Introduction

A.S. King

Here is an incomplete list of things one can collect: crystals, lies, math tests, kittens, scraps of paper with things written on them, books, antiques, enemies, punctuation, friends, rumors, cars, feelings, baseballs, stepmothers, trophies, knowledge, joys, earbuds, anger, office supplies, judgments, conquests, opinions, insults, prophecies, dryer lint.

Collections are everywhere in human culture. Humans collect a lot of things. But why? Why do we collect things? I woke up from a dream with this question one day in 2021, and it followed me around until I did something with it. I started with research, but then I had to trust my gut.

There is science here—a psychology of collecting that has been studied by industry and academia through the lenses of economics and marketing to anthropology to neuropsychology and social psychology. Science tells us that collecting is ubiquitous, usually harmless, and normal, not to mention profitable. It tells us that a majority of children are collectors, as well as about 40 percent of adults, and it draws lines between healthy collecting and hoarding and other concerning behaviors. When asked, Why do we collect things? the data give us many answers depending on what’s being collected, how it’s being collected and shared, and in what culture the collecting is taking place. It’s all very logical and tidy. But it doesn’t feel true. While science is awesome, it lacks the nuance of artistic meaning, and that’s part of why I think people collect things. I believe we collect what makes us feel good or what we’re attracted to.

Collections are beautiful to their collectors. Even the most disgusting collection is a glimpse of magic to the right person. Same as the most boring collection can excite. Essentially, every collection is extraordinary and impossible to duplicate, because even if I have the same exact baseball cards as you do, mine hold a meaning for me that’s different from yours. That individual meaning highlights the creative component—which tells me that collections are art, and the act of collection, artistry. Emotion trumps logic here. If you collect buttons/thimbles/rocks and you don’t logically know why, I can tell you. You collect those buttons/thimbles/rocks because you’re an artist and they somehow give life an extra layer of meaning for you. They make you happy.

I collect weird ideas. I collect weird stories. I collect weird questions. I write them on sticky notes and display them on my walls. For a few months, there was a blue sticky note above my desk. Why do we collect things? Next to it was a note from a year earlier that read, Weird Short Story Collection. You know what came next. You’re holding it.

There is currency in weirdness that no one told me about when I was a young weird person. There is a freedom in it too. Once an artist can block out any suggestion to conform and let go of their own fear of failure, they have found a new place where dreams can come true. Additionally, when an artist allows themselves to get weird, they give permission to everyone else in the room to get weird with them.

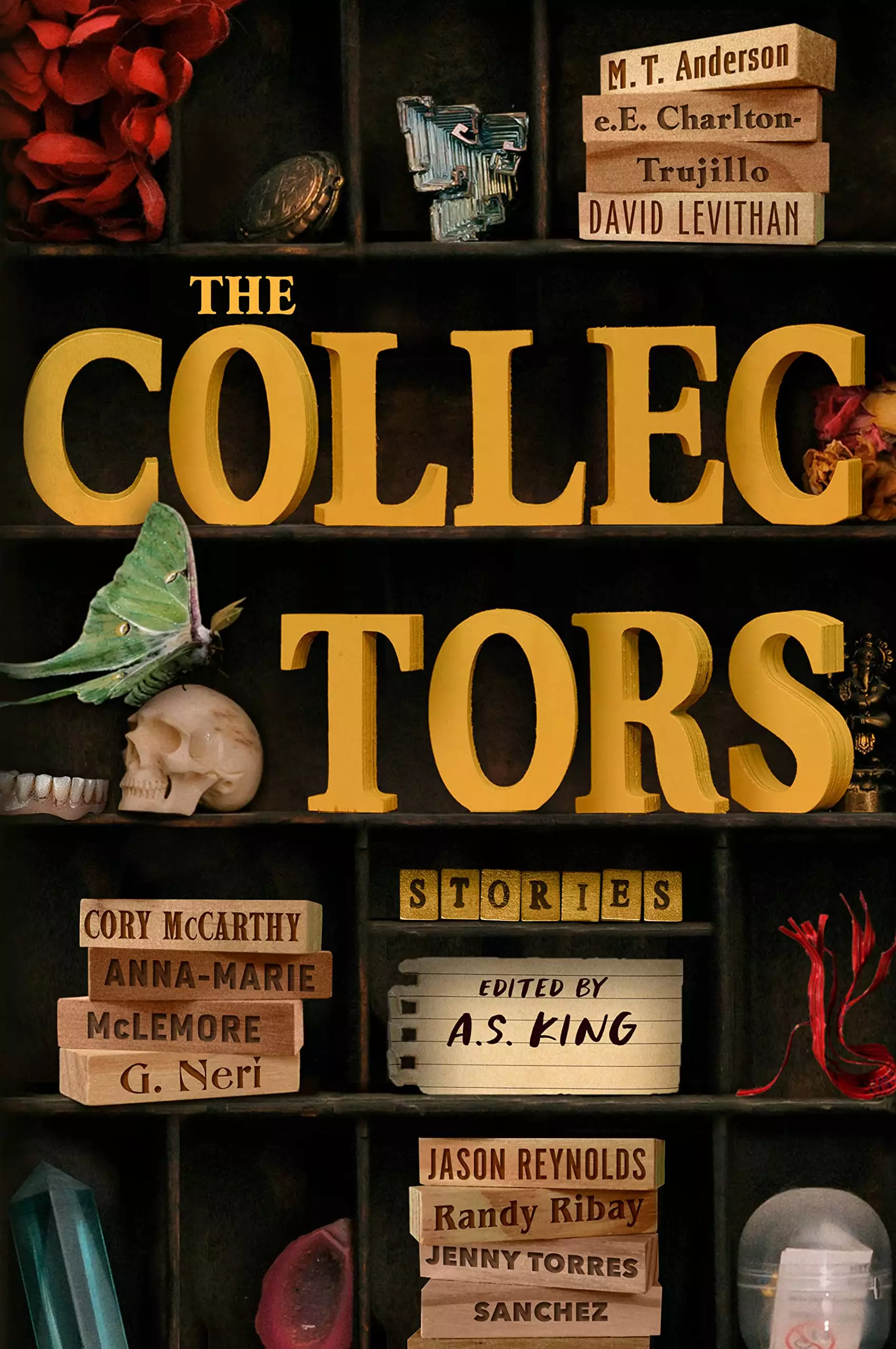

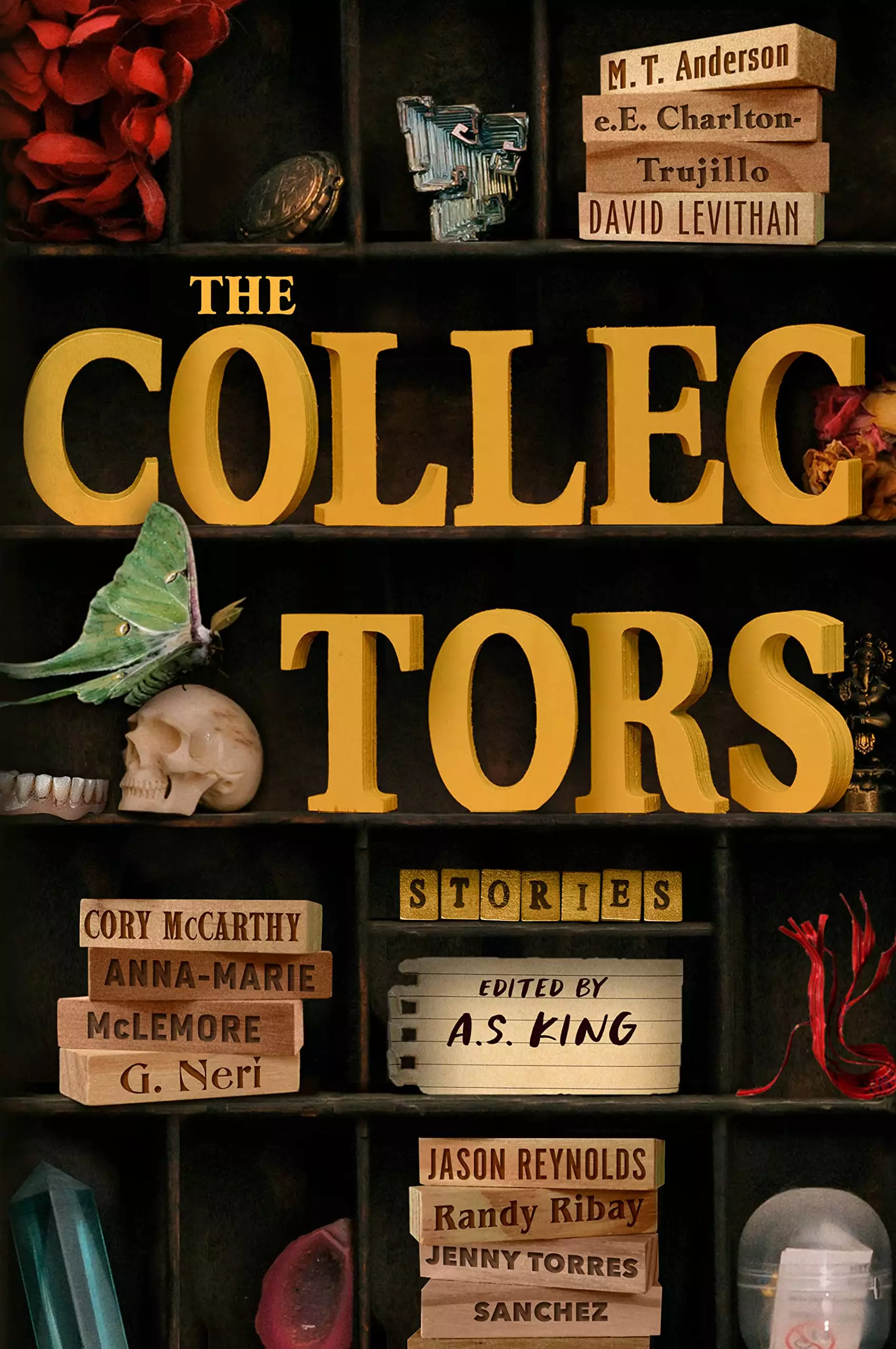

This anthology of stories is the result of me asking nine of my favorite YA writers to write me a story about a collection and its collector, and asking them to toss out conventions, as there were no rules, there was

no “normal,” and they could be as weird as they wanted. There is currency in weirdness, I said. Be defiantly creative, I said. What they’ve created here is a new, beautiful collection of curiosity and hurting and growing up and healing and loving and living.

As you begin your journey through their words, I want to extend the same invitation to you, reader, for living your life and dreaming your dreams. There are no rules. There is no normal. You can be as weird as you want. Be defiantly creative. Make art of your life, especially if you don’t consider yourself an artist—collect all the little pieces of you and make your story. When you look back many years from now, you will see something extraordinary and impossible to duplicate. You will see you.

Play House

by Anna-Marie McLemore

The first thing most people knew about Miranda Asturias was that Miranda Asturias had a beautiful mother. Miranda’s mother had hair as black as her eyelashes. Her lip line was sharp and lent itself well to quick swipes of lipstick, so that the red looked painted as precisely as if she’d used a brush. Her skin was a brown as warm as August evenings in their neighborhood, the air between streetlights just damp enough to be filmy.

If Miranda’s mother noticed the way men looked at her, she did not let on. Miranda’s mother only noticed Miranda’s father. Every morning in the kitchen, the two of them gazed at each other as though taking home the prize after a flawless draw of cards. So when Miranda’s father, after a year out of work, got a job that would take him away for most of the summer, they looked as though something had been torn out of them, each of them cored like apples.

“You’ll look after your mother, won’t you?” Miranda’s father asked her.

Miranda stood in the driveway and nodded. Then she heard herself say, “Wait,” and ran into the house.

She came back with one of her glass bluebirds. It was small enough to disappear into her father’s hand.

“For good luck,” she said, though she’d just bought the bluebird at an estate sale the week before, and had no way of knowing.

As Miranda and her mother washed the dishes that night, there was something odd about the light outside, something knocked out of place. The evening was greener, and grayer, the kind that warned of tornados. But there were no sirens. Only the prickling sense of eyes watching the windows.

“Someone’s out there,” Miranda said.

Her mother laughed. “No, there’s not.”

But as the night deepened, the prickling grew stronger. Miranda could almost hear the eyes watching, gazes tapping on the glass like thrown pebbles.

“No, there’s someone out there,” Miranda said.

“Oh, querida.” Her mother dried the last dish, set it on the stack in the cupboard. She lined up the scalloped edge perfectly with the one underneath. “Stop. You’ll give yourself bad dreams.”

Miranda’s mother did not seem to realize she was a famous beauty. She did not seem to notice how men looked at her. And this was unfortunate. Because if she had, she might have believed Miranda. They both might have felt in the air what was coming next.

• • • • • • • • • • • • •

At first, it was a couple of neighbors, men Miranda had seen greeting her father as he pruned the azaleas. One sat in a chair at the kitchen table. Another took up residence on the north end of the sofa. A third sat in the frayed armchair he must have assumed was her father’s favorite. The men came quickly, that night and the next morning, as though they’d been waiting in the shadows of the trees for her father’s car to vanish down the road.

“You two girls need a man in the house,” each proclaimed. Each tried to elbow the others out of the way. Each tried to shove ahead to get the first glass of agua de frambuesa, because her mother felt obligated to offer something to these men, who were technically guests, even though they had never rung the front doorbell.

“Don’t give them things,” Miranda told her mother as they stood at the kitchen sink. The kitchen sink seemed to be one of the few places she and

her mother could talk without the men lifting their chins to listen. At the kitchen sink, the men assumed they were talking of nothing but dishwashing liquid and scouring pads.

“If you give them things,” Miranda said, “they’ll stay.”

“They’re our neighbors,” her mother said. “We have to be polite.” She tried to give Miranda the kind of soft smile she gave everyone. But a tendon in her neck stood out, taut as the gusset on the refrigerator. Light freckled her face, the sharp glare of the morning punching holes in the lace curtains.

• • • • • • • • • • • • •

The things that made Miranda’s mother not just a beauty but a famous one were her eyes. They were green, and against the brown of her skin, they were startling in both their paleness and brightness. They were the color of bridesmaids’ dresses in shades called “seafoam” or “mermaid.” They were the mint green of the appliances that were in all the catalogs fifty years ago and were everywhere again now.

If it hadn’t been her eyes, it would have been the way she never seemed to get anything on her dresses, even clouds of powdered sugar for Christmas cookies, even the hot red spray off the Asturias family recipe for arroz. She did not wear aprons. She did not need them.

Miranda was always getting things on her clothes, especially while cooking with her mother. Especially in the summer. In the summer, she and her mother pulled blackberries from the sweet relentless brambles behind the house, the ones forever trying to swallow the garden shed whole. Her mother stirred dark jam on the stove, and the fine spray off the boiling pots always seemed to find Miranda.

This was how the apron collection started. Each came from the same garage sales and estate sales where Miranda found her glass bluebirds, wandering the yards of the living and the houses of the dead. If the deceased was a woman above a certain age, there was almost certain to be a bluebird or aprons or both. Miranda’s closet now held a fluttering array of aprons, each faintly stained. Tomatillo on the one patterned with candy corn, and on the one with the peonies. Mole rojo on the one printed with holly leaves, and the red plaid. Blackberry on the one with the cherry pattern, and the one with the whimsically angled cupcakes.

This morning, Miranda came early to the estate sale, as soon as the house opened. She always came early, but especially now. There was less chance of encountering the men’s wives. The wives glared at Miranda and her mother whenever they saw them, as though they had stolen

their husbands. Miranda would have baked them all pan dulce leavened with her own gratitude if only they would come and take their husbands back.

Miranda could tell from the smell in the deceased woman’s house that she had had a signature perfume, deep and golden and shimmery. It permeated the air between her pieces of dark-finished furniture. Miranda imagined a woman who wore red agate rather than pearls, and who might have owned neither aprons nor glass bluebirds. But Miranda found two glass bluebirds on a carefully dusted shelf—one bright as Easter egg dye, one a little greener like her mother’s eyes. And two aprons flopped over a dining room chair. The first apron repeated a delicate scene of frolicking deer in green toile, like an Austrian fairy-tale forest. The second had mallard ducks that looked so tacky in contrast, it made both aprons even more perfect.

Miranda bought the bluebirds from the woman’s daughters, and asked how much for the aprons.

“Oh.” One of them laughed, showing the bluish and lemon-hued stains on the fabric of each. “Just take them.”

• • • • • • • • • • • • •

More of them came.

“It’s not safe to be on your own like this,” the men said.

They filled the other chairs at the kitchen table. They fought for places on the sofa. They put their feet up on the windowsills. They crowded the fridge and freezer doors with their beers and liquor bottles.

Miranda barely told the men apart. One face blurred into the next, each ghostly pale in the gray-green evenings. When she did tell them apart, it was by what they drank. Budweiser, meant to prove they were real men, the crushed cans strewn like dry leaves. Vodka that smelled as strong as cleaning solvents. Jugs of grocery-store wine as big as gallon milk bottles. And one who jealously guarded a fifth of green Italian liquor that he seemed to think would impress her mother. But her mother gave the wan smile that was becoming her default expression, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved