- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

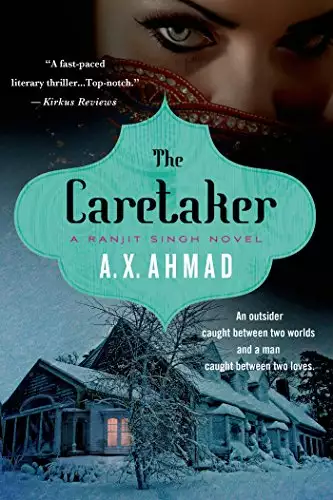

A gripping, evocative thriller about a disgraced Sikh Indian Army captain who works as the caretaker for a U.S. Senator's Martha's Vineyard estate, and becomes ensnared in the Senator's shadowy world.

Ranjit Singh, a former Indian Army Captain trying to escape a shameful past, now lives on Martha's Vineyard, and works as a caretaker for the vacation homes of the rich and powerful. One harsh winter, Ranjit needs a place to stay, and illegally moves his family into an empty, luxurious vacation home belonging to an African-American Senator. Ensconced in the house, he tries to forget his brief affair with Anna, the Senator's wife, and focuses on providing for his family. But one night, their idyll is shattered when mysterious armed men break into the house, searching for an antique porcelain doll.

Forced to flee, Ranjit is hunted by unknown forces, and becomes drawn into the Senator's shadowy world. To save his family and solve the mystery of the doll, he must join forces with Anna, who has her own dark secrets. As he battles to save his family, Ranjit's painful past resurfaces, and he must finally confront the hidden event that destroyed his Army career—and forced him to leave India.

Tightly plotted, action-packed, smart and surprisingly moving, A. X. Ahmad's The Caretaker takes us from the desperate world of migrant workers to the elite African-American community of Martha's Vineyard, and a secret high-altitude war between India and Pakistan.

A Macmillan Audio production.

Release date: May 21, 2013

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Caretaker

A.X. Ahmad

The Senator's wife is late. Very late.

Ranjit Singh stands beside his battered Ford truck and squints down the long, empty line of Beach Road. There is no sign of Anna Neals's silver Mercedes. Only seagulls coast through the evening sky, their shrieks drowned out by the waves crashing across the road.

He turns and looks at the gray-shingled liquor store behind him, wondering how much longer it will be open. It is mid-December, and shops close early during the off-season on Martha's Vineyard. If he loiters in the empty parking lot, the Edgartown cops will surely notice him, and that's the last thing he wants.

If anybody else were an hour late, he would have left. But Anna Neals isn't just anybody, she is the wife of Clayton Neals, the longest-serving African-American senator. He has worked for her all summer, trimming hedges and building stone steps down to her private beach. When she called this morning, he heard her warm, melodious voice and instantly agreed to meet her.

But she is now an hour and ten minutes late. Damn it.

Ranjit leans against the green flatbed truck, feeling the warm metal against his aching back. Though the gold cursive painted on the door says SINGH LANDSCAPE COMPANY, he's the only employee, and his six-foot frame has been bent over all day, raking piles of red and yellow leaves. Before driving over to meet Anna, he changed into a red turban and his cleanest army surplus sweater—the epaulettes torn off—and even tried to clean his cracked fingernails, then gave up. The long summer of landscaping has seamed them with dirt.

A car speeds down Beach Road and feathers into the parking lot, but it isn't hers, it's a rust-eaten blue Mercury, its front bumper held on with duct tape. In the backseat, caged in by a mesh partition, is a thick-muscled black dog wearing a black leather collar.

The car screeches to a halt and a heavyset man in a red plaid shirt emerges from the passenger seat, mumbling something to the driver. Plaid-shirt walks toward the liquor store with a rolling gait, like a sailor unused to dry land.

Hunters, probably on a day trip from the Cape. Ranjit looks down at his watch: five minutes, no more; as it is, he is late picking up his daughter from her school.

He stares across the road at the cold, angry ocean. When he first came to the island with his wife and daughter six months ago, the water was warm and shimmering, the beaches were lined with parked cars, and long-tailed kites fluttered in the hot sky. All summer and into the fall he'd worked as a landscaper, feeling his unused muscles stretch and harden, feeling the hot sun beat down on him, and felt a kind of peace.

But now winter is upon them and the tourists are all gone. The ice-cream parlors and clam shacks have closed, and the migrant workers—the Jamaicans and Bulgarians and Czechs—have left. Even the sky feels like a gray bowl jammed over the island.

Worse, all the landscaping jobs have ended. For the millionth time Ranjit wonders how he is going to survive the winter months. Food and gas here are so expensive, and lately, the furnace in their old house has been cutting out abruptly. If it dies, he just won't have the money to get it fixed.

He needs to find another job soon, or else he'll have to return to Boston and work in Lallu Singh's cramped, overheated Indian store, and the thought of going back there makes him sick.

An hour and a quarter late. The Senator's dark-eyed wife definitely isn't coming, and hope fades away, replaced by a deep disappointment. Forget it.

He strides toward the liquor store for a nip of Bacardi to dull his mind before heading out. At the doorway he slows down, and can't help looking over his shoulder one last time.

Someone slams right into him.

The man in the plaid shirt staggers and clutches a case of beer to his chest. A tall bottle of bourbon balanced on top of it falls and hits the asphalt with a crack. Its neck shears off and it rolls away slowly, the golden liquor glugging out.

The dog in the back of the car barks once, a sound from deep within its chest.

"Aww, crap. Look what you've done." Plaid-shirt's voice is slurred with alcohol. Despite his thick stubble, he has the face of a spoiled child, his high forehead framed by long, uncombed blond hair. "That was a thirty-dollar bottle of Jack."

Ranjit stands motionless. "I'm sorry, sir, but you walked into me."

The man stares at him out of blue, blameless eyes, taking in his red turban, his mustache and full beard.

"Hey, what are you, some kind of Arab?"

"I'm a Sikh from India. Sir, I said I was sorry."

"Sorry, huh? Well, that bottle cost me thirty bucks. Thirty American dollars."

There is no mistaking the menace in the man's voice. There must be no trouble. No trouble and no police. Taking out his wallet, Ranjit counts out a ten and some singles.

"This is all I have."

"This ain't worth shit." Plaid-shirt grabs the bills and turns toward his car. "Hey, you see this bullshit?"

A pale face stares out at Ranjit from the driver's seat, younger, but with the same washed-out blond hair. This man has a blue-black fish tattooed on each forearm.

"I got an idea," the tattooed man says, waving at the broken bottle. "You clean up that mess you made, and we might accept your apology."

His words are followed by the metallic chuck-chuck of a shotgun being racked. A blued barrel appears in the car window, pointed right at Ranjit.

Time stops. As it used to in combat, all noise drains away and the world shrinks to the two men in the empty parking lot. Ranjit is bound to them now by words and actions, bound till something changes.

The tattooed man in the car smiles, showing yellowed teeth. "Come on. Clean it up."

The shotgun doesn't waver. It's a Remington 870 with a twenty-eight-inch hunting barrel, probably loaded with birdshot. At this range the pellets will rip his face to shreds.

There is no choice. Ranjit's hands are shaking with rage as he bends down and reaches for the broken glass. Under his breath he mutters a prayer.

The truly enlightened ones

Are those who neither incite fear in others

Nor fear anyone themselves …

Glass shards are everywhere, glinting in the fading light, and the sharp smell of alcohol stings his nostrils.

The tattooed man in the car watches him, finger tensed on the shotgun trigger. The dog caged in the backseat paces and growls. Plaid-shirt places the carton of beer on the hood of the car and leans back unsteadily, lighting up a cigarette.

A sliver of broken glass slices into the ball of Ranjit's thumb. He gasps as warm blood puddles into the palm of his hand.

Plaid-shirt chuckles. "Aww, look at him. He's bleeding."

The tattooed man in the car joins in the laughter, the shotgun barrel wobbling with hilarity.

Ranjit's neck burns with shame.

The truly enlightened ones

Are those …

"Come on, towel-head. My beer's getting warm."

Fuck it. Ranjit reaches for the jagged neck of the bottle, calculating his moves. The dog is caged in, not a threat. Go for the man, grab the shotgun barrel and twist it aside. Jam the jagged glass into his throat, hear him burble and beg.

He straightens up, the glint of glass in his hand. There is a sudden screech of tires and a car door slams like a rifle shot.

"What the hell is going on here? Ranjit, are you okay?"

Anna Neals's silver Mercedes is parked askew. She takes long strides toward them, her boots thudding angrily against the asphalt. Her dark face is hidden behind blank aviator shades, her straightened, jaw-length hair fluttering in the breeze. She's wearing jeans torn at the knees, a silver down jacket, and thick glass bracelets that clank as she walks.

She is shouting now. "Jeff? Norman? Is there a problem here?"

The two hunters' faces redden. The shotgun disappears from the window, but the dog barks loudly and flings himself at the door.

Anna doesn't flinch. "Control that dog. I said, do we have a problem here?"

"No problem, Mrs. Neals. No problem at all." Plaid-shirt picks up his case of beer and ducks around the side of the car. "Hey, your husband is a hero. Stood up to those damn Koreans. Showed 'em."

"I'll pass on your compliments. Now leave before I turn you in for hunting illegally. Open season for waterfowl is over."

Nodding his head, Plaid-shirt stumbles into the car. The dog's nose is pressed against the rear windshield as the car squeals out of the lot, accelerates down Beach Road, and disappears in a blue haze of exhaust.

The only sounds are the crashing of the waves and Anna's angry breathing.

Standing up, Ranjit squeezes the pressure point below his thumb to stop the bleeding. He doesn't want the Senator's wife to make a fuss.

"Anna, it was my fault. I bumped into that man, I was helping him clean up…"

"I know those two, they're real losers. You don't have to put up with their crap. This is America."

He presses the base of his thumb. People are always saying to him, "This is America." What the hell does it mean?

"Please, I'm okay. These things happen. People see my turban…"

But the truth is that he had been unprepared. During his two years in Boston he'd been taunted in Southie, almost beaten up in the North End—but on the Vineyard things have been different. Blacks and whites mingle easily here, and a brown man in a turban is smiled at, a sign of the island's easy tolerance.

Anna is shivering, from the cold or from anger, he can't tell.

"Those morons and their pit bull. Let me see that cut."

"It's nothing."

Ignoring him, she grabs his wrist, pushes her shades onto her head, and holds his thumb up to the light. She's almost his height, striking-looking rather than beautiful, her short, boyish haircut emphasizing her long neck and high cheekbones. It is her eyes that draw him in, black as night, so dark that her stare can be disconcerting. Today the skin around them is puffy, and he realizes, with a shock, that she has been crying.

"You won't need any stitches. It's a clean cut."

She pulls a white cotton handkerchief from her pocket, tears off a strip with her teeth, and bandages his thumb, the wrapping tight and professional. Noticing his appraising look, she smiles, and deep dimples appear in her cheeks.

"Surprised? I used to go hunting with my father. He'd get hurt, and I'd bandage him up. I've had a lot of practice fixing up men."

When she's done, the bandage is wrapped so tightly that his thumb throbs like a drumbeat.

A cold wind blows in from the ocean and she shivers and hugs herself. "Ranjit, I'm sorry I'm so late. I didn't think you'd still be here."

He remains silent, waiting for her explanation.

"Clayton arrived this afternoon. Unannounced."

"The Senator's here? But I saw him on television just last night, he was at a press conference in Washington—"

"Yeah, well," Anna says, "he flew in from D.C. a few hours ago. He said he'd had enough of the press."

She stands in front of him like a hurt child, hugging herself tightly. He wants to lean forward and wrap his arms around her. Instead, he doesn't move an inch.

"Anna, why did you want to see me?"

She takes a deep breath. "Look, I wanted to say that I'm really sorry. I owe you an explanation for my behavior that day. I was really upset, and believe it or not, you helped me. But…"

He feels the sharp disappointment again. "It's all right. I understand."

"You do? You're kind to say that." There is a silence and then she continues, her tone brisker. "Listen, I was thinking. Are you still staying here through the winter? Or are you heading back to Boston?"

"I'd like to stay here. I hated it in Boston."

"Well, I talked to Clayton, and we need a caretaker for the house. Our regular guy just broke his leg. You can start now, and we'll pay you through next spring. What do you think?"

She smiles and removes a strand of hair that has blown into the corner of her mouth.

He is stunned. It's impossible to get a job as a caretaker on the island; only old, trusted Vineyarders get to take care of rich people's houses. And a steady paycheck means that he can stay here through the winter, maybe even move to a house where the heating actually works.

"It's not a lot of work. Close up the house, shovel snow, check for leaks. What do you say?"

He nods slowly. "Okay, Anna—thank you. I'll take the job."

She jingles car keys in her coat pocket and looks away. "Go see Clayton tonight, he'll fill you in. I better get going. I'm catching the evening ferry to the mainland."

"You're leaving?"

"I need a change of scene. The last few months have been so … taxing. But I'm not going far, just to the house in Boston."

There seems to be nothing else to say. They turn and walk to Anna's car, its engine still purring, the soft wail of jazz coming from inside. Ranjit knows that the silver Mercedes Kompressor costs more money than he has earned during his two and a half years in America.

She stops, a hand on the door handle. "You're sure you want to stay here? It's brutal in the winter. I lived here off-season as a child, almost went mad with boredom."

He nods. "I'll be all right. I'm used to the cold."

"I thought India was hot? Tropical?"

"No. We have mountains too, high ones. With snow and ice."

She smiles apologetically, and her cheeks curve into dimples again. "I should have known that. Us dumb Americans, huh?"

She puts a hand on his arm, a touch so soft that it's barely there. She gets into the Mercedes, slams the door, and swings the car out onto the road. The powerful engine growls, and she's gone.

The pink neon sign in the liquor store window suddenly blinks out. An elderly man emerges from the store and begins to chain the front doors together.

Ranjit kicks the glass shards aside and hurriedly climbs into his truck. What had he expected from the likes of Anna Neals? She is a senator's wife, and he is just another servant here. Things might have been different if … but there's no point in thinking like that.

The adrenaline rush has subsided. He feels cold and nauseous, and blasts the heater before leaning back and closing his eyes. If Anna had arrived a few minutes later, he would have killed that man. He imagines sharp glass entering the man's soft throat, the screams of a butchered animal …

Taking a deep breath, he remembers what the doctors back home had said: The instincts are there, they don't go away. Anything can trigger them: a loud sound, a movement in the periphery, a threatening shadow. The key is to not follow through, to short-circuit the impulse.

Like the doctors taught him, he breathes deeply and imagines a calm, peaceful place. An image of the Golden Temple at Amritsar gradually takes shape: it sits in the center of the sacred lake, its golden dome burnished by fading sunlight, and from within it he can hear the sound of kirtans being sung.

He is a boy again, following his mother down the long causeway leading to it, the marble warm under their bare feet. It is his father's death anniversary, and they have come to the temple to pray. Underneath the threadbare dupatta that covers her head, Mataji's face is pale, exhausted from crying all day, but she grows calm as she sings the evening prayers. The words float in the air, old and comforting.

A faint, putrid smell tickles his nostrils, disturbing the image. He tries to ignore it, but it grows stronger, and when his eyes flicker open, there is a shimmer in the seat next to him. No doubt it is a trick of the fading light; closing his eyes again, he tries to return to the place of stillness.

There is the sudden, rasping sound of breathing. Those bastards are back. His eyes fly open, and he reaches under his seat for a spanner, then stops abruptly.

Sergeant Khandelkar is sitting in the seat next to him, wearing a white snowsuit, an assault rifle lying across his knees. He is bent over and coughing desperately, his eyes strained and watering.

No, please, Guru, no. It must be a hallucination, triggered by the encounter with the two men. It will go away soon, he will wake up.

The Sergeant's head is shaved to reveal his bony skull, giving him the severe look of a priest. As he wheezes, desperately trying to breathe, Ranjit smells again the putrid smell of decay. Perhaps it's a seizure, they say that people smell things right before their convulsions, almonds or perfume.

The Sergeant manages to take a deep breath. "What is this place, Captain?" His voice is raspy, as though he isn't used to talking anymore.

Ranjit cannot answer. The doctors said this could happen and had given him a bottle of blue pills, but he'd thrown them away before he left India.

"Not much in the way of cover here, is there? We'll have to call for air support." Sergeant Khandelkar shivers, and his face and hands are blue with cold.

Ranjit finds his voice. "Sergeant, is it really you?"

Khandelkar ignores the question. He flexes his bony fingers and stares down at them. "Those men, Captain. You could have easily taken them. Why didn't you?"

"I don't … I don't fight anymore."

Khandelkar laughs. "I see, Captain. You don't fight."

"I'm not a captain. I'm nothing here. Everything has changed."

"Nothing changes. Nothing changes, where I am." Khandelkar's hands are lilac, the color that comes before frostbite. "The cold burns like fire, Captain, did you know that?"

"Khandelkar, I'm sorry, so sorry—" Ranjit reaches out to touch the Sergeant, and finds himself reaching through the air.

The seat next to him is empty. Heat gushes out of the vents in the dashboard, and the air smells like burning leaves.

"Sergeant, where are you?"

In the silence Ranjit can hear the pounding of the waves across the road. He rolls down his window and feels the cold air buffet his face.

Something is ringing. He fumbles in the pocket of his stained canvas coat and finds his cell phone.

"Papaji, where are you? I've been waiting and waiting. My teacher is going home." It's Shanti's nine-year-old voice, rolling her Rs like an American.

"Beti, I'm sorry, I got tied up. Put on your coat and wait in the lobby, okay?"

The truck engine rumbles into life, and he drives quickly down Beach Road, the ocean a dark blur to his right. After a few turns, he reaches Tradewinds Road and arrives at the long beige building of the Oak Bluffs elementary school. Shanti is sitting in the brightly lit lobby, twirling the ends of her long, curly black hair with one hand. Her high forehead and liquid brown eyes are carbon copies of her mother's, but she has his tall, lanky build.

She sees the truck and comes running out, her hair flying behind her. When she opens the door, Ranjit is staring at the empty seat next to him.

"Hello, Papaji. What happened to your thumb?" She reaches out and holds his hand, staring at the knotted strip of cotton.

He pulls his hand away, his breathing quick and shallow.

"What's wrong? Papaji, are you all right?"

Ranjit cannot speak. He holds out his arms and hugs her, feeling her long, skinny body, her breath warm against his cheek.

"I'm fine," he says, pulling away. "I cut my thumb while working. I'm just glad to see you, that's all."

"Can we drive along the ocean? I want to see if the ferry is in. And if the Flying Horses is open."

He's told her a hundred times that the Flying Horses Carousel will be closed till the next summer, but she always insists on checking. It will take him out of his way, but he hates to disappoint her.

Sighing, he turns back toward the ocean.

* * *

He is silent as they drive away. All these years he has feared this would happen. He tries to remember the name of the pale blue pills but cannot.

"Papaji, are you listening to me?"

"Sorry, beti, what were you saying?"

Shanti sighs dramatically. "You need to listen. This girl in my grade, Elena, she's Portuguese, she said that all Indians are short. I said no way, you should see my dad, and she said you just look tall because you wear a turban, and I said, my dad is tall even without a turban, but she wouldn't believe me, can you believe it?"

"Beti, Americans have strange ideas about us."

"Not all of them. Just some. And, oh, Miss Heather said to ask you if we're staying for the winter. She said that all the foreign kids start school in the fall but then they leave, and she never gets the textbooks back. Are we going back to Boston?"

"We're staying."

"Hector's gone back to Brazil. And Jorge."

He thinks of the two miserable years in Boston, slaving in the basement of Lallu's Indian store. "We're staying, beti. Tell your teacher we're not going anywhere."

"Okay, good, I like it here. Hey, I know the capitals of all fifty states. Let's play, okay? Easy one first. What's the capital of New York?"

As the truck turns onto Seaview Avenue, the sick panic in Ranjit's stomach begins to fade.

"New York City, obviously."

"No, silly, it's Albany. Now, California?"

"San Francisco?"

Shanti peals with laughter. "It's Sacramento! Everybody knows that!"

"It makes no sense. They always choose someplace that no one has heard of. In India, the biggest city is the capital. Like Mumbai. Or Chennai."

"Papaji, really," Shanti says, dissolving with laughter, and he smiles too; being with her always makes him feel better.

They enter the town of Oak Bluffs and speed past the large green oval of Ocean Park, surrounded by the sprawling bungalows of the African-American elite. They pass the strip of beach nicknamed the Inkwell, and just as the long pier of the ferry terminal appears, Ranjit swerves left into town. The marquee of the Strand movie theater is blank, and the carved wooden horses of the Flying Horses Carousel are motionless, but lights are still on at Jerry's Pizza. Ranjit smells hot cheese and feels a sudden pang of hunger, then remembers that he'd given the last of his money to those two men.

"Hey," Shanti says, "we're pretty late today. I hope Mama isn't mad at us."

Usually Preetam sits at home all day, watching her Hindi movies, and panics if they are even five minutes late. But today she has gone with a neighbor to a sewing circle at the church and shouldn't be back till dinnertime.

"Mama's out, remember? I have to go and talk to Senator Neals for a few minutes. I took you there during the summer—it's the house with all the dolls. He was away, but you met his wife."

"I remember that house. Is he the man who's been on television all the time?"

"Yes, that man. But don't ask him any questions."

"Why?"

"Beti, rich people don't like that. If he asks you any questions, just answer politely."

"I'm always polite, Papaji. You know that."

He nods absentmindedly. They drive through the town and stop at the drawbridge leading to Vineyard Haven. A red light flashes and the middle section of the bridge lifts up to let a yacht into the lagoon. He switches off the engine to save gas, an old habit from India.

He is startled at how much information Shanti soaks up, but Preetam always has the television on, and Neals has been on the news for the last two nights.

The news stations replayed the same footage over and over again, showing the Senator walking briskly up the steps of the floodlit Capitol. Despite his sixty-plus years of age, he had the quick grace of a much younger man, and his dark blue suit only emphasized his barrel chest and wide shoulders. His shaved head and flattened nose—at some point it had been broken and roughly set—only added to his aura of authority.

Reaching the top of the stairs, the Senator made a speech about freedom and democracy, and then handed over the microphone to a young Korean-American woman journalist. Still pale from her months in North Korean captivity, the woman described in a shaking voice her arrest on a trumped-up charge of spying, and her subsequent death sentence. If the Senator hadn't flown to Pyongyang to negotiate on her behalf, her body would now be arriving home in a plywood box. As soon as she was done, the reporters surged forward, shouting out questions, but the Senator just raised her arm in a victory salute and then escorted her away.

The news stations all called the Senator a hero, and there was even talk of him running for President someday. Earlier that summer, the same news stations had broadcast programs on the Senator's fading popularity and predicted that he wouldn't be reelected. Thinking about it, Ranjit shakes his head. Opinions change so fast in this country.

The large yacht slides under the raised drawbridge, only the top of its masts visible. Soon the bridge is lowered, and they clatter across it, skirting the town of Vineyard Haven.

The island of Martha's Vineyard is small—roughly triangular, twenty miles from east to west, and ten from north to south—but it houses many worlds. The WASPS live amid their white picket fences in Edgartown, while Oak Bluffs is the home of the African-American elite, whose bungalows cluster around Ocean Park. Vineyard Haven, with its wide harbor and bustling main street, is the commercial heart of the island. Senator Neals has chosen to live far away, among the movie stars and tycoons of Aquinnah, his custom-designed house perched high on its red clay cliffs.

They drive down State Road, past the scattered restaurants and boutiques that cater to the summer people. Jenni Bick's handmade journal store is closed, as is the Vineyard Glassworks, and there are only a handful of cars parked outside Kronig's grocery store. As the population of the island shrinks from a summer high of a hundred thousand down to fifteen thousand, the Vineyard once again becomes a small town.

The twilight gathers around them and Ranjit flicks on his headlights, illuminating stone boundary walls. Hidden behind these are the summer estates of the millionaires, only their driveways and NO TRESPASSING signs visible from the road; the houses are set far back, facing the water. They're empty now, inhabited only by mice and the blinking lights of alarm systems. If this were India, poor people would cut the power to the alarms and move in, shit in the Jacuzzis, keep goats and chickens in the empty swimming pools. But this is not India, this is the Vineyard, and all these beautiful, perfect houses lie empty for most of the year.

He drives through the exclusive towns of West Tisbury and Chilmark, and soon the road becomes a causeway, cutting between the dark waters of Menemsha and Squibnocket ponds. Reaching Lighthouse Road, they drive along the edge of the island, the jagged cliffs falling away to the ocean below.

Ranjit turns into a graveled driveway that curves down the hillside, and the truck whines around the sharp turns. After one last dizzying twist the road flattens out, and there, beyond the Senator's house, is the ink-black ocean, ranks of whitecapped waves racing to the open horizon.

He turns off the engine and the air is filled with the roar of water. Shanti sits silently, mesmerized by the view.

"Beti," he says, "do you know what ocean that is?"

"The Atlantic Ocean."

"And what's on the other side?"

"India."

"How come India? Not Europe?"

Shanti shakes her head firmly. "No, it's India. That's what Mama says."

"What do you remember about India, beti?"

She takes a deep breath. "We were rich in India and we had a big house and mango trees and many servants."

He nods slowly. Just as he thought: she doesn't remember a thing about India, and now Preetam is filling her head with nonsense.

"Wait in the truck. I have to talk to the Senator."

Crunching over the gravel, he approaches the house, praying under his breath. Please, Guru, please let me get this job.

From this level, the house looks deceptively like a modest one-story, its rough fieldstone walls topped by a wide, overhanging roof. The rest of it is hidden on the other side, two lower floors of steel and glass cut into the hillside, ending in a terraced garden with a kidney-shaped swimming pool.

The doorbell chimes deep within the house, but there are no answering footsteps. Despite the chill, perhaps Senator Neals is out on the rear deck, where the sound of the doorbell will be drowned out by the waves.

Shanti presses her nose against the truck window as he walks toward the high hedges that shield the back of the house. He spent hours during the summer trimming them into perfect cubes, but scraggly branches have broken through, undoing all his hard work.

Pushing through a gap in the hedges, he looks at the rear of the house, its rows of tall windows dark and silent. He takes one step forward.

And almost falls over Senator Neals.

Copyright © 2013 by Amin Ahmad

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...