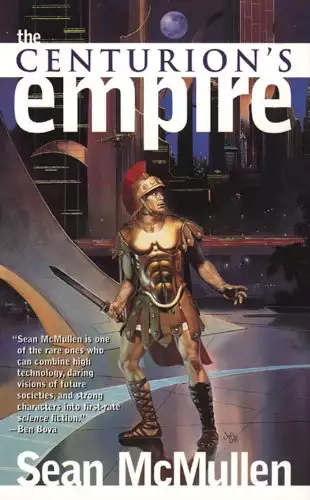

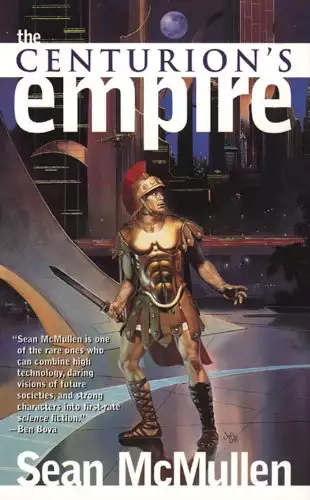

The Centurion's Empire

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

In the year that Mount Vesuvius destroyed Pompeii, the Roman Centurion Vitellan set off for the twenty-first century as Imperial Rome's last human-powered time machine. He killed an unfaithful lover by just letting her grow old, but her hate pursued him across seven centuries. In 1358 he stood with a few dozen knights against an army of nine thousand to defend the life of a beautiful countess...and earned a love that would conquer death.

Now Vitellan has awakened in the twenty-first century, a bewildered fugitive, betrayed and hunted in a world where minds and bodies are swapped and memories are bought, sold, and read like books. But worst of all, a deadly enemy from the fourteenth century is still very much alive--and closing in.

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: May 1, 1999

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Centurion's Empire

Sean Mcmullen

1

Venenum immortale

Nusquam, the European Alps: 17 December 71, Anno Domini

Rome was near the height of its power in the second year of Vespasian's reign as emperor, and nobody would have suspected that the Empire's fate hung by the life of a five-hundred-and-eighty-year-old Etruscan. Celcinius lay with his ears and nostrils sealed with beeswax plugs, and his mouth bound shut. His body was frozen solid in a block of ice at the bottom of a shaft two hundred feet deep.

Regulus held his olive oil lamp high as he entered the Frigidarium Glaciale. He shivered, even dressed as he was in a coat of quilted Chinese silk and goosedown. The sheepskin lining of his hobnailed clogs did no better to keep out the cold, and the fur of his hood and collar was crusted with frost from his own breath. Wheezing loudly after the long trek down through corridors cut through solid ice, he paused for a moment.

"There'd be something wrong were it not so damn cold," he panted to himself as he leaned against the wall, watching his words become puffs of golden fog in the lamplight.

The Frigidarium Glaciale was a single corridor cut into the ice. It stretched away into blackness, as straight and level as a Roman road. On the walls on either side of him were rows of bronze panels, each two feet by seven and inscribed with names and dates. After a minute Regulus reluctantly heaved himself into motion again, shuffling down the corridor and leaning heavily on a staff that bore the Temporian crest of a winged eye. Its other end was tipped with a spike, so that it would not slip on the ice of the floor.

He paused again by a panel marked with his own name and bearing twenty-six pairs of dates. There was something strangely alluring about this cell cut into the ice, where he had spent 360 of the 437 years since his birth. Following hisown private ritual he knocked out the pins securing the top of the panel to retaining bolts set into the ice, then levered it down with his staff. The hinges creaked reluctantly, shedding a frosty crust. Behind it was an empty space six feet long and two feet deep.

Regulus stared into the little chamber, holding the lamp up and running his gloved hand along the surface of the ice. He had been in there when Plato had died, and for the whole of Alexander the Great's short but remarkable career. Regulus had, of course, been awake to attend the Temporians' Grand Council, the single time when all his fellow Temporians had been awake together. That was when they had decided to abandon their Etruscan heritage and support Rome. The Punic Wars and rapid expansion of Roman power and influence had followed, and Regulus had been awake to earn scars in the fighting against Hannibal. There had been more years in the ice after that, until he had been revived in time to cross the Rubicon with Julius Caesar. That time he had stayed awake for two decades, until after the defeat of Antony and Cleopatra. He had returned to the ice again by the time Christ was born.

The old man was secretly a little claustrophobic, and disliked both being in the Frigidarium Glaciale and the prospect of some day returning to his assigned cell there. He heaved the bronze panel back into place. "Never again," he promised himself as he scanned the dates in the dancing lamplight, then he turned and shuffled farther down the corridor of the Frigidarium Glaciale like a short, arthritic bear.

At a vacant cell he took a metal tag from his robes, slid it into a bracket and sealed it into place. He studied the entry for a moment before moving on.

"Vitellan Bavalius, eh?" he chuckled softly to the name on the panel. "You're the lad who survived five days in a cold sea after that troopship sank last September. You don't know about us yet, lad, but you are destined to join us and sleep in this hole. We're watching you now, and you are very promising. You're a strong, natural leader, and you have great resistance to the cold. Those are perfect qualifications to become a Temporian and live for a thousand years."

Regulus patted the tag with Vitellan's name like a teacher encouraging a good student, then walked down to the very end of the Frigidarium Glaciale. The panel bearing Celcinius' name was alone in the wall at the end of the corridor. Regulus turned and glanced behind him, more through habit than paranoia. The entrance had now faded into blackness, but the corridor was empty as far as he could see. He released the pins and pried the panel out to reveal a block of rammed snow, from which emerged leather straps bound with a wax seal. He allowed himself a little smile: the imprint in the seal was his own: 217 years earlier he had been acting as the Frigidarium Glaciale's Master of the Ice for the first time when Celcinius had returned to the ice. Satisfied, he swung the plate back and checked the dates inscribed in it. Celcinius was ninety-four in terms of years awake. That was bad. It would be a difficult revival.

Regulus slowly made his way back down the length of the Frigidarium Glaciale, past the 370 other bronze plates, and stopped at the thick, metal-bound oak door. With a twinge of shame he realized that he had not checked the reading in the lock when he had entered. "Memory's going too," he muttered, taking a stylus and wax tablet from the folds of his heavy robes and peering through a slit in the lock's housing. Three numerals were visible, and Regulus noted them. He was about to pull the door shut when he realized that he had not locked the door behind him while he was inside the Frigidarium Glaciale. "Lucky nobody's here to see all this," he said, pulling the door shut. Taking an iron key nearly a foot in length he locked the door, unlocked it, then locked it again. The lock's mechanism was the most advanced in existence, and had been installed only five years earlier. It incorporated a counter-wheel that recorded the number of openings and closings, and could not be reset. He noted down the second--and now correct--reading.

"If my memory's as bad as that I'll not get out alive," he muttered as he pulled his fur-lined mittens back on.

The Frigidarium Glaciale was not located in a glacier, but was cut into unmoving, stable ice in a deep ravine between two mountain peaks. Regulus cautiously walked down aflight of steps carved out of the ice and along another passage. At the bottom was a door, in fact every twenty feet there was another door to seal in the cold air. There were no guards down here, but it was still a dangerous place for intruders. One door opened onto a walkway above a deep pit with long, sharp spikes at the bottom. The walkway was designed to tip unwary visitors off if they did not reset a group of levers in the right sequence at the halfway point. Beyond this was a vault of ice blocks that would collapse unless a lever back at the previous door was moved to the correct notch first. Finally there was a cage of metal bars, and beside it three wheels with numbers engraved on the rims. Set the wrong code on the wheels and the lower passage would be automatically flooded with water piped from a heated cistern two hundred feet above. The right code alerted a slave in the palace to start his horse turning a windlass to raise the elevator cage. Regulus entered the cage and pulled the door shut. He reached back out through the bars and set the wheels to the correct code.

After an interval that never failed to unnerve him the cage jerked slightly, then began to move upward. He leaned back against the bars and sighed a long plume of condensed breath. Perhaps his memory was not so bad after all, perhaps his lapses in the actual Frigidarium Glaciale had only occurred because his life had not been at stake down there. The olive oil lamplight showed stratified layers in the ice and occasional stones as he made the slow journey upward. He had a name for every embedded stone that he passed, he had made the trip hundreds of times. All that seemed to change was the intensity of the cold. For the last few feet the shaft was lined with marble blocks.

The cage emerged into a torchlit stone chamber, then stopped. A woman in her late fifties was waiting for Regulus, shivering within several layers of pine marten fur. She unlatched the cage door while the slave in charge of the windlass threw the anchor bolts at the base of the cage. Regulus was trembling almost convulsively as she led him to a little alcove that was heated by air piped from a distant furnace. The warmth slowly eased his distress.

"I told you to take an assistant," she said as she pouredhim a cup of warm, spiced wine from a silver flask on an oil-burner stand.

"The rules are the rules," he replied between chattering teeth.

"Do you know how long you were down there?"

He ignored the question. "Well Doria, the seal on Celcinius' body is intact," he reported, then gulped a mouthful of wine. "Everything is as it was during my previous inspection. I can authorize his release if the Adjudicators vote for it."

"He was eighty-nine last time he was revived," said Doria, putting a pan of wax on the oil-burner. "According to the Revival Ledger he hovered near death for six days. I'll not vote for revival. Not just now, anyway."

"The last unpaired date on his panel shows that he was ninety-four at the time of his last freezing."

"I know, I know. It is in my own records." Doria closed her eyes and took a deep breath. "Surely we can make our own decisions by now. We don't need his sanction."

"Perhaps not, but the Adjudicators are still calling for his sanction," Regulus said as he rubbed the circulation back into his hands. "That's why they want him revived."

"If he dies, what then?" asked Doria. -

"If he dies we have lost our founder," he replied with resignation.

"Precisely," she said with some vehemence, now leaning forward and tapping the heated stone bench. "We lose our greatest unifying symbol."

"Doria, please--there are complex issues here. The Adjudicators cannot be forced to rely on their own authority and judgment when they rule on Vespasian making himself Emperor."

She sat back, shaking her dyed black curls. "With Celcinius frozen, at least we still have our founder symbolically alive. The Adjudicators must learn to make their own decisions without a nod from him."

Regulus slowly picked up his cup and took another sip of wine. "I'm confused. Would you have Celcinius frozen forever? What is so bad about such an old man's death?"

Doria sat watching the condensation of her own breath as she considered her reply.

"It is bad for the woman in charge of the revival team that fails to restore Celcinius to life, and I am that woman," she said slowly and clearly, then closed her eyes.

"So, a hidden agenda."

"In the ice he is at least not dead, but if we try to revive him he will almost certainly die. Why bother, why not leave him alone? What is your hidden agenda, Regulus?"

The slave appeared at the door of the alcove, bowed and entered.

"We shall continue this later," said Regulus with some relief.

The slave reported that the cage was secure for his inspection. Regulus grumbled, but got to his feet, pulling himself up hand over hand with his staff. The slave bowed again and backed out of the alcove, and Doria followed them with the pan of hot wax. Regulus gave the cage a cursory check, tapping bars, pins, and gears with his staff, then he gestured to Doria. With a practiced flourish she poured the wax over the master lock pin of the windlass, and after a moment Regulus pressed his ring seal into the soft, warm wax. The heat was welcome on his chilled fingers, and he withdrew the ring with reluctance.

"Did you attach the tag plate for young Vitellan Bavalius?" Doria asked as they walked through the blackstone access corridor.

"Yes, yes, yes, I'm not senile yet. When is he due to be initiated?"

"In a few months. He was to be sent to Egypt, but I had him sent instead to the Furtivus Legion that guards the approaches to this palace. He is stationed in Primus Fort, and Centurion Namatinus has been sending me reports on him--in fact he is due to be part of the escort for our next mule caravan of supplies."

"How has he reacted to being in a secret legion?"

"Extremely well. He is our first Christian recruit, did you know that? The Christians have a strong sense of discipline, dedication, and duty, and they teach their children to keep secrets almost as soon as they can talk. They could well become a prime source of new blood for us Temporians. Vitellan is certainly a model recruit."

Regulus spat and cursed. "Damn cruel, it is, taking a boy of seventeen and freezing him for fifty years. It's killing his friends and family for him, even though they will live out their lives unharmed."

"But he must have all his personal ties severed while he is young and flexible, Regulus. He must become accustomed to living as we do. It may be a sharp wrench for him, but the rewards are great. Our reports certainly indicate that he has the rare combination of qualities that makes a good Temporian."

"He may not want to join us, once he has been told of our existence. He may have a girl somewhere."

"Then he will be killed," said Doria simply. "You know that as well as I do."

They emerged into the palace, but Regulus insisted on going out onto a balcony at once. The winter sky was blue and clear, although the lower part of the mountain was shrouded by mist. The air was still and crisply cold. He breathed deeply, savoring the pure, fresh air and swearing to himself that he would never again drink the Venenum Immortale and sleep frozen in the Frigidarium Glaciale.

An Alpine Trail: 17 December 71, Anno Domini

Gallus was thankful that this was the season's last trek through the Alps to feed the gods. Already the snow was deep, and within a few weeks his mules would find it impossible. An unseasonably heavy fall could easily happen as early as tomorrow, he reminded himself. Vitellan rode the last mule in the line, alert and keenly observing everything. He was young and enthusiastic, like all the other Roman legionaries that had been assigned to escort Gallus' mules over the years. In the spring Vitellan would be transferred somewhere else, but Gallus could look forward to many more years of hauling grain, oil, firewood, and luxuries through the mountains, and leaving it all on a huge altar for the gods to take. Why are my assistants transferred so quickly yet I remain here, Gallus wondered. Have I failed some unspoken test of the Furtivus Legion?

In all his years of travel Gallus had never seen the gods.Their altar was at the base of a sheer cliff whose top was generally obscured by mist. Occasionally a muleteer-legionary would stay back and hide among the rocks to see what took the piles of sacks, bales, amphorae, and firewood from the altar, but the story was always the same. An enormous hand would reach down and snatch away the piles during the night. Some muleteers who stayed back were never seen again.

Gallus was steady and conservative in his work. He displayed no curiosity about the gods, did as he was ordered, and was always punctual. It was a hard but secure life, as there were no bandits to fear in such a remote part of the Alps. Later that day they would meet with the main convoy of seventy mules, and from there it was another two days to the altar.

An arrow thudded into his chest. Gallus stiffened, then toppled across the neck of his mule. His thick butt-leather breastplate had taken most of the impact so that the point barely scratched his skin, but Gallus was not about to let anyone know that. Behind him came shouts and curses from Vitellan and their attackers: "He's hiding!" and "Mind the mule!" The animals were in a panic already, but the snow and their leads prevented them from bolting.

More shouts echoed through the mountains, mingled with the clang of blades. Vitellan was fighting from behind his mule. The mules had value, and the bandits would not risk injuring them. Gallus listened to the voices. Four or five of them. "Grab the lead mule!" That was his cue. Footsteps came crunching through the snow, lungs wheezed that were unaccustomed to the thin alpine air. "Off with ye," said a voice with the intonations of a pleb from the lowlands cities, but as the bandit tried to push Gallus from the mule the old legionary suddenly reached forward with an unthreatening, fluid, even gentle gesture and plunged a dagger into his throat.

Now Gallus slipped from the mule and looked back, the arrow still protruding from his chest. Vitellan had sent one of the bandits staggering away clutching his side and was engaging the other two. Two down. No more than five in total, including one hidden archer. Gallus started back, shelteringbehind each mule in turn. An arrow struck a grain sack, fired from the rocks to the side of him. Good, good, nearly past the archer, Gallus thought.

"Keep 'em fighting, Vitellan, they'll tire before we do," Gallus called, but even as he spoke he realized that he was tiring fast himself. With dagger and gladius he engaged a bandit who was working his way behind Vitellan. The man was skilled with his weapons, but was hampered by the thin air, cold, and snow. Another arrow hit Gallus' breastplate, but its point barely pierced his flesh. Somewhere to one side a bandit cursed with pain as Vitellan's blade slipped past his guard.

Gallus was by now all too aware of a lethargy sweeping over him. He tried ineffectually to parry a curving snap and the blade thudded into the side of his head, cutting flesh and bone. Gallus collapsed to the snow, but felt as if he was still falling and falling and falling. In the distance Vitellan screamed, an echoing, fading scream.

Lars scrambled down from his vantage, brandishing his bow and cursing with fury.

"One dead and two wounded!" he shouted. "And from fighting only two legionaries."

"Tough buggers," gasped Vespus, who was draped across a mule's packs.

"You're veterans of the arena."

"Gladiators don't have thin air ... and snow. These legionaries ... are stationed here. They're used to it."

The mules were standing still, but were frightened and restless. Lars began to strip Gallus' body.

"Butt leather," exclaimed Vespus. "The old fox wore butt leather under his furs."

"It slowed my arrows and scraped most of the poison from them. No wonder he took a while to die."

Lars tramped over to the edge of a steep drop where the two other bandits sat resting and binding their wounds.

"The other one tried to run, and lost his footing at the edge of the cliff," one of them explained.

"Yes, I saw it all," Lars said sharply. "Now climb down and get his clothes."

The man groaned with dismay. "Master Lars, that's a fearsome drop and we've been badly cut about."

"Do as I say!"

"If we do, it'll take all afternoon. That will make us miss the rendezvous wi' the main caravan in a few days' time. D'ye know the way to the altar without them?"

Lars glared at the black smudge that was Vitellan, half buried and motionless in a snowdrift far below, then tramped back to the mules. "Here's his cloak and a spare tunic," he said, flinging a bundle to the wounded men. "Strip the clothing from this dead one, and that will have to do. What are your injuries?"

"Three broken ribs and a long cut," said one.

"Deep thrust to the leg, but I can ride," said the other.

"Then bind yourselves up and dress as the legionaries. Try to fight like 'em too, if needs be. You will be Vitellan, and you will be Clavius, a new recruit. When you get to the rendezvous tell the trailmaster that Gallus fell ill."

"True enough," laughed the new Vitellan, then winced at the pain from his ribs.

They threw the bodies of Gallus and the dead bandit down after Vitellan, then unloaded two of the mules and flung the sacks over the edge as well. After an hour of frantic labor in the thin air, the line of six mules moved on again. The animals were nervy and cantankerous at being driven by unfamiliar masters. Lars and Vespus rode in padded sacks marked as woollen cloth. The sun was already down when they reached the rendezvous. They found it only because the mules knew the way on their own.

Vitellan revived soon after his fall, but he had the sense not to move until after dark. Deep snow had broken his fall, and beyond a few minor gashes and sprains he was unwounded. He examined the two bodies nearby. Gallus had been stripped, but the dead bandit's body was fully clothed. Vitellan was surprised to find sacks from two mule packs lying in the snow as well. There was costly cloth, fine smoked fish, dried beef and even a small amphora of very expensive wine. With a prayer of thanks to the God of the Christians he crawled under a rock shelter in the face of the cliff, wrapped himself in the bolts of cloth and settled down to a more than satisfactory meal to recover from his ordeal.

"Yet again the cold has saved me," he whispered to himselfas he gazed out at the starlit snowdrift that had preserved his life.

The next morning it took five hours for Vitellan to climb back up to the trail with a makeshift pack of provisions on his back. At the site of the ambush there was nothing of any use left behind. He considered his options as he examined the mule tracks. The bandits had continued along the trail right after the ambush, and there were at least four of them. Even if he could catch up with them there was no point in a lone man attacking four. Besides, they had stolen no more than supplies for some temple deep in the mountains where offerings were made to the old gods. As a Christian, Vitellan thus felt no sense of outrage or sacrilege. He would walk back to Primus Fort and alert the centurion. A couple of dozen legionaries would be sent to hunt the bandits down.

Vitellan started walking back along the trail. At first he estimated that he could reach the fort in three days or less at a brisk pace, and provided that no more snow fell. The distance was no problem, as he had plenty of food and warm bedding for the trek. Presently he slowed his pace. Aware that death from bandits, snowslides, or just sheer cold was never far away, Vitellan decided to travel more slowly and cautiously. He had been badly shaken by Gallus' lonely death and his own narrow escape. He had not known the older legionary long enough to be a real friend, but his death nevertheless left a distinct hole in Vitellan's sense of reality. As it turned out his trek was without incident, but he took five days to reach the fort. Had he hastened and made it in three, the course of history would have been changed.

The Temporian palace of Nusquam had been built between two mountain peaks, and the original building was over four centuries old. The walls were carved out of the mountain itself, while the buildings of the palace rose in terraces up the side of one peak. The design was such that it was not obvious to anyone looking up from below. It was divided into the Upper Palace, where thirty Temporians lived, and the Lower, which housed seventy slaves and guards. Three hundred frozen Temporians lay far below in the Frigidarium Glaciale, and the other forty Temporians were scatteredthroughout the Roman Empire, attending to its business and expanding their control.

Since their early Etruscan beginnings the Temporians had remained a remarkably stable group. Celcinius had been a physician in an Etruscan city north of the Po River. He had been experimenting with medical formulations when he had stumbled across what he named the Venenum Immortale, the Poison of Immortality. Animals treated with it could be frozen, then thawed and brought back to life. If given an antidote straightaway they would thrive and live normally. At first Celcinius thought of the Venenum as an interesting curiosity, but soon after he perfected the dangerous oil's use he discovered a most important application.

He had a nephew named Marcoral who was a brilliant young military commander. Marcoral had fallen in love with a noble's wife, and the two had been sentenced to death when the liaison had been discovered. Celcinius had "executed" them with his potion, then he had frozen their bodies in rammed snow and had them buried in a perennial ice-field high in the nearby mountains. Nine years later, when his city came under attack, he brought the couple back to life under the guise of sorcery and magic. The unnaturally young-looking lovers seemed to have been deified, and rumors spread among the troops that Marcoral was now invincible. The city's defenders swarmed out behind him to annihilate the enemy in a brief, one-sided battle.

The broader, strategic significance of what he had done did not escape Celcinius. What good was a brilliant commander in times of peace? Why should the best engineers and masons be idle during the quiet decades of a city's development? Could the best administrators be saved for times of crisis, rather than wasting their years through periods of tranquillity?

Celcinius had a fortified villa built on a mountain in the Alps. Beneath it was a blind ravine filled with ice, and unlike the unstable, fracturing, moving glaciers, the lower layers of this ice were stable and unmoving. It was a perfect site for a permanent, stable ice chamber. He set his apprentices to work, developing and refining his original formulation,then he lay frozen himself for three decades to await results that he could not have normally expected to see until he was an old man. Once the Venenum Immortale had been refined and perfected, Celcinius had been revived. He immediately had all his apprentices killed, and after that its secret was never again known to any more than three Temporian men at any one time.

Other talented men and women began to join Celcinius, and gradually the power and wealth of this strange oligarchy grew. His villa slowly expanded until it became the palace Nusquam. As the centuries passed, social structures grew and evolved among the Temporians--as they began to call themselves. The impressive and secret pool of talent grew continually in influence, yet they never allowed themselves to become kings. They always worked as lesser leaders, and from behind the scenes. When the continuity of Temporian administration was added to the vitality of the emerging city-state of Rome, the seeds of a mighty empire were laid.

The keystone of Temporian power was the Venenum Immortale, and its key ingredients were derived from the bodies of snow-dwelling insects. These were gathered by ordinary farmers and their slaves, along with the other harvests that they took from the land. The makers of perfumes, medicines, and the like already paid good silver for bags of odd roots, insects, and dried animal glands, so the collection of the insects for the Venenum Immortale went unnoticed alongside this trade. Every five years there would be enough to brew up several jars of the Venenum, and one of the three Venenum Masters would be revived to do the work.

Experience was never lost to the Temporians, and they learned to disguise their own existence to the point of near-invisibility. Some senior Romans knew that "gods" walked among them, strange and brilliant individuals who only appeared when particular types of demanding work needed to be done. These people did not seem to age at all. They were known as the Eternal Ones, the Gods of Romulus, the Sons of Romulus, and the Immortal Scribes, and it was also known that exceptionally talented mortals were sometimes recruited to their ranks. Outsiders, even if they were kingsor emperors, always died or disappeared if their investigations of the Temporians were too persistent. Julius Caesar, Caligula, and Nero had that in common at least.

Nusquam: 17 December 71, Anno Domini

Doria was the current Mistress of Revival. Just as Regulus oversaw the freezing process and maintenance of the Frigidarium, she was in charge of the delicate and dangerous process of restoring the frozen Temporians to life. Regulus lay on a couch in her comfortably heated chambers, recovering from the ordeal of his inspection tour. He contemplated the frescoes on three of the walls, which ranged in subject from battles with Hannibal to erotic frolics involving naked Temporians in Arcadian settings. Regulus was depicted too, standing beside Caesar on the banks of the Rubicon in the most recent scene to be added to the frescoes.

The fourth wall was lined with shelves of colored glass jars, most containing oils and powders. There was also a large collection of scrolls and various medical instruments. The women who conducted the revivals documented their skills and experience in considerable detail, quite the opposite of the Venenum Masters. Doria sat at a writing desk, working her way through a scroll and frowning.

"I can't think of anything more dangerous," she said after she had been writing for some time. "Celcinius is too old, he survived that last revival through sheer luck."

"Who was in charge of that revival?"

"Rhea. She is the leader of Prima Decuria for this revival too."

"Well, that's the best you can do."

"The whole thing is still dangerous. The question remains, but nobody will answer it: why revive him? Celcinius is worth more to the Adjudicators frozen than revived. He's our symbol, and a very potent symbol."

Regulus turned sadly from her and looked to a fresco of Celcinius experimenting with chemicals in his ancient Etruscan villa. He had been handsome and dynamic when younger.

"It seems wrong that he can be allowed to neither live nor die," he said. "It's so undignified for one so great."

Doria looked up, then tapped her scroll with a char stylus. "He may be more safely revived in another three or four hundred years."

"How so? His condition is unchanging as long as he lies in the bath of ice."

"I've been looking at the records of revivals since the earliest times and compiling figures. We Tempori

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...