Rowan clutched his shortspear and approached the Thulu Jungle. The dense, tropical wilds teemed with echoing bird calls and low, guttural growls. The air, wet and heavy, thrummed with swarms of buzzing insects. Thick and slitted shadows darkened the emerald ferns masking the ground. Life in strange abundance dwelt therein, and Rowan was about to stalk it.

His blood pulsed with the thrill.

Naja, his guardian-mother, strode alongside Rowan garbed in a short, sleeveless dress made from her latest kill—the creamy hide of a twin-tail panther. She circled him, fingering the black pearl necklace hanging above her shapely bosom.

“Lower your heart rate,” Naja instructed, easing her palm over Rowan’s tanned, leather breastplate. “I know you’re anxious to begin, but slow it down. You don’t want the twin-tail detecting your racing heart.”

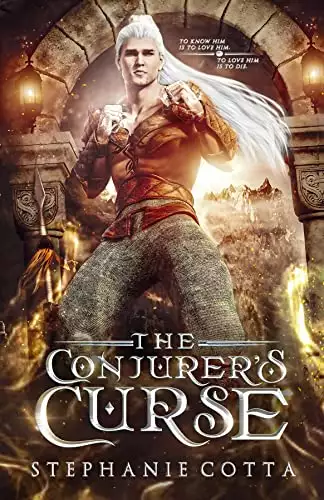

Rowan exhaled a calming breath, steadying his pulsating heartbeats and relaxing his taut muscles. The balmy breeze swept his long, ivory hair over his stark-white face. Naja snatched the loose strands between her nimble fingers and gathered them behind his neck.

“Remember what I’ve taught you,” Naja said, weaving Rowan’s hair into a warrior’s braid, “and you’ll pass the trial.”

The Moran’ysi njahi. The warrior trial to vanquish his first twin-tail panther on his own. Three years of training and preparation came down to this pivotal feat. He could not fail—not if he wanted to earn the validation of the villagers in Karahvel.

Rowan fidgeted with his leather bracers, fixating on the jungle’s shrouded vines jumbled like a clump of seaweed. “If I defeat the twin-tail, will the villagers finally stop calling me a dikyli?”

“We can hope,” Naja said, wistfulness stealing into her alto voice. Then her usual constructive tone reengaged. “But don’t focus on the villagers. Focus only on the twin-tail.”

Naja tied off Rowan’s braid, then faced him. “You’re ready for this,” she said, her own rows of coiled black hair swaying with her movements. She gripped him by the shoulders, her ebony face shadowed by the twisting tree limbs. “Stalk the twin-tail to its den and claim its hide. Hold to my instructions.”

Rowan nodded, slowing his breaths. “Set the bamboo spears, lure it out, and strike unseen,” he recited, cinching his grip around his shortspear.

“And remember, Rowan,” Naja said with a solemn stare, “still water, steady heart. See the beast as an equal, and be fearless in your strike.”

Rowan nodded, drew in a long breath, then entered the dense woodland, pushing past lofty palms with deft strides. Though lean in frame, Rowan prided himself in being nimble where it counted—his mind and body honed for this s

wift jungle chase.

A twin-tail could smell a hunter from afar, so when Rowan came upon the first mud pit, he coated his pale skin, masking his scent, and blended in with the shadows. He scoured the damp dirt at a measured pace, searching under the swath of leafy foliage for twin-tail tracks. Paw impressions were often hard to spot, but last night’s rain softened the soil, revealing a set of fresh tracks.

Rowan followed them, which led straight to a burrow obscured by a mass of twisting vines. The panther retreated there to feed. A trail of blood indicated an animal had been dragged through the tramped brush.

Rowan fashioned his traps. He stuck a dozen cloven bamboo reeds into the moist ground, angling each one upward like a thrusting spear. He circled them around the twin-tail’s den, leaving the creature with only two options: risk leaping over the sharp bamboo or seek escape over its burrow—where Rowan would stage his ambush.

Rowan grappled his way up a canopy tree’s spiraling vine to higher ground. From there, he dropped onto the mounded burrow, crouching low in the ferns wet with dew.

The disturbance to its home summoned the twin-tail. Its furry head poked out from the hole, and the creature spread its wiry, white whiskers. Rowan held his breath. The panther approached the circular row of bamboo reeds, belly low to the ground, dragging its two whiplike tails through the variegated ferns. It inspected the deadly barrier with several deep growls and swatted at the bamboo. The reeds wouldn’t come free with ease; Rowan had buried them well. The twin-tail then attempted to squeeze its body between the tightly arrayed bamboo, and that, too, failed. The creature scrambled backward, shaking its creamy head, whipping its tails in an agitated tangle.

It flicked its amber eyes, seeking a safer route, and turned about face. The creature stalked back toward the den, its gaze transfixed on the mound. The twin-tail chose the path Rowan wanted. He swallowed an anxious lump and lifted his shortspear, readying his stance.

The creature leapt upon the mound, and Rowan came face-to-face with his quarry. The twin-tail’s eyes dilated into black pools. Its blood-smeared jaw dropped open with a challenging snarl, and with claws spread, it sprang into an attack.

Rowan thrust his spear, striking the panther high in the chest. Its scream ricocheted through Rowan’s eardrums. The twin-tail crashed into him, raking its claws against his shoulders. Rowan hissed in pain, gritting his teeth. He squirmed beneath the thrashing beast and hurled kicks to its belly. His heartbeats thundered as he crammed the spearhead deeper. The twin-tail’s wild screams drawled into internal growls, losing spirit. Breaking free, Rowan pulled out the spearhead, and the twin-tail rolled off the mound, falling at the entrance to its den.

Rowan’s heart pounded in his ears as he peered over the mound’s rounded lip. The creature laid still. The blood-wound at its center seeped into the surrounding fur.

Burning skies, I beat it!

Hands shaky, Rowan rappelled to the ground and steadied his racing heart before his kill. The twin-tail was his equal in spirit. Vanquishing it signified he surpassed it in strength.

Naja arrived at the kill site, her shortspear strapped to her back. She shimmied between the bamboo stakes and embraced the muck-covered Rowan. “You did well.” Her dark lips curved into a proud smile. “Were you wounded in the fight?”

Rowan rolled his shoulders, wincing. “Only some grazes.”

Naja pulled away and regarded his trap. “I see you heeded my instruction and used the bamboo spears.”

“They worked exactly as you said.”

Naja lifted a hand to Rowan’s mud-caked face, and her smile broadened. “You need to wash off before we head back to the village. Otherwise, you might scare everyone.”

Rowan snickered. “Yeah, ’cause they’ve never seen a mud-covered albino before, huh?”

“They haven’t, Rowan.” Naja

laughed. “You might confuse their prejudices.”

“Then maybe I should encase myself in mud on a daily basis.”

“That’s one strategy. Though, they might start complaining about the smell.” Naja wagged a hand over her broad nose.

Rowan sniffed his armpits. “Is it that bad?”

“Like a twin-tail, I could smell you from a distance.”

“That’s a joke, isn’t it?”

Naja flashed a wry smile. “Head for the waterfall and wash,” she instructed, prodding him forward. “I’ll make a sling for us to carry your kill. It won’t take me long, so no dawdling.”

Rowan soon reached his favorite waterfall, cascading into a wide, glistening pool. He shuffled behind the underlying cliff face and into the deafening downpour. The plastered mud peeled away, and he was back to his alabaster, painted self. His red eyes flooded as he tilted his head back, rinsing out his hair. No one else in the village shared his peculiar features, his oddities—the crescent-shaped birthmark on his neck the most unusual of all—and the villagers never let him forget it.

After the rinse, he returned to Naja, and together, they hefted the twin-tail back to Karahvel. People gathered around the outskirts of the coastal village. Chieftain Haraz stood with drooped shoulders at the forefront, distinguishable by his ceremonial headdress boasting bright feathers and ivory adornments. The elders who comprised the majiri—Karahvel’s governing council—clustered around the chieftain. Each wore long colorful tunics cinched at the waist with braided belts.

Like curious jungle birds, they came closer to inspect the kill, as was the custom when a youth successfully performed the Moran’ysi njahi. Haraz’s wrinkled face showed neither enthusiasm nor disapproval, but the majiri couldn’t mask their surprise. Rowan didn’t know if it stemmed more from his feat or from his lack of injuries.

Naja stood at attention before the chieftain and the majiri, her long arms and legs as taut as thick bamboo. “Rowan has killed his first twin-tail,” she announced. “I, Naja, his guardian-mother, ask he be recognized among the Karahv

elans.”

Haraz turned to the elders, and with hushed voices, they deliberated their verdict. The majiri’s spokesman, Menka—a bald, older man with a mangled upper lip and a perennial scowl—stepped forward and addressed Naja. “The majiri will recognize the boy’s achievement. However, his status as a dikyli remains.”

Outsider.

Rowan hated that word. All his life, he heard it whispered as a reminder of how different he was from everyone in Karahvel.

“As such,” Menka continued, “he won’t be joining the ranks of the Karahvelans.”

Naja stabbed her spear tip into the sand. She thrust a judging finger at the elders. “You all know he’s earned his place. Or am I to understand you’re refusing to recognize my boy’s warrior status because he’s not like us?”

“He’s not your boy, Naja,” Menka shot back, quick and harsh as a viper’s strike. “Just because you refused to accept a husband, it doesn’t make that white leech your son.”

Rowan bristled at the insult.

Naja’s muscles bulged as if she’d been slapped. “I chose not to accept your son as husband—let’s be clear on that, Menka. A warrior’s life suits me better, as does instructing my boy. I thought it was our custom to rear any motherless child.” She shot a firm stare at Haraz. “It’s why I fought to have him placed in my charge, Chieftain. We don’t abandon children, for it would make us no better than lynasi.”

The implication wasn’t lost on Rowan. In the jungle, female lynasi were known for abandoning their young when endangered. In Karahvel, the rearing of children was one of their most sacred undertakings; neglecting a child was unthinkable.

“It is for that reason the boy still remains in our village,” Haraz said, his voice wooden.

“Yes, but what if this boy is the source of woes?” Menka persisted, leveling his finger at Rowan. “There are many who believe the dikyli is a plague.”

“Stop hiding behind that word,” Naja snapped, her tone matching her sharp glare. “Rowan has

lived amongst us for thirteen years. When will you accept him as one of our own?”

“With all the suspicion surrounding his origins, how can we?” an old, croaky-voiced elder said. “He was born under a red crescent moon! A fact we can’t ignore.”

“Nor the ominous mark on his neck,” a short elder interjected, squinting his dark, nebulous eyes.

“It‘s a bad omen,” Menka said, nodding along with his fellow elders. “The death of his first three guardian-mothers is a troubling phenomenon. Have you forgotten what happened to Sylda? Her skin aged beyond her twenty-five years!”

Rowan cringed, forced to hear every condemning word the elders uttered. The majiri was no different from everyone else in the village. They voiced their frank thoughts as if Rowan didn’t exist, unconcerned if he heard them or not. The overwhelming urge to retreat back into the jungle—far from these scornful stares—rooted in his mind.

Haraz remained conveniently quiet as the elders continued their railing. They respected Naja’s position as a warrior but held too many qualms to grant her wish.

“Be wary, Naja,” Menka warned. “If things continue as they are, you’re next to follow Sylda. You die, and we’ll all know what he really is—cursed.”

Naja turned away from the majiri in a huff. “Come, Rowan, back to our hut. These fools can stew in their superstitions. You and I are going to celebrate.”

Rowan ignored the animosity dripping from the elders’ scowls, lifted his chin high, and with Naja’s help, carried his kill toward their hut. Along the way, coalescing murmurs drowned out the quiet lull of the sea. Villagers halted their chores and eyed the slain twin-tail. They knew what it meant: He was a warrior.

Rowan and Naja reached their hut and worked together to prepare the animal. They divided the carcass, stripping away what they would use for ornamental items and clothing. Naja removed the organs; Rowan skinned the twin-tail’s hide. A nagging question pressed at his thoughts as he slid

his knife between the layer of animal skin and muscle. He couldn’t shake Naja’s argument with the majiri out of his mind—or Menka’s harsh words.

“Is Menka right about me?” Rowan bent his head, rubbing at his crescent-shaped birthmark. “Am I . . . cursed?”

“Ignore Menka,” Naja said with a sharp tsk, her dimpled chin tightly drawn. “It’s village superstition and not for you to worry about.”

Except Rowan did worry. He wasn’t ignorant of the villagers’ whispers—nor their harsh looks. As the village freak, he was blamed for every bad thing, and well, lately, he wondered if the majiri might be right. “But what Menka said about Sylda—it’s hard for me to ignore. How can I, after what happened to her?”

The frustrated fire in Naja’s eyes dissipated. “Her death was a tragedy, but you must understand something—when inexplicable things occur, people look to attach blame. And since the majiri insists on regarding you as a dikyli, it makes you the ideal target for their suspicions. So spare them no thought.”

Naja’s directness ended the topic. She disappeared into the hut and came back with a cowl hood, woven from multi-colored thread, draped over her arm. “This is for you.”

Rowan accepted the cowl and read the weavescript to himself: “In honor of your Moran’ysi njahi, may this cowl forever speak of my pride in your accomplishment. I see you as warrior and equal.”

Naja took it from Rowan’s hands and placed the cowl over his head. “The majiri may not count you as one of us, but in my eyes, you’ve earned your place among our warriors.” Pride glimmered through her onyx eyes, enlivening their dark luster with soft light.

Rowan basked in Naja’s love and praise. She instilled him with courage and skills he could rely upon in the face of danger. He couldn’t imagine life without his guardian-mother’s daily instruction...