In the dark, I am alone with my body.

I run my fingers over its flesh, drawing out warmth like a tiny sun behind these cold stone walls.

If I close my eyes, it’s your hand there, sure of itself, as I could never be.

Here are my lips.

Your fingers slip between them, quick, like moths, searching for a light only you can find.

Here is my thigh.

Soft, you say. Like the skin of an apple. You make a wolf face, as if you’ll bite.

The curve, just here, of my hip bone, knife-sharp. I press myself against you and watch a bruise bloom, blue and purple and lovely.

The water crashes beside us as you spread out my blanket, its wool rough against our skin. The air smells of lightning.

When you pull off my dress, I shudder. Your voice is a storm that I can’t keep from coming. My body shakes with its thunder.

You trace my face, my neck, my heart.

And then it is my hand again, hovering over this lonely, pulsing patch of skin.

In the tomb of these walls, where all I can smell is the stink of others’ flesh, somehow it is still beating.

They say I am never to leave here until I’m hanged.

In the bed beside me a woman screams.

I scream too.

Because no one will ever love me like that again.

I’m only seventeen, and I’ve killed a man . . .

1

The dead do not always keep their secrets.

Sometimes the living must do it for them.

Tucking the knife into her pocket, Molly Green climbed down into the grave.

The river had slipped inside the dead girl like a rotten kiss, swelling her skin until it split. Her once-beautiful raven hair was tangled and clotted with mud, and a rancid smell rose from the body like potted meat left in the sun.

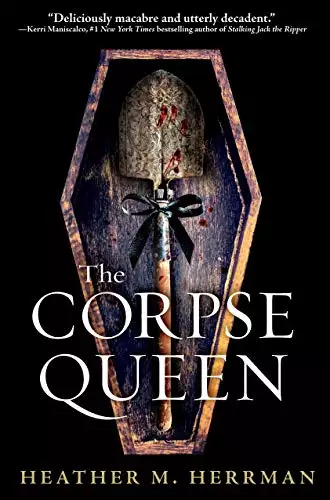

What she was about to do made her think of the horrible stories the nuns told. About a queen of corpses in Philadelphia.

“Oh, Kitty,” she whispered.

Struggling to stay calm, she wrapped her arms around her friend and lifted.

From above, the moon’s fading glow turned Molly’s red hair to flames.

Kitty’s corpse peeled up reluctantly from the ground, like dough scraped too soon from a pan. Parts of her seemed to want to stay stuck forever in the frozen February earth, and the harder Molly wrenched, the more she felt she would break her.

“Damn it,” Molly whispered. “Let me help you!”

There was a terrible second when she was sure Kitty’s limbs would simply pull apart like a bug’s legs caught in flypaper, but then she yanked harder and the body tumbled free.

Molly lay there, gasping, Kitty’s dead body on top of her, the weight unbearably heavy on her heart.

Overhead, a grease moth circled lazily, then landed, seeking to feed. Molly felt its tiny, delicate feet skitter across her skin.

In that instant, she wanted nothing more than to give up. To scream until the nuns found her, and then maybe she could die too. They’d put her in an asylum, and she could stay there for the rest of her days, screaming with the other madwomen, pulling out her hair and banging her head on stone walls, where at least then she could be free from the constant disappointment of others.

No.

It’s Kitty, she reminded herself. Kitty, whom you love. Kitty, who could not make a corner on a bed, who laughed like a bird and sang like a tiger. Kitty. Your Kitty.

The stink was nearly unbearable now, but there was something sweetly familiar in the rot, a scent that made her think of Christmas.

She and Kitty had stolen an entire ham from the nuns’ last feast day, and no one had ever been the wiser.

“The trick,” said Kitty, “is to commit your sins in plain sight.”

And that was what they’d done, carrying the tray between them out the side door of the orphanage, as brave as you please. A passing priest had even offered them the sign of the cross.

They had not been able to stop laughing, the two of them triumphantly devouring their spoils, hidden high up in an old oak tree like giddy crows. Licking the slick of peppermint-and-clove glaze from their frozen fingers.

Now, using her knife, she reached around Kitty and began to cut away what was left of the ruined dress. The blade slipped, its rusty metal dull from too many kitchen washings, slicing jaggedly into her palm. She felt blood welling to the surface but did not stop.

The dress fell away. Molly ran her fingers up the icy skin, searching.

She had seen it only once—a small pink piece of flesh, no bigger than a finger.

She and Kitty had been swimming in the river, the sunlight dancing between them. Its rays caught a jeweled drop of water on the wiggling nub just below the small of Kitty’s back.

But as quickly as the strange limb had appeared, Kitty had submerged it. “The priest says anomalies of the flesh are a punishment,” she whispered.

Molly should have turned away. Refused to involve herself in the lives of another orphan, as she always had before she met Kitty. Instead, she said, “The priest is a great fat fucking liar.”

The words hung between them like a dare.

Then Kitty laughed, and everything changed.

In that moment, they became more than just two orphans—they became bound. Sisters.

“No one else can ever know.” Kitty’s face grew serious. “Please, Molly. They’ll never let me be just a girl again. I’ll be a sermon or . . . or . . . a freak.”

“I swear it,” Molly had promised.

From afar came the sound of approaching voices. The nuns, finally come to clean the body.

They should have done it back at the church, as they did for all the other dead. Molly had waited all night, hiding herself in the priest’s confession closet after she’d heard they’d dragged her missing friend’s body from the river.

But the body had never arrived, and in the last hours before daybreak, not knowing what else to do, she had come here, had watched as the new gardener pulled Kitty’s body from his shed and tossed it like trash into the hole. The man was a Swedish Protestant and had either not been told to leave the body in the church or, with his limited English, had simply misunderstood.

The nuns’ voices drew closer.

“Hurry up, Mary Margaret. That fool gardener’s already put her in the ground. Someone find him and have him dig her out.”

When they cleaned Kitty, they’d see the tail, and then Molly knew what would happen—like a brood of clucking hens, they’d bring the juicy worm of a story to Mother Superior.

Kitty would no longer just be a girl; she’d be a girl who had sinned.

A girl who had done something so terrible that God had punished her with a disfigurement before she was even born. They’d say she’d deserved it. They’d say, probably, that she deserved to be dead too. And they wouldn’t say it silently. They’d let the priest preach it from his pulpit, spread Kitty’s name like an infection to the other orphan girls, along with all the other doomed women he railed against each Sunday.

The moon’s cool glow grew pink, eclipsed by the rising sun. Molly lifted her face to its bloody light.

Grabbing Kitty’s lifeless hand, she held it a final time. Mother Superior was wrong. Kitty would never have left her willingly.

I’ll find who did this to you, Kitty, I swear it. And when I do . . .

She felt the rage rise like a wave in her breast but quickly tamped it down.

She had but minutes. Seconds, maybe. The nuns might not give Kitty’s stained soul the burial it deserved, but they would not besmirch God by sending filthy flesh to his judgment table.

With all her strength, Molly crawled from beneath the waterlogged body.

She had failed Kitty once. She would not fail her again.

Standing above the corpse, she raised the knife . . .

But the tail was already gone.

“Crawling into a coffin?”

Molly followed Mother Superior into her office. She’d been pulled from predawn prayers, and a rosary dangled like a whip from her hand. Everything in the room spoke of punishment: hard wooden benches and crosses nailed like promises along the wall. The door slapped closed behind them.

Molly fingered the knife in her pocket. She’d managed to hide it, but the nuns had found her before she could crawl out of the grave. They’d brought her immediately here, a place that she knew all too well.

Only a bright-blue candy dish perched on the nun’s desk brought any color to the stark neutrals of the room. Molly stared at the dish hatefully. Mother Superior kept it there, full of candy, so that the unfortunate orphans brought to her might see the sweets they were being denied.

“Well, Miss Green, what do you have to say for yourself?”

Even with the cloying incense that permeated the room, Molly could still smell the stink of the hole. It clung to her like an unwanted lover.

“Kitty didn’t have a coffin.”

“Suicides aren’t rewarded with luxuries.” The nun’s wrinkled face hardened. “Your friend made her own choices.”

“She didn’t kill herself.”

“I know it’s hard to accept.”

“It’s not hard to accept.” Molly spit the word. “Kitty didn’t do it. She was a good Christian. A good Catholic.”

“Good Catholics don’t throw themselves into the river,” Mother Superior said in a low voice.

There was the smallest flicker in her eyes, and Molly understood suddenly that the woman was enjoying herself. Enjoying the power of her judgment. “Your friend ran away, and I’ve no doubt you helped her do it. Ugly girls are always helping their pretty friends get into trouble. Now you must both suffer the consequences.”

Angry, Molly felt blood rush to her ears, and it was as if she, not Kitty, were drowning. “That’s not what happened!”

Mother Superior sat primly at her desk, steepling her hands beneath her chin. She did not invite Molly to sit. “Then tell me what exactly did.”

There it was, the question that Molly could not answer.

Closing her eyes, she saw it again. The bright-red line where the tail should have been, the wound neatly, perfectly cut. “I don’t know.”

“Then let me tell you.” The nun’s voice had grown misleadingly tender, her words a slick caress. “Your friend met a boy, and he led her to sin.”

Molly’s mouth gaped.

“Did you think I didn’t know?” Mother Superior’s white teeth flashed triumphantly. “Your friend was running about like a common whore.”

“No,” Molly protested. “They were in love! I didn’t like it either, but he was well-off. A doctor. They were going to be married.”

Mother Superior laughed, then stood. “Why would a wealthy man marry a girl in your friend’s condition?”

Molly stiffened. “What do you mean?”

A surprised smile cut across the nun’s face. “You didn’t know? Kitty Wells was pregnant.”

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved