- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

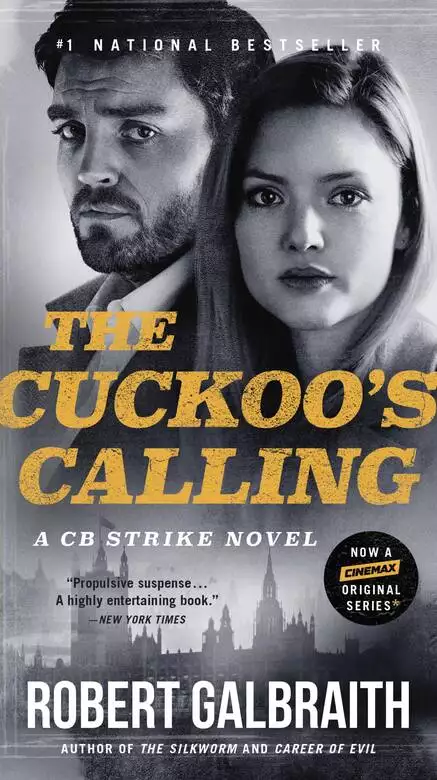

A brilliant mystery in a classic vein: Detective Cormoran Strike investigates a supermodel’s suicide.

After losing his leg to a land mine in Afghanistan, Cormoran Strike is barely scraping by as a private investigator. Strike is down to one client, and creditors are calling. He has also just broken up with his longtime girlfriend and is now living in his office.

Then John Bristow walks through his door with an amazing story: his sister, the legendary supermodel Lula Landry, known to her friends as the Cuckoo, famously fell to her death a few months earlier. The police ruled it a suicide, but John refuses to believe that. The case plunges Strike into the world of multimillionaire beauties, rock-star boyfriends, and desperate designers, and it introduces him to every variety of pleasure, enticement, seduction, and delusion known to man.

You may think you know detectives, but you’ve never met one quite like Strike. You may think you know about the wealthy and famous, but you’ve never seen them under an investigation like this.

Release date: April 30, 2013

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 464

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Cuckoo's Calling

Robert Galbraith

Behind the tightly packed paparazzi stood white vans with enormous satellite dishes on the roofs, and journalists talking, some in foreign languages, while soundmen in headphones hovered. Between recordings, the reporters stamped their feet and warmed their hands on hot beakers of coffee from the teeming café a few streets away. To fill the time, the woolly-hatted cameramen filmed the backs of the photographers, the balcony, the tent concealing the body, then repositioned themselves for wide shots that encompassed the chaos that had exploded inside the sedate and snowy Mayfair street, with its lines of glossy black doors framed by white stone porticos and flanked by topiary shrubs. The entrance to number 18 was bounded with tape. Police officials, some of them white-clothed forensic experts, could be glimpsed in the hallway beyond.

The television stations had already had the news for several hours. Members of the public were crowding at either end of the road, held at bay by more police; some had come, on purpose, to look, others had paused on their way to work. Many held mobile telephones aloft to take pictures before moving on. One young man, not knowing which was the crucial balcony, photographed each of them in turn, even though the middle one was packed with a row of shrubs, three neat, leafy orbs, which barely left room for a human being.

A group of young girls had brought flowers, and were filmed handing them to the police, who as yet had not decided on a place for them, but laid them self-consciously in the back of the police van, aware of camera lenses following their every move.

The correspondents sent by twenty-four-hour news channels kept up a steady stream of comment and speculation around the few sensational facts they knew.

“…from her penthouse apartment at around two o’clock this morning. Police were alerted by the building’s security guard…”

“…no sign yet that they are moving the body, which has led some to speculate…”

“…no word on whether she was alone when she fell…”

“…teams have entered the building and will be conducting a thorough search.”

A chilly light filled the interior of the tent. Two men were crouching beside the body, ready to move it, at last, into a body bag. Her head had bled a little into the snow. The face was crushed and swollen, one eye reduced to a pucker, the other showing as a sliver of dull white between distended lids. When the sequined top she wore glittered in slight changes of light, it gave a disquieting impression of movement, as though she breathed again, or was tensing muscles, ready to rise. The snow fell with soft fingertip plunks on the canvas overhead.

“Where’s the bloody ambulance?”

Detective Inspector Roy Carver’s temper was mounting. A paunchy man with a face the color of corned beef, whose shirts were usually ringed with sweat around the armpits, his short supply of patience had been exhausted hours ago. He had been here nearly as long as the corpse; his feet were so cold that he could no longer feel them, and he was light-headed with hunger.

“Ambulance is two minutes away,” said Detective Sergeant Eric Wardle, unintentionally answering his superior’s question as he entered the tent with his mobile pressed to his ear. “Just been organizing a space for it.”

Carver grunted. His bad temper was exacerbated by the conviction that Wardle was excited by the presence of the photographers. Boyishly good-looking, with thick, wavy brown hair now frosted with snow, Wardle had, in Carver’s opinion, dawdled on their few forays outside the tent.

“At least that lot’ll shift once the body’s gone,” said Wardle, still looking out at the photographers.

“They won’t go while we’re still treating the place like a fucking murder scene,” snapped Carver.

Wardle did not answer the unspoken challenge. Carver exploded anyway.

“The poor cow jumped. There was no one else there. Your so-called witness was coked out of her—”

“It’s coming,” said Wardle, and to Carver’s disgust, he slipped back out of the tent, to wait for the ambulance in full sight of the cameras.

The story forced news of politics, wars and disasters aside, and every version of it sparkled with pictures of the dead woman’s flawless face, her lithe and sculpted body. Within hours, the few known facts had spread like a virus to millions: the public row with the famous boyfriend, the journey home alone, the overheard screaming and the final, fatal fall…

The boyfriend fled into a rehab facility, but the police remained inscrutable; those who had been with her on the evening before her death were hounded; thousands of columns of newsprint were filled, and hours of television news, and the woman who swore she had overheard a second argument moments before the body fell became briefly famous too, and was awarded smaller-sized photographs beside the images of the beautiful dead girl.

But then, to an almost audible groan of disappointment, the witness was proven to have lied, and she retreated into rehab, and the famous prime suspect emerged, as the man and the lady in a weather-house who can never be outside at the same time.

So it was suicide after all, and after a moment’s stunned hiatus, the story gained a weak second wind. They wrote that she was unbalanced, unstable, unsuited to the superstardom her wildness and her beauty had snared; that she had moved among an immoral moneyed class that had corrupted her; that the decadence of her new life had unhinged an already fragile personality. She became a morality tale stiff with Schadenfreude, and so many columnists made allusion to Icarus that Private Eye ran a special column.

And then, at last, the frenzy wore itself into staleness, and even the journalists had nothing left to say, but that too much had been said already.

1

THOUGH ROBIN ELLACOTT’S TWENTY-FIVE YEARS of life had seen their moments of drama and incident, she had never before woken up in the certain knowledge that she would remember the coming day for as long as she lived.

Shortly after midnight, her long-term boyfriend, Matthew, had proposed to her under the statue of Eros in the middle of Piccadilly Circus. In the giddy relief following her acceptance, he confessed that he had been planning to pop the question in the Thai restaurant where they just had eaten dinner, but that he had reckoned without the silent couple beside them, who had eavesdropped on their entire conversation. He had therefore suggested a walk through the darkening streets, in spite of Robin’s protests that they both needed to be up early, and finally inspiration had seized him, and he had led her, bewildered, to the steps of the statue. There, flinging discretion to the chilly wind (in a most un-Matthew-like way), he had proposed, on one knee, in front of three down-and-outs huddled on the steps, sharing what looked like a bottle of meths.

It had been, in Robin’s view, the most perfect proposal, ever, in the history of matrimony. He had even had a ring in his pocket, which she was now wearing; a sapphire with two diamonds, it fitted perfectly, and all the way into town she kept staring at it on her hand as it rested on her lap. She and Matthew had a story to tell now, a funny family story, the kind you told your children, in which his planning (she loved that he had planned it) went awry, and turned into something spontaneous. She loved the tramps, and the moon, and Matthew, panicky and flustered, on one knee; she loved Eros, and dirty old Piccadilly, and the black cab they had taken home to Clapham. She was, in fact, not far off loving the whole of London, which she had not so far warmed to, during the month she had lived there. Even the pale and pugnacious commuters squashed into the Tube carriage around her were gilded by the radiance of the ring, and as she emerged into the chilly March daylight at Tottenham Court Road underground station, she stroked the underside of the platinum band with her thumb, and experienced an explosion of happiness at the thought that she might buy some bridal magazines at lunchtime.

Male eyes lingered on her as she picked her way through the road-works at the top of Oxford Street, consulting a piece of paper in her right hand. Robin was, by any standards, a pretty girl; tall and curvaceous, with long strawberry-blonde hair that rippled as she strode briskly along, the chill air adding color to her pale cheeks. This was the first day of a week-long secretarial assignment. She had been temping ever since coming to live with Matthew in London, though not for much longer; she had what she termed “proper” interviews lined up now.

The most challenging part of these uninspiring piecemeal jobs was often finding the offices. London, after the small town in Yorkshire she had left, felt vast, complex and impenetrable. Matthew had told her not to walk around with her nose in an A–Z, which would make her look like a tourist and render her vulnerable; she therefore relied, as often as not, on poorly hand-drawn maps that somebody at the temping agency had made for her. She was not convinced that this made her look more like a native-born Londoner.

The metal barricades and the blue plastic Corimec walls surrounding the roadworks made it much harder to see where she ought to be going, because they obscured half the landmarks drawn on the paper in her hand. She crossed the torn-up road in front of a towering office block, labeled “Center Point” on her map, which resembled a gigantic concrete waffle with its dense grid of uniform square windows, and made her way in the rough direction of Denmark Street.

She found it almost accidentally, following a narrow alleyway called Denmark Place out into a short street full of colorful shop fronts: windows full of guitars, keyboards and every kind of musical ephemera. Red and white barricades surrounded another open hole in the road, and workmen in fluorescent jackets greeted her with early-morning wolf-whistles, which Robin pretended not to hear.

She consulted her watch. Having allowed her usual margin of time for getting lost, she was a quarter of an hour early. The nondescript black-painted doorway of the office she sought stood to the left of the 12 Bar Café; the name of the occupant of the office was written on a scrappy piece of lined paper taped beside the buzzer for the second floor. On an ordinary day, without the brand-new ring glittering upon her finger, she might have found this off-putting; today, however, the dirty paper and the peeling paint on the door were, like the tramps from last night, mere picturesque details on the backdrop of her grand romance. She checked her watch again (the sapphire glittered and her heart leapt; she would watch that stone glitter all the rest of her life), then decided, in a burst of euphoria, to go up early and show herself keen for a job that did not matter in the slightest.

She had just reached for the bell when the black door flew open from the inside, and a woman burst out on to the street. For one strangely static second the two of them looked directly into each other’s eyes, as each braced to withstand a collision. Robin’s senses were unusually receptive on this enchanted morning; the split-second view of that white face made such an impression on her that she thought, moments later, when they had managed to dodge each other, missing contact by a centimeter, after the dark woman had hurried off down the street, around the corner and out of sight, that she could have drawn her perfectly from memory. It was not merely the extraordinary beauty of the face that had impressed itself on her memory, but the other’s expression: livid, yet strangely exhilarated.

Robin caught the door before it closed on the dingy stairwell. An old-fashioned metal staircase spiraled up around an equally antiquated birdcage lift. Concentrating on keeping her high heels from catching in the metalwork stairs, she proceeded to the first landing, passing a door carrying a laminated and framed poster saying Crowdy Graphics, and continued climbing. It was only when she reached the glass door on the floor above that Robin realized, for the first time, what kind of business she had been sent to assist. Nobody at the agency had said. The name on the paper beside the outside buzzer was engraved on the glass panel: C. B. Strike, and, underneath it, the words Private Detective.

Robin stood quite still, with her mouth slightly open, experiencing a moment of wonder that nobody who knew her could have understood. She had never confided in a solitary human being (even Matthew) her lifelong, secret, childish ambition. For this to happen today, of all days! It felt like a wink from God (and this too she somehow connected with the magic of the day; with Matthew, and the ring; even though, properly considered, they had no connection at all).

Savoring the moment, she approached the engraved door very slowly. She stretched out her left hand (sapphire dark, now, in this dim light) towards the handle; but before she had touched it, the glass door too flew open.

This time, there was no near-miss. Sixteen unseeing stone of disheveled male slammed into her; Robin was knocked off her feet and catapulted backwards, handbag flying, arms windmilling, towards the void beyond the lethal staircase.

2

STRIKE ABSORBED THE IMPACT, HEARD the high-pitched scream and reacted instinctively: throwing out a long arm, he seized a fistful of cloth and flesh; a second shriek of pain echoed around the stone walls and then, with a wrench and a tussle, he had succeeded in dragging the girl back on to firm ground. Her shrieks were still echoing off the walls, and he realized that he himself had bellowed, “Jesus Christ!”

The girl was doubled up in pain against the office door, whimpering. Judging by the lopsided way she was hunched, with one hand buried deep under the lapel of her coat, Strike deduced that he had saved her by grabbing a substantial part of her left breast. A thick, wavy curtain of bright blonde hair hid most of the girl’s blushing face, but Strike could see tears of pain leaking out of one uncovered eye.

“Fuck—sorry!” His loud voice reverberated around the stairwell. “I didn’t see you—didn’t expect anyone to be there…”

From under their feet, the strange and solitary graphic designer who inhabited the office below yelled, “What’s happening up there?” and a second later, a muffled complaint from above indicated that the manager of the bar downstairs, who slept in an attic flat over Strike’s office, had also been disturbed—perhaps woken—by the noise.

“Come in here…”

Strike pushed open the door with his fingertips, so as to have no accidental contact with her while she stood huddled against it, and ushered her into the office.

“Is everything all right?” called the graphic designer querulously.

Strike slammed the office door behind him.

“I’m OK,” lied Robin, in a quavering voice, still hunched over with her hand on her chest, her back to him. After a second or two, she straightened up and turned around, her face scarlet and her eyes still wet.

Her accidental assailant was massive; his height, his general hairiness, coupled with a gently expanding belly, suggested a grizzly bear. One of his eyes was puffy and bruised, the skin just below the eyebrow cut. Congealing blood sat in raised white-edged nail tracks on his left cheek and the right side of his thick neck, revealed by the crumpled open collar of his shirt.

“Are you M-Mr. Strike?”

“Yeah.”

“I-I’m the temp.”

“The what?”

“The temp. From Temporary Solutions?”

The name of the agency did not wipe the incredulous look from his battered face. They stared at each other, unnerved and antagonistic.

Just like Robin, Cormoran Strike knew that he would forever remember the last twelve hours as an epoch-changing night in his life. Now, it seemed, the Fates had sent an emissary in a neat beige trench coat, to taunt him with the fact that his life was bubbling towards catastrophe. There was not supposed to be a temp. He had intended his dismissal of Robin’s predecessor to end his contract.

“How long have they sent you for?”

“A-a week to begin with,” said Robin, who had never been greeted with such a lack of enthusiasm.

Strike made a rapid mental calculation. A week at the agency’s exorbitant rate would drive his overdraft yet further into the region of irreparable; it might even be the final straw his main creditor kept implying he was waiting for.

“ ’Scuse me a moment.”

He left the room via the glass door, and turned immediately right, into a tiny dank toilet. Here he bolted the door, and stared into the cracked, spotted mirror over the sink.

The reflection staring back at him was not handsome. Strike had the high, bulging forehead, broad nose and thick brows of a young Beethoven who had taken to boxing, an impression only heightened by the swelling and blackening eye. His thick curly hair, springy as carpet, had ensured that his many youthful nicknames had included “Pubehead.” He looked older than his thirty-five years.

Ramming the plug into the hole, he filled the cracked and grubby sink with cold water, took a deep breath and completely submerged his throbbing head. Displaced water slopped over his shoes, but he ignored it for the relief of ten seconds of icy, blind stillness.

Disparate images of the previous night flickered through his mind: emptying three drawers of possessions into a kitbag while Charlotte screamed at him; the ashtray catching him on the brow-bone as he looked back at her from the door; the journey on foot across the dark city to his office, where he had slept for an hour or two in his desk chair. Then the final, filthy scene, after Charlotte had tracked him down in the early hours, to plunge in those last few banderillas she had failed to implant before he had left her flat; his resolution to let her go when, after clawing his face, she had run out of the door; and then that moment of madness when he had plunged after her—a pursuit ended as quickly as it had begun, with the unwitting intervention of this heedless, superfluous girl, whom he had been forced to save, and then placate.

He emerged from the cold water with a gasp and a grunt, his face and head pleasantly numb and tingling. With the cardboard-textured towel that hung on the back of the door he rubbed himself dry and stared again at his grim reflection. The scratches, washed clean of blood, looked like nothing more than the impressions of a crumpled pillow. Charlotte would have reached the underground by now. One of the insane thoughts that had propelled him after her had been fear that she would throw herself on the tracks. Once, after a particularly vicious row in their mid-twenties, she had climbed on to a rooftop, where she had swayed drunkenly, vowing to jump. Perhaps he ought to be glad that the Temporary Solution had forced him to abandon the chase. There could be no going back from the scene in the early hours of this morning. This time, it had to be over.

Tugging his sodden collar away from his neck, Strike pulled back the rusty bolt and headed out of the toilet and back through the glass door.

A pneumatic drill had started up in the street outside. Robin was standing in front of the desk with her back to the door; she whipped her hand back out of the front of her coat as he re-entered the room, and he knew that she had been massaging her breast again.

“Is—are you all right?” Strike asked, carefully not looking at the site of the injury.

“I’m fine. Listen, if you don’t need me, I’ll go,” said Robin with dignity.

“No—no, not at all,” said a voice issuing from Strike’s mouth, though he listened to it with disgust. “A week—yeah, that’ll be fine. Er—the post’s here…” He scooped it from the doormat as he spoke and scattered it on the bare desk in front of her, a propitiatory offering. “Yeah, if you could open that, answer the phone, generally sort of tidy up—computer password’s Hatherill23, I’ll write it down…” This he did, under her wary, doubtful gaze. “There you go—I’ll be in here.”

He strode into the inner office, closed the door carefully behind him and then stood quite still, gazing at the kitbag under the bare desk. It contained everything he owned, for he doubted that he would ever see again the nine tenths of his possessions he had left at Charlotte’s. They would probably be gone by lunchtime; set on fire, dumped in the street, slashed and crushed, doused in bleach. The drill hammered relentlessly in the street below.

And now the impossibility of paying off his mountainous debts, the appalling consequences that would attend the imminent failure of this business, the looming, unknown but inevitably horrible sequel to his leaving Charlotte; in Strike’s exhaustion, the misery of it all seemed to rear up in front of him in a kind of kaleidoscope of horror.

Hardly aware that he had moved, he found himself back in the chair in which he had spent the latter part of the night. From the other side of the insubstantial partition wall came muffled sounds of movement. The Temporary Solution was no doubt starting up the computer, and would shortly discover that he had not received a single work-related email in three weeks. Then, at his own request, she would start opening all his final demands. Exhausted, sore and hungry, Strike slid face down on to the desk again, muffling his eyes and ears in his encircling arms, so that he did not have to listen while his humiliation was laid bare next door by a stranger.

3

FIVE MINUTES LATER THERE WAS a knock on the door and Strike, who had been on the verge of sleep, jerked upright in his chair.

“Sorry?”

His subconscious had become entangled with Charlotte again; it was a surprise to see the strange girl enter the room. She had taken off her coat to reveal a snugly, even seductively fitting cream sweater. Strike addressed her hairline.

“Yeah?”

“There’s a client here for you. Shall I show him in?”

“There’s a what?”

“A client, Mr. Strike.”

He looked at her for several seconds, trying to process the information.

“Right, OK—no, give me a couple of minutes, please, Sandra, and then show him in.”

She withdrew without comment.

Strike wasted barely a second on asking himself why he had called her Sandra, before leaping to his feet and setting about looking and smelling less like a man who had slept in his clothes. Diving under his desk into his kitbag, he seized a tube of toothpaste, and squeezed three inches into his open mouth; then he noticed that his tie was soaked in water from the sink, and that his shirt front was spattered with flecks of blood, so he ripped both off, buttons pinging off the walls and filing cabinet, dragged a clean though heavily creased shirt out of the kitbag instead and pulled it on, thick fingers fumbling. After stuffing the kitbag out of sight behind his empty filing cabinet, he hastily reseated himself and checked the inner corners of his eyes for debris, all the while wondering whether this so-called client was the real thing, and whether he would be prepared to pay actual money for detective services. Strike had come to realize, over the course of an eighteen-month spiral into financial ruin, that neither of these things could be taken for granted. He was still chasing two clients for full payment of their bills; a third had refused to disburse a penny, because Strike’s findings had not been to his taste, and given that he was sliding ever deeper into debt, and that a rent review of the area was threatening his tenancy of the central London office that he had been so pleased to secure, Strike was in no position to involve a lawyer. Rougher, cruder methods of debt collection had become a staple of his recent fantasies; it would have given him much pleasure to watch the smuggest of his defaulters cowering in the shadow of a baseball bat.

The door opened again; Strike hastily removed his index finger from his nostril and sat up straight, trying to look bright and alert in his chair.

“Mr. Strike, this is Mr. Bristow.”

The prospective client followed Robin into the room. The immediate impression was favorable. The stranger might be distinctly rabbity in appearance, with a short upper lip that failed to conceal large front teeth; his coloring was sandy, and his eyes, judging by the thickness of his glasses, myopic; but his dark gray suit was beautifully tailored, and the shining ice-blue tie, the watch and the shoes all looked expensive.

The snowy smoothness of the stranger’s shirt made Strike doubly conscious of the thousand or so creases in his own clothes. He stood up to give Bristow the full benefit of his six feet three inches, held out a hairy-backed hand and attempted to counter his visitor’s sartorial superiority by projecting the air of a man too busy to worry about laundry.

“Cormoran Strike; how d’you do.”

“John Bristow,” said the other, shaking hands. His voice was pleasant, cultivated and uncertain. His gaze lingered on Strike’s swollen eye.

“Could I offer you gentlemen some tea or coffee?” asked Robin.

Bristow asked for a small black coffee, but Strike did not answer; he had just caught sight of a heavy-browed young woman in a frumpy tweed suit, who was sitting on the threadbare sofa beside the door of the outer office. It beggared belief that two potential clients could have arrived at the same moment. Surely he had not been sent a second temp?

“And you, Mr. Strike?” asked Robin.

“What? Oh—black coffee, two sugars, please, Sandra,” he said, before he could stop himself. He saw her mouth twist as she closed the door behind her, and only then did he remember that he did not have any coffee, sugar or, indeed, cups.

Sitting down at Strike’s invitation, Bristow looked round the tatty office in what Strike was afraid was disappointment. The prospective client seemed nervous in the guilty way that Strike had come to associate with suspicious husbands, yet a faint air of authority clung to him, conveyed mainly by the obvious expense of his suit. Strike wondered how Bristow had found him. It was hard to get word-of-mouth business when your only client (as she regularly sobbed down the telephone) had no friends.

“What can I do for you, Mr. Bristow?” he asked, back in his own chair.

“It’s—um—actually, I wonder whether I could just check…I think we’ve met before.”

“Really?”

“You wouldn’t remember me, it was years and years ago…but I think you were friends with my brother Charlie. Charlie Bristow? He died—in an accident—when he was nine.”

“Bloody hell,” said Strike. “Charlie…yeah, I remember.”

And, indeed, he remembered perfectly. Charlie Bristow had been one of many friends Strike had collected during a complicated, peripatetic childhood. A magnetic, wild and reckless boy, pack leader of the coolest gang at Strike’s new school in London, Charlie had taken one look at the enormous new boy with the thick Cornish accent, and appointed him his best friend and lieutenant. Two giddy months of bosom friendship and bad behavior had followed. Strike, who had always been fascinated by the smooth workings of other children’s homes, with their sane, well-ordered families, and the bedrooms they were allowed to keep for years and years, retained a vivid memory of Charlie’s house, which had been large and luxurious. There had been a long sunlit lawn, a tree house, and iced lemon squash served by Charlie’s mother.

And then had come the unprecedented horror of the first day back at school after Easter break, when their form teacher had told them that Charlie would never return, that he was dead, that he had ridden his bike over the edge of a quarry, while holidaying in Wales. She had been a mean old bitch, that teacher, and she had not been able to resist telling the class that Charlie, who as they would remember often disobeyed grown-ups, had been expressly forbidden to ride anywhere near the quarry, but that he had done so anyway, perhaps showing off—but she had been forced to stop there, because two little girls in the front row were sobbing.

From that day onwards, Strike had seen the face of a laughing blond boy fragmenting every time he looked at, or imagined, a quarry. He would not have been surprised if every member of Charlie Bristow’s old class had been left with the same lingering fear of the great dark pit, the sheer drop and the unforgiving stone.

“Yeah, I remember Charlie,” he said.

Bristow’s Adam’s apple bobbed a little.

“Yes. Well it’s your name, you see. I remember so clearly Charlie talking about you, on holiday, in the days before he died; ‘my friend Strike,’ ‘Cormoran Strike.’ It’s unusual, isn’t it? Where does ‘Strike’ come from, do you know? I’ve never met it anywhere else.”

Bristow was not the first person Strike had known who would snatch at any procrastinatory subject—the weather, the congestion charge, their preferences in hot dri

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...