Chapter 1

Never hire a nosy plumber.

They ask questions all the time. This means you don't have a chance to ask questions yourself. Important questions, such as "Why is it leaking?" or "Does it need to be replaced?"

Instead, you're answering the plumber's questions. Meaningless questions, such as, "Wasn't the family who lived in this house mixed up in some crime, way back sometime?"

A nosy plumber will drive you crazy. I was convinced of this as "Digger" Brown tapped on pipes in the basement ceiling of the Bailey house.

The Bailey house represented a new business enterprise for my husband, Joe Woodyard, and my uncle, Hogan Jones. Flipping. Not hamburgers. The house.

Joe and Hogan wanted to buy a house-one that happened to be near the one Joe and I lived in-remodel and update it, then sell it at a profit. I wasn't enthusiastic about the project, but I had been assigned a job anyway. I was showing the potential plumber around so he could give us an estimate.

Digger was Joe and Hogan's first choice of plumber. I couldn't figure out if they favored his work because the guy was a top-notch plumber or if they liked him because of friendliness for his father, whose business Digger had taken over after an older son failed to follow the family occupation. As far as I could tell, Digger was like any other plumber-sort of grimy, with shaggy, light brown hair sticking out from under his baseball-style cap. He wasn't tall, but his arms bulged with muscles. At least he wore overalls, not droopy work pants that showed the proverbial "plumber's crack."

Digger's "way back sometime" question brought up a topic I didn't want to discuss. After all, Digger had lived in Warner Pier a lot longer than I had, and it was a town of only twenty-five hundred. He ought to know more about the Bailey house and the Bailey family than I did.

So I dodged the question.

"I don't know much about the house's history," I said. "And I didn't know the Baileys very well, but my aunt says they were wonderful neighbors. I'm afraid that since they'd both been ill during the past few years, they hadn't maintained the place too well. The two kids are selling it as is."

There. Maybe that would get Digger back on the topic. Which was the house's plumbing, not its history.

Instead, it led to a different nosy question. "I guess these houses along Lake Shore Drive are selling for a bunch of money. What are you planning to ask when you flip it?"

I gave a deep, annoyed sigh and hoped Digger heard it. "That depends on how much it costs for the renovations," I said. "Such as the plumbing. We're relying on you to tell us that."

Digger grunted as he bounced the beam of his flashlight around the concrete walls and floor of the unfinished basement. The overhead light was on, but its bulb was dim, and the corners of the room were murky.

The house had been built in the mid-'50s, according to Joe and Hogan. Genuine "mid-century modern," they called it. It was one story, with an open floor plan. It had an attached carport on its north side, a wall of glass in the living room, and exposed rafters in the kitchen. Those rafters were ornamental, not utilitarian like the rafters Digger and I were looking at in the basement. All the house lacked was a flat roof; Joe said it might have had one originally, but the lake-effect snows of the Lake Michigan shore had apparently proved such a roof impractical, and at some point a slanted one had been installed.

"I'll do some figuring before I make an estimate," Digger said. "That is, if you want a firm price."

"Naturally," I said. Talk about stating the obvious. What else would we want? A shaky price?

I resisted the temptation to hit the guy. Or at least to snarl at him.

I was ready to hit anybody these days, and it wasn't Digger's fault. I wasn't really mad at him; I was mad at the two most important men in my life, Joe and Hogan.

I'm Lee Woodyard, a Texas gal who wound up living "up North," in a resort town on Lake Michigan. This happened because I became business manager for my aunt, an expert chocolatier who owned a shop specializing in luxury bonbons and truffles-the kind of chocolate that appeals to the rich folks who live in or who visit a resort like Warner Pier, Michigan.

Five years earlier I had moved to Warner Pier-my mother's hometown and the most picturesque resort on Lake Michigan. I had planned to stay only a couple of years, but to my surprise, I had found myself putting down roots. I had even fallen in love with a great guy who was a native Michiganian. Joe Woodyard and I had been married three years and now lived in a hundred-year-old house built by my great-grandfather.

We got the family home when my aunt, Nettie TenHuis, remarried after several years of widowhood-linking up with another great guy named Hogan Jones. Hogan just happened to be chief of police for our town, and he and Joe were friends as well as in-laws. Hogan and Aunt Nettie moved into a house Hogan owned, and they passed Aunt Nettie's house on to us.

This was all fine until Joe and Hogan had the brilliant idea of flipping a house. Both had experience with building projects, and they thought they could have fun and make some money. When the house down the lane from Joe and me went on the market, they declared it the perfect opportunity and put in an offer. Aunt Nettie, an eternal optimist, thought it was a lovely plan. Everybody was happy but me. I hated the idea.

Joe and I had to mortgage a debt-free house to raise our share of the money. Everything in my soul, character, and personality yelled, "Wait a minute!"

I made it clear to Joe, Hogan, and Aunt Nettie that I hated the idea. They all claimed to understand why I felt that way. But they went ahead anyway, dragging me into the deal with them. And I hated the idea even more after another bidder appeared. Spud Dirk, a small-time developer in Warner Pier, said he was going to come up with a better bid for the property. Spud's idea was to build a complex of vacation apartments, a proposal that did not thrill Joe and me. We liked our neighborhood the way it was, a rural area abutting a neglected orchard that Spud already owned. I didn't see why Spud Dirk couldn't just sell his orchard, take the profit, and leave our neighborhood in its current state.

But the Bailey kids were holding to our handshake deal, telling Spud Dirk they'd already promised to sell to us. This thrilled Joe and Hogan, and even Aunt Nettie. It infuriated Spud, apparently, since he threatened to punch Joe out over it. When I heard about that, Joe said, "Spud talks a lot." The two of them never exchanged anything but words about the house.

So the four of us were in the process of buying the Bailey house, and the Bailey kids were allowing us to go into the house and get ready for the remodeling even before the papers were signed.

Everything was great, except that I hadn't slept for a week.

"Now, Lee," Joe had said, "I promise. Hogan and I will handle everything. You will simply keep on with your usual activities. You won't have to pound a nail or pick a paint color."

"I'm not afraid of the work," I said. "I'm afraid to borrow money."

"But the potential for making a big profit by flipping the Bailey house is just lying there. Between us, Hogan and I have enough experience-"

"No! I know y'all can remodel the house, Joe! You just can't do it without borrowing money. And our only collarbone-I mean, collateral! Our only collateral is our own home."

I'm one of those people who get their words mixed up-such as by swapping "collarbone" and "collateral." Luckily, people close to me, such as my husband, mostly ignore my twisted tongue.

I pushed right on with my argument. "And you know how I hate to borrow money."

Joe went right on, too. "Lee, you're an accountant and an excellent businesswoman. You're aware that sometimes you have to borrow money to make money."

"No," I said.

I was falling back on my favorite method of arguing. Just state your position. Don't bring up a lot of reasons. When your opponent can tear down arguments one at a time, you lose. If you simply stick to your decision, you can win. So I kept repeating, "No."

Joe was the one arguing. "If I could make a nice chunk of money," he said, "I could put it toward my debt."

That's where he had me. Mortgage and all.

Joe's first marriage-ending in a divorce and the subsequent death of his ex-wife-had left him deeply in debt. He now worked two jobs-one running a boat-restoration business and one as an attorney-to keep even. Yes, a large infusion of cash would be a major help to our personal finances.

I had finally agreed to go along with flipping the house. But I refused to be gracious about it.

And despite all Joe's promises that I wouldn't have to help with the project, there I was, showing the plumber the house so we could get an estimate on that part of the construction. And doing it at a time when I should be at work. My own work. Selling chocolate. I glanced at my watch. I had an appointment at four o'clock, this one to confer on a community project. Was I going to be late?

I had already been late meeting Digger, leaving him to twiddle his thumbs in the carport until I could get there. Or he should have been twiddling his thumbs.

Actually he could have gotten in on his own, or so he said. He'd already told me that his brother knew the Baileys' son, Tad, and that all the "gang" of guys they ran around with in high school used this basement as a hangout.

"Mrs. Bailey left a key hidden by the outside door for them," Digger said. "She used to lock the door at the top of the stairs instead. Of course, I was a kid brother. I wasn't supposed to come in that way, but I knew about it."

Digger had assured me that everybody in rural Michigan hid a key near their cellar door. "I remembered where this one was because I knew the Baileys when I was a kid," he said. "Mr. Bailey kept a key on a rafter in the carport in those days, and I'll bet it's still there."

"That so?" I sighed. I didn't want to hear about the Baileys' basement door key.

The whole afternoon was leaving me a bit exasperated anyway. I told myself that as soon as I was at my desk, I was going to comfort myself with a caramel shark. Flavored, oddly enough, with sea salt.

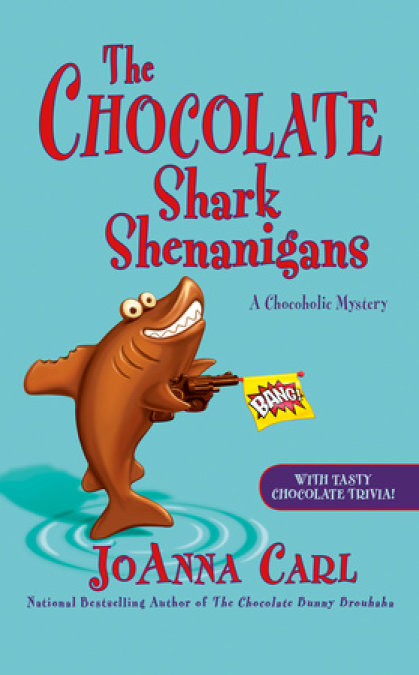

Every year our little resort, Warner Pier, picks a theme for the summer's tourism projects and advertising. This year it had been "Lake Michigan-Fisherman's Paradise." Decorations and special events had all focused on native fish.

And, of course, the native fish of Lake Michigan do not include sharks. But the plan had worked. We had sold bunches-schools-of fishy chocolates, all flavored with hints of salt.

When Aunt Nettie suggested that we create and sell chocolate sharks in several flavors, all using a smidgeon of sea salt to bring out their sweetness, I thought she must have been having nightmares. But when she made some samples, I was won over from the first bite.

Our promotional material described my favorite flavor as having "a soft caramel center enrobed with milk chocolate, with bits of sea salt embellishing the top."

I tried to listen to Digger, but in my imagination I could taste that soft caramel. It tasted delicious without sticking to my teeth.

Digger was rattling on. "I kinda like these old basements," he said. "My grandmother's house had a cellar door like this one does. Does your house, over there across the road, have one?"

"No. We don't have an outside door into the basement. But we have a Michigan basement."

"Good old sand floors?"

"Right."

"Well, either kind of basement looks homier if it has a big bag of potatoes propped in the corner. Does the one over at your house have these thick walls?"

"Not as thick as these. About a foot."

"Not much good for storage, then. Not like this one."

The Bailey house had concrete walls about two feet thick. Since the rafters were open, there were lots of niches available for storing stuff. Old fruit jars, rarely used cleaning materials, and odd gadgets proliferated in these rooms, filling the space on the tops of the walls. Joe, Hogan, Aunt Nettie, and I had spent a lot of time clearing this one out.

At least Digger's questions had stopped for the moment. He was quiet as he picked up the ladder he had brought along and propped it against the wall, settling the legs firmly on the floor.

"These pipes are for the bathroom," he said. "I hope they haven't leaked over the years."

"That's why we called you in, Digger. You're supposed to tell us if they have to be replaced."

"When was this house built? In the 1950s?"

"That's right."

I deliberately kept my answer short. I didn't want to encourage Digger to come up with any more questions, time-consuming questions. I peeked at my watch. Three o'clock. Darn! I ought to be at the office.

Digger's voice brought me back to the current problem. "I guess the Baileys left this stuff here."

"Stuff? What stuff? We thought we cleared everything out."

Digger used his flashlight to point at some rags tucked away on the niche that topped the concrete wall.

"You shouldn't leave this here," he said. "It's bound to attract mice."

"Gross! Pull it out, Digger. Let's get that out of here. There are some trash sacks in the kitchen." I headed for the wooden steps that led upstairs.

"There's something wrapped up in them," Digger said.

"What is it?" I turned around, stopping halfway up the stairs to look at him. As I watched, he juggled the rags around, grabbing at the bundle. He made a final snatch, but missed, and the wad of rags landed at the foot of his ladder.

I hadn't expected it to make such a loud noise when it hit.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved