- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Madame Katerina, Detective 'Nine Nails' McGray's most trusted clairvoyant, hosts a séance for three of Edinburgh's wealthiest families.

The following morning everyone is found dead, with Madame Katerina being the only survivor. When questioned she alleges a tormented spirit killed the families for revenge.

McGray, even though he believes her, must find a rational explanation that holds up in court, else Katerina will be sentenced to death.

Inspector Ian Frey is summoned to help, which turns out to be difficult as he is still dealing with the loss of his uncle and has developed a form of post-traumatic stress (not yet identified in the 19th century).

This seems an impossible puzzle. Either something truly supernatural has occurred - or a fiendishly clever plot is covering a killer's tracks....

Release date: August 8, 2019

Publisher: Orion Publishing Group

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

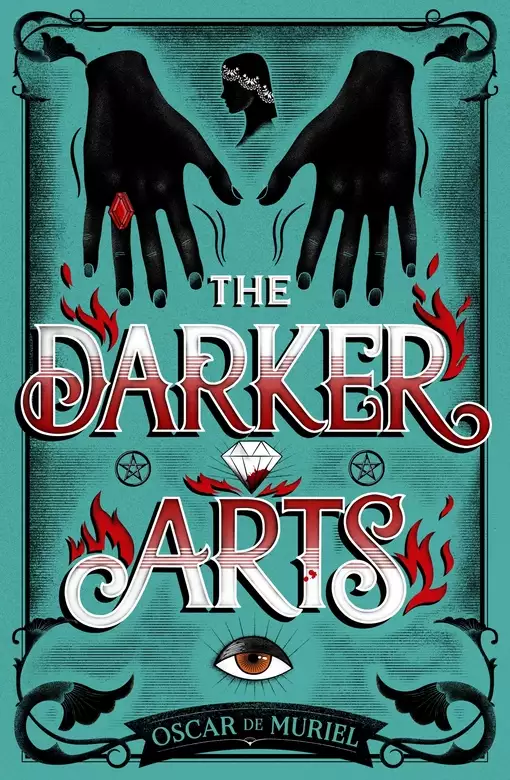

The Darker Arts

Oscar de Muriel

Doctor Clouston stepped ahead hesitantly, his footsteps deafening amidst the deathly silence of the courtroom. His hands trembled, and he had to clench them into fists to conceal his anxiety. All eyes were fixed on him, all hostile, as if he had committed the murders himself.

He took his seat at the witnesses’ box, his chin held high, took the oath, and then waited until the procurator fiscal came to him.

The man, completely bald and with a scalp as smooth and pale as polished marble, took his time, rearranging and revising documents as everyone waited in tense silence.

Clouston looked at the young Adolphus McGray, who had just given his statement. The twenty-five-year-old stood out in the rows, taller than most, broad-shouldered and with raven black hair. He also had the palest face, staring down at his bandaged hand, pressed against his chest. The wound had not fully scarred yet.

‘Doctor Thomas Clouston,’ said the procurator suddenly, making more than one at the court jump. ‘Of Edinburgh’s Royal Lunatic Asylum.’

He approached with an odious grin as he read the credentials. A lead tooth caught Clouston’s eye.

‘That is correct,’ said the doctor, taking an instant dislike to that man.

‘Can you recount the events of the evening?’

‘I am only here to testify as to the mental state of Miss McGray.’

‘Oh, indulge us, doctor.’

He spoke in grumbles. ‘I received a telegram telling me that Mr McGray and his wife had been attacked. That they were sadly dead. That their son was injured and their daughter had had to be locked up in her chambers. When I arrived—’

‘No, no, doctor,’ the procurator interrupted. ‘Before that. I would like to know what happened earlier that day.’

Clouston snorted. ‘I only know what I heard from Mr McGray’s son and servants. I do not know how a third-party statement might—’

‘Please,’ the sheriff intervened from his higher bench, ‘answer the procurator’s question.’ His ‘please’ was rather a growl.

Clouston cleared his throat. The sooner he obliged, the sooner this would be over.

‘From what I was told, Adolphus and Amy, Mr McGray’s son and daughter, left the house in the early evening. They went horseback riding since the weather was pleasant despite the hour. After some time they stopped to allow the horses to rest, and they sat by the small lake that borders their family’s estate. They chatted for a while before Miss McGray said she felt indisposed, and—’

‘Indisposed how?’

‘Again, I can only repeat what—’

‘How?’

Clouston ruffled his moustache with impatience. ‘Her brother said she complained of a headache and shortness of breath. She decided to return to the—’

‘On her own?’

‘Yes.’

‘What time was this?’

‘I must assume it was before dusk.’

‘You said they went out in the early evening. Do you believe they managed to have a ride long enough so that the mounts required rest, and then a chat, all before sunset?’

‘Are you not familiar with midsummer, Mr Pratt?’

The entire courtroom laughed, and upon the very mention of his own name, the fiscal’s lip trembled in an uncontrollable tic.

‘I simply find it odd,’ he said, ominously, ‘that a young lady would decide to ride alone, in the middle of the wilderness, when the day must have been coming to a close.’

‘It was their family’s land. The girl had probably ridden alone there countless times.’

‘And she insisted her brother stayed behind?’

‘You just heard him say so himself.’

‘A young lady, feeling ill, refuses to be accompanied back home, despite the gathering darkness. And the next thing we know is that she went berserk and killed the only two souls in the house. Do you not find it slightly suspicious?’

‘Suspicious?’

‘She was perfectly healthy when she left her brother, was she not?’

‘Yes.’

‘And mere minutes later she’d become an uncontrollable murderess?’

Adolphus stood up at this, glaring at the fiscal. The corpulent guard posted next to him pushed him back on the seat. It was not the first time the young man had lost his temper today.

Clouston took a deep breath. ‘It is an extraordinary shift, but not unheard of. The mechanics of the mind sadly remain a mystery.’

The fiscal nodded, albeit with a sardonic side smile. ‘So you sustain the plea of insanity?’

‘Indeed. The girl is under my custody now.’

‘When did you take her to your – ahem – very honourable institution?’

‘The very next day.’

‘Indeed?’

‘Yes. She was a danger to herself and others. She attacked me when I first encountered her.’

‘Oh, yes,’ the fiscal said, turning back to the audience to face Betsy, the McGrays’ stumpy, ageing maid, and George, the weathered butler. ‘As these servants said, you arrived and subdued Miss McGray without any trouble.’

Clouston inhaled, smelling a trap. ‘Yes. I did.’

The fiscal chuckled. ‘The girl managed to kill two healthy grown-ups, mutilate her brother, who, as we can see, is hardly a featherweight … yet you, doctor, never came to harm.’

Clouston stroked his long, dark beard. ‘That is true. When I arrived, Miss McGray was famished and dehydrated. The servants had locked her in her bedroom and nobody dared go near her. The poor girl had not eaten or drunk in a day. She only managed to lift a blade for an instant. She hurled herself onto me and then collapsed.’

Clouston looked at the jury with the corner of his eye. Several heads nodded.

‘Did she say anything?’ asked the fiscal. ‘Before collapsing?’

This was what everyone had been expecting. People stretched their necks and strained their ears. Some did not even blink. There were rumours already, but Clouston was the only one who’d heard the girl’s last known words.

‘Remember you are under oath, doctor,’ the fiscal pressed.

Clouston looked at Adolphus. They’d talked about this before. There was a tormented, pleading look in his blue eyes. Don’t tell them, he seemed to beg.

But he was under oath …

The doctor gulped and then spat the words.

‘She said I’m not mad …’

There were gasps and murmurs in the crowd. The fiscal walked triumphantly to the bench of the jury.

‘The girl herself said she was not mad! And if she was not mad, then these murders must be treated as—’

‘Oh, what a stupid statement!’ Clouston roared, jumping to his feet. His booming voice silenced everyone present. ‘I have treated hundreds of patients in the past twenty years. Nine out of ten will claim they’re not insane. Do you want me to believe their word and release them all at once – Mr Pratt?’

There was another wave of laughter, which turned the fiscal’s scalp bright red.

Clouston went on before the racket receded. ‘Miss McGray also said, right afterwards, that it was all the work of the devil.’

In a blink, the laughter became gasps and cries of shock. That was what people had been craving to hear. That was the statement all the papers in Dundee and Edinburgh would publish the next day.

Clouston cast Adolphus a troubled look. The young man was falling apart, clenching his bandages with his healthy hand. Clouston felt so sorry for him his heart ached – and yet, the truth had to be told …

He looked straight into the jury’s eyes. ‘Miss McGray, a dainty girl of sixteen, turned against her mother and father, whom she adored, and killed them. She became wild and had to be restrained and sedated. There is no doubt she was not herself. She …’ Clouston looked down, his voice infected with sorrow. ‘She may never be herself again.’

His words hung in the air for a long while, until the fiscal clicked his tongue.

‘A very sad tale – however inconclusive. The girl must attend court.’

‘What!’ Adolphus howled in the distance.

There were claps and cheers in the crowd, and some men were lasciviously rubbing their hands. A young woman at court always promised a good spectacle.

The procurator saw the fidgety members of the jury, whispering at each other, and he sneered. ‘I am afraid the girl’s insanity must be properly—’

‘Her insanity has been proven!’ Clouston asserted, now addressing only the sheriff and the jury. ‘My report is comprehensive. I have submitted it this morning and you can analyse it at once. A colleague from Inverness is on his way and I am certain he will only corroborate my findings. They will comply with the requirements of the Lunacy Act.’

The fiscal approached him like a stalking wolf. ‘And in the meantime you will hide a potential murderer in your institution?’

Adolphus jumped up again. ‘Ye fucking cretin!’

At a sign from the sheriff, another two guards rushed to drag him out of the courtroom. Clouston spoke even as they did so.

‘What would you have us do, Mr Pratt? Bring the girl here so she can be made a spectacle of? Nothing shall be gained other than your morbid desire to see a helpless creature publicly humiliated.’ He turned to the sheriff and jury. ‘The law is being followed. That girl has no business here. The court must show her some human compassion.’

‘Did she show any compassion to her own kin?’

There was uproar at this. People stood up, clapped, whistled and demanded the girl appeared at court. They wanted her blood ; her dignity.

Clouston felt tears of rage build up in his eyes. He pictured himself and the McGrays as caged prey, surrounded by a pack of thousands of hounds, only kept at bay by leashes that were just about to snap.

The gypsy stood by the pub’s door, swathed in a dark cape and hood. She pressed her hand, armed with curved nails painted in black, against the door, but she hesitated before going in. She looked left and right, scrutinising the Royal Mile. At this hour the cobblestoned street was deserted. Even the public house was quiet.

‘D’ye want me to go in with ye?’ her manservant asked, still at the cart’s driver seat.

‘No,’ the gypsy mumbled. ‘Wait here.’

She stepped in quietly and looked around. The place was very dark, lit only by the golden glow of some dying embers, and the air stank of cheap ale – the gypsy recognised her own brew.

There were only a few patrons left ; a mixture of the drunkest men in Edinburgh, stooped over their pints and their drams, and those plagued by disgraces no amount of drink could drown.

The McGray heir was easy to spot. Her contacts had told her he’d taken to dress in showy tartan, but even without those mismatching trousers and waistcoat, she would have recognised his tall, well-built frame from the newspaper reports.

She was expecting him to be distraught ; a sad, red-eyed figure nursing a bottle of single malt. Instead, the towering man was all over the pub’s landlady.

They were in a darkened corner of the room, locked in a tight embrace like a pair of octopuses.

The gypsy walked closer, her cloak brushing the knee of the drunkest man in the establishment.

He stared at her, his head swaying, and whistled. ‘Oi! I like a pair o’ those!’

She did not look back or break stride.

‘I’d curse you – if you had anything left to lose.’

Her well-chosen words, delivered in a strange accent from somewhere in Eastern Europe, struck her enemy’s most delicate nerve. The man looked down, attempting to hide his flushed, leathery face.

The gypsy stood firmly by the couple’s table and let out a cackle.

‘You don’t waste your time, my dear. Well done!’

The young landlady jumped up, her cheeks as red as her mane of curls. ‘Madame Katerina!’

The gypsy smiled.

‘Oh, don’t blush, Mary! At least you’re moving up in the world ; this one’s much more fetching than the wretch you asked me to jinx last month.’ She lowered her voice. ‘By the way, those warts must be sprouting nicely as we speak.’

She installed herself on Mary’s chair, and the young McGray, indignant, snapped his fingers at once.

‘Oi! I didnae say ye could sit.’

They exchanged stares in a silent duel of wills. His were light blue, hers bright green. Both cunning.

She spoke first. ‘I think you’ll like to hear what I have to tell you.’ And she unbuttoned her cloak and let it fall around her shoulders.

McGray’s eyes went directly to her protruding breasts, the largest in Edinburgh, and sported proudly under her low cleavage.

The gypsy smiled. Her attributes always threw her enemies off guard.

‘Would you like a drink, madam?’ Mary asked, before McGray managed to close his mouth.

‘Yes, my dear. But the good stuff, not the piss I sell you for the clients.’

Mary winked at her. ‘I’ll bring ye a single malt from the McGrays’ distillery. They know their trade.’ And as she made her way to the backroom, Mary exchanged a look of complicity with McGray.

He was not amused at all.

‘I don’t mean to be rude, hen,’ he said, ‘but ye should really piss off.’

‘Oh! Are you busy, my boy?’

‘Aye. I’m polishing my fuckin’ nails, don’t ye see?’

The drunkard laughed from the distance. ‘Och, ye’ll finish sooner now!’

McGray gulped down the remains of his dram and then threw the tumbler at the man. It landed right in-between his eyes and smashed to pieces. The drunkard yowled, jumped up and attempted to make a fist, but then staggered, swayed, and looked at his hand as if it were the first time he’d seen it. He shouted some vulgarity and clumsily made his way out.

‘Adolphus!’ Mary grunted, coming back with a new bottle. ‘That’s the third good client ye’ve scared away today! He could’ve downed one more bottle!’

‘I’m sure my custom will pay off, my dear,’ said Katerina, pouring herself a very generous measure. ‘And I promise you I won’t scare this one away.’

‘Yer about to do just that,’ McGray snapped.

Mary squeezed his forearm. ‘I’ll be right back, Adolphus. Do listen to Madame Katerina.’ And she scuttled into the backroom, in clear collusion with the generous-breasted gypsy.

McGray sighed. ‘What the fuck ye want?’

He interlaced his fingers. He’d only just lost the bandages, but the stitches on his finger stump, the one chopped off by his own sister, still made a grisly sight.

‘Ring finger, right hand,’ the gypsy said with a note of melancholy. ‘Just like the papers said.’

‘Aye. I’m glad I didnae lose this one – or these two.’

The gypsy smiled. ‘I like you already.’ She swirled the tumbler, sniffed the liquor and took a good swig. She winced. ‘Ahh, good stuff indeed!’

‘I hate asking things twice. What the fuck ye—?’

‘I believe your story, my boy.’

McGray looked up, his eyes catching the glow from the hearth, the blue gone a fiery amber.

‘Don’t toy with me,’ he warned, placing a hand on the table and slowly making a fist. ‘I’ve already met many quacks like ye. Youse are all after the brass with cheap tricks and lies.’

‘Don’t compare me with them, boy. I am so sorry for your losses.’

‘What d’ye care?’

She smiled wryly. ‘I know what it feels like. I lost my parents when I was very young. You’re lucky.’

‘Lucky! Aye.’

‘You have your fists and your townhouse and your distilleries …’ she indulged in the aroma of the drink. ‘I had none of that. I was a pauper girl with a funny foreign voice, all by herself. I traded anything you can imagine for a loaf of mouldy bread or a night indoors. Sometimes—’

She went silent, suddenly swallowing whichever words she was about to say. She took a long sip and cleared her throat.

‘But I made my way up in the world. I’m not desperate or helpless and I never will be again. Believe me, I’m not here to beg or take advantage. I’m here to help, even if nobody helped me when I was on the streets.’

McGray twisted his mouth in a mixture of compassion and annoyance. The gypsy smiled at that faint glimpse of empathy. That was her chance ; a crack in the young man’s shell.

‘You think you saw something,’ she whispered, her voice entrancing, like the hiss of a snake. ‘Something you can’t explain … You have even thought you might be mad yourself.’

McGray said nothing. He stared at her, not blinking, his chest swelling slowly.

‘You saw the devil, didn’t you? You saw his horns and his burned flesh. You saw him running away. Didn’t you?’

McGray drew in a troubled breath. ‘How can ye tell?’

The gypsy displayed both hands on the table, her nails like the talons of an eagle.

‘I see these things, my boy. I see that something terrible happened to your little sister. Something dark and too horrible to bear.’

A draught came in then, pushing the door ajar and making the embers quiver.

‘These things leave a trail, my boy,’ she insisted. ‘They reek. This all reeks of demons.’

McGray’s lips parted. By now everyone in Edinburgh talked of nothing but Clouston’s statement. Pansy had mentioned the devil ; it was all over the papers. He wanted to say so, to grab the woman by the arm and throw her out ; however, there was something in her eyes he could not ignore. She was looking at him with a rather motherly gaze.

She leaned closer and whispered. ‘You saw what really happened, didn’t you? You saw what I see.’

The cold from the street began to creep into McGray’s bones. Hardy as he was, he could not repress a slight shiver.

‘And there’s something else I see,’ the gypsy said at once, as if that brief tremor had lowered McGray’s guard. She smiled, but it was a warm, relieved smile. ‘Your little sister may not be lost. Not yet.’

McGray tensed his entire body ; that stiffness felt like a shield that somehow kept the gypsy at bay. Here was this woman, telling him the very words he so desperately yearned to hear. All the more reason to remain cautious.

He said nothing, and the woman leaned closer. Her eyes too were like embers.

‘I can help you.’

McGray raised his chin, clenching his fist more tightly. And yet, he could not look away.

The gypsy smiled wider.

‘We can help each other.’

11.30 p.m.

‘Your damn gypsy is late,’ Colonel Grenville barked, staring out the window at the gloomy gardens. His teeth had been clenching the cigar so tightly his mouth was now full of bits of crushed tobacco. He spat them as he turned back to the darkened room, but the sight of the others only worsened his temper.

Leonora was hunched over her blasted book of necromancy and related nonsense, and the many candles on the round table cast sharp shadows on her gaunt face.

‘She will come,’ said the twenty-two-year-old with her dreamy airs, as if intent on looking like an apparition herself. Colonel Grenville thought the silly girl deserved a good smack, fancying herself a consummate fortune teller.

Mrs Grenville, at the edge of a nearby sofa, fanned herself anxiously, the insistent ruffle of the feathers the only sound in the tense parlour. She cast a fearful look at her husband – the colonel had seldom been made to wait. Even when asked to marry him, she had been shaken and forced to provide an answer with military promptness. She’d thought it so romantic back then. Now, though …

She let out a tired sigh.

The old Mr Shaw, her grandfather, sat rather stiff by her side. The man’s white beard and whiskers, and the golden frames of his round spectacles gleamed under the candlelight, but little else of him could be seen. Like a spectre, he brought an infirm hand to the light and grasped his daughter’s wrist, forcing her fan into stillness.

‘Thanks, Hector,’ said a hoarse voice from the depth of the shadows. The voice of a man the colonel despised : Mr Willberg, clad in black and almost invisible standing in a darkened corner. The man took a few steps into the light, as if materialising from nowhere, and began pacing. Peter Willberg was almost a decade older than the colonel, and the only man present who’d dare challenge him. Colonel Grenville knew this, and glared at Willberg’s bushy beard, which was curly and jet black, even if the hair on his scalp was thin and growing white.

‘You’ll have to ask someone to clean that,’ Mr Willberg told the colonel, nodding at the flakes of tobacco on the red carpet.

‘Go to hell, Pete,’ snapped Colonel Grenville. ‘This is my bloody house!’

Mr Willberg sneered. ‘Oh, is it now?’

Nobody spoke. They simply waited for the colonel’s reaction. Leonora was the only one who moved, stretching an arm to squeeze Mr Willberg’s. Her eyes pleaded for his composure.

Defiantly, the colonel tossed his cigar onto the floor and produced a new one from his pocket.

‘The last thing we need is more bloody smoke, you fool!’ Mr Willberg snapped.

In that at least they all agreed. The air in the small chamber was thick, with wafts of sickly smoke floating in-between the flickering flames.

The colonel roared, ‘Then tell your bloody niece to put those damn things out!’

‘We need to cleanse the room!’ Leonora cried just as loudly, raising her arms as if readying herself to defend the set of candles. The same ones her grandmother had blessed so many years ago, which were – according to the gypsy – key to their success tonight. ‘We need them to talk to the dead!’

‘There, there,’ said the old Mr Shaw, applying an already damp handkerchief to his forehead. ‘We are all … we are all very tense.’

They all sensed the fear in his voice, and at once fell silent. If the séance succeeded, the poor old man was about to face demons none of the others could even imagine. Mrs Grenville placed a hand on her father’s, but the man twitched and pulled it away.

‘Is that scaredy-cat Bertrand ready?’ the colonel asked.

At once, a tiny voice came from the parlour’s door. Bertrand had been standing next to the door frame.

‘A – aye. I’m here, sir, sorry. The room is stifling.’

The colonel snorted as he cast him a derisive look. Bertrand embodied everything he hated in men : he was weak, sheepish, soft in the knees, with a squeaky voice and fidgety hands he always rubbed by his chest. Many times the colonel had remarked on Bertrand’s apparent lack of gonads – more than once to his face, but the stupid fella simply giggled as if it all were a joke. His manners might be childish, yet the chap was not even young ; his oily hair, always parted and flattened with obsessive care, was already going grey at the top. The colonel’s wife was Bertrand’s first cousin, and it still infuriated him that his three children shared blood with such a gritless oaf.

‘Here she comes!’ said Mr Willberg, peering through the window.

Bertrand squinted, for he’d feared the prospect all along. He was present only because his Aunt Gertrude had backed down that very morning and, according to that gypsy woman, the ceremony needed seven souls.

Mrs Grenville stood up, fidgeting with the pearls of her choker, and saw the light of the coach approaching through the gardens. The night was so dark, the sky lined with clouds so dense, that it looked as though the carriage floated amidst an endless void.

She went closer to the window. Her shoulder accidentally rubbed Mr Willberg’s, and they both flinched. She’d never seen the man thus altered, his customary stench of ale stronger than usual.

The colonel brusquely pushed her aside to have a look, and saw Holt, his fleshy valet, jumping off the driver’s seat and helping down what looked like a bundle of extravagant curtains.

Soon enough, Holt entered the parlour, and when the gypsy came in, everyone froze still. It would take them a moment to scrutinise the woman, and even the colonel had to admit there was something unnerving about her.

She was squat, solidly built, wrapped in countless multicoloured shawls, scarves and veils. Nobody could see her face, shrouded in black tulle trimmed with cheap pendants, which tinkled softly at her every movement. The many layers of fabric gave off a pungent herbal smell, strong enough to overpower the parlour’s mist. Her hands were wrapped in black mittens, so all that could be seen of her were the tips of her stout, pale fingers, each one armed with curved nails – she moved them slowly, as if drumming on an invisible table.

The young Leonora jumped to her feet and ran to the woman, reaching for one of those menacing hands.

‘Madame Katerina, it’s an honour! I knew you’d come.’

‘I always go to those who need me,’ she replied with a hoarse, foreign voice.

‘Or who pay you,’ the colonel said between his teeth.

Leonora turned to him, ready to retort, but the gypsy grasped her arm.

‘Leave it, child. This room is already quite disturbed.’

‘Oh, but I cleansed it as you said, madam! Like Grannie Alice herself would have done.’

The colonel went to Holt and barked at him. ‘What took you so long?’

Holt had barely opened his mouth when the gypsy answered herself.

‘I was in the middle of something else.’

The colonel let out a loud ‘HA!’ which the gypsy ignored. She pulled off one of her mittens, rested a palm on the wall, and leisurely ran her hand on the oak panelling. Her long fingernails, painted in black, shimmered under the candlelight. She then turned to Leonora.

‘You did well, girl. We can do the rituals here … but only just.’ She came closer to the table and candles, and the light went through her veil’s thin material. They all managed to see the twinkle of her cunning eyes, going from one person to the other. She only spoke again once she had studied them all. ‘Yes, only just. There’s too much guilt here.’

Those words caused more than one gulp.

‘The chairs, Bertrand!’ snapped Mr Willberg, and the fidgety man, after a jump, began dragging seats from the adjacent dining room. The screech of the wood proved unbearable for the old Mr Shaw, and his grandaughter had to go to him and hold his hand.

Leonora led Madame Katerina to the little round table. ‘We dispatched the servants, ma’am. They were all gone before sunset, just as you requested.’

The woman assented, casting an approving look at the table.

Bertrand placed the seventh chair and Leonora offered a seat to the gypsy, as reverently as if addressing Queen Victoria. The woman sat down as Bertrand brought a tripod and installed it clumsily by the window.

‘What’s that for?’ she said. ‘A camera?’

Leonora sat by her side, her eyes burning with excitement. ‘Oh, do, do humour me, ma’am. I want photos of this session. I read the spirits sometimes show in the plaques.’

The gypsy remained silent, her face inscrutable. ‘I never heard such a thing.’

‘Do you not like to leave evidence behind?’ said the colonel, sitting next to the clairvoyant. He puffed at his cigar with an insolent look.

The gypsy set her hands on the table, as she liked to do to prove she was in command of the situation. ‘No more than you do, little man.’

The colonel made to stand up, dropping his cigar on the floor. It was Mr Willberg’s hand that pushed him back down.

‘Will you stop it, Grenville? You of all people here—’

‘Oh, save it, Pete!’

Mrs Grenville sat next to her husband but did not say a word. She knew any attempt to calm him down only enraged him further.

‘Do you have the offerings?’ the gypsy asked.

‘Of course,’ replied Leonora, already rushing to a side cabinet. She brought a cut-glass decanter that made Holt shudder. It seemed to contain blood.

As if feeling his agitation, the clairvoyant turned her head towards him. ‘He has to leave.’

The colonel let out an impatient sigh, rose and dragged Holt out of the parlour. The middle-aged valet could only be relieved.

‘Here,’ the colonel said as he pulled a generous amount of notes from his pocket. ‘More than I promised. If you intend to spend it on beer or women, make sure it is not tonight. I need you here in the morning.’

‘Of course, sir,’ replied Holt, barely repressing the urge to count the money. ‘What time do you need me back?’

‘Break of dawn,’ he said, and he then clasped Holt’s collar. ‘Not a damn minute late. The sooner I get all these vermin out of my house, the better.’

Holt had always wanted to spit on the man’s face, but the colonel paid too handsomely, so he simply bowed.

‘I won’t fail you, sir.’

Colonel Grenville straightened his jacket, casting Holt a warning stare, and went back into the parlour.

As he shut the door, Holt strived to catch a last glimpse of the young Leonora, setting up the photographic camera. He also saw the nervous faces gathered round the table and the dark liquid in the decanter amidst the candles.

He pocketed the money and went straight to the carriage. Just as he crossed the garden gates, Holt cast a last look at the façade. He saw a flicker of intense light coming from the parlour’s window, surely from the camera’s flash powder. After that, the room went as dark as a grave, like all the others in the empty house. Holt thought he’d heard a hoarse, deep growl coming from the parlour, and felt a shiver.

The colonel had told him nothing about that meeting, but Holt knew the family far too well. Something monstrous was about to happen within that room. Something far too horrible to be spoken out loud.

The less he knew, the better.

Cut out from The Scotsman

Saturday 14 September 1889, afternoon issue

THE DAWNING HORROR OF MORNINGSIDE :SIX DEAD

The genteel neighbourhood of Morningside awoke to sheer horror when Mr Alexander Holt

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...