- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

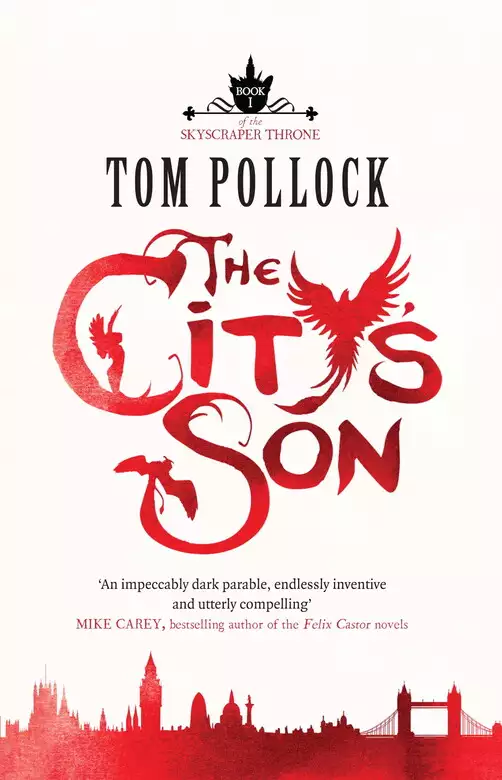

Tom Pollock's debut novel and the first volume of the Skyscraper Throne series, The City's Son is an imaginative tale of adventure set in a city that is quite literally alive.

Beneath the streets of London lies a city of monsters and miracles, where wild train spirits stampede over the tracks and glass-skinned dancers with glowing veins light the streets.

Following a devastating betrayal, Beth Bradley, a sixteen-year-old graffiti artist, is suspended from school. Running from a home that she shares with her father who has never recovered after Beth's mother's death, Beth stumbles into the hidden city and meets Filius Viae, London's asphalt-hued crown prince. And her timing couldn't have been more perfect. An ancient enemy is stirring under St. Paul's Cathedral, determined to stoke the flames of a centuries-old war, and Beth and Fin find themselves drawn into the depths of the mysterious urban wonderland, hoping to prevent the destruction of the city they both know and love.

Release date: August 2, 2012

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 422

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The City's Son

Tom Pollock

I pick up the pace, racing eagerly over the tracks with my bare feet. Sweeping my spear in a low arc, I feel for the electricity in her trail – divining for the monster.

Around me, the city is oblivious. Under the brick arches, people are walking in and out of the newsagent’s and the off-licence; a couple of schoolkids are chatting, swapping tall stories about some girl they fancy. And then, over their laughter, the moan of evening traffic, the bass from distant music and all the other sounds of the city, I hear her wild, shrieking brake cry.

My heart clenches. They have no idea of the danger they’re in, none of them, not now she’s loose – now she’s awake.

In Mater Viae’s name, she’s awake.

*

I’d picked up her trail at King’s Cross, in the nest of interwoven steel north of the station. She’d left her train, a big freight engine, paralysed without her spirit to animate it. The driver had just sat there stupefied, no clue what was wrong with his machine. Other trains tailed back from the obstruction in strings of brightly lit windows, their passengers grumbling, playing with their phones and wondering what the hell the hold-up was.

I’ve pursued her doggedly since then: the relentless hunter.

Well … almost relentless.

Once, I let her go – I had to. Her trail led through the St Paul’s construction sites, past the Cathedral, right under the claw-like shadows of Reach’s cranes.

Reach – the Crane King. Even I can’t trespass on his territory. I swear I could feel his metal-strutted fingers stretching out to claim me as I turned to run.

I found the trail again easily enough. The dead boy made it hard to miss. He lay tangled across the tracks under a burnt-out signal box. Judging by his size, he’d been about fifteen, maybe only a few months younger than me, but the damage to his face made it hard to be sure: the dried-out skin was cracked and blackened, and empty sockets gaped where the eyeballs had boiled away. Only the metal spraycan in his right hand had survived the voltage intact.

It wasn’t the body that made me hesitate – sad to say, I’ve seen uglier corpses. It was the bloody wheel-print bisecting the boy’s chest, at right angles to the rails, running across the tracks. For a moment I struggled to make sense of it. Then I saw the hole smashed through the bricks in the viaduct wall and a prickle of disbelief ran up the back of my neck.

She’d escaped the railway. She’d got out.

How in Thames’ name—?

It was then that I started to doubt: if she was that powerful, would I really be able to bring her down?

Out across the city the streetlights were starting to shine as the Sodiumite dancers woke, stretching and warming their limbs to a glow inside their glass bulbs. I slid my fingers into the cracks in the brickwork and pushed myself over the edge of the viaduct, easing myself down to the pavement below. Then, nimble, in the gathering gloom, I slipped into the streets.

Now I’m waiting in a dead-end alley, listening to the steady drip of water from a rusting pipe. I calm myself, letting the tap of the water become the rhythm of my heartbeat. My stance is open, my spear ready.

This is where her trail ends.

Thrum-clatter-clatter, thrum-clatter-clatter …

I can feel her vibration through the ground. A fox squirms out from behind a couple of steel bins and runs for the road, trailing stink. I let my breath stream out in a slow hiss.

Thrum-clatter-clatter …

The concrete shale on the ground starts to shift and a breeze picks up, spattering rain against my cheek. The burnt smell is emanating from the wall at the end of the alley, breathing out of the pores in the brick itself.

A high-pitched wail fills the air: steel shrieking on steel like screaming horses. The clatter grows louder and the bins clang as they are shaken to the ground.

I hear the ghost of a steam-whistle, her mournful, obsolete battle-cry, and I hunker down low. Light starts to bleed through the mortar ahead of me, outlining two glaring, full-beam eyes. I hear the clash of her wheels, stampeding towards me on a path of lighting. The scream rises out of my throat to greet her, cursing her by all of her names: Loco Motive, Bahngeist, Railwraith—

—and as she roars out at me, I leap sideways and strike—

‘Beth, come on,’ Pencil whispered, ‘we need to go.’

Beth studied the picture she’d sprayed on the tarmac of the playground. She flipped her aerosol over a couple of times in her hand.

‘Beth …’

‘It’s not finished yet, Pen,’ Beth said. In the dim backwash from the lights nearby she could just make out the Pakistani girl’s fingers worrying at her headscarf. ‘Don’t be chicken.’

Pencil paced fretfully back and forth. ‘Chicken? What are we, like ten? Have you been sniffing your own paints? I’m not kidding, B. If someone comes, this will get us expelled.’

Beth started shaking the spray can up. ‘Pen,’ she said, ‘it’s four a.m. School’s locked up. Even the rats have given up and gone home. We covered our faces from the cameras when we jumped the wall, but there’s sod all light there anyway. There’s no one around and we can’t be ID’d so what exactly are you worried about?’ Beth kept her voice calm, but there was a taut knot of excitement in her chest. She swept her torch over the picture at her feet. Her portrait of Dr Julian Salt, Frostfield High’s Head of Maths, was coming out well, better than she’d expected, especially for a rush job in the dark. She’d got his frowning eyebrows down perfectly, and the hollow cheeks and the opaque, threatening glasses. The weeds bursting through the tarmac added to the effect, looking like unkempt nasal hair.

In fairness, Beth had also given him necrotic peeling skin and a twelve-foot-long forked tongue, so she was obviously using some artistic licence, but still …

It’s unmistakably you, you shit.

‘Beth, look!’ Pen hissed, making Beth jump.

‘What?’

‘Up there—’ Pen pointed. ‘A light …’

Beth glanced up. One of the windows in the estate overlooking the school was glowing a soft, menacing orange. She exhaled irritably. ‘It’s probably just some old biddy going for a midnight wizz.’

‘We can be seen from there,’ Pen insisted.

‘Why would anyone even care?’ Beth muttered. She turned back to the picture. Everyone in year 12 at Frostfield knew she and Salt were enemies, but that was just the usual teacher-versus-student aggro, and it wasn’t why she was here. It was the way Salt treated Pen that demanded this retribution.

She didn’t know why, but he seemed to derive this vicious delight from humiliating her best friend. Salt had put Pen in half the number of detentions he’d sentenced Beth to, but she was always on the verge of tears when she came out of them. And in Monday’s maths lesson, when Pen had asked to go to the toilet, Salt had point-blank refused. He’d gone on talking about quadratic equations, but he hadn’t taken his eyes from Pen. There’d been this smile on his face as though he was daring her to defy him – as though he knew that she couldn’t. Pen’d kept her hand raised, but after a while her arm had started to shake. When she’d doubled-over with the pain of holding it in, Beth had dragged her bodily her from her chair and bundled her out of the room. As they ran down the corridor, they’d heard the laughter start.

Afterwards, standing behind the science block, Beth had asked, ‘Why didn’t you just leave? He couldn’t have stopped you, why not just walk out?’

Pen’s face was fixed in the clown-smile that meant she was panicking inside. ‘I just …’ She’d half swallowed the words, and kept her eyes fixed on her shoes. ‘I just thought every second that went by, if I could hold on just one more second, one more, it would be okay. And I wouldn’t have to … you know.’

Cross him. Beth had filled in the end of the sentence.

She’d hugged her friend close. Beth knew there was strength in Pen, she saw it every day, but it was a strength that withstood without ever resisting. Pen could soak up the blows but she never hit back.

It was then that Beth had decided that something needed to be done. And this – this was something.

She trained the beam of her torch onto the painting and the tension in her chest was replaced by a warm glow of satisfaction. A nightmare in neon, she thought. Ugly suits you, Doc.

‘Beth Bradley,’ Pen whispered. She still sounded scared, but this time she also sounded a little reverential. ‘You are a proper grade-A nutcase.’

‘Yeah, I know,’ Beth said, a smile creeping onto her face. ‘But I am really good—’

A high-pitched whine cut through the night: police sirens, fast approaching. Instinctively Beth dropped to a crouch and yanked her hood up over her short, messy hair.

‘Bloody hell,’ Pen whispered, her voice panicky, ‘I told you they’d seen us! They must have called it in – they probably think we’re here to steal something.’

‘Like what?’ Beth muttered back. ‘The canteen’s secret recipe for mouse-turd pie? It’s not like the school’s got anything worth nicking.’

Pen tugged Beth’s sleeve. ‘Whatever – we need to get out of here.’

Beth yanked her sleeve away and dropped to both knees, frantically adding extra shading to the jaw-line. This had to be just right.

‘B, we need to go!’ Pen was hopping from foot to foot in agitation.

‘Then go,’ Beth hissed.

‘I’m not going without you.’ Pen sounded offended.

Beth didn’t look up. ‘Pen, if you don’t get running, and I mean right now, I’ll tell Leon Butler it was you who Tipp-Exed that poem on his desk.’

There was a moment’s shocked silence, then, ‘Bitch,’ Pen breathed.

‘Leon, my lion, I would be all your pride. And not merely in it…’ Beth quoted in a sing-song whisper. She couldn’t help grinning as Pen took off, swearing under her breath.

Beth got her feet up under her, ready to run even while she drew. The sirens were really close now. Waaaoooh—The whine soared once more, then cut off in mid-cycle. She heard car doors open and then slam. There was a rattling on the gates behind her. The school was locked up and the cops were climbing in just like she and Pen had. Beth sprayed colour into a fat cluster of warts under one eye.

‘Oi!’

The shout sent a jolt of fear down her spine. Gross enough, she thought. She stuffed her stencils and paints back into her rucksack, snapped off the torch and ran. Heavy boots thudded on the tarmac behind her, but she didn’t look back, there was no point in showing them her face. She sprinted with her head down, the wind rushing in her ears, praying that the police behind would be laden down with stab vests and truncheons, praying she’d be faster.

She looked up, and panic clutched at her gut. The cops were chasing her into a dead end. The highest wall in the school reared in front of her. It backed onto the dense tangle of scrub and trees around the train tracks: ten smooth, unclimbable feet of it. She drove her legs harder, trying desperately to build momentum, and jumped.

Her fingers scrabbled at concrete, inches short of the top, and she fell back.

Shit.

Again she threw herself at it; again she came up short. Breathlessness and despair made her chest ache.

‘B.’ A whispered syllable. Beth whirled around. Pen was running along the base of the wall towards her, her headscarf pulled bandit-style over her mouth.

‘I told you to go,’ Beth hissed, both furious and relieved.

‘As if. The minute I clocked this I knew you were too short for it.’ She dropped to one knee and cupped her hands.

Beth flashed her a quick grin and stepped into the boost; a moment later she dragged Pen up after her.

‘Split,’ Beth whispered as she hit the ground on the other side. She winced as pain spread over her hands; she’d landed them in a bed of nettles. ‘I’ll catch you up at the usual.’

They could hear their pursuers huffing and swearing on the other side of the wall.

One of the men panted, ‘Give us a boost!’

Pen veered to the right and Beth ran left, zigzagging between the trees. Her breath wheezed in and out, staccato in her ears. Twigs and discarded bottles crunched under her feet. A fence blocked her way, but she saw a ragged hole at the base and she dived for it, wriggling through into a looming concrete estate. She ducked down behind a rusting old car with broken windows, gasping for breath. A train rushed over a nearby bridge, angled slabs of light rocketing though the darkness. She tried to listen past its dying clatter and her own slamming heartbeat, but she could hear no sounds of pursuit.

She rooted in her backpack for a crumpled leather jacket, slipped off her hoodie and shoved it in on top of the paint cans. Adrenalin made her legs wobble so much she staggered and nearly fell.

Nice, Beth, she thought sarkily, very cool. Now if you can just stop walking like a concussed turkey you might actually get halfway down the street before the Filth pick you up.

Pulling her jacket closed, she walked on, casual as she could.

Pen was waiting at the corner of Withersham and Shakespeare Roads, where redbrick terraces with fussy front gardens stretched away on both sides. As she always did when she was nervous, Pen was checking and rechecking her reflection in her compact mirror, studying for the tiniest flaw.

Beth smiled despite herself: only Pen Khan would apply mascara for a night of criminal vandalism.

The postbox Pen was standing next to was probably the most graffiti’d piece of square footage in all of London: a rainbow-riot of obscenities, slogans, cartoon animals and grotesque monsters. It was local graffiti tradition to make a contribution to the Withersham box, so last year Pen and Beth had painted themselves on in ‘Wanted’ posters, pulling stupid faces. Those mugshots had long since been buried beneath the work of the neighbourhood’s other artists.

Beth flipped a lazy salute as she approached. Pen just stared back. ‘One of these days, Elizabeth Bradley,’ she said slowly, ‘you’re going to get me expelled. My parents will bloody disown me.’

Beth grinned at her. ‘Oh well, I’ll have done you a favour, then. You could come tagging without having to sneak around.’

‘Thanks: when I’m a homeless, starving disgrace to my family, that’s the thought that will keep me warm, I’m sure.’

Beth scuffed her trainer along the tarmac and smirked at Pen’s sarcasm. ‘So come live with me,’ she offered. ‘At least you could marry whoever you like.’

Pen’s lips thinned and tension crept into her voice. ‘And your grand total of two boyfriends makes you the world’s wedding guru how, exactly?’

‘Two more than you,’ Beth muttered, but Pen ignored the interruption.

‘My folks will help me find the right person,’ she said. ‘It’s about experience, that’s all. They know marriage, they know me, they—’

Beth interrupted, ‘Pen, they don’t even know you’re here.’

Pen flushed and looked away.

Suddenly ashamed, Beth stepped forward and hugged her best friend close. ‘Ignore me, okay?’ she murmured quietly into Pen’s headscarf. ‘I’m being a cow, I know I am. I’m just scared your folks will hitch you to some accountant with a beige suit and beige underwear and a beige bleeding soul and I’ll have to redecorate the walls of East London all by myself.’

‘Never happen,’ Pen whispered back, and Beth knew it was true. Pen would never walk away from her. She looked over Pen’s shoulder. The sky was growing light. Telephone poles stretched down the street, their cables like reins drawing in the sunrise. When day broke, this day, and every day after it, Beth knew it would break over the two of them, side by side.

‘You okay?’ she asked.

Pen gave a fragile little laugh. ‘Yeah. Only— That was all a bit bloody hairy, you know?’

‘I know,’ said Beth. ‘That was backbone, hardcore – proud of you, Pencil Khan.’ She hugged her tighter for a second, then let go. ‘We won’t get much sleep tonight, though.’ Her neck muscles were taut and her eyes wanted to close, but still she felt restless. ‘I don’t suppose I could persuade you to skip the first couple of classes with me tomorrow morning?’

Pen nibbled her lower lip carefully, not smudging her lip-gloss. ‘You don’t think that’d make us a leetle bit conspicuous?’

Obvious when you thought about it, Beth conceded, but as always, it took Pen to see it. She was like a small animal, always finding exactly the right spot for camouflage: she had an instinct for anything that wouldn’t blend in.

‘How’s about we tag the rest of the night, then?’ Beth countered. ‘Push on through – I’m feeling inspired.’

Pen had told her mum she was staying at Beth’s tonight. Beth hadn’t needed to clear anything with anyone, of course. Out here in the streets it was easy to forget that she belonged anywhere else.

Pen shook her head at her own foolishness, but she unzipped her hoodie and pulled out her own spraycan. ‘Sure,’ she said. ‘I think I’ve got some game tonight.’

They ran west into the heart of the city, ahead of the dawn, dodging between hoardings with peeling posters and boarded-up shop windows.

Beth crouched beside a pile of broken concrete next to some roadworks and sprayed a few black lines. To most people they’d look like tar or shadows; you had to be in exactly the right spot to see the rhino, formed by paint and the edges of the concrete itself, charging out at you. Beth smiled to herself. The city’s a dangerous place if you don’t pay attention.

She’d left pieces of her mind like this all over London, and no one else knew where. No one, except maybe Pen.

She glanced over at the taller girl. When the two of them swapped secrets it wasn’t like the hostage-exchange Beth sometimes saw with other girls. Pen genuinely cared, and that meant Beth could risk enough to care, too. Pen was like a bottomless well: you could drop any number of little fears into her, knowing they would never come back to haunt you.

It started to rain: a thin, constant, soaking drizzle.

Pen wrote her poems on kerbs and inside phone boxes, romantic counterpoints to the pink-and-black business cards with their adverts for bargain-basement sex, carnal specialties listed after their names like academic degrees:

CALL KARA FOR A WICKED TIME: D/s, T/V, NO S, P OR B

‘… you might be the puzzle-piece of me,

I’ve never seen.’

‘That’s gorgeous, Pen,’ Beth murmured, reading over her shoulder.

‘Think so?’ Pen eyed the verse worriedly.

‘Yeah.’ Beth knew eight-tenths of sod-all about poetry, but Pen’s calligraphy was beautiful.

The sun slowly bleached the buildings from the colour of smoke to the colour of old bone. More and more cars passed them by.

‘We should head,’ Pen said at last, tapping her watch. She frowned, considering something, then added, ‘Maybe we should catch separate buses. We don’t normally arrive at school together – it might attract attention.’

Beth laughed. ‘Isn’t that a little paranoid?’

Pen gave her a shy, almost proud smile. ‘You know me, B. Paranoid’s where I excel.’ She led the way out of the narrow alley and they slipped into the hustling crowd.

Pen took the first bus.

Beth felt like a spy or a superhero, sliding back into her secret identity as she waited for the next.

Maybe it was one of his worms that found me, nosing through the thick sludge at the edge of the river, or perhaps a pigeon, wheeling overhead, from one of the flocks that nest on top of the towers. All I know is that when I wake, Gutterglass is crouched over me.

‘My, my, you’re quite the mess, aren’t you?’ the old monster says gravely. ‘Good morning, Highness.’

He – Glas is a ‘he’ this time – looks down at me with his broken eggshell eyes. Old chow mein cakes his chin in a slimy beard. His rubbish-sack coat bulges as the rats beneath it scramble about.

‘Morn—’ I begin to say, then the pain of the burns washes over me, choking off the words. I inhale sharply and wave him back. I need air. He’s nabbed a tyre from somewhere and his waist dissolves into a single wheel instead of his usual legs. Lithe brown rodents race around the inside, rolling him backwards.

I grit my teeth until I reach a manageable plateau of agony, then, groggily, I take in my surroundings. I’m on a silt strand under a bridge on the south side of the river – Vauxhall, judging by the bronze statues lining the sides. The sun shimmers high in the sky. ‘How long?’ My throat feels as tight as a rusted lock.

‘Too long, frankly,’ Glas replies. ‘Even the foxes came in before you did. Do I need to remind you that you are my responsibility? Assuming, of course, that responsibility is a word that your grubby little Highness comprehends? If anything happens to you, I’m the one who’ll have to answer to Mater Viae.’

I shut my eyes against the harsh light, biting back the obvious retort. Mater Viae, Our Lady of the Streets, my mother – left more than a decade and a half ago. I hate how Gutterglass still bloody nearly genuflects whenever he says her name.

‘If she ever comes back,’ I say, ‘do you really think she’ll care which particular pile of London crap I sleep on?’

‘When she comes back,’ Glas corrects me gently.

I don’t argue with him, because it’s not nice to call a man’s faith ridiculous.

Most mornings you can find him (or her, if that’s the body Glas makes that day) at the edge of the dump, looking towards the sunrise over Mile End, waiting for the day when stray cats march in procession down the pavements and the street signs rearrange themselves to spell Mater Viae’s true name: the day their Goddess returns.

Air sighs out of his tyre and he sinks down beside me. He opens the black plastic of his coat and chooses one of the syringes strapped there. He’s been raiding hospital bins again. He slides the tip into my arm, depresses the plunger and almost immediately the pain ebbs.

‘What a mess,’ he mutters again. ‘Sit up. Let’s take a look at the damage.’

I creak gradually into a sort of shell-shaped hunch, which is the best I can manage. Neat cross-stitches lace my cuts together; the needle that made them has been thrust back in Glas’ arm and the left-over thread is waving gently in the wind.

‘Wow,’ I croak, fingering the stitches, ‘I really must have been out cold to not feel those.’

‘Dead to the world,’ Gutterglass agrees. ‘Not literally, though, thanks in no small part to yours truly, and in no part at all to you.’

I have to use my spear as a lever to stand up. I can still feel the electric buzz in the iron where I stabbed the wraith. Glas dusts me down, wiping at my cheek with split penlid fingers. Glas is oddly fastidious – I guess having to make himself a new body out of the city’s rubbish every day means he knows where it’s all been.

‘I was hunting—’ I start to tell him about last night, but he isn’t listening.

‘Look at you, you’re filthy—’

‘Glas, this Railwraith—’

‘Doing these stitches has destroyed my fingers,’ he moans. ‘Have you no heart at all for a poor old rubbish-spi—’

‘Glas!’ I snap, a little harder than I mean to, and he recoils and shuts up, staring at me reproachfully. I exhale hard and then just say it. ‘The wraith got loose from the tracks. It got free.’

For a long moment the only sound is the patter of the breeze on the surface of the river. When Glas finally speaks, his voice is flat. ‘That’s not possible.’

‘Glas, I’m telling you—’

‘It’s not,’ he insists. ‘Railwraiths are electricity: its memory, its dreams. The rails are their conductors. They can’t survive away from them for more than a few minutes.’

‘Well, take it from the son of a Goddess whose bony arse it kicked around the block, three miles from the nearest stretch of track: this one can!’ My shout echoes off the bridge’s foundations. I squat down, trying to work the tension out of my temples with my fingertips.

‘Glas, it was so strong,’ I say quietly. The memory of the fierce white voltage of its teeth is seared into my skin. I shiver. ‘I wounded it, but— It must have left me for dead. I’ve never met a wraith like it. It didn’t even try to run, just came right at me …’

‘… as though it was it that was hunting you?’ Glas asks, and I look up sharply.

Because that’s exactly what it was like.

Gutterglass’ voice is very quiet. All of the rats and worms and ants that animate him go still and for a moment he looks dead. ‘Filius,’ he says softly. And he doesn’t sound confused any more. He sounds very, very frightened. ‘Did anyone see you hunting that wraith?’

‘What? No. Why?’

‘Filius—’

‘No one saw me, Glas, I was just hunting. I was—’ Then I falter, because that isn’t quite true: somebody did see. A sick feeling swells in my stomach as I realise what he’s asking.

‘It went through St Paul’s,’ I whisper.

‘The Railwraith entered Reach’s domain,’ Glas says.

I nod as I feel the cold seep through me, like my bones are blistering with ice.

‘… and emerged on the other side,’ he continues, his voice grim, ‘loose from the rails, more angry and more powerful than it had any rightful way of being, and coming after you.’ I can hear the strain of forced calm on his borrowed vocal chords. ‘Filius,’ Glas says, ‘there’s an ugly possibility here you need to face up to.’ He sinks down until his shells are level with my eyes. ‘What if that wraith didn’t “get loose”? What if it was set free—?’

The question hangs in the air unfinished. I complete it in my head: What if it was set free by Reach?

Across the river, the boom and clang of construction drifts from the St Paul’s sites. His cranes grasp at the Cathedral like it’s an orb of office.

Reach: the Crane King. My mother’s greatest enemy. His claws have been part of my nightmares for as long as I’ve been dreaming.

He could do it. It dawns on me now, as it must have done on Glas, that Reach is an electric expert. His cranes and diggers, his pneumatic weaponry, they’re all powered by it – so he could have found a way to channel that power into a wraith, to set it, frenzied and burning, on my tail: an opportunistic attack.

‘What if it’s finally happening, Filius?’ Gutterglass whispers, half to himself. ‘What if Reach is coming for you?’

I grip my spear so tightly it feels like the skin on my knuckles could split

‘We have to get you home – now,’ Glas says. He’s wheeling himself round and round in circles, suddenly all urgency. ‘I need you back at the landfill where it’s safe, until I can find out what’s going on. If this is Reach, he won’t stop with a Railwraith.

‘Soon there will be wolves and – Lady save us,’ he murmurs fervently, ‘wire.’ He begins rolling towards the edge of the bridge, yanking me by the arm, and I have to drag my feet in the sand to wrench myself free.

What if Reach is coming for you?

… Reach is coming …

The mantra goes around and around in my head, dizzying me, but it makes no sense: why now? I’ve been here for sixteen years without my mother’s protection. What’s he been waiting for?

But the longer I think about it, the more horribly easy it gets to believe. Reach has been the monster in every fairy-tale I’ve ever been told. My mother hated him, and Glas hates him, and I hate him too. I can feel that hatred clotting around my heart.

Reach is coming … and deep down, I always knew he would.

‘Filius?’ Glas beckons impatiently. ‘We need to move.’

I straighten up, wincing at a fresh wave of pain from my burns, and shake my head.

Glas arches a dust-drawn eyebrow. ‘This is no time to be stubborn, Fili. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...