- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

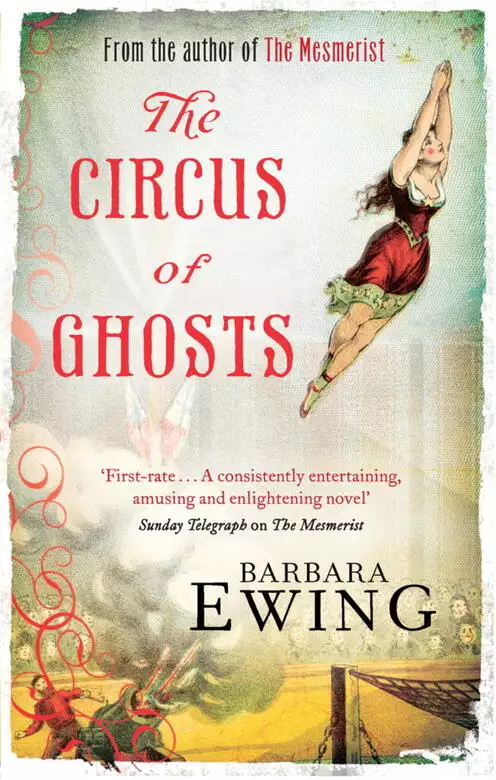

Synopsis

New York, late 1840s, and in the wild, noisy, brash and beautiful circus of Silas P. Swift a shadowy, mesmeric woman entrances crowds because she can unlock the secrets of troubled minds. Above them all her daughter sweeps and soars: acrobat and tightrope-walker. People cannot take their eyes from the mysterious woman in the Big Top who can help so many others - but she cannot unlock dark, literally unspeakable, memories of her own. In London memories fester in the mind of an old and venomous duke of the realm. He plots, with an unscrupulous lawyer (and a huge financial reward) against the mother and the daughter: to kill one, and to abduct the other and bring her across the Atlantic to him: She is mine. The actress and mesmerist Cordelia Preston and her daughter Gwenlliam live with their unusual family in the exciting new city among exciting new ideas: the telegraph, the daguerrotype, anaesthesia, table-tapping. And among the dangerous street-gangs of New York also, whose raw violence meets Cordelia and Gwenlliam and those that they love, with unexpected results.

Release date: July 28, 2011

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Circus Of Ghosts

Barbara Ewing

shouted.

‘Find the harlot! Find the whore! Find the actress!’

‘Our investigations have shown, my Lord, that she has, some time ago, travelled to America and – I am sorry to have to inform

you – joined a circus.’

‘What do you mean by “your investigations”? It was there for all the world to see and laugh over in the Times newspaper!’

‘Indeed the matter was reported in the newspapers, your Lordship.’

‘Well, find the harlot!’

‘America is a large and unchartered country, my Lord.’

‘Well, if it is large and unchartered the whore will be in one of the obvious places, won’t she! Washington. New York. Boston.

Do you think I do not know the geography of that disloyal, revolutionary land of traitors and Irish clod-hoppers and democrats?

Of course she would go there, the actress-harlot! She killed my son.’

Mr Doveribbon senior (wealthy lawyer to the nobility, a large man used to comfort but not invited to sit at this meeting)

cleared his throat, exchanged an uneasy look with his son Mr Doveribbon junior (putative lawyer and man-about-town). ‘My Lord,

you must, I think, disabuse yourself of that notion for it is generally agreed and known that your son was killed by his own

wife.’

The duke spluttered and gesticulated, and in doing so knocked the bottle of whisky on to the marble floor where it smashed,

ejaculating its golden contents over Mr Doveribbon junior’s fine boots, much to the elegant young man’s horror. Sickly whisky

fumes rose and a manservant appeared miraculously with broom and bottle, and the expression of a Christian martyr.

‘Lady Ellis may have killed my son nominally and wielded the dagger, but who killed my son morally? The whore! The actress!’ (It was perhaps incongruous to hear the word moral in that Mayfair room of scoundrels, for not only the duke but the manservant, the lawyer, the lawyer’s son, and the doctor

trying to listen unobserved outside the door, would not have, any of them, recognised the meaning of the word moral even if it had come up and punched them on the jaw.) ‘I want the harlot actress disposed of and I want the daughter – whatever her name is – my blood, mine, my grand-daughter, returned to me, mine. She is to look after me. She is the daughter of my son even if her mother is a whore.’ He imbibed whisky from the second

bottle. ‘I am alone.’ Tears formed in his crafty eyes, ran down his crafty face. ‘I want her here with me.’ And then the tears

dried as suddenly as they had appeared. ‘And when I get her I can overturn the disgusting, money-grubbing intentions of my cousin’s son, the locust, who waits for me to die so that

he can inherit Wales!’

Again Mr Doveribbon senior cleared his throat. ‘The girl is female off-spring, my Lord. In law she would not be able to inherit

any part of Wales that you may own.’

‘The ancient and noble family of Llannefydd is above the law! I will change the law! That girl had more sense than her sister

for whom I did so much, and the nimsy-whimsy-pimsy stupid boy,’ (again whisky spluttered) ‘and she shall be returned to me as is my right! And the mother disposed of!’

‘When you say “disposed of” your Lordship, you mean …’

‘What do you think I mean, you fool? Surely an Irish clodhopper can be paid to find a dark corner in that traitorous land! Do I have to spell

out everything to you?’ And then he observed the lawyer and his son with a slow look of cunning and his voice took on a silken

tone. ‘My purse will – of course – be open to you. All expenses. Any bills paid. High fees. Just find that actress-harlot!

And bring me my grand-daughter!’

Mr Doveribbon senior, now that serious money was being discussed, considered. ‘I would have to send my son to America. He

is a most presentable Englishman.’ Mr Doveribbon junior with his whisky-stained boots looked further alarmed. He was indeed

presentable, in fact he knew he was even devastatingly good-looking, but he was not stupid and he was (unbeknownst to his

father) heavily involved in some dubious land-buying in newly developed housing sites round the Edgware Road, so he had his

own plans and they did not include travelling to any part of America. ‘It would be a long and arduous and expensive task,’

his father continued, ‘to find the mother and the girl.’

‘Dispose of the mother! That whore with the black and white hair! Nothing will come to any good if she is to interfere. Dispose

of the mother and bring me my grand-daughter!’

‘We would need a very large advance on expenses, your Lordship.’

Again the cunning, crafty eyes. ‘No paltry advance! Dispose of the mother, bring me my grand-daughter, and I will give you ten thousand pounds!’ At this pronouncement both Doveribbons

swooned slightly: Ten thousand pounds? Ten thousand pounds was unheard of riches, even in the murky world of the legal profession.

Nevertheless, instinct nudged Mr Doveribbon senior to refuse this particular set of instructions. The Duke of Llannefydd was

one of the richest and most prominent nobles in Britain, certainly, but he was also known as untrustworthy, even among those

who manoeuvred where untrustworthiness was the norm. And ‘disposing of’ was something Mr Doveribbon left to wilder men. However:

ten thousand pounds echoed. Also: his son was extremely presentable and – Mr Doveribbon’s dreams suddenly leapt higher – might even make an impression

on the heiress. Greed and instinct battled in the mind of Mr Doveribbon senior.

Greed won.

All classes of people in New York (which called itself class-less) attended Mr Silas P Swift’s Amazing Circus: something about

the wild, and the exotic, and the vulgar, and the dangerous. In the brash, expanding, crowded, noisy, money-making city of

New York Mr Silas P Swift’s Amazing Circus was the most notorious – and the most visited; the bright, gaudy pennant flying

above his huge Big Top could be seen from Broadway and his circus posters were larger and brighter and more brazen than any

other.

ROLL UP! ROLL UP!

MR SILAS P SWIFT’S AMAZING CIRCUS

presents

the Acquitted MURDERESS from LONDON

MISS CORDELIA PRESTON, FAMOUS MESMERIST!

And her daughter Miss Gwenlliam Preston,

STUNNING ACROBAT!

Accompanied by the most talented riders and artists of the Circus World

And WILD ANIMALS including

A DANGEROUS LION FROM AFRICA!

A HUGE ELEPHANT FROM AFRICA!

A CAMEL FROM ARABIA!

DANCING HORSES!

BEAUTIFUL ACROBATS, MEXICAN COWBOYS!

FEARLESS FIRE SWALLOWERS!

CLOWNS AND MIDGETS!

The most exciting show ever seen in our country!

Only $1.00 (children 75 cents)

Murderess, Mesmerist were the words that echoed, like Dangerous Lion from Africa: crowds, and dollars, poured into Mr Silas P Swift’s Big Top, with its huge canvas walls and its sawdust floors and its planked

wooden seats for fifteen hundred people; hawkers set up stalls nearby to sell oysters and ale and sarsaparilla and big pies.

This afternoon the City Aldermen came, with their children in elegant smocks; not so far from them, but back in the shadows,

were members of the most vicious criminal gang in New York, sprawling on the precarious wooden seating and laughing and eating

the big pies. They wore dark shirts, and gold earrings in their ears.

The lion-tamer had already escaped certain death (as he did twice daily); the elephant was trumpeting loudly as clowns juggled

coloured balls, and the top-hatted, red-coated circus master cracked his whip. Fire-eaters breathed flames at the audience who stank of sweat and excitement and ale, and who in

their turn breathed in the thrilling, peculiar circus smells of wild animals and sawdust and canvas and oil-lamps and dung

and fire; the brass band played patriotic marches. And all the time the circus troupe kept up, as usual, a running commentary

among themselves about the audience, in among the cries of HOUP-LA! and HURRAH! and the roaring of the lion; the audience came to be entertained by the circus, did not perhaps know that they were themselves

entertaining also. Pretty girls and pompous Aldermen and mean-mouthed gangsters alike: they may not have observed they were

observed but indeed they were; the performers were calling in their own circus language to each other: a mixture of new American

slang – high-falutin’, humbug – plus theatrical gestures that may have seemed part of the act and Spanish whoops from the charros, the wild and clever Mexican cowboys. It was one of the fire-eaters who pointed out the City Aldermen, those men with such favours to dispose, and one of the midgets

ran straight up the planked wooden steps in the audience and planted a kiss on to the cheek of one of them: whatever the Alderman

thought of this grizzly rather un-fragrant gesture he, of course, waved to the crowd in acceptance of the honour and chuckled

heartily and acrobats swung higher and higher and bright oil-lamps shone everywhere and although the dangerous gang members

sat far away at the back, the light from the lamps still occasionally caught their shining earrings and the gold crosses around

their necks. And sitting amongst the gang members, the tallest one of them all: wild hair, thick braces; it was only if you

looked very carefully that you could see that the tall, wild figure was a woman. And it was only if you happened to be looking

very, very carefully indeed that you might have seen the wild-haired woman and one of the City Aldermen (a most unlikely combination) exchange an almost imperceptible nod.

The midgets ran and somersaulted and the charros rode faster and faster round the ring, past the angry, trumpeting African elephant and past the white-faced clowns with their

big red painted smiles and their false red noses and their black over-sized shoes, and the brass band with its tuba and trumpets

and drums played on.

And Silas P Swift was, above all things, an incomparable, theatrical showman.

Suddenly the music stopped. Suddenly the lamps were turned low by the clowns and the charros and the midgets and the fire-swallowers and suddenly, now, the acrobats flew like hazy, silent birds over the audience. And

then his star performer, his beautiful, scandalous, infamous Mesmerist, slowly emerged out of the shadows at the back of the

Big Top and there was an intake of breath from the audience and in the half-light they saw a beautiful, older woman, draped

in long, drifting scarves. And as the drums rumbled softly she lifted her arms, long glittering scarves fell from her head

and they saw she had huge eyes and a pale face. And they saw that she had one extraordinary white streak of hair among the

dark, as if she had once suffered some shock that had turned part of her hair ancient, or wise, or phantasmal. Then a strange

husky voice, used to big spaces, called, Whose pain can I help here? And whether they thought she was a murderess or not, people came forward, or were brought forward by their families. For

they had heard of mesmeric powers, and they were people who wanted miracles. From the shadows the Mesmerist looked up at the

acrobats for a moment as if waiting for a sign. And then she pointed to a pale man in the crowd whose shoulders were hunched

in pain.

The man approached nervously; the Mesmerist stepped forward and sat the man in a chair that had mysteriously appeared, spoke

to him gently and quietly. How the audience strained to hear the words, was it Let yourself rest in my care or was it some humbug incantation? And then the shadowy woman, never taking her eyes from the man, began to move her arms

over and over, just above him: over and over, over and over, long, strong rhythmic strokes, just above the body, never touching,

breathing deeply over and over, her total concentration, her own energy going into the pain of the man and trying to move

it outwards, drawing it out. Was she murmuring to him perhaps? It was not clear. The huge, hot, crowded, stinking, airless

tent was silent: the audience were spell-bound, they could see that the pale man had fallen asleep, saw the strong, smooth

rhythm of the arms of the woman: the arms moving over and over, never touching, over and over.

And at the end (for the Mesmerist had chosen the patient with care, and with the help of her daughter flying above the audience

on a trapeze: they knew they could not cure broken limbs or cancerous growths: they could only help pain): at the end then:

the man awoke, his face cleared, his body straightened; puzzlement, relief, the man looked about himself in surprise. And

as, smiling slightly in disbelief, he was led away from the circus ring, suddenly there were bright shining lights again and

clowns tumbled and the lion roared and acrobats flew and twirled in the suddenly bright air: HOUP-LA! HOUP-LA! they cried as they swung from one trapeze to another and the band played jaunty music and when the audience looked again

to the centre of the ring there was no-one there.

‘Was it a ghost?’ One of the men with gold earrings half-stood, unsure, whispered to his companions, and his voice sounded almost like that

of a child.

‘Sit down, Charlie, you stupid bugger,’ said the tall, wild woman with the trouser braces holding up her skirt, and she leant

across and clouted him, ‘it’s only a trick!’ But Charlie’s face was pale in the lamplight. Under the sound of the brass band

she whispered maliciously in his ear:

The devil damn thee black, thou cream-faced loon!

Where got’st thou that goose look?

but he angrily shrugged her away and spat tobacco.

The charros now rode in human pyramids, dangerous and clever, faster and faster around the ring, calling to each other in Spanish. ‘Cunting

foreigners,’ said Charlie, spitting tobacco again, on to the canvas wall of the tent now. His eyes strayed to where the ghost

had been, but the beautiful, shadowy figure had disappeared.

The New York Tribune wrote:

Newspaper reports reaching us from London have described Cordelia Preston, Mesmerist, as a scandalous and deeply immoral woman

who had – it was alleged – killed the father of her children, Lord Morgan Ellis, heir to the Duke of Llannefydd – who owns,

it would seem, most of Wales. (We do wonder how the Welshmen feel about that.) It is now known that the real murderess was

the wife of Lord Ellis, cousin to Queen Victoria. But as we in our dear and democratic Republic know only too well, those

close to the Monarchy are protected by the Monarchy (in this case until it was impossible to hide the truth when Lady Ellis

tried to kill Cordelia Preston also).

Not all the facts of this matter have come to light – and no doubt Cordelia Preston, acquitted of murder as she has been,

is indeed immoral; scandalous, certainly: it is known that she is now working as a Mesmerist in MR SILAS P SWIFT’S AMAZING CIRCUS here in New York, which speaks for itself. But by chance this newspaper has also ascertained that both Cordelia Preston and

her daughter, Gwenlliam Preston, an acrobat, regularly give their mesmeric services free, with no publicity, to one of the

hospitals in New York which use mesmerism as an anaesthetic during painful operations. They work alongside the world-renowned

Mesmerist Monsieur Alexander Roland, who was trained by Dr Mesmer himself and we have found that they have much success in

helping patients.

Whatever the full story let us re-iterate, as we do very often, God Bless America, the land of the free, and at least let

us be grateful to Cordelia Preston and her daughter for their good works.

Mr Silas P Swift (who had made it his personal business to bring the above-mentioned good works to the attention of the Tribune) rubbed his hands in glee as circus audience figures soared even higher: he had taken a gamble bringing the scandalous Misses

Preston to America and it had paid off beyond his wildest dreams. He was well aware that it had worked so well, at least partly,

because Miss Cordelia Preston (having worked for so many years as an actress) and Miss Gwenlliam Preston (having been brought

up as the daughter of a nobleman) both had a grace and dignity in their bearing that was at odds with the lurid stories surrounding

them. The daughter was very pretty and turning into a most excellent acrobat and tightrope-walker but her mesmeric mother (that startling streak

of white in her dark hair), was hauntingly beautiful: something almost translucent about her face and her cheekbones and her

dark, mysterious eyes.

So twice daily the New York crowds poured in, hundreds and hundreds: thousands, all breathing in the thrilling smells of sawdust

and elephant dung and canvas and wild animals and oil-lamps and mud and excitement. And, twice daily, in a small circus wagon

among the circle of circus wagons at the back of the Big Top, Miss Cordelia Preston, immoral acquitted murderess, put on her

flowing, drifting costume, pulled her long, wafting scarves about her pale face. Occasionally, startling, painful memory clutched

at her and she had to bend over, gasping in shock, and her daughter Gwenlliam would quickly push past the costumes and the

scarves and the shoes and the long balancing poles to reach her mother. For a moment the two would rock gently, holding each

other for comfort. Once, Cordelia found her daughter, always so calm and so sensible, in uncontrollable tears in her shining,

sparkling acrobatic costume in the small, cluttered caravan; quickly she held her tightly, they breathed together, thought

they heard a faraway sound: shshshshshshshshshsh: they thought they heard the sea on a long, long shore and they thought they heard high children’s voices calling: Manon! Morgan!

Manon.

Morgan.

Cordelia’s children, Gwenlliam’s sister and brother.

And then they would finish dressing and leave the little wagon and stand very straight and smile and smile and tease and talk

as they crowded near the African elephant with his big ears and his small, crafty eyes; they crowded together with the clowns and the charros and the fire-eaters and the midgets and the other acrobats at the back of the Big Top as the dangerous lion roared and the

unpredictable elephant suddenly trumpeted loudly and the Mexicans called in Spanish to their horses; and instead of the sound

of the sea Cordelia Preston and her daughter Gwenlliam heard once more the sound of the raucous, excited shouting of the big,

boisterous New York crowds inside, all waiting for the magic of the circus.

The Experimenter was late although actually, at this very moment, he was running as fast as his thin dentist’s legs could

carry him along Cambridge Street towards the Massachusetts General Hospital, clasping an odd-shaped bottle to his chest.

In the amphitheatre there was a loud buzz of impatience in the air: nobody ever kept the eminent and respected Surgeon Dr

John C Warren waiting, so the other eminent surgeons of Boston in the audience tapped their fingers on their canes, while

the medical students whispered excitedly (but reverentially quietly) amongst themselves. Perhaps it was all humbug and they’d

been called here for nothing.

Two impassive figures with dark, paint-cracked eyes observed the proceedings silently. These figures were painted on the outside

of two rather battered Egyptian coffins which stood upright at the back of the stage in the amphitheatre. Whether the ancient

coffins so displayed contained the remnants of dead bodies from long ago and far away was not advertised.

Some of the surgeons nodded to an old Frenchman who sat amongst them: dignified, upright and still: the distinguished Medical Mesmerist, Monsieur Alexander Roland – a foreigner, sure, but at least French not English, and a much respected practitioner

in some of the hospitals in Boston and New York. Monsieur Roland elicited great interest among some of the medical men: for

many years in many countries he had had much success in making painful medical operations bearable to patients using mesmerism

as anaesthesia. Mesmerism as anaesthesia, although many doctors refused to have anything to do with it, was not scorned outright

in these big, new cities; Monsieur Roland had sometimes worked with Dr John C Warren himself, here in Boston. Many of the

surgeons here today, and some of the students with special permissions, had come to watch the Mesmerist more than once – observing

the total concentration of the old Frenchman on the patient. Let yourself rest in my care, he would say gently and then, without taking his eyes from the patient, he would begin the movements with his arms and his

hands: the long, strong, repetitive mesmeric passes just above the patient’s body, never touching, over and over, over and

over, his breathing and the patient’s breathing gradually matching, until the patient – Believe it or not! the observers recounted later – fell into some sort of trance. Then the operation would begin. If the patient stirred as

the operation proceeded, Monsieur Roland would begin again the long, rhythmic passes, over and over, and the patient would

calm, and sleep again. And yet, and yet: in truth there was an uneasiness among many medical men about the whole thing: they

had seen what they had seen, but mesmerism was neither scientific nor explainable. Some of them conceded at least, however,

that it was better than slugs of brandy, and the screaming.

Monsieur Roland had not, today, been asked to mesmerise the patient before the operation, but he was particularly interested in today’s proceedings.

Now, on the stage of the amphitheatre, Dr John C Warren stood beside the patient who was strapped to an operating chair; a

large lump was visible just underneath the patient’s jaw where his shirt lay open and ready. The patient was a New York workman

who was addressed, very formally in this public arena, as Mr Abbot. Mr Abbot had a blank look on his face (but Mr Abbot could

feel his heart beating fast).

Dr John C Warren looked impatiently at his watch.

Along Cambridge Street still, two men ran: one short, one tall. The short man huffed and puffed in a rather alarming manner,

found it difficult to keep up; the tall man, the aforementioned dentist, still held the strange looking bottle in his arms

and his cloak streamed out behind him as he ran up the steps into the main entrance, and then up more stairs to reach the

fourth floor. With the short man heroically not far behind him, the dentist burst into the hospital amphitheatre and, trying

to catch his breath and remove his cloak at the same time, informed the surgeon that he was ready. Both running men had come

straight from the premises of the instrument-maker who had prepared the bottle.

Then Mr Morton, the dentist, (having received a nod of permission from the imperious surgeon) introduced his short-statured,

panting companion to the patient.

‘Mr Abbot: this is Mr Frost,’ said the dentist.

The patient was looking somewhat bewildered as he beheld the dishevelled men and the odd-looking, tube-protruding bottle,

but Mr Frost pumped his hand with enthusiasm.

‘Young fella! I have come along with Mr Morton because I have already had this – ah – treatment.’ Mr Frost took a huge breath

to calm himself from his exertions. ‘Now, young fella: look! Just look!’ In his excitement Mr Frost opened his own mouth wide and pointed, endeavouring to point and

speak simultaneously. ‘See this space? See? See? This was a tooth. The pain was killing me, I felt like killing myself. I

never knew pain like it. But I had this treatment that you’re going to have now and I never felt a thing and no ill effects.

I’ve signed a paper saying so! Go for it young fella, go for it!’

‘Thank you,’ said Mr Abbot, swallowing.

At a sign now from the surgeon a rubber sheet was pulled up towards the patient’s neck. Mr Morton placed a tube, which was

attached to the bottle in his arms, to the lips of Mr Abbot and asked him to breathe in through his mouth.

‘Are you afraid, Mr Abbot?’ asked the surgeon.

The young man shook his head manfully. Mr Abbot trusted Dr John C Warren; things had been explained to him carefully. He breathed

in through his mouth as instructed.

Mr Morton the dentist was afraid, certainly. He had experimented for many months, including upon himself; he knew that if

he failed (which he nevertheless believed he would not) he would be arrested right here in this medical amphitheatre, for

manslaughter. There was perspiration on his forehead as he adjusted the tube and the bottle.

And in the silent, watchful audience Monsieur Alexander Roland understood very well what was being attempted. He had met many

medical students in New York and Boston who indulged in what they merrily called ‘ether frolics’ – inhaling just enough of

the gas to go high! as they told him, like drinking champagne! they told him. Monsieur Roland had met a young man who inhaled another gas, nitrous oxide, who said ecstatically, I laughed and laughed! I felt like the sound of a harp! Monsieur Roland knew experiments had been taking place for years. ‘Take care there,’ was all the old Frenchman ever said, and they assured him they always took care

only to inhale enough of any gas to go high or to feel like a musical sound perhaps, but never enough to let themselves become

unconscious. For fear they would never wake again.

The patient breathed in through the tube that was attached to the bottle, Mr Morton beside him. The painted figures on the

Egyptian coffins remained impassive. After a few minutes had passed (the audience watching so intently, so quietly), the patient

seemed to have fallen asleep. Mr Morton, not taking his eyes from the patient, nodded to the surgeon. The surgeon held his

knife over the rubber sheet.

He spoke to his audience only once, and very briefly. ‘Gentlemen. As you know this is an experiment and we do not exactly

know what the results will be. I am removing this large growth that you see has grown under the patient’s jaw. It is not a

dangerous operation but it is an extremely painful one.’ And then he plunged his knife, but carefully, knowing exactly where

he could cut and where he could not, into the flesh of the man’s neck. Blood spurted out immediately; every person in the

amphitheatre expected a scream. They had all heard, a hundred times, the screams: screams were part of hospital operations.

There was no screaming.

The patient was sewn, the last blood was wiped away and the surgeon had washed his hands in a special bowl. Mr Abbot had mumbled,

he had become agitated at one moment, but he had not woken; now he did not move, and it was difficult from the audience to

see if he was even breathing. The silence in the amphitheatre was now like a shout: Is he dead? Not a soul stirred, not a cough. Perspiration poured now from the forehead of Mr Morton the dentist; finally he took a handkerchief

from his jacket pocket to wipe it away, still without taking his eyes off the man in the operating chair for a single second.

He had understood how long the operation would take; he had measured the dose exactly; it was the purest ether that could

be obtained. He put his handkerchief away again, never taking his eyes from the sleeping man.

‘Mr Abbot,’ said Mr Morton softly to the patient. ‘Mr Abbot.’

An arm moved.

And then, at last, Mr Abbot opened his eyes. (Mr Morton said later that he almost expired at this moment, from relief.)

The surgeon bent down.

‘Are you all right, Mr Abbot?’ There was a slight nod.

‘Did you feel pain, Mr Abbot?’

They saw the patient moving his lips, wetting them with his tongue, trying to speak. An assistant brought a small glass of

water. ‘No, sir. No pain.’

Dr John C Warren, nearly seventy years old, piercing eyes and shaggy eyebrows, one of the most respected surgeons in Boston,

bent again towards his patient, stared at the large wound and at the face o

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...