- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

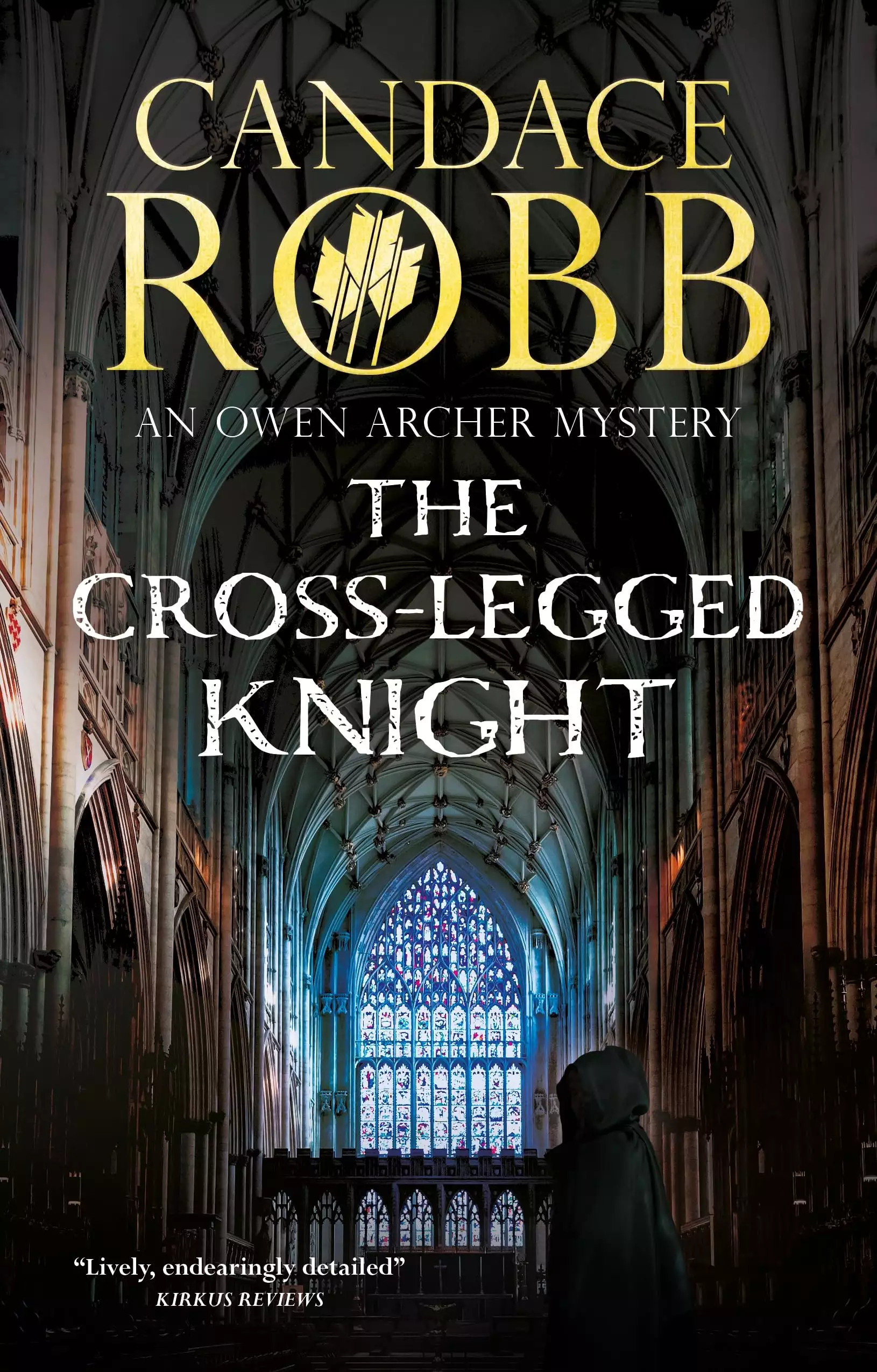

Synopsis

Will the death of a prominent knight lead to the Bishop of Winchester's downfall? Owen Archer investigates threats, scandal and murder after Sir Ranulf Pagnell dies in France.

York, 1371. William of Wykeham, Bishop of Winchester, has made many enemies since York knight Sir Ranulf Pagnell died imprisoned in France while Wykeham negotiated his ransom. After escorting Sir Ranulf's body back to the city, Wykeham realises that his own life is in grave danger.

VENGEANCE IS COMING . . .

The bishop's woes increase when one of his properties in the city is set alight, with horrific consequences. Was it a thoughtless act of revenge or a deliberate murder? Why was someone searching for important documents in the house just before the fire, including those linked to the Pagnells?

A DEADLY DECEPTION.

As Owen investigates, he uncovers a shocking secret linked to Sir Ranulf's terrible fate. A secret someone is prepared to go to any lengths to keep hidden . . .

Release date: February 6, 2024

Publisher: Severn House

Print pages: 386

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Cross-Legged Knight

Candace Robb

PROLOGUE

October 1371

William of Wykeham, bishop of Winchester and late lord chancellor of England, sat in the mottled shade of Archbishop Thoresby’s rose arbor wiping his irritated eyes and cursing all that had brought him riding to York four days ago. The horses’ hooves had stirred up summer’s dust and the mold from the autumn leaves. He and his entourage had ridden with cloths covering their faces from their chins to the bridges of their noses. Wykeham might have pampered himself within the curtains of a litter, but he had not wished anyone to misconstrue such a nicety, spreading word that he had hidden from the curious along the way, or, worse yet, that he was ill, weak. So he had ridden north on the King’s Highway with his men, regretting that the rains of autumn had held off for his journey to York.

They had stopped frequently and broken their journey early in the evenings. Wykeham would have preferred a brisker pace, but now that the chain of lord chancellor no longer weighed down his neck, he did not push his men, for they, too, as his household, had lost stature this past year. It was not as fine to be the household officers of the bishop of Winchester as it had been to be the officers of the lord chancellor of the realm. Wykeham wanted them content. His enemies would be only too happy to make alliances with his staff.

He had used the time to pick at his wounded dignity. God knew he could have found better occupation for his hours in the saddle, but he was weak, too proud; he knew that of himself.

Their small wagon had creaked and groaned over the ruts in the road, its cargo the heart of a York knight who had gone in his dotage to France as a spy and had been caught and imprisoned, dying there while Wykeham was negotiating his ransom. The Pagnell family were making much of what they considered Wykeham’s failure, though he was of the opinion that Sir Ranulf Pagnell had simply been a foolish old man. However, as the family were influential in Lancastrian circles, Wykeham had tried to appease them by escorting Sir Ranulf’s remains to York, the heart that he had coaxed from the French king with his own money. The Pagnells did not think even this sufficient retribution. For all his efforts, Wykeham was not to preside at the knight’s requiem. Indeed, he had not even been invited to attend.

As Wykeham sat in the archbishop’s garden miserable in his self-pity, a shadow fell across him and the scent of lavender drew him from his thoughts. He squinted up, his eyes watering in the light. Brother Michaelo, the archbishop’s elegant secretary, stood before him.

Wykeham assumed the monk had come to deliver a message. “What news from Lady Pagnell?”

Michaelo bowed his head slightly. “The lady sends her apologies, but she cannot meet with you until her departed husband’s month’s mind.”

Wykeham bristled. “How can there be a one-month Mass for Sir Ranulf when we know not the date of his death?”

“She means a month from his burial, My Lord Bishop, a month from tomorrow."

Lady Pagnell and her son and heir, Stephen, were being guided in this shunning of him by their Lancastrian friends, Wykeham was sure of it. But to press her would merely inspire accusations of cruelty to the widow in her mourning. He could ill afford to make himself more unpopular in the city than he already was.

Brother Michaelo held up to him a glass vial. “If I might suggest, My Lord Bishop, a soothing wash for your eyes? This is from Captain Archer’s wife. She is as skilled as any apothecary you might have in Winchester.”

Wykeham grunted. “I am in your debt. Take it to my servant. I shall try it later.”

“I could assist you in applying a few drops now, My Lord Bishop.”

And make him look a fool, with the liquid staining his face, his silk clothing. “To my servant, Brother Michaelo.”

The monk bowed and withdrew.

Wykeham fell back into his dudgeon. Ungrateful family, the Pagnells. But they would see; he would not idle away the rest of his life waiting on the likes of Lady Pagnell. The king would have him back.

He shaded his eyes and gazed upon the great minster across the garden. A building project would be to his liking right now. As he rode north he had thought about the ruined church of All Saints in Laughton-en-le-Morthen. Though it was no longer his prebend, he meant to rebuild it. He rose with a thought to observe the work on the minster lady chapel, a better occupation than wallowing in self-pity.

Wishing to be truly free for a little while, Wykeham watched the household guards for a chance to depart unescorted. He felt like a truant schoolboy as he hurried through the gate and toward the minster. Winded and silently laughing at his foolishness, he almost forgot the grit in his eyes, but soon the burning began anew. He caught his breath and dabbed at his eyes, determined to enjoy this moment alone.

To his left the south side of the minster nave soared above him; to his right

St Michael-le-Belfrey cast a late-afternoon shadow. As he rounded the south transept his view of the construction was blocked by a huge mound of stones and tiles butted up against what had been the far southeast corner of the minster before work on the lady chapel began. The church of St Mary-ad-Valvas had been dismantled to create room for the construction, and the stones and tiles were being reused, though much of them merely for rubble within the walls. Skirting the mound, Wykeham saw two men chiseling stones in the masons’ lodge. As he considered whether to interrupt their work a shout startled him.

“My lord, drop down and cover your head!”

He did as he was told, and just in time. A heavy clay tile thudded onto the path a hand’s breadth short of him, cracking on impact. He curled into himself so tightly he had difficulty breathing. But he would not lift his head, he dared not. He did not mean to play St. Thomas Becket to the duke of Lancaster’s Henry II. He would not be so easily murdered.

1

THE BISHOP’S TROUBLES

Owen Archer crouched beside the unmoving figure. “My lord, are you injured?” As he searched for a pulse the bishop stirred beneath him.

Slowly Wykeham raised his head. “Archer. I do not think I am injured.” He was very pale and his breathing shallow.

By now masons and soldiers crowded round the kneeling pair, and Alain, one of the bishop’s clerks, assisted Owen in helping Wykeham to his feet.

“My lord—” Alain shook debris from his master’s robes.

Once on his feet Wykeham held himself erect. “I must remove myself from the danger,” he said, stumbling as he stepped away from Alain.

The clerk caught his arm. Excellent reflexes for a man who looked to Owen a pampered noble. The crowd parted for Wykeham and Alain. Owen followed close behind.

Halfway through the palace garden the bishop’s other clerk accosted Owen.

“Your men were to guard Bishop William,” Guy said, shielding his eyes and squinting at Owen. He had the ruined sight and stained fingers of a scholar.

“Your master has much experience on building sites,” Owen said. “He knows they are unsafe, that he must have a care.”

“Are you calling him careless?” Guy demanded.

One of Thoresby’s servants saved Owen, summoning him to the archbishop’s parlor.

“I shall see to Bishop William,” Brother Michaelo assured him.

As Owen entered Thoresby’s parlor the aging archbishop reached down to a fist-sized clump of something on the table before him and poked idly at it, making it flake and finally crumble.

“Your Grace,” Owen said.

Thoresby did not look up. “Crushed stone,” he said. “Better than a crushed skull, that is what you are thinking.” Now the archbishop raised his head, fixed his deep-set eyes on Owen. “But you must do much better than that, Archer. Wykeham’s enemies must not find him easy prey while he is a guest in my household.” Aged he might be, but when Thoresby spoke in such a quiet voice it raised the hackles on Owen’s neck as it always had.

“It might have been an accident, Your Grace.”

“He must not have accidents while here.”

“He would have been safe had he not slipped away.”

“It is your duty to ensure his safety with or without his cooperation.”

A curse rose in Owen’s throat, but he swallowed it back.

“How did this happen,

Archer?”

“He chafes at such close guard, Your Grace.”

“Chafes,” Thoresby growled, turning away. “Has there ever lived a being more dangerous to himself than this obstinate and contradictory bishop? He swallows his pride to appease friends of Lancaster, but rides openly across the country to prove he is not afraid of the duke, belatedly worries about his safety and demands a constant guard, then escapes his guard to prove—what? Damn him.” The archbishop turned back, his bony face twisted in temper. “He won’t be caught here in York, Archer, I won’t have it!” He pounded the table, flattening the pile of crushed stone.

Owen knew his best defense was silence.

Thoresby pressed his temples and muttered a prayer, composing himself. “Perhaps he realizes he has overestimated his importance to Lancaster.”

Owen judged it safe to speak. “I do wonder about this issue with the duke. He is sailing home with his new wife, aye, and will be closer to Wykeham than he has been in a long while. But he comes to plot his acquisition of the crown of Castile and León, does he not?” Lancaster had recently wed Constance, the daughter of the late King Pedro of Castile. “He has far more important things to consider than his irritation with the bishop.”

“Lancaster’s net is wide, his coffers deep, and the number of his retainers greater than that of any man in the realm save his father the king. Wykeham is right to fear him. But I do not understand this chafing you speak of. He asked for my protection. Indeed, he asked for you by name. Have you offended him, Archer?”

“If I have, I know not how.” Owen did not like the way Thoresby was studying him.

“He has asked many questions about your time in Wales. You were working for Lancaster—I’d forgotten that.”

“On your orders, Your Grace.” Owen did not believe Thoresby had forgotten that. He had recommended Owen to the duke. Owen had not gone willingly. The inducement had been the opportunity to accompany his father-in-law, Sir Robert, on a pilgrimage to the holy city of St. David’s, fulfilling a dream that Owen could not deny the elderly man. Owen’s assistance had been Thoresby’s gift to Lancaster to ensure his

continuing favor now that Thoresby and the king were at odds.

“You returned long after the work for which Lancaster said he needed you had been completed,” Thoresby’s expression grew cold. “Perhaps Wykeham knows something I do not, is that it? I did not ask enough questions about that time? Did Lancaster give you any instructions to which I was not privy?”

This was a twist Owen had not anticipated, that Wykeham might mistrust his Lancastrian connections. He prayed Thoresby could not see the twitching of his blind eye beneath the patch. “He did not speak of the bishop of Winchester.”

“Anything.”

“He spoke only of the missions you know of.” It was ludicrous for Thoresby to question Owen so. “I chose to serve you rather than the duke of Lancaster.”

“That was many years ago. A man can change his mind. What did you do in St. David’s?”

“Your Grace, you know that I remained on the orders of the archdeacon of St. David’s.”

“I know some of the tale, but I do not believe I know all.”

And Owen did not wish him to know more. For in Wales Owen had been indiscreet—to the point of treason. But it had to do with the desire of his Welsh countrymen to thrust off the yoke of England, not with Lancaster’s machinations. It was quite possible that Wykeham knew of Owen’s flirtation with treason, having been lord chancellor at the time. Owen had thought himself safe. It was more than a year ago that he had returned, and in that time no one had confronted him about it. Perhaps there had simply been no need to use the information until now.

“Perhaps I should question Brother Michaelo,” Thoresby said. His secretary, Michaelo, had accompanied Owen to Wales, though he had returned to York before Owen was delayed in St. David’s.

It was plain Owen must humble himself, not give Thoresby cause to probe. “I’ll speak to my men, Your Grace, impress upon them the importance of the bishop’s safety.”

Thoresby lowered himself down into his cushioned chair. “Good.” He pushed the crumbled stone aside. “How is your wife?”

“She has regained much of her strength, Your Grace.”

“I keep her and all your family in my prayers,” Thoresby said in a quiet voice that held no

threats.

Crouching atop the masons’ scaffolding, Owen Archer looked down on the pile of stones and tiles stacked in the south yard of York Minster, more than thrice a man’s height. He was looking for signs that someone had climbed the mound and waited for the bishop of Winchester to walk past two days earlier. But it was no good—Owen needed to get closer. Holding on to the scaffolding with one hand, he stepped down onto the pile and balanced there, testing its stability. A few tiles moved, but he was able to find a reasonably firm footing. Slowly shifting his weight, he lowered himself into a crouch on the stones and tiles.

“I cannot see you now, Captain,” shouted Luke, a mason who stood below.

So someone could have hidden up here, out of sight of the bishop as he walked by.

“Now back up toward the south transept,” Owen shouted.

Shortly, Luke came into view. “I see you now.”

On hands and knees, Owen pressed lower.

“Gone now.” The mason laughed self-consciously.

Grabbing a tile, Owen crawled forward with an uneven motion. “Now walk toward the chapel again,” he called.

The mason soon reappeared, and Owen rose a little and tossed the tile, then flattened again. He felt the pile shift beneath him, but kept his head down.

“Just missed, Captain, and I do not think I would have seen you if I had not known to look.”

Owen sniffed, rolled over onto his side, eased up on his knees. Unless his sense of smell had weakened with his easy life, it was human urine he smelled. A long watch challenged a man’s bladder. Someone might have lain in wait here, though he would have risked being seen. As Owen crawled back toward the scaffolding he was visible to several of the masons at work on the chapel. Surely they would have noted an intruder in such an unusual place. They claimed they had been working on a different wall that day, farther down, but the supposed attacker

could not have foreseen that. Most baffling was the question of how the person had hoped to predict precisely when Wykeham would wander toward the masons. With his well-known passion for building it was inevitable the bishop would frequent the site while he was staying at the archbishop’s palace next door, but someone would have needed to lurk on the stack indefinitely. Owen thought it unlikely.

“I am coming down,” he called.

Once more on the scaffolding he had a view of the city, the Ouse Valley, the Forest of Galtres. He looked away and climbed down. In his youth such heights had not bothered Owen, but since losing the sight in his left eye he did not trust his judgment of just where the edge lay, doubting what he thought he saw, unsure of his balance.

Some placed the blame for what had happened to Wykeham at the feet of Sir Ranulf’s family. Owen could not believe they were involved. Proud they were, and angry about what had befallen Sir Ranulf, but surely they would not stoop to such depths to seek vengeance. Wykeham himself suspected John of Gaunt, the duke of Lancaster. With the king in his dotage and Prince Edward an invalid, the king’s second living son was eager to establish his power, and weaning the king from Wykeham was rumored to be a high priority. But Owen could not imagine the duke behind such an act, either. In fact, he thought the incident had probably been an accident, with no one but a careless worker to blame for it.

Luke was waiting at the foot of the scaffolding. “I heard you moving around up there. But I do not suppose the bishop would have made note of such noises. He would have thought it was one of us.”

“You stand by your statement that you saw no one lurking about?”

Luke stiffened. “Why should I lie, Captain?”

“Why indeed.” Owen silently noted that the mason had answered a question with a question.

Luke reached up—Owen was taller than most men—and touched the beard that followed Owen’s jawline. “Your hair’s so dark, the stone dust shows. It’s on your curly pate as well.”

Brushing dust from his hair, Owen thanked the mason for his assistance and headed for the minster gate. He suspected the mason was holding something

back, perhaps the clumsiness of a fellow worker, but Owen had wasted enough of this fine day. There was much to do in the apothecary garden before the first frost, and he did not want Lucie to grow impatient and see to it herself. She was still weak. Bending still sometimes made her dizzy.

Just before Lammas day Lucie had fallen from a stool while replacing a large jar on a shelf in her apothecary. The jar had badly bruised her left hand and cut her arm as it shattered. But far worse, she had lost the child who would have been born a few months hence. She had bled much during and after the accident, particularly when she lost the child, and her strength had been slow in returning despite Magda Digby’s tisanes of watercress, nettle and beetroot, and her Aunt Phillippa’s additional concoctions of eggs and cabbage. The physicks could not restore her spirit.

For days Lucie lay in bed whispering prayers of contrition. Cisotta, the young midwife who had attended Lucie in those first days, had assured Owen that women often behaved so after losing a child, some even after having a healthy baby. But when Magda Digby had returned from a birthing in the country and took over Lucie’s care, Owen could see her concern.

Long after they had closed the account books Lucie and Owen lingered at the table in the hall in the pool of lamplight. Jasper, Lucie’s apprentice and their adopted son, had gone to see a friend, and Phillippa and the children were in bed. Such a quiet moment seemed rare to Owen these days. Lucie did not seem to welcome idleness, but sought activity until she dropped onto the bed, exhausted. He knew she did not wish to think of the child they had lost. Even now her hands were not idle; she was tying mint sprigs together, her long, slender fingers moving quickly. The ghost of a smile touched her lips—in fact, her pretty face was alight with a calm contentment. She

loved her garden almost as much as her first husband had, found in working with the plants a peace much as Owen’s mother had so long ago in Wales. He wished Lucie might have known his mother—they had much in common, a gift for healing, for knowing the right combination of herbs and roots for a person’s ailments. His mother would have liked the level regard with which Lucie viewed the world—though of late there was a darkness in her gaze.

Tonight Owen noted deep blue shadows beneath her eyes. “You should have left the mint harvest to me,” he said.

“I took joy in it.” She lifted one of the sprigs, held it close so he could smell it. “A few more days and it would be too late. Perhaps if Wykeham forgets about his mishap the other day you can help me with some of the other autumn chores.”

“I am afraid he means to keep me occupied.”

“I am sorry for that.” As Lucie reached for another clump of mint she winced, withdrew her hand, and pressed the other to her shoulder.

“It is painful?”

“It aches, yes, but lying abed will not mend it.” She shook her head at him. “And your worry weakens me.” She had made this argument before. “You think—she fell once, she shall fall again. You think the accident has changed me forever.”

He did not know how to answer this. It was true and not true. He knew now that it could happen. “I meant nothing but that I had promised to harvest the mint. Guarding the bishop of Winchester put it out of my mind. He wishes to ride to his former parish of Laughton. He means to rebuild the church.”

“Where is that?”

“At the south end of the shire. Near Sheffield.” Several days’ ride, he guessed.

“He wishes to go soon?”

“Aye. He had thought to

to leave it until his business with the Pagnells was concluded. But Lady Pagnell refuses to see him yet. The journey would fill the time.”

“Poor Emma. Her mother’s presence is making everyone in her household ill at ease.”

“She is a difficult woman?” He had met Lady Pagnell only at formal events.

“Yes, both she and her steward are intrusive guests. Emma came today, asking for a sleep potion for herself. I shall make up something to soothe her—Jasper!”

Their 14-year-old adopted son had come rushing in, panting and flushed from a good run, skidding to a halt by the table. Lucie steadied the pile of books as he dropped his hands onto the table, leaning, catching his breath. He raked his pale hair back from his face with an impatient gesture. “There is a fire in Petergate. The house of the bishop of Winchester.”

“God have mercy.” Owen got to his feet. So did Lucie. He leaned across the table, took her hand. “Stay within, eh? One of us heading into danger is enough.”

She shook her head. “I can help those who breathe too much smoke. Passing ’round a soothing drink is not dangerous.”

He did not like it, but he saw she was determined. “Aye, you are right.” He grabbed a cloth from a basket of laundry by the door to the kitchen, thinking he might need something to protect his nose and mouth from smoke, then headed for the door.

2

A FIRE IN PETERGATE

Smoke already masked the October smells when Owen stepped out into St. Helen’s Square. Shouts drifted down from the scene. Owen looked up, expecting to see the glow of fire in the sky above Petergate. But the sky was a deep blue, the stars silvery white. Perhaps God was with them and the fire had been caught early. People ran past him. By the time Owen reached the top of Stonegate several chains of folk stretched along Petergate passing buckets of water from the nearest wells. A boy clutching an empty bucket emerged from the smoke near the burning house and headed down one of the lines. Another followed close behind.

Owen stopped him. “Where is the fire? I see no flames.”

“The fire is down below, in the undercroft, Captain. They pulled out a servant—his clothes ablaze. They doused him with water and rolled him in the dirt. The other is dead, they say. A maidservant.”

Owen let him go, hurried on. The street was already slippery with spilled water. As he moved closer the vision in his one good eye blurred with the smoke that belched from the undercroft doorway. The walls of the undercroft were stone, as was the roof tile, but the support posts and the story above were of timber. Near the door stood Godwin Fitzbaldric, the bishop’s new tenant, here in York only a few months. He was calling out orders, hurrying the bucket wielders along. His face was streaked with soot, his shirt torn. He was a tall man, leaning toward fleshiness, almost bald but for a dusting of dull red hair running from temple to temple across the back of his head.

“Is everyone out of the house?” Owen asked him.

Fitzbaldric drew an arm across his broad brow. His wide sleeve was heavy with water and torn, the tight sleeve of the shift beneath soiled. “They pulled two of my servants from the undercroft. They were alone in the house.”

“You were not at home when it began?”

“No. We dined at a neighbor’s.”

“Did you ask the injured servant whether any others were in the house?”

“He is past speaking.”

“Not dead?”

“Not yet, but how he can survive with such burns--”

“Has anyone searched the upper story?”

Fitzbaldric shook his head. “They were—”

Owen did not wait to hear the man’s repeated assurance. Anyone in a crowded city knew to search a house on fire. Servants had friends; neighbors might be visiting. Having moved from a village near Hull a few months ago, perhaps Fitzbaldric did not understand that—fires were a regular occurrence here. Owen pushed past the human chain passing buckets, dipping the cloth he carried into one of the pails of water. Tying the wet cloth over his nose and mouth, he mounted the stairs, which were shielded so far from the flames by the stone wall of the undercroft. Pushing open the door, he shouted, “Is anyone here?” Stepping within, he found the crackle of fire and the shouts of the people muted. His voice echoed loud in the hall as he called again. Smoke seeped up through the floorboards; a flame licked

over in the front corner. Two lamps were alight on the trestle table, and a lantern on a wall sconce. Already their flames were blurred behind the smoke in the air.

Something clattered up in the solar at the far end of the hall. As he rushed toward the steps his eye watered from the smoke coming up from below. “Come down! The undercroft is ablaze!”

A foot appeared on the steps, then a second. So much for Fitzbaldric’s stubborn certainty. It was a woman, her skirts hitched up to descend. She moved slowly, looking about her as if confused. Her cap was askew, her dark hair tumbling down her back.

“Poins?” The woman’s voice trembled.

“Hurry. This is too much smoke for anyone to breathe.”

Seeming only now to focus on him, she crouched down on the steps and reached toward his outstretched arms as if she thought to take his hand, but she was now so unbalanced that she lost her footing and slipped down the last few steps, landing in Owen’s arms. She had fainted.

He pulled her away from the steps, crouched, lifted her up, and hoisted her over his shoulder as he rose. His back would wreak vengeance for that on the morrow. Pray God he lived to suffer it. He blinked against the smoke, took a step forward, checked himself. The smoke was obscuring his vision. He cursed the Breton woman who had cost him the sight in his left eye. Trying to establish the angle at which he had approached the steps to the solar, he prayed he was headed in the right

direction. The cloth over his mouth and nose had dried in the heat. The smoke burned deep in his chest. He felt from the vibration of the floorboards someone striding toward him.

Alfred, his second in command, materialized. “This way, Captain.”

Out on the porch Owen crouched down and slid the woman from his shoulder. He did not trust himself to bear his own weight and hers down the stairs, not with his lungs on fire. He ripped the cloth from his face and gasped the cool air.

Alfred took up the woman. “Mistress Wilton awaits you below, Captain. She has been passing ’round a syrup for our raw throats.”

Fitzbaldric met them halfway up the steps. He lifted the woman’s head. “But this is May, my maidservant. I thought…. What was she doing up there?”

Owen wiped his face. “Sleeping, from the look of her. Turn ’round, the steps will catch anytime.” Alfred had already continued down, keeping well to the outside edge. Nearer the house, the steps were catching sparks from the upper story.

Fitzbaldric turned, shouted, “Wet the steps!”

One of the human chains shifted direction.

Lucie awaited Owen on the ground, standing still in the roiling sea of people, too close to the fire for his liking. When he reached her, she embraced him, hugging him tightly, then stepped back, plucked off his cap, ran her fingers through his hair, took up his hands and examined them. “Thank God you are unharmed.”

“I did nothing foolhardy.” He gladly accepted the flask she offered. “Did you see where Godwin Fitzbaldric headed?”

“Across the way. Come.” Lucie guided him through the crowd passing buckets, shouting, away from the house, the smoke, the sound of cracking timbers.

The Fitzbaldrics stood beneath the overhang across the way, watching Alfred. With the maid in his arms, he was following Robert Dale and his wife, Julia, to their house at the corner of Stonegate and Petergate.

Lucie had paused in a pool of torchlight set in the wall of one of the houses opposite the bishop’s, far enough from the Fitzbaldrics that they would not be able to hear her. “The Dales hosted a banquet to introduce the Fitzbaldrics to some of their acquaintances this evening,” she said. “Now they have offered the couple a bed for as long as they need, as well as the maid and cook.”

“You have spoken to them?”

“A little.”

“What of the injured manservant?”

Lucie did not answer at once. She watched not Owen but the mass of people working on

the fire.

Owen touched her arm. “Lucie?” He had come to dread her silences.

She pressed his hand, a gesture she had made seldom of late. “They might yet save the upper floors. Listen. It is quieter now.”

It was difficult for him to block out the sound of the people, but gradually he was able to hear what she did—the fire hissed rather than roared. Yet he remembered the burning corner in the hall. “I do not think we can hope for that.”

Still facing the burning house, she said, “I told them to take the manservant to our home.”

He had forgotten his question and did not at first grasp what she was saying.

Lucie turned to him. “Owen?”

Her meaning dawned on him. “We cannot care for him. You are yet weak—”

“It is done. He is on his way, and Magda Digby with him.”

In the torchlight Owen could see the set of Lucie’s jaw, the challenge in her eyes, and against all reason he was glad of it, for he had not seen that spirit in her for a month. “So be it.”

She pressed his arm. “Come home?”

“Not yet. I want to see the dead woman.” He shook his head at her. “Why would you do this? You don’t know these people.”

“Why did you go in search of the maid?”

The Fitzbaldrics were looking their way. It was not the time for an argument.

“We have been noted,” Owen said. “I would talk to them. Your flask is empty now.” He handed it back to her. “Go home. I’ll follow when I can.”

“We are most grateful to you, Captain,” said Fitzbaldric as they drew near. “God help me, but I was certain the house was empty.” He did not look Owen in

the eye.

“We could not know she was up there,” said his wife.

Owen was not interested in their excuses. “Have you seen the woman found in the undercroft?”

“I did,” said Fitzbaldric, “when they carried her out.”

“You had identified her as your maid. Does she look like her?”

“Have you see the body, Captain? I could tell little else than that it was a woman. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...