’t that he was the ringleader – the campaign wasn’t as consciously orchestrated as that. But among the

officers who felt a need to make Kennedy’s life uncomfortable, Combes had the loudest mouth and was senior in terms of years

served. So Combes would do as well as anyone, and better than most. Kennedy crossed to his desk and threw the dead rat into

his crotch. Combes started violently, making his chair roll back on its castors. The rat fell to the floor.

‘Jesus!’ he bellowed.

‘You know,’ Kennedy said, into the mildly scandalised silence, ‘big boys don’t ask their mummies to do this stuff for them,

Josh. You should have stayed in uniform until your cods dropped. Harper, you’re with me.’

She wasn’t even sure he was there: she had no idea what he looked like. But as she walked away, she saw out of the corner

of her eye one of the seated men stand and detach himself from the group.

‘Bitch,’ Combes snarled at her back.

Her blood was boiling, but she chuckled, let them all hear it.

Harper drove, through light summer rain that had come from nowhere. Kennedy reviewed the file. That took most of the first

minute.

‘Did you get a chance to look at this?’ she asked him, as they turned into Victoria Street and hit the traffic.

The detective constable did a little rapid blinking, but said nothing for a moment or two. Chris Harper, twenty-eight, of

Camden Ops, St John’s Wood and the SCD’s much-touted Crime Academy: Kennedy had taken a few moments in-between Summerhill’s

office and the bear pit to look him up on the divisional database. There was nothing to see, apart from a citation for bravery

(in relation to a warehouse fire) and a red docket, redacted, for an altercation with a senior officer over a personal matter

that wasn’t specified. Whatever it was, it seemed to have been settled without any grievance procedure being invoked.

Harper was fair-haired and as lean as a wire, with a slight asymmetry in his face that made him look like he was either flinching

or favouring you with an insinuating wink. Kennedy thought she might have run across him once in passing somewhere, a long

way back, but if so, it had been a very fleeting contact, and it hadn’t left behind any strong impression for good or bad.

‘Haven’t read it all,’ Harper admitted at last. ‘I only found out I was assigned to this case about an hour ago. I was going

over the file, but then … well, you turned up and did the dead rat cabaret, and then we hit the road.’ Kennedy shot him a

narrow look, which he affected not to notice. ‘I read the summary sheet,’ he said. ‘Flicked through the initial incident report.

That was all.’

‘All you missed was the autopsy stuff, then,’ Kennedy told him. ‘There was sod all actual policing done at the scene. Anything

stay with you?’

Harper shook his head. ‘Not a lot,’ he admitted. He slowed the car. They’d run into the back end of a queue that seemed to

fill the top half of Parliament Street: roadworks, closing the street down to one lane. No point using the siren, because

there was nowhere people could move out of their way. They rolled along, stop-start, slower than walking pace.

‘Dead man was a teacher,’ Kennedy said. ‘A university professor, actually, at Prince Regent’s College. Stuart Barlow. Age

fifty-seven. Place of work, the college’s history annexe on Fitzroy Street, which is where he died. By falling down a flight

of stairs and breaking his neck.’

‘Right.’ Harper nodded as though it was all coming back to him.

‘Except the autopsy now says he didn’t,’ Kennedy went on. ‘He was lying at the bottom of the staircase, so it seemed like

the logical explanation. It looked like he’d tripped and fallen badly: neck broken, skull impacted by a solid whack to the

left-hand side. He had a briefcase with him. It was lying right next to him, spilled open, so there again, there was a default

assumption. He packed his stuff, headed home for the night, got to the top of the stairs and then tripped. The body was found

just after 9 p.m., maybe an hour after Barlow usually clocked off for the night.’

‘Seems to add up,’ Harper allowed. He was silent for a few moments as the car trickled forward a score or so of yards and

then stopped again. ‘But what? The broken neck wasn’t the cause of death?’

‘No, it was,’ Kennedy said. ‘The problem is, it wasn’t broken in the right way. Damage to the throat muscles was consistent

with torsional stress, not planar.’

‘Torsional. Like it had been twisted?’

‘Exactly. Like it had been twisted. And that takes a little focused effort. It doesn’t tend to happen when you fall downstairs.

Okay, a sharp knock coming at an angle might turn the neck suddenly, but you’d still expect most of the soft tissue trauma

to be linear, the damaged muscle and the external injury lining up to give you the angle of impact.’

She flicked through the sparse, unsatisfying pages until she came to the one that – after the autopsy – was the most troubling.

‘Plus there’s the stalker,’ Harper said, as if reading her thoughts. ‘I saw there was another incident report in there. Dead

man was being followed.’

Kennedy nodded. ‘Very good, Detective Constable. Stalker is maybe overstating the case a little, but you’re right. Barlow

had reported someone trailing him. First of all at an academic conference, then later outside his house. Whoever signed off

on this the first time around either didn’t know that or didn’t think it mattered. The two incident sheets hadn’t been cross-referenced,

so I’d go for the former. But in light of the autopsy results, it makes us look all kinds of stupid.’

‘Which God forbid,’ Harper murmured, blandly.

‘Amen,’ Kennedy intoned.

Silence fell, as it often does after prayers.

Harper broke it. ‘So that stuff with the rat. Is that part of your daily routine?’

‘These days, yeah. It pretty much is. Why? Do you have an allergy?’

Harper thought about that. ‘Not yet,’ he said at last.

Despite its name, the history annexe of Prince Regent’s College was aggressively modern in design: an austere concrete and

glass bunker, tucked into a side street a quarter of a mile from the college’s main site on Gower Street. It was also deserted,

since term had finished a week before. One wall of the foyer was a floorto-ceiling notice board, advertising gigs by bands

Kennedy didn’t know, with dates that had already passed.

The harassed bursar, Ellis, came out to meet them. His face was shiny with sweat, as though he’d come straight from the bureaucratic

equivalent of an aerobic workout, and he seemed to see the visit as a personal attack on the good name of the institution.

‘We were told the investigation was closed,’ he said.

‘I doubt you were ever told that by anyone with the authority to say it, Mr Ellis,’ Harper said, deadpan. The official line

at this point was that the case had never been closed: that had only ever been a misunderstanding.

Kennedy hated to hide behind weasel words, and at this point felt like she owed little loyalty to the department. ‘The autopsy

came back with some unusual findings,’ she added, without looking at Harper. ‘And that’s changed the way we’re looking at

the case. It’s probably best to say nothing about this to anyone else on the faculty, but we’ll need to make some further

investigations.’

‘Can I at least assume that all this will be over before the start of our summer school programme?’ the bursar asked, his

tone stuck halfway between belligerence and quavering dread.

Kennedy wished it with all her heart, but she believed that giving people good news that hadn’t been adequately crash-tested

was setting them up for more misery later. ‘No,’ she said, bluntly. ‘Please don’t assume that.’

Ellis’s face fell.

‘But … the students,’ he said, despite the self-evident lack of any. ‘Things like this do no good at all for recruitment or

for our academic profile.’ It was such a strikingly fatuous thing to say that Kennedy wasn’t sure how to respond. She decided

on silence, unfortunately leaving a void that the bursar seemed to feel obligated to fill. ‘There’s a sort of contamination

by association,’ he said. ‘I’m sure you know what I mean. It happened at Alabama after the shootings in the biology department.

That was a disgruntled teaching assistant, I understand – a freak occurrence, a chance in a million, and no students were

involved at all. But the faculty still reported a drop in applications the next year. It’s as though people think murder is

something you can catch.’

Okay, that was less fatuous, Kennedy thought, but a lot more obnoxious. This man had lost a colleague, in circumstances that

were turning out to be suspicious, and his first thought was how it might affect the college’s bottom line. Ellis was clearly

a selfserving toerag, so he got civility package one: just the basics.

‘We need to see the place where the body was found,’ she told him. ‘Now, please.’

He led them along empty, echoing corridors. The smell in the place reminded Kennedy of old newsprint. As a child she had built

a playhouse in her parents’ garden shed from boxes of newspapers. Her father had collected them for arcane reasons (maybe,

even that far back, his mind was beginning to go). It was that smell, exactly: sad old paper, dead-ended, defeated in its

effort to inform.

They turned a corner and Ellis stopped suddenly. For a moment Kennedy thought he meant to remonstrate with her, but he half-raised his hands in an oddly constrained gesture to indicate their immediate surroundings.

‘This is where it happened,’ he said, with an emphasis on the ‘it’ that was half-gingerly, half-prurient. Kennedy looked around,

recognising the short, narrow hallway and the steep stairs from the photographs.

‘Thank you, Mr Ellis,’ she said. ‘We’ll handle this part on our own. But we’ll need you again in a little while, to let us

into Mr Barlow’s study.’

‘I’ll be at reception,’ Ellis said, and trudged away, the cartoon raincloud over his head all but visible.

Kennedy turned to Harper. ‘Okay,’ she said, ‘let’s walk this through.’ She handed him the file, open and with the photos on

top. Harper nodded, a little warily. He staggered the photos like a poker hand, glancing from them to the stairs and then

back again. Kennedy didn’t push him: he needed to get his eye in and it would take as long as it took. Whether he knew it

or not, she was doing him a favour, letting him put it together in his own mind rather than hitting him with her thoughts

right out of the gate. He was fresh out of the box after all: in theory, she was meant to be training him up, not using him

as a footrest.

‘He was lying here,’ Harper said at last, sketching the scene with his free hand. ‘His head … there, around about the fourth

stair.’

‘Head on the runner of the fourth stair,’ Kennedy cut in. She wasn’t disagreeing, just wrapping it in her own words. She wanted

to see it, to transfer the image in her head to the space in front of her, and she knew from experience that saying it would

help. ‘Where’s the briefcase? By the base of the wall, right? Here?’

‘Here,’ Harper said, indicating a point maybe two yards out from the foot of the stairs. ‘It’s open and on its side. There are a whole lot of papers, too, just strewn around here. Quite

a wide spill, all the way to the far wall. They could have slipped out of the briefcase or out of Barlow’s hands as he fell.’

‘What else? Anything?’

‘His coat.’ Harper pointed again.

Kennedy was momentarily thrown. ‘Not in the photos.’

‘No,’ Harper agreed. ‘But it’s here in the evidence list. They moved it because it was partially occluding the body and they

needed a clear line of sight for the trauma photos. Barlow probably had it over his arm or something. Warm evening. Or maybe

he was putting it on when he tripped. Or, you know, when he was attacked.’

Kennedy thought about this. ‘Does the coat match the rest of his outfit?’ she demanded.

‘What?’ Harper almost laughed, but he saw that Kennedy was serious.

‘Is it the same colour as Barlow’s jacket and trousers?’

Harper flicked through the file for a long time, not finding anything that described or showed the coat. Finally he realised

that it was in one of the photos after all – one that had been taken right at the start of the examination but had somehow

been shuffled to the bottom of the deck. ‘It’s a black raincoat,’ he said. ‘No wonder he wasn’t wearing it. He was probably

sweating just in the jacket.’

Kennedy climbed part of the way up the stairs, scanning them closely. ‘There was blood,’ she called over her shoulder to Harper.

‘Where was the blood, Detective Constable?’

‘Counting from the bottom, ninth and thirteenth stairs up.’

‘Right, right. Stain’s still visible on the wood here, look.’ She circled her hand above one spot, then t

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...